Math Is Fun Forum

You are not logged in.

- Topics: Active | Unanswered

#1851 2026-01-19 21:46:13

- Jai Ganesh

- Administrator

- Registered: 2005-06-28

- Posts: 52,966

Re: crème de la crème

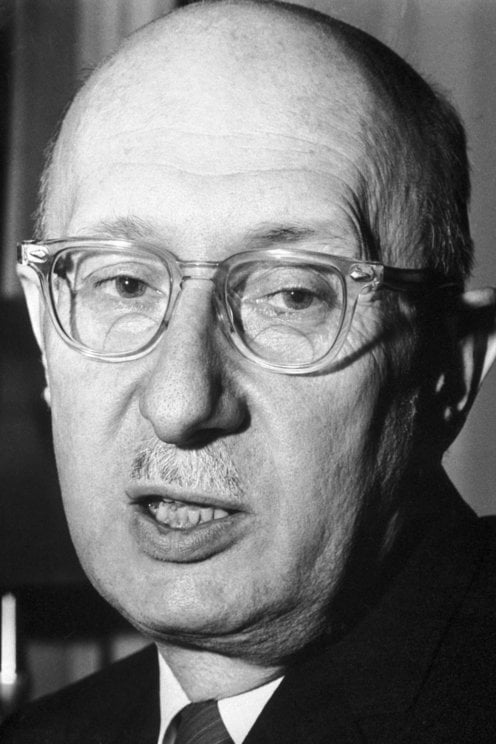

2414) Rudolf Mössbauer

Gist:

Work

According to the principles of quantum physics, the atomic nucleus and surrounding electrons can have only fixed energy levels. When there are transitions among energy levels in the atomic nucleus, high-energy photons known as gamma rays are emitted and absorbed. In a gas a recoil effect occurs when an atom emits a photon. In 1958 Rudolf Mössbauer discovered that the recoil can be eliminated if the atoms are embedded in a crystal structure. This opened up opportunities to study energy levels in atomic nuclei and how these are affected by their surroundings and various phenomena.

Summary

Rudolf Ludwig Mössbauer (born January 31, 1929, Munich, Germany—died September 14, 2011, Grünwald) was a German physicist and winner, with Robert Hofstadter of the United States, of the Nobel Prize for Physics in 1961 for his discovery of the Mössbauer effect.

Mössbauer discovered the effect in 1957, one year before he received his doctorate from the Technical University in Munich. Under normal conditions, atomic nuclei recoil when they emit gamma rays, and the wavelength of the emission varies with the amount of recoil. Mössbauer found that at a low temperature a nucleus can be embedded in a crystal lattice that absorbs its recoil. The discovery of the Mössbauer effect made it possible to produce gamma rays at specific wavelengths, and this proved a useful tool because of the highly precise measurements it allowed. The sharply defined gamma rays of the Mössbauer effect have been used to verify Albert Einstein’s general theory of relativity and to measure the magnetic fields of atomic nuclei.

Mössbauer became professor of physics at the California Institute of Technology, Pasadena, in 1961. Three years later he returned to Munich to become professor of physics at the Technical University, where he retired as professor emeritus in 1997.

Details

Rudolf Ludwig Mössbauer (31 January 1929 – 14 September 2011) was a German physicist who shared the 1961 Nobel Prize in Physics with Robert Hofstadter for his discovery of the Mössbauer effect, which is the basis for Mössbauer spectroscopy.

Career

Mössbauer was born in Munich, where he also studied physics at the Technical University of Munich. He prepared his Diplom thesis in the Laboratory of Applied Physics of Heinz Maier-Leibnitz and graduated in 1955. He then went to the Max Planck Institute for Medical Research in Heidelberg. Since this institute, not part of a university, had no right to award a doctorate, Mössbauer remained under the auspices of Maier-Leibnitz, his official thesis advisor, when he passed his PhD exam in Munich in 1958.

In his PhD, he discovered the recoilless nuclear fluorescence of gamma rays in 191 iridium, the Mössbauer effect. His fame grew immensely in 1960 when Robert Pound and Glen Rebka used this effect to prove the red shift of gamma radiation in the gravitational field of the Earth; this Pound–Rebka experiment was one of the first experimental precision tests of Albert Einstein's general theory of relativity. However, the long-term importance of the Mössbauer effect is its use in Mössbauer spectroscopy. Along with Robert Hofstadter, Rudolf Mössbauer was awarded the 1961 Nobel Prize in Physics.

On the suggestion of Richard Feynman, Mössbauer was invited in 1960 to Caltech in the USA, where he advanced rapidly from research fellow to senior research fellow; he was appointed a full professor of physics in early 1962. In 1964, his alma mater, the Technical University of Munich (TUM), convinced him to go back as a full professor. He retained this position until he became professor emeritus in 1997. As a condition for his return, the faculty of physics introduced a "department" system. This system, strongly influenced by Mössbauer's American experience, was in radical contrast to the traditional, hierarchical "faculty" system of German universities, and it gave the TUM an eminent position in German physics.

In 1972, Rudolf Mössbauer went to Grenoble to succeed Heinz Maier-Leibnitz as the director of the Institut Laue-Langevin just when its newly built high-flux research reactor went into operation. After serving a five-year term, Mössbauer returned to Munich, where he found his institutional reforms reversed by overarching legislation. Until the end of his career, he often expressed bitterness over this "destruction of the department." Meanwhile, his research interests shifted to neutrino physics.

Mössbauer was regarded as an excellent teacher. He gave highly specialized lectures on numerous courses, including Neutrino Physics, Neutrino Oscillations, The Unification of the Electromagnetic and Weak Interactions and The Interaction of Photons and Neutrons With Matter. In 1984, he gave undergraduate lectures to 350 people taking the physics course. He told his students: “Explain it! The most important thing is that you can explain it! You will have exams, there you have to explain it. Eventually, you pass them, you get your diploma and you think, that's it! – No, the whole life is an exam, you'll have to write applications, you'll have to discuss with peers... So learn to explain it! You can train this by explaining to another student, a colleague. If they are not available, explain it to your mother – or to your cat!”

Personal life

Mössbauer married Elizabeth Pritz in 1957. They had a son, Peter and two daughters Regine and Susi. They divorced in 1983, and he married his second wife Christel Braun in 1985.

Mössbauer died at Grünwald, Germany on 14 September 2011 at 82.

It appears to me that if one wants to make progress in mathematics, one should study the masters and not the pupils. - Niels Henrik Abel.

Nothing is better than reading and gaining more and more knowledge - Stephen William Hawking.

Offline

#1852 2026-01-20 16:56:02

- Jai Ganesh

- Administrator

- Registered: 2005-06-28

- Posts: 52,966

Re: crème de la crème

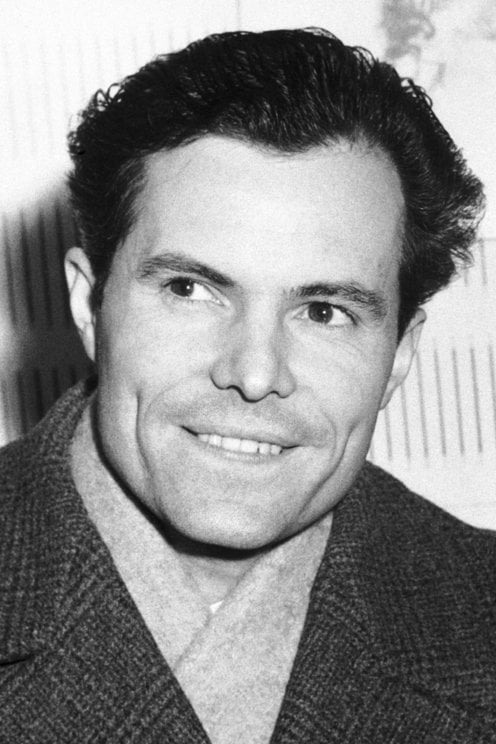

2415) Melvin Calvin

Gist:

Work

One of the most fundamental processes of life is photosynthesis. Green plants use energy from sunlight to make carbohydrates out of water and carbon dioxide in the air. Through studies during the early 1950s, particularly of single-cell green algae, Melvin Calvin and his colleagues traced the path taken by carbon through different stages of photosynthesis. For this they made use of tools such as radioactive isotopes and chromatography. Their findings included insight into the important role played by phosphorous compounds during the composition of carbohydrates.

Summary

Melvin Ellis Calvin (April 8, 1911 – January 8, 1997) was an American biochemist known for discovering the Calvin cycle along with Andrew Benson and James Bassham, for which he was awarded the 1961 Nobel Prize in Chemistry. He spent most of his five-decade career at the University of California, Berkeley.

Early life and education

Melvin Calvin was born in St. Paul, Minnesota, the son of Elias Calvin and Rose Herwitz, Jewish immigrants from the Russian Empire (now known as Lithuania and Georgia).

At an early age, Melvin Calvin’s family moved to Detroit, Michigan where his parents ran a grocery store to earn their living. Melvin Calvin was often found exploring his curiosity by looking through all of the products that made up their shelves.

After he graduated from Central High School in 1928, he went on to study at Michigan College of Mining and Technology (now known as Michigan Technological University) where he received the school’s first Bachelors of Science in Chemistry. He went on to earn his PhD at the University of Minnesota in 1935. While under the mentorship of George Glocker, he studied and wrote his thesis on the electron affinity of halogens. He was invited to join the lab of Michael Polanyi as a Post Doctoral student at the University of Manchester. The two years he spent at the lab were focused on studying the structure and behavior of organic molecules. In 1942, He married Marie Genevieve Jemtegaard, and they had three daughters, Elin, Sowie, and Karole, and a son, Noel.

Career

On a visit to the University of Manchester, Joel Hildebrand, the director of UC Radiation Laboratory, invited Calvin to join the faculty at the University of California, Berkeley. This made him the first non-Berkeley graduate hired by the chemistry department in +25 years. He invited Calvin to push forward in radioactive carbon research because "now was the time". Calvin's original research at UC Berkeley was based on the discoveries of Martin Kamen and Sam Ruben in long-lived radioactive carbon-14 in 1940.

In 1947, he was promoted to a Professor of Chemistry and the director of the Bio-Organic Chemistry group in the Lawrence Radiation Laboratory. The team he formed included: Andrew Benson, James A. Bassham, and several others. Andrew Benson was tasked with setting up the photosynthesis laboratory. The purpose of this lab was to discover the path of carbon fixation through the process of photosynthesis. The greatest impact of the research was discovering the way that light energy converts into chemical energy. Using the carbon-14 isotope as a tracer, Calvin, Andrew Benson and James Bassham mapped the complete route that carbon travels through a plant during photosynthesis, starting from its absorption as atmospheric carbon dioxide to its conversion into carbohydrates and other organic compounds. The process is part of the photosynthesis cycle. It was given the name the Calvin–Benson–Bassham Cycle, named for the work of Melvin Calvin, Andrew Benson, and James Bassham. There were many people who contributed to this discovery but ultimately Melvin Calvin led the charge.

In 1963, Calvin was given the additional title of Professor of Molecular Biology. He was founder and Director of the Laboratory of Chemical Biodynamics, known as the “Roundhouse”, and simultaneously Associate Director of Berkeley Radiation Laboratory, where he conducted much of his research until his retirement in 1980. In his final years of active research, he studied the use of oil-producing plants as renewable sources of energy. He also spent many years testing the chemical evolution of life and wrote a book on the subject that was published in 1969.

Details

Melvin Calvin (born April 8, 1911, St. Paul, Minnesota, U.S.—died January 8, 1997, Berkeley, California) was an American biochemist who received the 1961 Nobel Prize for Chemistry for his discovery of the chemical pathways of photosynthesis.

Calvin was the son of immigrant parents. His father was from Kalvaria, Lithuania, so the Ellis Island immigration authorities renamed him Calvin; his mother was from Russian Georgia. Soon after his birth, the family moved to Detroit, Michigan, where Calvin showed an early interest in science, especially chemistry and physics. In 1927 he received a full scholarship from the Michigan College of Mining and Technology (now Michigan Technological University) in Houghton, where he was the school’s first chemistry major. Few chemistry courses were offered, so he enrolled in mineralogy, geology, paleontology, and civil engineering courses, all of which proved useful in his later interdisciplinary scientific research. Following his sophomore year, he interrupted his studies for a year, earning money as an analyst in a brass factory.

Calvin earned a bachelor’s degree in 1931, and then he attended the University of Minnesota in Minneapolis, from which he received a doctorate in 1935 with a dissertation on the electron affinity of halogen atoms. With a Rockefeller Foundation grant, he researched coordination catalysis, activation of molecular hydrogen, and metalloporphyrins (porphyrin and metal compounds) at the University of Manchester in England with Michael Polanyi, who introduced him to the interdisciplinary approach. In 1937 Calvin joined the faculty of the University of California, Berkeley, as an instructor. (He was the first chemist trained elsewhere to be hired by the school since 1912.) He rose through the ranks to become director (1946) of the bioorganic chemistry group at the school’s Lawrence Radiation Laboratory (now the Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory), director of the Laboratory of Chemical Biodynamics (1963), associate director of Lawrence Livermore (1967), and University Professor of Chemistry (1971).

At Berkeley, Calvin continued his work on hydrogen activation and began work on the colour of organic compounds, leading him to study the electronic structure of organic molecules. In the early 1940s, he worked on molecular genetics, proposing that hydrogen bonding is involved in the stacking of nucleic acid bases in chromosomes. During World War II, he worked on cobalt complexes that bond reversibly with oxygen to produce an oxygen-generating apparatus for submarines or destroyers. In the Manhattan Project, he employed chelation and solvent extraction to isolate and purify plutonium from other fission products of uranium that had been irradiated. Although not developed in time for wartime use, his technique was later used for laboratory separations.

In 1942 Calvin married Genevieve Jemtegaard, with later Nobel chemistry laureate Glenn T. Seaborg as best man. The married couple collaborated on an interdisciplinary project to investigate the chemical factors in the Rh blood group system. Genevieve was a juvenile probation officer, but, according to Calvin’s autobiography, “she spent a great deal of time actually in the laboratory working with the antigenic material. This was her first chemical laboratory experience but not her last by any means.” Together they helped to determine the structure of one of the Rh antigens, which they named elinin for their daughter Elin. Following the oil embargo after the 1973 Arab-Israeli War, they sought suitable plants, e.g., genus Euphorbia, to convert solar energy to hydrocarbons for fuel, but the project failed to be economically feasible.

In 1946 Calvin began his Nobel prize-winning work on photosynthesis. After adding carbon dioxide with trace amounts of radioactive carbon-14 to an illuminated suspension of the single-cell green alga Chlorella pyrenoidosa, he stopped the alga’s growth at different stages and used paper chromatography to isolate and identify the minute quantities of radioactive compounds. This enabled him to identify most of the chemical reactions in the intermediate steps of photosynthesis—the process in which carbon dioxide is converted into carbohydrates. He discovered the “Calvin cycle,” in which the “dark” photosynthetic reactions are impelled by compounds produced in the “light” reactions that occur on absorption of light by chlorophyll to yield oxygen. Also using isotopic tracer techniques, he followed the path of oxygen in photosynthesis. This was the first use of a carbon-14 tracer to explain a chemical pathway.

Calvin’s research also included work on electronic, photoelectronic, and photochemical behaviour of porphyrins; chemical evolution and organic geochemistry, including organic constituents of lunar rocks for the U.S. National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA); free radical reactions; the effect of deuterium (“heavy hydrogen”) on biochemical reactions; chemical and viral carcinogenesis; artificial photosynthesis (“synthetic chloroplasts”); radiation chemistry; the biochemistry of learning; brain chemistry; philosophy of science; and processes leading to the origin of life.

Calvin’s bioorganic group eventually required more space, so he designed the new Laboratory of Chemical Biodynamics (the “Roundhouse” or “Calvin Carousel”). This circular building contained open laboratories and numerous windows but few walls to encourage the interdisciplinary interaction that he had carried out with his photosynthesis group at the old Radiation Laboratory. He directed this laboratory until his mandatory age retirement in 1980, when it was renamed the Melvin Calvin Laboratory. Although officially retired, he continued to come to his office until 1996 to work with a small research group.

Calvin was the author of more than 600 articles and 7 books, and he was the recipient of several honorary degrees from U.S. and foreign universities. His numerous awards included the Priestley Medal (1978), the American Chemical Society’s highest award, and the U.S. National Medal of Science (1989), the highest U.S. civilian scientific award.

It appears to me that if one wants to make progress in mathematics, one should study the masters and not the pupils. - Niels Henrik Abel.

Nothing is better than reading and gaining more and more knowledge - Stephen William Hawking.

Offline

#1853 2026-01-21 17:11:56

- Jai Ganesh

- Administrator

- Registered: 2005-06-28

- Posts: 52,966

Re: crème de la crème

2416) Georg von Békésy

Gist:

Work

Our hearing works because sound waves from the surrounding world are converted in the ear into vibrations in membranes and bones. These are further converted into electrical impulses that are passed on to the brain, resulting in auditory impressions. In a series of studies from 1940 to the 1960s, Georg von Békésy clarified how processes in the cochlea in the inner ear proceed, in part by studying vibrations in membranes with the help of a microscope and sequences of photographs as well as by measuring variations in electrical charges in the receptors.

Summary

Georg von Békésy (born June 3, 1899, Budapest, Hungary—died June 13, 1972, Honolulu, Hawaii, U.S.) was an American physicist and physiologist who received the 1961 Nobel Prize for Physiology or Medicine for his discovery of the physical means by which sound is analyzed and communicated in the cochlea, a portion of the inner ear.

As director of the Hungarian Telephone System Research Laboratory (1923–46), Békésy worked on problems of long-distance communication and became interested in the mechanics of human hearing. At the telephone laboratory, the University of Budapest (1939–46), the Karolinska Institute, Stockholm (1946–47), and Harvard University (1947–66) he conducted intensive research that led to the construction of two cochlea models and highly sensitive instruments that made it possible to understand the hearing process, differentiate between certain forms of deafness, and select proper treatment more accurately.

Since the mid-19th century, it had been known that the vibratory tissue most important for hearing is the basilar membrane, stretching the length of the snail-shaped cochlea and dividing it into two interior canals. Békésy found that sound travels along the basilar membrane in a series of waves, and he demonstrated that these waves peak at different places on the membrane: low frequencies toward the end of the cochlea and high frequencies near its entrance, or base. He discovered that the location of the nerve receptors and the number of receptors involved are the most important factors in determining pitch and loudness.

Békésy became professor of sensory sciences at the University of Hawaii in 1966. His books include Experiments in Hearing (1960) and Sensory Inhibition (1967).

Details

Georg von Békésy (3 June 1899 – 13 June 1972) was a Hungarian-American biophysicist.

By using strobe photography and silver flakes as a marker, he was able to observe that the basilar membrane moves like a surface wave when stimulated by sound. Because of the structure of the cochlea and the basilar membrane, different frequencies of sound cause the maximum amplitudes of the waves to occur at different places on the basilar membrane along the coil of the cochlea. High frequencies cause more vibration at the base of the cochlea while low frequencies create more vibration at the apex.

He concluded that his observations showed how different sound wave frequencies are locally dispersed before exciting different nerve fibers that lead from the cochlea to the brain.

In 1961, he was awarded the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for his research on the function of the cochlea in the mammalian hearing organ.

Biography

Békésy was born on 3 June 1899 in Budapest, Hungary, as the first of three children (György 1899, Lola 1901 and Miklós 1903) to Sándor Békésy (1860–1923), an economic diplomat, and to his mother Paula Mazaly.

The Békésy family was originally Reformed but converted to Catholicism. His mother, Paula Mazaly (1877–1974) was born in Szagolyca (now Čađavica, Croatia). His maternal grandfather was from Pécs. His father was born in Kolozsvár (now Cluj-Napoca, Romania).

Békésy went to school in Budapest, Munich, and Zürich. He studied chemistry in Bern and received his PhD in physics on the subject: "Fast way of determining molecular weight" from the University of Budapest in 1926.

He then spent one year working in an engineering firm. He published his first paper on the pattern of vibrations of the inner ear in 1928. He was offered a position at Uppsala University by Róbert Bárány, which he declined because of the hard Swedish winters.

Before and during World War II, Békésy worked for the Hungarian Post Office (1923 to 1946), where he did research on telecommunications signal quality. This research led him to become interested in the workings of the ear. In 1946, he left Hungary to follow this line of research at the Karolinska Institute in Sweden.

In 1947, he moved to the United States, working at Harvard University until 1966. In 1962 he was elected a Member of the German Academy of Sciences Leopoldina. After his lab was destroyed by fire in 1965, he was invited to lead a research laboratory of sense organs in Honolulu, Hawaii. He became a professor at the University of Hawaiʻi in 1966 and died in Honolulu.

He became a well-known expert in Asian art. He had a large collection which he donated to the Nobel Foundation in Sweden. His brother, Dr. Miklós Békésy (1903-1980), stayed in Hungary and became a famous agrobiologist who was awarded the Kossuth Prize.

Research

Békésy contributed most notably to our understanding of the mechanism by which sound frequencies are registered in the inner ear. He developed a method for dissecting the inner ear of human cadavers while leaving the cochlea partly intact. By using strobe photography and silver flakes as a marker, he was able to observe that the basilar membrane moves like a surface wave when stimulated by sound. Because of the structure of the cochlea and the basilar membrane, different frequencies of sound cause the maximum amplitudes of the waves to occur at different places on the basilar membrane along the coil of the cochlea. High frequencies cause more vibration at the base of the cochlea while low frequencies create more vibration at the apex.

Békésy concluded from these observations that by exciting different locations on the basilar membrane different sound wave frequencies excite different nerve fibers that lead from the cochlea to the brain. He theorized that, due to its placement along the cochlea, each sensory cell (hair cell) responds maximally to a specific frequency of sound (the so-called tonotopy). Békésy later developed a mechanical model of the cochlea, which confirmed the concept of frequency dispersion by the basilar membrane in the mammalian cochlea.

In an article published posthumously in 1974, Békésy reviewed progress in the field, remarking "In time, I came to the conclusion that the dehydrated cats and the application of Fourier analysis to hearing problems became more and more a handicap for research in hearing," referring to the difficulties in getting animal preparations to behave as when alive, and the misleading common interpretations of Fourier analysis in hearing research.

It appears to me that if one wants to make progress in mathematics, one should study the masters and not the pupils. - Niels Henrik Abel.

Nothing is better than reading and gaining more and more knowledge - Stephen William Hawking.

Offline

#1854 2026-01-22 18:06:17

- Jai Ganesh

- Administrator

- Registered: 2005-06-28

- Posts: 52,966

Re: crème de la crème

2417) Donald Glaser

Gist:

Life

Donald Glaser was born in Cleveland, Ohio to Russian immigrants. His father was a businessman. After first studying at Case School of Applied Science in Cleveland, he later received his PhD in physics from California Institute of Technology, Pasadena, in 1949. He then moved to the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor, where he carried out the research that led to his Nobel Prize, before moving to the University of California, Berkeley, in 1959. Beginning in the 1960s, Glaser devoted himself to molecular biology. He was married twice and had two children from his first marriage.

Work

Our ability to study the smallest components of our world took a giant leap forward when C.T.R. Wilson invented the cloud chamber, where the trails of charged particles can be observed. Donald Glaser's invention of the bubble chamber in 1952 made it possible to study particles with higher energies. When charged particles rush forward through the chamber filled with a liquid at near-boiling point, they ionize atoms they pass by. When the pressure inside the chamber is then reduced, bubbles form around these charged atoms. The particles' tracks can then be photographed and analyzed.

Summary

Donald A. Glaser (born September 21, 1926, Cleveland, Ohio, U.S.—died February 28, 2013, Berkeley, California) was an American physicist and recipient of the 1960 Nobel Prize for Physics for his invention (1952) and development of the bubble chamber, a research instrument used in high-energy physics laboratories to observe the behaviour of subatomic particles.

After graduating from Case Institute of Technology, Cleveland, in 1946, Glaser attended the California Institute of Technology, Pasadena, where he received a Ph.D. in physics and mathematics in 1950. He then began teaching at the University of Michigan, where he became a professor in 1957.

Glaser conducted research with Nobelist Carl Anderson, who was using cloud chambers to study cosmic rays. Glaser, recognizing that cloud chambers had a number of limitations, created a bubble chamber to learn about the pathways of subatomic particles. Because of the relatively high density of the bubble-chamber liquid (as opposed to the vapour that filled cloud chambers), collisions producing rare reactions were more frequent and were observable in finer detail. New collisions could be recorded every few seconds when the chamber was exposed to bursts of high-speed particles from particle accelerators. As a result, physicists were able to discover the existence of a host of new particles, notably quarks. At the age of 34, Glaser became one of the youngest scientists ever to be awarded a Nobel Prize.

In 1959 Glaser joined the staff of the University of California, Berkeley, where he became a professor of physics and molecular biology in 1964. In 1971 he cofounded the Cetus Corp., a biotechnology company that developed interleukin-2 and interferon for cancer therapy. The firm was sold (1991) to Chiron Corp., which was later acquired by Novartis. In the 1980s Glaser turned to the field of neurobiology and conducted experiments on vision and how it is processed by the human brain.

Details

Donald Arthur Glaser (September 21, 1926 – February 28, 2013) was an American physicist and biologist who received the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1960 for his invention of the bubble chamber.

Personal life

Donald Arthur Glaser was born on September 21, 1926, in Cleveland, Ohio, to Russian Jewish immigrants, Lena and William J. Glaser, a businessman. He enjoyed music and played the piano, violin, and viola. He went to Cleveland Heights High School, where he became interested in physics as a means to understand the physical world. He died in his sleep at the age of 86 on February 28, 2013, in Berkeley, California.

Education and career

Glaser attended Case School of Applied Science (now Case Western Reserve University), where he completed his Bachelor of Science degree in physics and mathematics in 1946. During the course of his education there, he became especially interested in particle physics. He played viola in the Cleveland Philharmonic while at Case, and taught mathematics classes at the college after graduation. He continued on to the California Institute of Technology (Caltech), where he pursued his PhD in physics. His interest in particle physics led him to work with Nobel laureate Carl David Anderson, studying cosmic rays with cloud chambers. He preferred the accessibility of cosmic ray research over that of nuclear physics. While at Caltech he learned to design and build the equipment he needed for his experiments, and this skill would prove to be useful throughout his career. He also attended molecular genetics seminars led by Nobel laureate Max Delbrück; he would return to this field later. Glaser completed his doctoral thesis, The Momentum Distribution of Charged Cosmic Ray Particles Near Sea Level, after starting as an instructor at the University of Michigan in 1949. He received his PhD from Caltech in 1950, and he was promoted to professor at Michigan in 1957 He joined the faculty of UC Berkeley in 1959 as a professor of physics. During this time, his research concerned short-lived elementary particles. The bubble chamber enabled him to observe the paths and lifetimes of the particles. Starting in 1962, Glaser changed his field of research to molecular biology, starting with a project on ultraviolet-induced cancer. In 1964, he was given the additional title of professor of molecular biology. Glaser's position (since 1989) was professor of physics and neurobiology in the graduate school.

Bubble chamber

While teaching at Michigan, Glaser began to work on experiments that led to the creation of the bubble chamber. His experience with cloud chambers at Caltech had shown him that they were inadequate for studying elementary particles. In a cloud chamber, particles pass through gas and collide with metal plates that obscure the scientists' view of the event. The cloud chamber also needs time to reset between recording events and cannot keep up with accelerators' rate of particle production.

He experimented with using superheated liquid in a glass chamber. Charged particles would leave a track of bubbles as they passed through the liquid, and their tracks could be photographed. He created the first bubble chamber with ether. He experimented with hydrogen while visiting the University of Chicago, showing that hydrogen would also work in the chamber.

It has often been claimed that Glaser was inspired to his invention by the bubbles in a glass of beer; however, in a 2006 talk, he refuted this story, saying that although beer was not the inspiration for the bubble chamber, he did experiments using beer to fill early prototypes.

His new invention was ideal for use with high-energy accelerators, so Glaser traveled to Brookhaven National Laboratory with some students to study elementary particles using the accelerator there. The images that he created with his bubble chamber brought recognition of the importance of his device, and he was able to get funding to continue experimenting with larger chambers. Glaser was then recruited by Nobel laureate Luis Alvarez, who was working on a hydrogen bubble chamber at the University of California at Berkeley. Glaser accepted an offer to become a professor of physics there in 1959.

Nobel Prize

Glaser was awarded the 1960 Nobel Prize for Physics for the invention of the bubble chamber. His invention allowed scientists to observe what happens to high-energy beams from an accelerator, thus paving the way for many important discoveries.

It appears to me that if one wants to make progress in mathematics, one should study the masters and not the pupils. - Niels Henrik Abel.

Nothing is better than reading and gaining more and more knowledge - Stephen William Hawking.

Offline

#1855 Yesterday 21:06:40

- Jai Ganesh

- Administrator

- Registered: 2005-06-28

- Posts: 52,966

Re: crème de la crème

2418) Willard Libby

Gist:

Work

Carbon is a fundamental component in all living material. In nature there are two variants, or isotopes: carbon-12, which is stable, and carbon-14, which is radioactive. Carbon-14 forms in the atmosphere when acted upon by cosmic radiation and then deteriorates. When an organism dies and the supply of carbon from the atmosphere ceases, the content of carbon-14 declines through radioactive decay at a fixed rate. In 1949 Willard Libby developed a method for applying this to determine the age of fossils and archeological relics.

Summary

Willard Frank Libby (December 17, 1908 – September 8, 1980) was an American physical chemist noted for his role in the 1949 development of radiocarbon dating, a process which revolutionized archaeology and palaeontology. For his contributions to the team that developed this process, Libby was awarded the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 1960.

A 1931 chemistry graduate of the University of California, Berkeley, from which he received his doctorate in 1933, he studied radioactive elements and developed sensitive Geiger counters to measure weak natural and artificial radioactivity. During World War II he worked in the Manhattan Project's Substitute Alloy Materials (SAM) Laboratories at Columbia University, developing the gaseous diffusion process for uranium enrichment.

After the war, Libby accepted a professorship at the University of Chicago's Institute for Nuclear Studies, where he developed the technique for dating organic compounds using carbon-14. He also discovered that tritium similarly could be used for dating water, and therefore wine. In 1950, he became a member of the General Advisory Committee (GAC) of the Atomic Energy Commission (AEC). He was appointed a commissioner in 1954, becoming its sole scientist. He sided with Edward Teller on pursuing a crash program to develop the hydrogen bomb, participated in the Atoms for Peace program, and defended the administration's atmospheric nuclear testing.

Libby resigned from the AEC in 1959 to become professor of chemistry at University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA), a position he held until his retirement in 1976. In 1962, he became the director of the University of California statewide Institute of Geophysics and Planetary Physics (IGPP). He started the first Environmental Engineering program at UCLA in 1972, and as a member of the California Air Resources Board, he worked to develop and improve California's air pollution standards.

Details

Willard Frank Libby (born Dec. 17, 1908, Grand Valley, Colo., U.S.—died Sept. 8, 1980, Los Angeles, Calif.) was an American chemist whose technique of carbon-14 (or radiocarbon) dating provided an extremely valuable tool for archaeologists, anthropologists, and earth scientists. For this development he was honoured with the Nobel Prize for Chemistry in 1960.

Libby, the son of farmer Ora Edward Libby and his wife, Eva May (née Rivers), attended the University of California at Berkeley, where he received a bachelor’s degree (1931) and a doctorate (1933). After graduation, he joined the faculty at Berkeley, where he rose through the ranks from instructor (1933) to assistant professor (1938) to associate professor (1945). In 1940 he married Leonor Hickey, by whom he had twin daughters. In 1966 he was divorced and married Leona Woods Marshall, a staff member at the RAND Corporation of Santa Monica, Calif.

In 1941 Libby received a Guggenheim fellowship to work at Princeton University in New Jersey, but his work was interrupted by the entry of the United States into World War II. He was sent on leave to the Columbia War Research Division of Columbia University in New York City, where he worked with Nobel chemistry laureate Harold C. Urey until 1945. Libby became professor of chemistry at the Institute for Nuclear Studies (now the Enrico Fermi Institute for Nuclear Studies) and the department of chemistry at the University of Chicago (1945–59). He was appointed by Pres. Dwight D. Eisenhower to the U.S. Atomic Energy Commission (1955–59). From 1959 Libby was a professor of chemistry at the University of California, Los Angeles, and director of its Institute of Geophysics and Planetary Physics (from 1962) until his death. He was the recipient of numerous honours, awards, and honourary degrees.

During the late 1950s, Libby and physicist Edward Teller, both committed to the Cold War and both prominent advocates of nuclear weapons testing, opposed Nobel chemistry and peace laureate Linus Pauling’s petition for a ban on nuclear weapons. To prove the survivability of nuclear war, Libby built a fallout shelter at his house, an event that was widely publicized. The shelter and house burned down several weeks later, however, which caused physicist and nuclear testing critic Leo Szilard to joke, “This proves not only that there is a God but that he has a sense of humor.”

While associated with the Manhattan Project (1941–45), Libby helped develop a method for separating uranium isotopes by gaseous diffusion, an essential step in the creation of the atomic bomb. In 1946 he showed that cosmic rays in the upper atmosphere produce traces of tritium, the heaviest isotope of hydrogen, which can be used as a tracer for atmospheric water. By measuring tritium concentrations, he developed a method for dating well water and wine, as well as for measuring circulation patterns of water and the mixing of ocean waters.

Because it had been known since 1939 that cosmic rays create showers of neutrons on striking atoms in the atmosphere, and because the atmosphere contains about 78 percent nitrogen, which absorbs neutrons to decay into the radioactive isotope carbon-14, Libby concluded that traces of carbon-14 should always exist in atmospheric carbon dioxide. Also, because carbon dioxide is continuously absorbed by plants and becomes part of their tissues, plants should contain traces of carbon-14. Since animals consume plants, animals should likewise contain traces of carbon-14. After a plant or other organism dies, no additional carbon-14 should be incorporated into its tissues, while that which is already present should decay at a constant rate. The half-life of carbon-14 was determined by its codiscoverer, chemist Martin D. Kamen, to be 5,730 years, which, compared with the age of the Earth, is a short time but one long enough for the production and decay of carbon-14 to reach equilibrium. In his Nobel presentation speech, Swedish chemist Arne Westgren summarized Libby’s method: “Because the activity of the carbon atoms decreases at a known rate, it should be possible, by measuring the remaining activity, to determine the time elapsed since death, if this occurred during the period between approximately 500 and 30,000 years ago.”

Libby verified the accuracy of his method by applying it to samples of fir and redwood trees whose ages had already been found by counting their annual rings and to artifacts, such as wood from the funerary boat of Pharaoh Sesostris III, whose ages were already known. By measuring the radioactivity of plant and animal material obtained globally from the North Pole to the South Pole, he showed that the carbon-14 produced by cosmic-ray bombardment varied little with latitude. On March 4, 1947, Libby and his students obtained the first age determination using the carbon-14 dating technique. He also dated linen wrappings from the Dead Sea Scrolls, bread from Pompeii buried in the eruption of Vesuvius (ad 79), charcoal from a Stonehenge campsite, and corncobs from a New Mexico cave, and he showed that the last North American ice age ended about 10,000 years ago, not 25,000 years ago as previously believed by geologists. The most publicized and controversial case of radiocarbon dating is probably that of the Shroud of Turin, which believers claim once covered the body of Jesus Christ but which Libby’s method applied by others shows to be from a period between 1260 and 1390. In nominating Libby for the Nobel Prize, one scientist stated, “Seldom has a single discovery in chemistry had such an impact on the thinking in so many fields of human endeavour. Seldom has a single discovery generated such wide public interest.”

It appears to me that if one wants to make progress in mathematics, one should study the masters and not the pupils. - Niels Henrik Abel.

Nothing is better than reading and gaining more and more knowledge - Stephen William Hawking.

Offline