Math Is Fun Forum

You are not logged in.

- Topics: Active | Unanswered

#1626 2024-10-24 15:34:11

- Jai Ganesh

- Administrator

- Registered: 2005-06-28

- Posts: 52,998

Re: crème de la crème

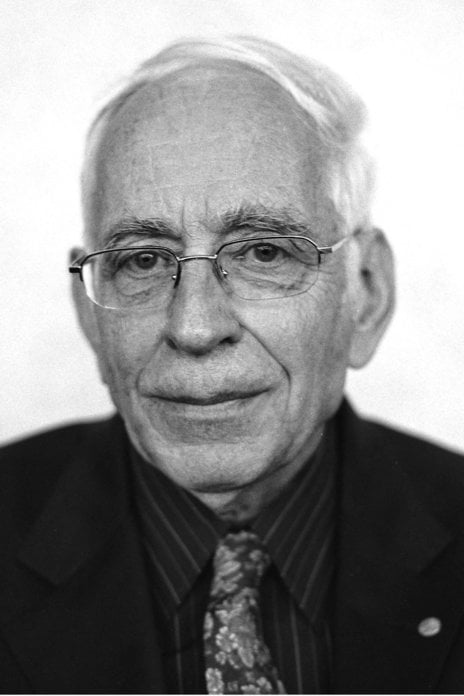

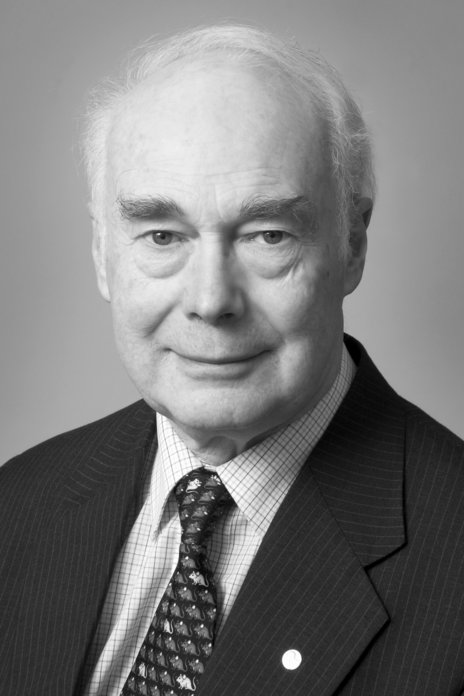

2088) Theodor W. Hänsch

Gist

Work

According to quantum physics, light and other electromagnetic radiation appear in the form of quanta, packets with fixed energies, which also correspond to energy transitions in atoms. Consequently, determining the frequency of light waves provides information about the atoms’ properties, benchmarks for time and length, and the possibility of determining physical constants. Around the year 2000, Theodor Hänsch and John Hall developed the frequency comb technique, in which laser light with a series of equidistant frequencies is used to measure frequencies with great precision.

Summary

Theodor W. Hänsch (born October 30, 1941, Heidelberg, Germany) is a German physicist who shared one-half of the 2005 Nobel Prize for Physics with John L. Hall for their contributions to the development of laser spectroscopy, the use of lasers to determine the frequency (color) of light emitted by atoms and molecules. (The other half of the award went to Roy J. Glauber.)

Hänsch received a Ph.D. in physics from the University of Heidelberg in 1969. The following year he moved to the United States and began teaching at Stanford University. In 1986 he returned to Germany to become director of the Max Planck Institute for Quantum Optics, a post he held until 2016. He also joined the faculty at Ludwig Maximilians University.

Hänsch’s prizewinning research centered on measuring optical frequencies (frequencies of visible light). Although a procedure known as an optical frequency chain had already been created to measure such frequencies, it was extremely complex and could be performed in only a few laboratories. In the late 1970s Hänsch originated the idea for the optical frequency comb technique, in which ultrashort pulses of laser light create a set of precisely spaced frequency peaks that resemble the evenly spaced teeth of a hair comb. The technique offered a practical way of obtaining optical frequency measurements to an accuracy of 15 digits, or one part in one quadrillion. Hänsch, using key contributions by Hall, worked out the theory’s details in 2000.

The success of Hall and Hänsch soon led to the development of commercial devices with which very precise optical frequency measurements could readily be made. Their work had a number of practical applications, including the improvement of satellite-based navigation systems, such as the Global Positioning System (GPS), and the synchronization of computer data networks. Physicists also used the two men’s findings to verify Albert Einstein’s theory of special relativity to very high levels of precision and to test whether the values of fundamental physical constants related to optical frequencies were indeed constant or changed slightly over time.

Details

Theodor Wolfgang Hänsch (born 30 October 1941) is a German physicist. He received one-third of the 2005 Nobel Prize in Physics for "contributions to the development of laser-based precision spectroscopy, including the optical frequency comb technique", sharing the prize with John L. Hall and Roy J. Glauber.

Hänsch is Director of the Max-Planck-Institut für Quantenoptik (quantum optics) and Professor of experimental physics and laser spectroscopy at the Ludwig-Maximilians University in Munich, Bavaria, Germany.

Biography

Hänsch received his secondary education at Helmholtz-Gymnasium Heidelberg and gained his Diplom and doctoral degree from Ruprecht-Karls-Universität Heidelberg in the 1960s. Subsequently, he was a NATO postdoctoral fellow at Stanford University with Arthur L. Schawlow from 1970 to 1972. Hänsch became an assistant professor at Stanford University, California from 1975 to 1986. He was awarded the Comstock Prize in Physics from the National Academy of Sciences in 1983. In 1986, he received the Albert A. Michelson Medal from the Franklin Institute. In the same year Hänsch returned to Germany to head the Max-Planck-Institut für Quantenoptik. In 1989, he received the Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz Prize of the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft, which is the highest honour awarded in German research. In 2005, he also received the Otto Hahn Award of the City of Frankfurt am Main, the Society of German Chemists and the German Physical Society. In that same year, the Optical Society of America awarded him the Frederic Ives Medal and the status of honorary member in 2008.

One of his students, Carl E. Wieman, received the Nobel Prize in Physics in 2001.

In 1970 he invented a new type of laser that generated light pulses with an extremely high spectral resolution (i.e. all the photons emitted from the laser had nearly the same energy, to a precision of 1 part in a million). Using this device he succeeded to measure the transition frequency of the Balmer line of atomic hydrogen with a much higher precision than before. During the late 1990s, he and his coworkers developed a new method to measure the frequency of laser light to an even higher precision, using a device called the optical frequency comb generator. This invention was then used to measure the Lyman line of atomic hydrogen to an extraordinary precision of 1 part in a hundred trillion. At such a high precision, it became possible to search for possible changes in the fundamental physical constants of the universe over time. For these achievements he became co-recipient of the Nobel Prize in Physics for 2005.

Background to Nobel Prize

The Nobel Prize was awarded to Professor Hänsch in recognition for work that he did at the end of the 1990s at the Max Planck Institute in Garching, near Munich, Germany. He developed an optical "frequency comb synthesiser", which makes it possible, for the first time, to measure with extreme precision the number of light oscillations per second. These optical frequency measurements can be millions of times more precise than previous spectroscopic determinations of the wavelength of light.

The work in Garching was motivated by experiments on the very precise laser spectroscopy of the hydrogen atom. This atom has a particularly simple structure. By precisely determining its spectral line, scientists were able to draw conclusions about how valid our fundamental physical constants are – if, for example, they change slowly with time. By the end of the 1980s, the laser spectroscopy of hydrogen had reached the maximum precision allowed by interferometric measurements of optical wavelengths.

The researchers at the Max Planck Institute of Quantum Optics thus speculated about new methods, and developed the optical frequency comb synthesizer. Its name comes from the fact that it generates a light spectrum out of what are originally single-colour, ultrashort pulses of light. This spectrum is made of hundreds of thousands of sharp spectral lines with a constant frequency interval.

Such a frequency comb is similar to a ruler. When the frequency of a particular radiation is determined, it can be compared to the extremely acute comb spectral lines, until one is found that "fits". In 1998, Professor Hänsch received a Philip Morris Research Prize for the development of this "measurement device".

One of the first applications of this new kind of light source was to determine the frequency of the very narrow ultraviolet hydrogen 1S-2S two-photon transition. Since then, the frequency has been determined with a precision of 15 decimal places.

The frequency comb now serves as the basis for optical frequency measurements in large numbers of laboratories worldwide. Since 2002, the company Menlo Systems, in whose foundation the Max Planck Institute in Garching played a role, has been delivering commercial frequency comb synthesizers to laboratories all over the world.

Laser development

Hänsch introduced intracavity telescopic beam expansion to grating tuned laser oscillators thus producing the first narrow-linewidth tunable laser. This development has been credited with having had a major influence in the development of further narrow-linewidth multiple-prism grating laser oscillators. In turn, tunable narrow-linewidth organic lasers, and solid-state lasers, using total illumination of the grating, have had a major impact in laser spectroscopy.

It appears to me that if one wants to make progress in mathematics, one should study the masters and not the pupils. - Niels Henrik Abel.

Nothing is better than reading and gaining more and more knowledge - Stephen William Hawking.

Offline

#1627 2024-10-31 16:02:42

- Jai Ganesh

- Administrator

- Registered: 2005-06-28

- Posts: 52,998

Re: crème de la crème

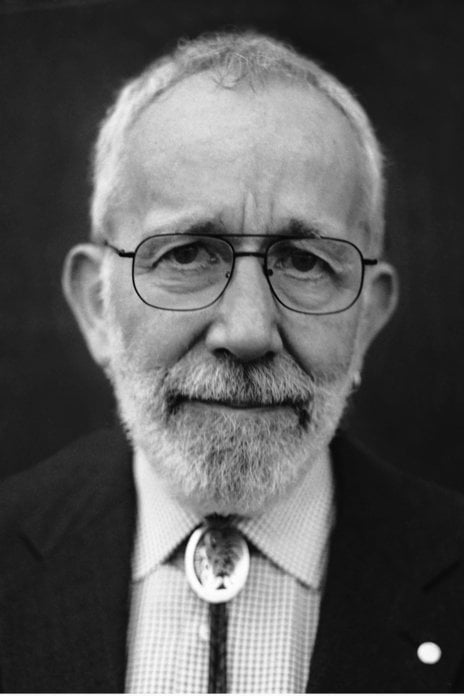

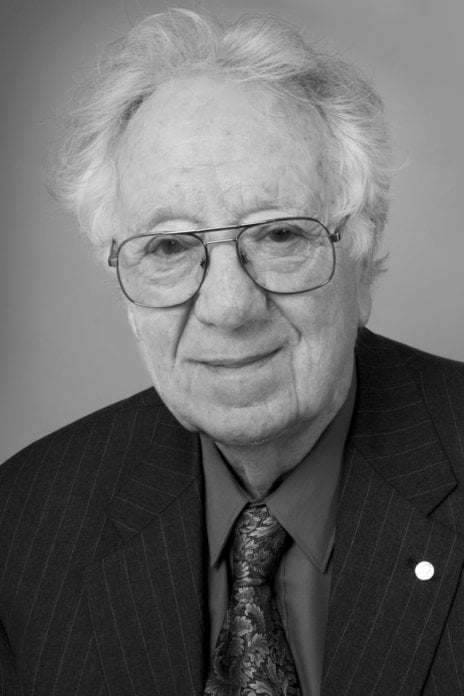

2089) Yves Chauvin

Gist:

Work

Organic substances—a multitude of chemical compounds that contain the element carbon—are the basis of all life. Metathesis is an important type of chemical reaction in assembling or synthesizing organic substances. In metathesis double bonds between carbon atoms are broken and reorganized at the same time as atomic groups change place. In 1971 Yves Chauvin showed how such reactions proceed in detail, including how certain metallic compounds facilitate the process. Metathesis has enabled more effective and environmentally sound processes in industry.

Summary

Yves Chauvin (born October 10, 1930, Menen, Belgium—died January 27, 2015, Tours, France) was a French chemist who was corecipient, with Robert H. Grubbs and Richard R. Schrock, of the Nobel Prize for Chemistry in 2005 for developing metathesis, an important chemical reaction used in organic chemistry. Chauvin offered a detailed explanation of “how metatheses reactions function and what types of metal compound act as catalysts in the reactions.”

Chauvin graduated in 1954 from the Lyon School of Chemistry, Physics, and Electronics. From 1960 he spent most of his career conducting research at the French Institute of Petroleum (IFP), where he was named research director in 1991 and honorary research director upon his retirement in 1995. Chauvin held several patents and developed valuable petrochemical industrial processes, notably in regard to homogeneous catalysis. He was elected a member of the French Academy of Sciences in 2005.

Chauvin’s work centred on metathesis, in which catalysts create and break double carbon bonds of organic molecules in a way that causes different groups of atoms in the molecules to change places with one another. The shift of groups of atoms from their original position to a new location yields new molecules with new properties. Researchers in the 1950s had found that various catalysts could be used to carry out metathesis reaction. However, since it was not understood how the catalysts worked at a molecular level, the hunt for better catalysts was purely a hit-and-miss endeavour. In the early 1970s Chauvin achieved a breakthrough when he described the mechanism by which a metal atom bound to a carbon atom in one group of atoms causes the group to shift places with a group of atoms in another molecule. Although the catalyst starts the chemical reaction in which two new carbon-carbon bonds are formed, it comes away from the chemical reaction unaffected and ready to start the reaction again. Chauvin’s work showed how metathesis could take place, but its practical application required the development of new catalysts, the first of which were discovered by Schrock (in 1990) and Grubbs (in 1992). Their work led to the development of many new products, including advanced plastics, fuel additives, and pharmaceuticals and played a role in the advancement of “green chemistry”—the design of chemical processes and products in which the need for and the generation of various hazardous substances were reduced or eliminated.

Details

Yves Chauvin (10 October 1930 – 27 January 2015) was a French chemist and Nobel Prize laureate. He was honorary research director at the Institut français du pétrole and a member of the French Academy of Science. He was known for his work for deciphering the process of olefin metathesis for which he was awarded the 2005 Nobel Prize in Chemistry along with Robert H. Grubbs and Richard R. Schrock.

Life

Yves Chauvin was born on 10 October 1930 in Menen, Belgium, to French parents; his father worked as an electrical engineer. He graduated in 1954 from the École supérieure de chimie physique électronique de Lyon. He began working in the chemical industry but was frustrated there. He is quoted as saying, "If you want to find something new, look for something new...there is a certain amount of risk in this attitude, as even the slightest failure tends to be resounding, but you are so happy when you succeed that it is worth taking the risk." In 1960, Chauvin began working for the French Petroleum Institute in Rueil-Malmaison. He became honorary director of research there following his retirement from the institute in 1995. Chauvin also served as an emeritus (retired) director of research at the Lyon School of Chemistry, Physics, and Electronics.

Awards and recognitions

He was awarded the 2005 Nobel Prize in Chemistry, along with Robert H. Grubbs and Richard R. Schrock, for his work from the early 1970s in the area of olefin metathesis. Chauvin was embarrassed to receive his award and initially indicated that he might not accept it. He did however receive his award from the King of Sweden and deliver his Nobel lecture. He was elected a member of the French Academy of Sciences in 2005.

Research

Chauvin's work centred on metathesis, which involves organic (carbon-based) compounds. In metathesis, chemists break double bonds more easily by introducing a catalyst—that is, a substance that starts or speeds up a chemical reaction. Chemists began performing metathesis in the 1950s without knowing exactly how the reaction worked. This lack of understanding hindered the search for more efficient catalysts.

In the early 1970s Chauvin achieved a breakthrough when he described the mechanism by which a metal atom bound to a carbon atom in one group of atoms causes the group to shift places with a group of atoms in another molecule and explained metathesis in detail. He showed that the reaction involves two double bonds. One of the double bonds connects two parts of an organic molecule. The other double bond connects a metal-based catalyst to a fragment of an organic molecule. In metathesis, these two double bonds combine and split to make four single bonds. The single bonds form a ring that connects the metal catalyst, the organic fragment, and the two parts of the organic molecule. The metal catalyst then breaks off from the ring, carrying away part of the organic molecule. This process leaves the fragment attached to the remainder of the organic molecule with a double bond, forming a new organic compound. Scholars have compared this reaction to a dance in which two sets of partners join hands to form a ring and then split apart again to form two new partnerships.

Chauvin's description of metathesis led Robert H. Grubbs and Richard R. Schrock to develop catalysts that carried out the reaction more efficiently. The three chemists' work has enabled manufacturers to make organic compounds, including some plastics and medicines, using less energy because the required reaction pressures and temperatures became lower, and using fewer harmful and expensive chemicals, and creating fewer contaminant reaction by-products and hazardous waste that must be extracted from the desired synthetic. It was for this process they were awarded with 2005 Chemistry Nobel Prize.

Death

Chauvin died, at the age of 84, on 27 January 2015 in Tours, France.

It appears to me that if one wants to make progress in mathematics, one should study the masters and not the pupils. - Niels Henrik Abel.

Nothing is better than reading and gaining more and more knowledge - Stephen William Hawking.

Offline

#1628 2024-11-01 16:31:01

- Jai Ganesh

- Administrator

- Registered: 2005-06-28

- Posts: 52,998

Re: crème de la crème

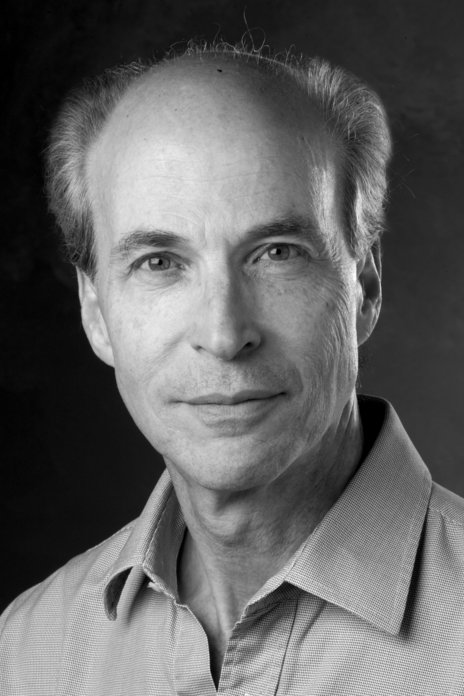

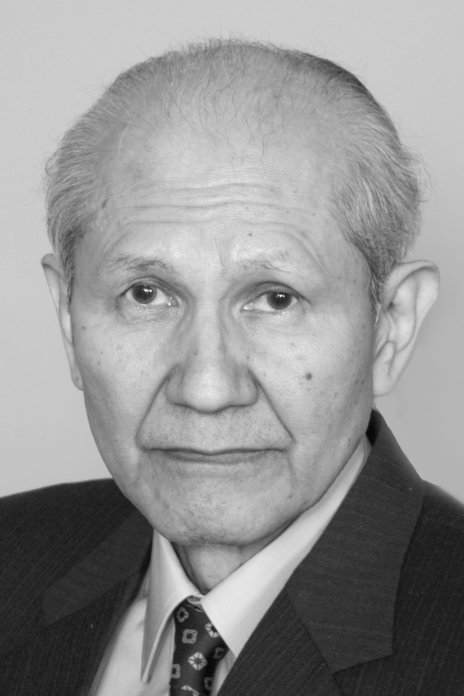

2090) Robert H. Grubbs

Gist:

Work

Organic substances—a multitude of chemical compounds that contain the element carbon—are the basis of all life. Metathesis is an important type of chemical reaction in assembling or synthesizing organic substances. In metathesis double bonds between carbon atoms are broken and reorganized at the same time as atomic groups change place. Around 1992 Robert Grubbs discovered a metallic compound that effectively facilitates metathesis and is stable in the air. Metathesis has enabled more effective and environmentally sound processes in industry.

Summary

Robert H. Grubbs (born February 27, 1942, near Possum Trot, Kentucky, U.S.—died December 19, 2021, Duarte, California) was an American chemist who, with Richard R. Schrock and Yves Chauvin, won the Nobel Prize for Chemistry in 2005 for developing metathesis, an important type of chemical reaction used in organic chemistry. Schrock and Grubbs were honoured for their advances in more-effective catalysts based on a mechanism first proposed by Chauvin.

Grubbs studied chemistry at the University of Florida (B.S., 1963; M.S., 1965) and at Columbia University, New York City (Ph.D., 1968). After a year as a postdoctoral fellow at Stanford University, he joined the chemistry faculty at Michigan State University. In 1978 he moved to the California Institute of Technology, where he was named the Victor and Elizabeth Atkins Professor of Chemistry in 1990.

Grubbs’s prizewinning research centred on metathesis, a reaction in which catalysts create and break double carbon bonds of organic molecules in a way that causes different groups of atoms in the molecules to change places with one another. This changing of places results in new molecules with new properties. Building on the work of Chauvin, who in the 1970s had shown how metathesis could take place, Grubbs and his associates in 1992 reported the discovery of a catalyst that contained the metal ruthenium. It was stable in air and worked on the double carbon bonds in a molecule selectively, without disrupting the bonds between other atoms in the molecule, unlike the significant but unstable molybdenum-based catalysts reported by Schrock two years earlier. The new catalyst also had the ability to jump-start metathesis reactions in the presence of water, alcohols, and carboxyl acids. Grubbs’s discovery helped pave the way for practical applications of metathesis, including the development of new products such as advanced plastics and pharmaceuticals. Catalysts used in metathesis also contributed to the rise of “green chemistry,” which involves using techniques that minimize pollution in chemical processes.

Details

Robert Howard Grubbs ForMemRS (February 27, 1942 – December 19, 2021) was an American chemist and the Victor and Elizabeth Atkins Professor of Chemistry at the California Institute of Technology in Pasadena, California. He was a co-recipient of the 2005 Nobel Prize in Chemistry for his work on olefin metathesis.

Grubbs was elected a member of the National Academy of Engineering in 2015 for developments in catalysts that have enabled commercial products.

He was a co-founder of Materia, a university spin-off startup to produce catalysts.

Early life and education

Grubbs was born on February 27, 1942, on a farm in Marshall County, Kentucky, midway between Possum Trot and Calvert City. His parents were Howard and Faye (Atwood) Grubbs. Faye was a schoolteacher. After serving in World War II, the family moved to Paducah, Kentucky, where Howard trained as a diesel mechanic, and Robert attended Paducah Tilghman High School.

At the University of Florida, Grubbs initially intended to study agriculture chemistry. However, he was convinced by professor Merle A. Battiste to switch to organic chemistry. Working with Battiste, he became interested in how chemical reactions occur. He received his B.S. in 1963 and M.S. in 1965 from the University of Florida.

Next, Grubbs attended Columbia University, where he worked with Ronald Breslow on organometallic compounds which contain carbon-metal bonds. Grubbs received his Ph.D. in 1968.

Career

Grubbs worked with James Collman at Stanford University as a National Institutes of Health fellow during 1968–1969. With Collman, he began to systematically investigate catalytic processes in organometallic chemistry, a then relatively new area of research.

In 1969, Grubbs was appointed to the faculty of Michigan State University, where he began his work on olefin metathesis. Harold Hart, Gerasimos J. Karabatsos, Gene LeGoff, Don Farnum, Bill Reusch and Pete Wagner served as his early mentors at MSU. Grubbs was an assistant professor from 1969 to 1973, and an associate professor from 1973 to 1978.[16] He received a Sloan Fellowship for 1974–1976. In 1975, he went to the Max Planck Institute for Coal Research in Mülheim, Germany, on a fellowship from the Alexander von Humboldt Foundation.

In 1978, Grubbs moved to California Institute of Technology as a professor of chemistry. As of 1990 he became the Victor and Elizabeth Atkins Professor of Chemistry.

As of 2021, Grubbs has an h-index of 160 according to Google Scholar and of 137 according to Scopus.

It appears to me that if one wants to make progress in mathematics, one should study the masters and not the pupils. - Niels Henrik Abel.

Nothing is better than reading and gaining more and more knowledge - Stephen William Hawking.

Offline

#1629 2024-11-02 15:55:12

- Jai Ganesh

- Administrator

- Registered: 2005-06-28

- Posts: 52,998

Re: crème de la crème

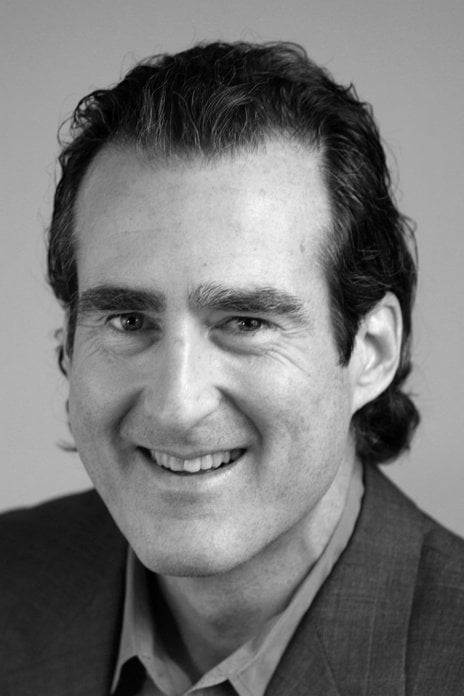

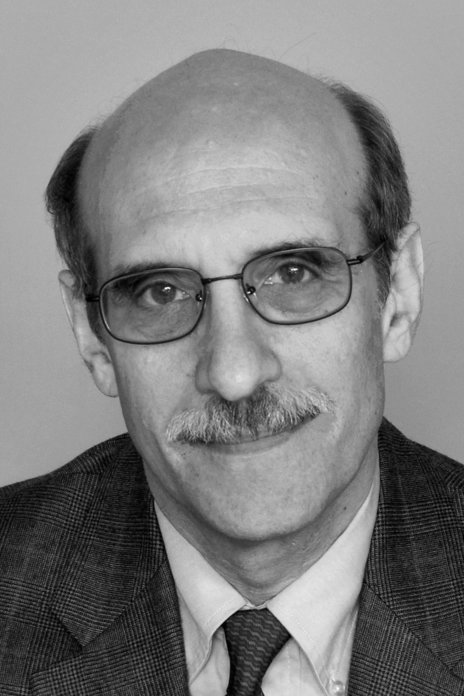

2091) Richard R. Schrock

Gist:

Life

Richard Schrock was born in Berne, Indiana, in the U.S. After studies at the University of California, Riverside, he received his doctor’s degree at Harvard University in 1971. After a few years as a researcher at the DuPont chemical company in Wilmington, Delaware, he began working at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, where he has remained ever since. He has also been actively involved in a company engaged in development and applications within his research area. Richard Schrock is married and has two children.

Work

Organic substances—a multitude of chemical compounds that contain the element carbon—are the basis of all life. Metathesis is an important type of chemical reaction in assembling or synthesizing organic substances. In metathesis double bonds between carbon atoms are broken and reorganized at the same time as atomic groups change place. In 1990 Richard Schrock succeeded in producing a metallic compound that effectively facilitates metathesis. Metathesis has enabled more effective and environmentally sound processes in industry.

Summary

Richard R. Schrock (born Jan. 4, 1945, Berne, Ind., U.S.) is an American chemist who, with Robert H. Grubbs and Yves Chauvin, was awarded the Nobel Prize for Chemistry in 2005 for developing metathesis, one of the most important types of chemical reactions used in organic chemistry. Schrock was honoured as “the first to produce an efficient metal-compound catalyst for metathesis.”

Schrock received a B.A. (1967) from the University of California, Riverside, and a Ph.D. (1971) from Harvard University. He held a one-year National Science Foundation postdoctoral fellowship at the University of Cambridge and spent three years doing research at E.I. du Pont de Nemours and Co. In 1975 he joined the faculty at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), where he was named the Frederick G. Keyes Professor of Chemistry in 1989. Schrock also served as associate editor of the American Chemical Society journal Organometallics, and he won the 1996 ACS Award in Inorganic Chemistry for his work in inorganic polymer chains.

At MIT Schrock conducted research on metathesis, a reaction in which catalysts create and break double carbon bonds of organic molecules in a way that causes different groups of atoms in the molecules to change places with one another. This shift yields new molecules with new properties. Working with a mechanism first proposed in the early 1970s by Chauvin, he systematically tested catalysts that contained tantalum, tungsten, or other metals in an effort to understand which metals could be used and how they worked. In a major advance in 1990 Schrock and his associates reported the development of efficient metathesis catalysts that used the metal molybdenum. Their chemistry was based on a class of metal-containing compounds, called Schrock carbenes, that Schrock had been developing since the 1970s. The new metathesis catalysts, however, were sensitive to the effects of air and water, which reduced their activity. (Grubbs later discovered catalysts that solved this particular problem.) Schrock’s work contributed to the development of many useful products, including advanced plastics, fuel additives, agents to control harmful plants and insects, and new drugs. Catalysts for metathesis also played a role in the creation of “green chemistry,” in which the need for and the generation of hazardous substances in chemical processes were reduced or eliminated.

Details

Richard Royce Schrock (born January 4, 1945) is an American chemist and Nobel laureate recognized for his contributions to the olefin metathesis reaction used in organic chemistry.

Education

Born in Berne, Indiana, Schrock went to Mission Bay High School in San Diego, California. He holds a B.A. (1967) from the University of California, Riverside and a Ph.D. (1971) from Harvard University under the direction of John A. Osborn (fr).

Career

Following his PhD, Schrock carried out postdoctoral research at the University of Cambridge with Jack Lewis. In 1972, he was hired by DuPont, where he worked at the Experimental Station in Wilmington, Delaware in the group of George Parshall. He joined the faculty of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in 1975 and became full professor in 1980.

He has been the Frederick G. Keyes Professor of Chemistry, at MIT since 1989, and is now Professor Emeritus. Schrock is a member of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, National Academy of Sciences and was elected to the Board of Overseers of Harvard University in 2007.

He is co-founder and member of the board of a Swiss-based company, XiMo, inc., now owned by Verbio, AG, which is focused on the development and application of proprietary metathesis catalysts.

In 2018, Schrock joined the faculty of his alma mater, the University of California, Riverside, where he is now the Distinguished Professor and George K. Helmkamp Founder's Chair of Chemistry. He cited his interest in mentoring junior faculty and students. “My experience as an undergraduate at UCR in research in the laboratory of James Pitts and the quality of the classes in chemistry prepared me for my Ph.D. experience at Harvard. I look forward to returning to UCR for a few years to give back some of what it gave to me,” Schrock said.

Research

In 1974 Schrock discovered the alpha hydrogen abstraction reaction, which creates alkylidene complexes from alkyls and alkylidyne complexes from alkylidenes. At MIT Schrock was the first to elucidate the structure and mechanism of so-called 'black box' olefin metathesis catalysts. He showed that the alpha abstraction reaction could be used to prepare molybdenum or tungsten alkylidene and alkylidyne complexes in large variety through ligand variations. Catalysts could then be designed at a molecular level for a given purpose. Schrock has done much work to demonstrate that metallacyclobutanes are the key intermediates in olefin metathesis, while metallacyclobutadienes are the key intermediates in alkyne metathesis. Projects outside of metathesis include elucidating the mechanism of dinitrogen fixation and developing single molecule catalysts which form ammonia from dinitrogen, mimicking the activity of nitrogenase enzymes in biology.

It appears to me that if one wants to make progress in mathematics, one should study the masters and not the pupils. - Niels Henrik Abel.

Nothing is better than reading and gaining more and more knowledge - Stephen William Hawking.

Offline

#1630 2024-11-03 16:31:56

- Jai Ganesh

- Administrator

- Registered: 2005-06-28

- Posts: 52,998

Re: crème de la crème

2092) Barry Marshall

Gist:

Life

Barry Marshall was born in Kalgoorlie, Australia, but spent his childhood from the age of eight in Perth, where he also studied to become a doctor. It was during his employment at the Royal Perth Hospital that he carried out the work with colleague Robin Warren that led to his receiving the Nobel Prize. Marshall has continued his affiliation with the hospital and university in Perth, but is also connected to US universities, including the University of Virginia in Charlottesville. Barry Marshall is married with four children.

Work

Gastric ulcers are a common illness, but their cause was long unknown. It was discovered that the most common cause is bacterial infection. After Robin Warren discovered colonies of bacteria at gastric ulcer sites, he was contacted by his colleague Barry Marshall, who then successfully cultivated the previously unknown bacteria Helicobacter pylori. Warren and Marshall proved in 1982 that patients could only be cured if the bacteria were eliminated. This is now achieved by treatment with antibiotics, and gastric ulcers are no longer a chronic illness.

Summary

Barry J. Marshall (born September 30, 1951, Kalgoorlie, Western Australia, Australia) is an Australian physician who won, with J. Robin Warren, the 2005 Nobel Prize for Physiology or Medicine for their discovery that stomach ulcers are an infectious disease caused by bacteria.

Marshall obtained a bachelor’s degree from the University of Western Australia in 1974. From 1977 to 1984 he worked at Royal Perth Hospital, and he later taught medicine at the University of Western Australia, where he also was a research fellow.

In the early 1980s Marshall became interested in the research of Warren, who in 1979 had first observed the presence of spiral-shaped bacteria in a biopsy of a patient’s stomach lining. The two began working together to determine the significance of the bacteria. They conducted a study of stomach biopsies from 100 patients that systematically showed that the bacteria were present in almost all patients with gastritis, duodenal ulcer, or gastric ulcer. Based on these findings, Warren and Marshall proposed that the bacterium Helicobacter pylori was involved in causing those diseases. This contradicted the commonly held belief that peptic ulcers resulted from an excess of gastric acid that was released in the stomach as the result of emotional stress, the ingestion of spicy foods, or other factors. It also challenged the traditional treatments, which included antacid medicines and dietary changes, by supporting a curative regimen of antibiotics and acid-secretion inhibitors. Hoping to persuade skeptics, Marshall drank a culture of H. pylori and within a week began suffering stomach pain and other symptoms of acute gastritis. Stomach biopsies confirmed that he had gastritis and showed that the affected areas of his stomach were infected with H. pylori. Marshall subsequently took antibiotics and was cured.

Prior to winning the Nobel Prize, Marshall had received the Albert Lasker Clinical Medical Research Award (1995) and the Benjamin Franklin Medal (1999) for his work on H. pylori. He also wrote several books, including Helicobacter Pioneers (2002), a collection of historical first-hand accounts of scientists who studied Helicobacter.

Details

Barry James Marshall (born 30 September 1951) is an Australian physician, Nobel Laureate in Physiology or Medicine, Professor of Clinical Microbiology and Co-Director of the Marshall Centre at the University of Western Australia. Marshall and Robin Warren showed that the bacterium Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) plays a major role in causing many peptic ulcers, challenging decades of medical doctrine holding that ulcers were caused primarily by stress, spicy foods, and too much acid. This discovery has allowed for a breakthrough in understanding a causative link between Helicobacter pylori infection and stomach cancer.

Early life and education

Marshall was born in Kalgoorlie, Western Australia and lived in Kalgoorlie and Carnarvon until moving to Perth at the age of eight. His father held various jobs, and his mother was a nurse. He is the eldest of four siblings. He attended Marist College, Churchlands for his secondary education and the University of Western Australia School of Medicine, where he received a Bachelor of Medicine, Bachelor of Surgery (MBBS) in 1974. He married his wife Adrienne in 1972 and has four children, a son and three daughters.

Career and research

In 1979, Marshall was appointed Registrar in Medicine at the Royal Perth Hospital. He met Dr. Robin Warren, a pathologist interested in gastritis, during internal medicine fellowship training at Royal Perth Hospital in 1981. Together, they both studied the presence of spiral bacteria in association with gastritis. In 1982, they performed the initial culture of H. pylori and developed their hypothesis on the bacterial cause of peptic ulcers and gastric cancer. It has been claimed that the H. pylori theory was ridiculed by established scientists and doctors, who did not believe that any bacteria could live in the acidic environment of the stomach. Marshall was quoted as saying in 1998 that "everyone was against me, but I knew I was right." On the other hand, it has also been argued that medical researchers showed a proper degree of scientific scepticism until the H. pylori hypothesis could be supported by evidence.

In 1982 Marshall and Warren obtained funding for one year of research. The first 30 out of 100 samples showed no support for their hypothesis. However, it was discovered that the lab technicians had been throwing out the cultures after two days. This was standard practice for throat swabs where other organisms in the mouth rendered cultures unusable after two days. Due to other hospital work, the lab technicians did not have time to immediately throw out the 31st test on the second day, and so it stayed from Thursday through to the following Monday. In that sample, they discovered the presence of H. pylori. They later found out that H. pylori grows more slowly than the conventional two days required by other mucosal bacteria, and that stomach cultures were not contaminated by other organisms.

In 1983 they submitted their findings thus far to the Gastroenterological Society of Australia, but the reviewers turned their paper down, rating it in the bottom 10% of those they received that year.

After failed attempts to infect piglets in 1984, Marshall, after having a baseline endoscopy done, drank a broth containing cultured H. pylori, expecting to develop, perhaps years later, an ulcer. He was surprised when, only three days later, he developed vague nausea and halitosis, due to the achlorhydria. There was no acid to kill bacteria in the stomach and their waste products manifested as bad breath, noticed by his wife. On days 5–8, he developed achlorhydric (no acid) vomiting. On day eight, he had a repeat endoscopy, which showed massive inflammation (gastritis), and a biopsy from which H. pylori was cultured, showing it had colonised his stomach. On the fourteenth day after ingestion, a third endoscopy was done, and Marshall began to take antibiotics. Marshall did not develop antibodies to H. pylori, suggesting that innate immunity can sometimes eradicate acute H. pylori infection. Marshall's illness and recovery, based on a culture of organisms extracted from a patient, fulfilled Koch's postulates for H. pylori and gastritis, but not for peptic ulcers. This experiment was published in 1985 in the Medical Journal of Australia and is among the most cited articles from the journal.

After his work at Fremantle Hospital, Marshall did research at Royal Perth Hospital (1985–86) and at the University of Virginia, USA (1986–present), before returning to Australia while remaining on the faculty of the University of Virginia. He held a Burnet Fellowship at the University of Western Australia (UWA) from 1998 to 2003. Marshall continues research related to H. pylori and runs the H. pylori Research Laboratory at UWA.

In 2007, Marshall was appointed Co-Director of The Marshall Centre for Infectious Diseases Research and Training, founded in his honour. In addition to Helicobacter pylori research, the Centre conducted varied research into infectious disease identification and surveillance, diagnostics and drug design, and transformative discovery. His research group expanded to embrace new technologies, including Next-Generation Sequencing and genomic analysis. Marshall also accepted a part-time appointment at the Pennsylvania State University that same year. He established the Noisy Guts Project in 2017 – a research team dedicated to investigating new diagnostics and treatments for Irritable Bowel Syndrome. This resulted in a spin-out company Noisy Guts Pty Ltd which develops functional food products. In August 2020, Marshall, along with Simon J. Thorpe, accepted a position at the scientific advisory board of Brainchip INC, a computer chip company.

It appears to me that if one wants to make progress in mathematics, one should study the masters and not the pupils. - Niels Henrik Abel.

Nothing is better than reading and gaining more and more knowledge - Stephen William Hawking.

Offline

#1631 2024-11-04 15:25:51

- Jai Ganesh

- Administrator

- Registered: 2005-06-28

- Posts: 52,998

Re: crème de la crème

2093) Robin Warren

Gist:

Life

Robin Warren was born in Adelaide, Australia. Warren received a bachelor’s degree from the University of Adelaide in 1961. He worked at several hospitals before becoming a pathologist at Royal Perth Hospital in 1968, where he began collaborating with co-recipient Barry Marshall. Warren’s wife Winifred, used to read their papers and suggest ways of making their work more widely readable. Warren retired in 1999, after which he has spent time performing his hobby, photography.

Work

Gastric ulcers are a common illness, but their cause was long unknown. It was discovered that the most common cause is bacterial infection. After Robin Warren discovered colonies of bacteria at gastric ulcer sites, he was contacted by his colleague Barry Marshall, who then successfully cultivated the previously unknown bacteria Helicobacter pylori. Warren and Marshall proved in 1982 that patients could only be cured if the bacteria were eliminated. This is now achieved by treatment by antibiotics, and gastric ulcers are no longer a chronic disease.

Summary

Robin Warren (born June 11, 1937, Adelaide, South Australia, Australia—died July 23, 2024, Perth, Western Australia) was an Australian pathologist who was corecipient, with Barry J. Marshall, of the 2005 Nobel Prize for Physiology or Medicine for their discovery that stomach ulcers are an infectious disease caused by bacteria.

Warren received a bachelor’s degree from the University of Adelaide in 1961. He worked at several hospitals before becoming in 1968 a pathologist at Royal Perth Hospital, where he remained until his retirement in 1999.

When Warren began his prizewinning research, physicians believed that peptic ulcers (sores in the stomach lining) were caused by an excess of gastric acid, which was commonly blamed on a stressful lifestyle or rich diet. In 1979 he first observed the presence of spiral-shaped bacteria in a biopsy of the stomach lining from a patient. It defied the conventional wisdom that bacteria could not survive in the highly acidic environment of the stomach, and many scientists dismissed his reports. His research during the next two years showed, however, that the bacteria were often in stomach tissue and almost always in association with gastritis (an inflammation of the stomach lining).

In the early 1980s Warren began working with Marshall to pin down the clinical significance of the bacteria. They studied 100 stomach biopsies and found that the bacteria were present in almost all patients with gastritis, duodenal ulcer, or gastric ulcer. Citing these findings, Warren and Marshall proposed that the bacterium Helicobacter pylori was involved in causing those illnesses. Their work led to a new treatment—a regimen of antibiotics and acid-secretion inhibitors—for peptic ulcer disease.

In 2007 Warren was made a Companion of the Order of Australia.

Details

John Robin Warren (11 June 1937 – 23 July 2024) was an Australian pathologist, Nobel laureate, and researcher who is credited with the 1979 re-discovery of the bacterium Helicobacter pylori, together with Barry Marshall. The duo proved to the medical community that the bacterium Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) is the cause of most peptic ulcers.

Early life and education

Warren received his M.B.B.S. degree from the University of Adelaide, having completed his high school education at St Peter's College, Adelaide.

Career

Warren trained at the Royal Adelaide Hospital and became a Registrar in Clinical Pathology at the Institute of Medical and Veterinary Science (IMVS). There, he worked in laboratory haematology, which generated his interest in pathology.

In 1963, Warren was appointed Honorary Clinical Assistant in Pathology and Honorary Registrar in Haematology at Royal Adelaide Hospital. Subsequently, he lectured in pathology at Adelaide University and then became Clinical Pathology Registrar at the Royal Melbourne Hospital. In 1967, Warren was elected to the Royal College of Pathologists of Australasia and became a senior pathologist at the Royal Perth Hospital, where he spent the majority of his career.

Nobel Prize work

At the University of Western Australia, with his colleague Barry J. Marshall, Warren proved that the bacterium is the infectious cause of stomach ulcers. Warren helped develop a convenient diagnostic test (14

C-urea breath-test) for detecting H. pylori in ulcer patients.

In 2005, Warren and Marshall were awarded the Nobel Prize in Medicine.

An Australian documentary was made in 2006 about Warren and Marshall's road to the Nobel Prize, called "The Winner's Guide to the Nobel Prize". He was appointed a Companion of the Order of Australia in 2007.

Asteroid 254863 Robinwarren, discovered by Italian amateur astronomer Silvano Casulli in 2005, was named in his honour. The official naming citation was published by the Minor Planet Center on 22 April 2016 (M.P.C. 99893).

Personal life and death

Warren married Winifred Theresa Warren (née Williams) in the early 1960s, and together they had five children. Winifred Warren became an accomplished psychiatrist. Following her death in 1997, Warren retired from medicine.

Warren died in Perth, Australia, on 23 July 2024, at the age of 87.

It appears to me that if one wants to make progress in mathematics, one should study the masters and not the pupils. - Niels Henrik Abel.

Nothing is better than reading and gaining more and more knowledge - Stephen William Hawking.

Offline

#1632 2024-11-05 15:53:26

- Jai Ganesh

- Administrator

- Registered: 2005-06-28

- Posts: 52,998

Re: crème de la crème

2094) John C. Mather

Gist:

Work

Various types of particles and radiation travel through outer space, including cosmic background radiation, which has been carefully studied through measurements from the COBE satellite. John Mather, a driving force in the project, had particular responsibility for a part that in 1989 indicated that cosmic background radiation’s spectrum corresponds to black-body radiation—radiation emitted by a dark, glowing body. The result provided evidence that the background radiation is a remnant from the creation of the universe in the Big Bang.

Summary

John C. Mather (born August 7, 1946, Roanoke, Virginia, U.S.) is an American physicist, who was corecipient, with George F. Smoot, of the 2006 Nobel Prize for Physics for discoveries supporting the big-bang model.

Mather studied physics at Swarthmore University (B.S., 1968) and the University of California at Berkeley (Ph.D., 1974). He later joined the staff of the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) Goddard Space Flight Center, serving as a senior astrophysicist.

In the 1980s Mather and Smoot were instrumental in developing the Cosmic Background Explorer (COBE) for NASA. The satellite was launched in 1989 and measured cosmic microwave background radiation formed during the early phases of creation of the universe. The resulting data supports the hypothesis that the universe emerged from a state of high temperature and density—the so-called big bang that occurred at least 10 billion years ago.

In 1995 Mather became the senior project scientist for the James Webb Space Telescope, which was launched in 2021. He wrote a book about the COBE project, The Very First Light: The True Inside Story of the Scientific Journey Back to the Dawn of the Universe (1996, revised 2008, with John Boslough).

Details

John Cromwell Mather (born August 7, 1946) is an American astrophysicist, cosmologist and Nobel Prize in Physics laureate for his work on the Cosmic Background Explorer Satellite (COBE) with George Smoot.

This work helped cement the big-bang theory of the universe. According to the Nobel Prize committee, "the COBE-project can also be regarded as the starting point for cosmology as a precision science."

Mather is a senior astrophysicist at the NASA Goddard Space Flight Center (GSFC) in Maryland and adjunct professor of physics at the University of Maryland College of Computer, Mathematical, and Natural Sciences. In 2007, Time magazine listed Mather among the 100 Most Influential People in The World. In October 2012, he was listed again by Time magazine in a special issue on New Space Discoveries as one of the 25 most influential people in space.

Mather is one of the 20 American recipients of the Nobel Prize in Physics to sign a letter addressed to President George W. Bush in May 2008, urging him to "reverse the damage done to basic science research in the Fiscal Year 2008 Omnibus Appropriations Bill" by requesting additional emergency funding for the Department of Energy's Office of Science, the National Science Foundation, and the National Institute of Standards and Technology.

Mather served as the senior project scientist for the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) from 1995 until 2023, when he was succeeded by Jane Rigby.

In 2014, Mather delivered an address on the James Webb Space Telescope at the second Starmus Festival in the Canary Islands.

It appears to me that if one wants to make progress in mathematics, one should study the masters and not the pupils. - Niels Henrik Abel.

Nothing is better than reading and gaining more and more knowledge - Stephen William Hawking.

Offline

#1633 2024-11-06 16:50:55

- Jai Ganesh

- Administrator

- Registered: 2005-06-28

- Posts: 52,998

Re: crème de la crème

2095) George Smoot

Gist:

Life

George Smoot was born in Yukon, Florida, into a family where many practiced law. His father, however, broke with tradition and became an engineer, while his mother taught school. His parents strongly encouraged his interest in mathematics and physics when he was growing up, and Sputnik drew both his and the world’s attention to space. Money was scarce in the family, and during his time at school, Smoot worked to earn extra money so he could afford studies at MIT. After his doctorate, he moved to Berkeley, where he made his Nobel Prize-winning discoveries.

Work

Various types of particles and radiation travel through outer space, including cosmic background radiation, which has been carefully studied through measurements from the COBE satellite. George Smoot led a project that in 1992 was able to point out small variations in radiation in different directions. This provides a clue to how stars and other heavenly bodies have come into existence. The variations can be explained by a kind of quantum mechanical fluctuations that have caused matter in certain places to form clumps that then have grown because of gravitation.

Summary

George F. Smoot (born Feb. 20, 1945, Yukon, Fla., U.S.) is an American physicist, who was corecipient, with John C. Mather, of the Nobel Prize for Physics in 2006 for discoveries supporting the big-bang model.

Smoot received a Ph.D. in physics from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in 1970. The following year he joined the faculty at the University of California at Berkeley.

In the 1980s Smoot and Mather helped develop the Cosmic Background Explorer (COBE) for the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA). Launched in 1989, the satellite measured the cosmic microwave background radiation formed during the early phases of creation of the universe. The resulting data support the theory that the universe was created in a primordial explosion known as the big bang.

Details

George Fitzgerald Smoot III (born February 20, 1945) is an American astrophysicist, cosmologist, Nobel laureate, and the second contestant to win the $1 million prize on Are You Smarter than a 5th Grader? He won the Nobel Prize in Physics in 2006 for his work on the Cosmic Background Explorer with John C. Mather that led to the "discovery of the black body form and anisotropy of the cosmic microwave background radiation".

This work helped further the Big Bang theory of the universe using the Cosmic Background Explorer (COBE) satellite. According to the Nobel Prize committee, "the COBE project can also be regarded as the starting point for cosmology as a precision science." Smoot donated his share of the Nobel Prize money, less travel costs, to a charitable foundation.

Smoot has been at the University of California, Berkeley and the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory since 1970. He is Chair of the Endowment Fund "Physics of the Universe" of Paris Center for Cosmological Physics. Apart from being elected a member of the US National Academy of Sciences and a Fellow of the American Physical Society, Smoot has been honored by several universities worldwide with doctorates or professorships. He was also the recipient of the Gruber Prize in Cosmology (2006), the Daniel Chalonge Medal from the International School of Astrophysics (2006), the Einstein Medal from the Albert Einstein Society (2003), the Ernest Orlando Lawrence Award from the US Department of Energy (1995), and the Exceptional Scientific Achievement Medal from NASA (1991). He is a member of the advisory board of the journal Universe.

Smoot is one of the 20 American recipients of the Nobel Prize in Physics to sign a letter addressed to President George W. Bush in May 2008, urging him to "reverse the damage done to basic science research in the Fiscal Year 2008 Omnibus Appropriations Bill" by requesting additional emergency funding for the Department of Energy's Office of Science, the National Science Foundation, and the National Institute of Standards and Technology.

Early life

Smoot was born in Yukon, Florida. His maternal grandfather was Johnson Tal Crawford. He graduated from Upper Arlington High School in Upper Arlington, Ohio, in 1962. He studied mathematics before switching to physics at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, where he obtained dual bachelor's degrees in mathematics and physics in 1966 and a Ph.D. in particle physics in 1970. A distant relative, Oliver R. Smoot, was the MIT student who was used as the unit of measure known as the smoot.

Initial research

George Smoot switched to cosmology and began work at Berkeley, collaborating with Luis Walter Alvarez on the High Altitude Particle Physics Experiment, a stratospheric weather balloon designed to detect antimatter in Earth's upper atmosphere, the presence of which was predicted by the now discredited steady state theory of cosmology.

He then took up an interest in cosmic microwave background radiation (CMB), previously discovered by Arno Allan Penzias and Robert Woodrow Wilson in 1964. There were, at that time, several open questions about this topic, relating directly to fundamental questions about the structure of the universe. Certain models predicted the universe as a whole was rotating, which would have an effect on the CMB: its temperature would depend on the direction of observation. With the help of Alvarez and Richard A. Muller, Smoot developed a differential radiometer which measured the difference in temperature of the CMB between two directions 60 degrees apart. The instrument, which was mounted on a Lockheed U-2 plane, made it possible to determine that the overall rotation of the universe was zero, which was within the limits of accuracy of the instrument. It did, however, detect a variation in the temperature of the CMB of a different sort. That the CMB appears to be at a higher temperature on one side of the sky than on the opposite side, referred to as a dipole pattern, has been explained as a Doppler effect of the Earth's motion relative to the area of CMB emission, which is called the last scattering surface. Such a Doppler effect arises because the Sun, and in fact the Milky Way as a whole, is not stationary, but rather is moving at nearly 600 km/s with respect to the last scattering surface. This is probably due to the gravitational attraction between our galaxy and a concentration of mass like the Great Attractor.

COBE

At that time, the CMB appeared to be perfectly uniform excluding the distortion caused by the Doppler effect as mentioned above. This result contradicted observations of the universe, with various structures such as galaxies and galaxy clusters indicating that the universe was relatively heterogeneous on a small scale. However, these structures formed slowly. Thus, if the universe is heterogeneous today, it would have been heterogeneous at the time of the emission of the CMB as well, and observable today through weak variations in the temperature of the CMB. It was the detection of these anisotropies that Smoot was working on in the late 1970s. He then proposed to NASA a project involving a satellite equipped with a detector that was similar to the one mounted on the U-2 but was more sensitive and not influenced by air pollution. The proposal was accepted and incorporated as one of the instruments of the satellite COBE, which cost $160 million. COBE was launched on November 18, 1989, after a delay owing to the destruction of the Space Shuttle Challenger. After more than two years of observation and analysis, the COBE research team announced on 23 April 1992 that the satellite had detected tiny fluctuations in the CMB, a breakthrough in the study of the early universe. The observations were "evidence for the birth of the universe" and led Smoot to say regarding the importance of his discovery that "if you're religious, it's like looking at God."

The success of COBE was the outcome of extensive teamwork involving more than 1,000 researchers, engineers and other participants. John Mather coordinated the entire process and also had primary responsibility for the experiment that revealed the blackbody form of the CMB measured by COBE. Smoot had the main responsibility of measuring the small variations in the temperature of the radiation.

Smoot collaborated with San Francisco Chronicle journalist Keay Davidson to write the general-audience book Wrinkles in Time, that chronicled his team's efforts. In the book The Very First Light, John Mather and John Boslough complement and broaden the COBE story, and suggest that Smoot violated team policy by leaking news of COBE's discoveries to the press before NASA's formal announcement, a leak that, to Mather, smacked of self-promotion and betrayal. Smoot eventually apologized for not following the agreed publicity plan and Mather said tensions eventually eased. Mather acknowledged that Smoot had "brought COBE worldwide publicity" the project might not normally have received.

Other projects

After COBE, Smoot took part in another experiment involving a stratospheric balloon, Millimeter Anisotropy eXperiment IMaging Array, which had improved angular resolution compared to COBE, and refined the measurements of the anisotropies of the CMB. Smoot has continued CMB observations and analysis and was a collaborator on the third generation CMB anisotropy observatory Planck satellite. He is also a collaborator of the design of the Supernova/Acceleration Probe, a satellite which is proposed to measure the properties of dark energy. He has also assisted in analyzing data from the Spitzer Space Telescope in connection with measuring far infrared background radiation. Smoot also was a leader in a group that launched the Mikhailo Lomonosov April 28, 2016.

Smoot is credited by Mickey Hart for inspiring the album Mysterium Tremendum, which is based, in part on "sounds" that can be extracted from the background signature of the Big Bang.

As of September 2019, Smoot is an artificial intelligence scientist for the GTA Foundation, whose business is storing genomic sequencing data and using it in scientific applications.

In November 2020, he joined Dead Sea Premier as head of research for their NUNA advanced technology anti-aging medical device development.

In April 2021, he joined the Xiaomi eco-system company Viomi as chief scientist for their AI-development.

In January 2023, George Fitzgerald Smoot III joined the National Council for Science and Technology under the President of the Republic of Kazakhstan.

It appears to me that if one wants to make progress in mathematics, one should study the masters and not the pupils. - Niels Henrik Abel.

Nothing is better than reading and gaining more and more knowledge - Stephen William Hawking.

Offline

#1634 2024-11-08 15:42:27

- Jai Ganesh

- Administrator

- Registered: 2005-06-28

- Posts: 52,998

Re: crème de la crème

2096) Roger D. Kornberg

Gist:

Life

Roger Kornberg was born in St Louis, Missouri in the United States. His parents were biochemists and his father, Arthur Kornberg, won the 1959 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine. Roger Kornberg studied chemistry at Harvard University in Cambridge, Massachusetts, and later completed his PhD in chemical physics at Stanford University, California, in 1972. After spending time at Cambridge, England, and at Harvard Medical School, Kornberg returned to Stanford in 1978, where he carried out the research that led to his Nobel Prize. Roger Kornberg is married with three children.

Work

An organism's genes are stored inside DNA molecules. From DNA, genes are transferred to RNA and then converted during protein formation. In the case of bacteria without cell nuclei, the process by which information stored in DNA is transferred to RNA was mapped during the 1960s. Concerning organisms with cells with delimited nuclei (eukaryotic cells), Roger Kornberg succeeded in mapping the process by studying yeast in the first decade of the new millennium. His contributions included determining the structure of the enzyme active in the process–RNA polymerase– and creating images of how the RNA molecule is constructed.

Summary

Roger D. Kornberg (born 1947, St. Louis, Mo., U.S.) is an American chemist, who won the Nobel Prize for Chemistry in 2006 for his research on the molecular basis of eukaryotic transcription.

Kornberg studied chemistry at Harvard University (B.S., 1967) and Stanford University (Ph.D., 1972). He later served on the faculty of Harvard Medical School (1976–78) before becoming a professor at Stanford in 1978.

Kornberg’s prizewinning research centred on the process by which DNA is converted into RNA. Known as transcription, it enables genetic information to be transferred to different parts of the body, a process that is crucial to an organism’s survival. Problems in transcription contribute to a number of illnesses, including cancer and heart disease. Kornberg’s studies revealed how transcription works at the molecular level for eukaryotes, a group of organisms that includes mammals.

Kornberg’s father, Arthur Kornberg, won the 1959 Nobel Prize for Physiology and Medicine. They are the sixth father-son tandem to win Nobel Prizes.

Details

Roger David Kornberg (born April 24, 1947) is an American biochemist and professor of structural biology at Stanford University School of Medicine. Kornberg was awarded the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 2006 for his studies of the process by which genetic information from DNA is copied to RNA, "the molecular basis of eukaryotic transcription."

Early life and education

Kornberg was born in St. Louis, Missouri, into a Jewish family, the eldest son of biochemist Arthur Kornberg, who won the Nobel Prize, and Sylvy Kornberg who was also a biochemist. He earned his bachelor's degree in chemistry from Harvard University in 1967 and his Ph.D. in chemical physics from Stanford in 1972 supervised by Harden M. McConnell.

Career

Kornberg became a postdoctoral research fellow at the Laboratory of Molecular Biology in Cambridge, England and then an Assistant Professor of Biological Chemistry at Harvard Medical School in 1976, before moving to his present position as Professor of Structural Biology at Stanford Medical School in 1978. Since 2004, Kornberg has been the editor of the Annual Review of Biochemistry. He serves on the Board of Directors of Annual Reviews.

Research

Kornberg identified the role of RNA polymerase II and other proteins in DNA transcription, creating three-dimensional images of the protein cluster using X-ray crystallography.

Kornberg and his research group have made several fundamental discoveries concerning the mechanisms and regulation of eukaryotic transcription. While a graduate student working with Harden McConnell at Stanford in the late 1960s, he discovered the "flip-flop" and lateral diffusion of phospholipids in bilayer membranes. Meanwhile, as a postdoctoral fellow working with Aaron Klug and Francis Crick at the MRC in the 1970s, Kornberg discovered the nucleosome as the basic protein complex packaging chromosomal DNA in the nucleus of eukaryotic cells (chromosomal DNA is often termed "chromatin" when it is bound to proteins in this manner). Within the nucleosome, Kornberg found that roughly 200 bp of DNA are wrapped around an octamer of histone proteins. With Yahli Lorch, Kornberg showed that a nucleosome on a promoter prevents the initiation of transcription, leading to the recognition of a functional role for the nucleosome, which serves as a general gene repressor.

Kornberg's research group at Stanford later succeeded in the development of a faithful transcription system from baker's yeast, a simple unicellular eukaryote, which they then used to isolate in a purified form all of the several dozen proteins required for the transcription process. Through the work of Kornberg and others, it has become clear that these protein components are remarkably conserved across the full spectrum of eukaryotes, from yeast to human cells.

Using this system, Kornberg made the major discovery that transmission of gene regulatory signals to the RNA polymerase machinery is accomplished by an additional protein complex that they dubbed Mediator. As noted by the Nobel Prize committee, "the great complexity of eukaryotic organisms is actually enabled by the fine interplay between tissue-specific substances, enhancers in the DNA and Mediator. The discovery of Mediator is therefore a true milestone in the understanding of the transcription process."

At the same time as Kornberg was pursuing these biochemical studies of the transcription process, he devoted two decades to the development of methods to visualize the atomic structure of RNA polymerase and its associated protein components. Initially, Kornberg took advantage of expertise with lipid membranes gained from his graduate studies to devise a technique for the formation of two-dimensional protein crystals on lipid bilayers. These 2D crystals could then be analyzed using electron microscopy to derive low-resolution images of the protein's structure. Eventually, Kornberg was able to use X-ray crystallography to solve the 3-dimensional structure of RNA polymerase at atomic resolution. He has recently extended these studies to obtain structural images of RNA polymerase associated with accessory proteins. Through these studies, Kornberg has created an actual picture of how transcription works at a molecular level. According to the Nobel Prize committee, "the truly revolutionary aspect of the picture Kornberg has created is that it captures the process of transcription in full flow. What we see is an RNA-strand being constructed, and hence the exact positions of the DNA, polymerase and RNA during this process."

Lipids membrane

As a graduate student at Stanford University, Kornberg's studied the rotation of phospholipids and defined for the first time the dynamics of lipids in the membrane. Kornberg called the movement of lipid from one leaflet to the other flip-flop because he had studied only a few years before electronic circuit elements called flip-flops. The term gave rise to the naming of proteins called flippases and floppases.

Industrial collaborations

Kornberg has served on the Scientific Advisory Boards of the following companies: Cocrystal Discovery, Inc (Chairman), ChromaDex Corporation (Chairman), StemRad, Ltd, Oplon Ltd (Chairman), and Pacific Biosciences. Kornberg has also been a director for the following companies: OphthaliX Inc., Protalix BioTherapeutics, Can-Fite BioPharma, Ltd, Simploud and Teva Pharmaceutical Industries, Ltd.

It appears to me that if one wants to make progress in mathematics, one should study the masters and not the pupils. - Niels Henrik Abel.

Nothing is better than reading and gaining more and more knowledge - Stephen William Hawking.

Offline

#1635 2024-11-09 15:46:49

- Jai Ganesh

- Administrator

- Registered: 2005-06-28

- Posts: 52,998

Re: crème de la crème

2097) Andrew Fire

Gist:

Work

RNA has multiple functions. Among these, messenger RNA carries genetic information from DNA to protein formation. RNA is often a single-stranded spiral, but also exists in double-stranded form. In 1998, Andrew Fire and Craig Mello discovered through their studies of the roundworm C. elegans a phenomenon dubbed RNA interference. In this phenomenon, double-stranded RNA blocks messenger RNA so that certain genetic information is not converted during protein formation. This silences these genes, i.e. renders them inactive. The phenomenon plays an important regulatory role within a genome.

Summary

Andrew Z. Fire (born April 27, 1959, Stanford, Calif., U.S.) is an American scientist, who was a corecipient, with Craig C. Mello, of the Nobel Prize for Physiology or Medicine in 2006 for discovering a mechanism for controlling the flow of genetic information.

Fire received a bachelor’s degree in mathematics (1978) from the University of California, Berkeley. He was subsequently accepted into the graduate biology program at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), where he worked with American molecular biologist Philip A. Sharp, who was awarded the 1993 Nobel Prize for Physiology or Medicine for his independent discovery of introns—long sections of DNA that do not encode proteins but are located within genes. Fire received a Ph.D. in biology from MIT in 1983 and then went to Cambridge, Eng., joining the Medical Research Council (MRC) Laboratory of Molecular Biology. At Cambridge, Fire worked with South African-born biologist Sydney Brenner and studied the genetic mechanisms that influence the early development of the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans.

In 1986 Fire joined the staff at the Carnegie Institution in Baltimore, Md., where he conducted his prizewinning research. Working with Mello, Fire helped discover RNA interference (RNAi), a mechanism in which genes are silenced by double-stranded RNA. Naturally occurring in plants, animals, and humans, RNAi regulates gene activity and helps defend against viral infection. The two men published their findings in 1998. Possible applications of RNAi include developing treatments for such diseases as AIDS, cancer, and hepatitis.

In 2003 Fire joined the faculty at Stanford University, taking professorships in pathology and genetics. His later research was concerned with understanding the mechanisms that enable cells to distinguish foreign DNA and RNA from the cells’ own genetic material. This work was aimed in part at elucidating the role of RNAi in silencing the activity of foreign genetic material introduced into cells by infectious agents. Fire also investigated the role of RNAi and other genetic mechanisms in enabling cells to adapt to changes that occur throughout an organism’s development.

In addition to the Nobel Prize, Fire received several other major awards during his career, including the Meyenburg Prize (2002) from the German Cancer Research Center, the Wiley Prize (2003), and the National Academy of Sciences Award in Molecular Biology (2003).

Details

Andrew Zachary Fire (born April 27, 1959) is an American biologist and professor of pathology and of genetics at the Stanford University School of Medicine. He was awarded the 2006 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine, along with Craig C. Mello, for the discovery of RNA interference (RNAi). This research was conducted at the Carnegie Institution of Washington and published in 1998.

Biography

Andrew Z Fire was born in Palo Alto, California and raised in Sunnyvale, California in a Jewish family. He graduated from Fremont High School. He attended the University of California, Berkeley for his undergraduate degree, where he received a B.A. in mathematics in 1978 at the age of 19. He then proceeded to the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, where he received a Ph.D. in biology in 1983 under the mentorship of Nobel laureate geneticist Phillip Sharp.

Fire moved to Cambridge, England, as a Helen Hay Whitney Postdoctoral Fellow. He became a member of the MRC Laboratory of Molecular Biology group headed by Nobel laureate biologist Sydney Brenner.

From 1986 to 2003, Fire was a staff member of the Carnegie Institution of Washington’s Department of Embryology in Baltimore, Maryland. The initial work on double stranded RNA as a trigger of gene silencing was published while Fire and his group were at the Carnegie Labs. Fire became an adjunct professor in the Department of Biology at Johns Hopkins University in 1989 and joined the Stanford faculty in 2003. Throughout his career, Fire has been supported by research grants from the U.S. National Institutes of Health.

Fire is a member of the National Academy of Sciences and the American Academy of Arts and Sciences. He also serves on the Board of Scientific Counselors and the National Center for Biotechnology, National Institutes of Health.

Nobel Prize

In 2006, Fire and Craig Mello shared the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for work first published in 1998 in the journal Nature. Fire and Mello, along with colleagues SiQun Xu, Mary Montgomery, Stephen Kostas, and Sam Driver, reported that tiny snippets of double-stranded RNA (dsRNA) effectively shut down specific genes, driving the destruction of messenger RNA (mRNA) with sequences matching the dsRNA. As a result, the mRNA cannot be translated into protein. Fire and Mello found that dsRNA was much more effective in gene silencing than the previously described method of RNA interference with single-stranded RNA. Because only small numbers of dsRNA molecules were required for the observed effect, Fire and Mello proposed that a catalytic process was involved. This hypothesis was confirmed by subsequent research.

The Nobel Prize citation, issued by Sweden's Karolinska Institute, said: "This year's Nobel Laureates have discovered a fundamental mechanism for controlling the flow of genetic information." The British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC) quoted Nick Hastie, director of the Medical Research Council's Human Genetics Unit, on the scope and implications of the research:

It is very unusual for a piece of work to completely revolutionise the whole way we think about biological processes and regulation, but this has opened up a whole new field in biology.

It appears to me that if one wants to make progress in mathematics, one should study the masters and not the pupils. - Niels Henrik Abel.

Nothing is better than reading and gaining more and more knowledge - Stephen William Hawking.

Offline

#1636 2024-11-10 15:31:09

- Jai Ganesh

- Administrator

- Registered: 2005-06-28

- Posts: 52,998

Re: crème de la crème

2098) Craig Mello

Gist:

Work

RNA has multiple functions. Among these, messenger RNA carries genetic information from DNA to protein formation. RNA is often a single-stranded spiral, but also exists in double-stranded form. In 1998, Craig Mello and Andrew Fire discovered through their studies of the roundworm C. elegans a phenomenon dubbed RNA interference. In this phenomenon, double-stranded RNA blocks messenger RNA so that certain genetic information is not converted during protein formation. This silences these genes, i.e. renders them inactive. The phenomenon plays an important regulatory role within a genome.

Summary

Craig C. Mello (born Oct. 18, 1960, New Haven, Conn., U.S.) is an American scientist, who was a corecipient, with Andrew Z. Fire, of the Nobel Prize for Physiology or Medicine in 2006 for discovering RNA interference (RNAi), a mechanism that regulates gene activity.

Mello grew up in northern Virginia, and, as a young boy, he developed an intense curiosity in the living world. His curiosity was largely influenced by his father, James Mello, a paleontologist who had served as the associate director of the National Museum of Natural History at the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, D.C. Mello was intrigued by fundamental concepts such as evolution. He felt that these concepts encouraged humans to ask questions about the world around them, a belief that led to his rejection of religion at a young age. Mello attended Brown University in Providence, Rhode Island, studying biochemistry and molecular biology and receiving a B.S. degree in 1982. He began his graduate studies in biology at the University of Colorado in Boulder, where he worked in the laboratory of American molecular biologist David Hirsh, who was investigating the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans. While conducting research in Hirsh’s lab, Mello was introduced to American molecular biologist Dan Stinchcomb. When Stinchcomb decided to move to Harvard University in Cambridge, Mass., to start his own research laboratory, Mello decided to follow him. At Harvard Mello became deeply involved in research on C. elegans, and his studies led him to American scientist Andrew Z. Fire, who was working at the Carnegie Institution for Science in Baltimore, Md. Both Mello and Fire were working to find a way to insert DNA into C. elegans, a process known as DNA transformation. After exchanging ideas and elaborating on one another’s experiments, they successfully developed a procedure for DNA transformation in nematodes. In 1990, following the completion of his thesis, C. elegans DNA Transformation, Mello graduated from Harvard with a Ph.D. in biology.

Mello worked at the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center in Seattle, Wash., from 1990 to 1994. He continued studying C. elegans, though his focus had shifted to identifying genes involved in regulating nematode development. In 1994 Mello joined the faculty at the University of Massachusetts Medical School. He became interested in an RNA injection technique used to silence genes. Silencing genes in C. elegans enabled Mello to identify the functions of the genes he had discovered while working in Seattle. He soon found that some nematode embryos that had been injected with RNA to silence certain genes were able to transmit the silencing effect to their offspring. Mello and Fire worked in collaboration to uncover the cellular mechanism driving this active silencing phenomenon and discovered that the genes were being silenced by double-stranded RNA. Known as RNAi, this mechanism regulates gene activity and helps defend against viral infection. In 1998 they published their findings, for which they later received the Nobel Prize. RNAi has proved a valuable research tool, enabling scientists to block genes in order to uncover the basic functions and roles of genes in disease. RNAi can also be used to develop new treatments for a number of diseases, including AIDS, cancer, and hepatitis. Following the RNAi publication, Mello focused his research on applying the silencing technique to the study of embryonic cell differentiation in C. elegans. In 2000 Mello was awarded the title of Howard Hughes Medical Investigator because of his significant contributions to science.

Details

Craig Cameron Mello (born October 18, 1960) is an American biologist and professor of molecular medicine at the University of Massachusetts Medical School in Worcester, Massachusetts. He was awarded the 2006 Nobel Prize for Physiology or Medicine, along with Andrew Z. Fire, for the discovery of RNA interference. This research was conducted at the Carnegie Institution of Washington and published in 1998. Mello has been a Howard Hughes Medical Institute investigator since 2000.

Early life

Mello was born in New Haven, Connecticut on October 18, 1960. He was the third child of James and Sally Mello. His father, James Mello, was a paleontologist and his mother, Sally Mello, was an artist. His paternal grandparents immigrated to the US from the Portuguese islands of Azores. His parents met while attending Brown University and were the first children in their respective families to attend college. His grandparents on both sides withdrew from school as teenagers to work for their families. James Mello completed his Ph.D. in paleontology from Yale University in 1962. The Mello family moved to Falls Church in northern Virginia so that James could take a position with the United States Geological Survey (USGS) in Washington, DC. He was raised as Roman Catholic.