Math Is Fun Forum

You are not logged in.

- Topics: Active | Unanswered

#126 2018-05-01 01:11:58

- Jai Ganesh

- Administrator

- Registered: 2005-06-28

- Posts: 52,612

Re: Miscellany

110) Kiwi

Kiwi, any of five species of flightless birds belonging to the genus Apteryx and found in New Zealand. The name is a Maori word referring to the shrill call of the male. Kiwis are grayish brown birds the size of a chicken. They are related to the extinct moas. Kiwis are unusual in many respects: the vestigial wings are hidden within the plumage; the nostrils are at the tip (rather than the base) of the long, flexible bill; the feathers, which have no aftershafts, are soft and hairlike; the legs are stout and muscular; and each of the four toes has a large claw. The eyes are small and inefficient in full daylight, the ear openings are large and well developed, and very long bristles (perhaps tactile) occur at the base of the bill.

Dwelling in forests, kiwis sleep by day in burrows and forage for food—worms, insects and their larvae, and berries—by night. They can run swiftly when required; when trapped they use their claws in defense.

One or two large white eggs—up to 450 g (1 pound) in weight—are laid in a burrow and are incubated by the male for about 80 days. The egg is, relative to the size of the bird, the largest of any living species. The chick hatches fully feathered and with its eyes open; it does not eat for about a week.

Although no longer abundant, kiwis appear to be in no danger of extinction and may even be gradually adapting to semipastoral land.

The genus Apteryx forms the family Apterygidae, order Apterygiformes. Five species of kiwis are recognized: the tokoeka kiwi (A. australis), which includes the Haast tokoeka, Stewart Island tokoeka, Southern Fiordland tokoeka, and the Northern Fiordland tokoeka; the little spotted kiwi (A. oweni); the great spotted kiwi (A. haasti); the Okarito brown kiwi (A. rowi), also called the Rowi kiwi; and the brown kiwi (A. mantelli), also called the North Island brown kiwi.

It appears to me that if one wants to make progress in mathematics, one should study the masters and not the pupils. - Niels Henrik Abel.

Nothing is better than reading and gaining more and more knowledge - Stephen William Hawking.

Online

#127 2018-05-03 03:53:13

- Jai Ganesh

- Administrator

- Registered: 2005-06-28

- Posts: 52,612

Re: Miscellany

111) Mutation

Mutation, an alteration in the genetic material (the genome) of a cell of a living organism or of a virus that is more or less permanent and that can be transmitted to the cell’s or the virus’s descendants. (The genomes of organisms are all composed of DNA, whereas viral genomes can be of DNA or RNA; see heredity: The physical basis of heredity.) Mutation in the DNA of a body cell of a multicellular organism (somatic mutation) may be transmitted to descendant cells by DNA replication and hence result in a sector or patch of cells having abnormal function, an example being cancer. Mutations in egg or sperm cells (germinal mutations) may result in an individual offspring all of whose cells carry the mutation, which often confers some serious malfunction, as in the case of a human genetic disease such as cystic fibrosis. Mutations result either from accidents during the normal chemical transactions of DNA, often during replication, or from exposure to high-energy electromagnetic radiation (e.g., ultraviolet light or X-rays) or particle radiation or to highly reactive chemicals in the environment. Because mutations are random changes, they are expected to be mostly deleterious, but some may be beneficial in certain environments. In general, mutation is the main source of genetic variation, which is the raw material for evolution by natural selection.

The genome is composed of one to several long molecules of DNA, and mutation can occur potentially anywhere on these molecules at any time. The most serious changes take place in the functional units of DNA, the genes. A mutated form of a gene is called a mutant allele. A gene is typically composed of a regulatory region, which is responsible for turning the gene’s transcription on and off at the appropriate times during development, and a coding region, which carries the genetic code for the structure of a functional molecule, generally a protein. A protein is a chain of usually several hundred amino acids. Cells make 20 common amino acids, and it is the unique number and sequence of these that give a protein its specific function. Each amino acid is encoded by a unique sequence, or codon, of three of the four possible base pairs in the DNA (A–T, T–A, G–C, and C–G, the individual letters referring to the four nitrogenous bases adenine, thymine, guanine, and cytosine). Hence, a mutation that changes DNA sequence can change amino acid sequence and in this way potentially reduce or inactivate a protein’s function. A change in the DNA sequence of a gene’s regulatory region can adversely affect the timing and availability of the gene’s protein and also lead to serious cellular malfunction. On the other hand, many mutations are silent, showing no obvious effect at the functional level. Some silent mutations are in the DNA between genes, or they are of a type that results in no significant amino acid changes.

Mutations are of several types. Changes within genes are called point mutations. The simplest kinds are changes to single base pairs, called base-pair substitutions. Many of these substitute an incorrect amino acid in the corresponding position in the encoded protein, and of these a large proportion result in altered protein function. Some base-pair substitutions produce a stop codon. Normally, when a stop codon occurs at the end of a gene, it stops protein synthesis, but, when it occurs in an abnormal position, it can result in a truncated and nonfunctional protein. Another type of simple change, the deletion or insertion of single base pairs, generally has a profound effect on the protein because the protein’s synthesis, which is carried out by the reading of triplet codons in a linear fashion from one end of the gene to the other, is thrown off. This change leads to a frameshift in reading the gene such that all amino acids are incorrect from the mutation onward. More-complex combinations of base substitutions, insertions, and deletions can also be observed in some mutant genes.

Mutations that span more than one gene are called chromosomal mutations because they affect the structure, function, and inheritance of whole DNA molecules (microscopically visible in a coiled state as chromosomes). Often these chromosome mutations result from one or more coincident breaks in the DNA molecules of the genome (possibly from exposure to energetic radiation), followed in some cases by faulty rejoining. Some outcomes are large-scale deletions, duplications, inversions, and translocations. In a diploid species (a species, such as human beings, that has a double set of chromosomes in the nucleus of each cell), deletions and duplications alter gene balance and often result in abnormality. Inversions and translocations involve no loss or gain and are functionally normal unless a break occurs within a gene. However, at meiosis (the specialized nuclear divisions that take place during the production of gametes—i.e., eggs and sperm), faulty pairing of an inverted or translocated chromosome set with a normal set can result in gametes and hence progeny with duplications and deletions.

Loss or gain of whole chromosomes results in a condition called aneuploidy. One familiar result of aneuploidy is Down syndrome, a chromosomal disorder in which humans are born with an extra chromosome 21 (and hence bear three copies of that chromosome instead of the usual two). Another type of chromosome mutation is the gain or loss of whole chromosome sets. Gain of sets results in polyploidy—that is, the presence of three, four, or more chromosome sets instead of the usual two. Polyploidy has been a significant force in the evolution of new species of plants and animals.

Most genomes contain mobile DNA elements that move from one location to another. The movement of these elements can cause mutation, either because the element arrives in some crucial location, such as within a gene, or because it promotes large-scale chromosome mutations via recombination between pairs of mobile elements in different locations.

At the level of whole populations of organisms, mutation can be viewed as a constantly dripping faucet introducing mutant alleles into the population, a concept described as mutational pressure. The rate of mutation differs for different genes and organisms. In RNA viruses, such as the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), replication of the genome takes place within the host cell using a mechanism that is prone to error. Hence, mutation rates in such viruses are high. In general, however, the fate of individual mutant alleles is never certain. Most are eliminated by chance. In some cases a mutant allele can increase in frequency by chance, and then individuals expressing the allele can be subject to selection, either positive or negative. Hence, for any one gene the frequency of a mutant allele in a population is determined by a combination of mutational pressure, selection, and chance.

It appears to me that if one wants to make progress in mathematics, one should study the masters and not the pupils. - Niels Henrik Abel.

Nothing is better than reading and gaining more and more knowledge - Stephen William Hawking.

Online

#128 2018-05-05 00:59:11

- Jai Ganesh

- Administrator

- Registered: 2005-06-28

- Posts: 52,612

Re: Miscellany

112) Vitamin C

Vitamin C, also called ascorbic acid, water-soluble, carbohydrate-like substance that is involved in certain metabolic processes of animals. Although most animals can synthesize vitamin C, it is necessary in the diet of some, including humans and other primates, in order to prevent scurvy, a disease characterized by soreness and stiffness of the joints and lower extremities, rigidity, swollen and bloody gums, and hemorrhages in the tissues of the body. First isolated in 1928, vitamin C was identified as the curative agent for scurvy in 1932.

Vitamin C is essential for the synthesis of collagen, a protein important in the formation of connective tissue and in wound healing. It acts as an antioxidant, protecting against damage by reactive molecules called free radicals. The vitamin also helps in stimulating the immune system. It has been shown in animal trials that vitamin C has some anticarcinogenic activity.

Relatively large amounts of vitamin C are required—for instance, an adult man is said to need about 70 mg (1 mg = 0.001 gram) per day. Citrus fruits and fresh vegetables are the best dietary sources of the vitamin. Because vitamin C is easily destroyed by reactions with oxygen, especially in neutral or alkaline solution or at elevated temperatures, it is difficult to preserve in foods. The vitamin is added to certain fruits to prevent browning.

It appears to me that if one wants to make progress in mathematics, one should study the masters and not the pupils. - Niels Henrik Abel.

Nothing is better than reading and gaining more and more knowledge - Stephen William Hawking.

Online

#129 2018-05-07 02:20:14

- Jai Ganesh

- Administrator

- Registered: 2005-06-28

- Posts: 52,612

Re: Miscellany

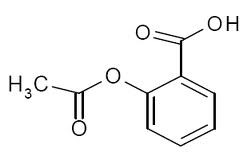

113) Aspirin

Aspirin, also called acetylsalicylic acid, derivative of salicylic acid that is a mild nonnarcotic analgesic useful in the relief of headache and muscle and joint aches. Aspirin is effective in reducing fever, inflammation, and swelling and thus has been used for treatment of rheumatoid arthritis, rheumatic fever, and mild infection. In these instances, aspirin generally acts on the symptoms of disease and does not modify or shorten the duration of a disease. However, because of its ability to inhibit the production of blood platelet aggregates (which may cut off the blood supply to regions of the heart or brain), it has also been used as an anticoagulant in the treatment of such conditions as unstable angina or following a minor stroke or heart attack.

Aspirin is sometimes used as a preventive agent for certain diseases. For example, daily intake of low-dose aspirin (75–300 mg) can reduce the risk of heart attack or stroke in high-risk individuals. Studies have also found that long-term use of low-dose aspirin can lower the risk of colon cancer in some persons and is associated with a reduced risk of death from several types of cancer, including certain forms of colon cancer as well as lung cancer and esophageal cancer.

Aspirin acts by inhibiting the production of prostaglandins, body chemicals that are necessary for blood clotting and are noted for sensitizing nerve endings to pain. The use of aspirin has been known to cause allergic reaction and gastrointestinal problems in some people. It has also been linked to the development in children (primarily those 2 to 16 years old) of Reye syndrome, an acute disorder of the liver and central nervous system that may follow viral infections such as influenza and chicken pox, and to the development of age-related macular degeneration (a blinding disorder) in some persons who use the drug regularly over many years. Like almost all drugs, aspirin is to be avoided during pregnancy.

It appears to me that if one wants to make progress in mathematics, one should study the masters and not the pupils. - Niels Henrik Abel.

Nothing is better than reading and gaining more and more knowledge - Stephen William Hawking.

Online

#130 2018-05-08 23:23:35

- Jai Ganesh

- Administrator

- Registered: 2005-06-28

- Posts: 52,612

Re: Miscellany

114) Anaconda

Anaconda, (genus Eunectes), either of two species of constricting, water-loving snakes found in tropical South America. The green anaconda (Eunectes murinus), also called the giant anaconda, sucuri, or water kamudi, is an olive-coloured snake with alternating oval-shaped black spots. The yellow, or southern, anaconda (E. notaeus) is much smaller and has pairs of overlapping spots.

Green anacondas live along tropical waters east of the Andes Mountains and on the Caribbean island of Trinidad. The green anaconda is the largest snake in the world. Although anacondas and pythons both have been reliably measured at over 9 metres (30 feet) long, anacondas have been reported to measure over 10 metres (33 feet) and are much more heavily built. Most individuals, however, do not exceed 5 metres (16 feet).

Green anacondas lie in the water (generally at night) to ambush caimans and mammals such as capybara, deer, tapirs, and peccaries that come to drink. An anaconda seizes a large animal by the neck and almost instantly throws its coils around it, killing it by constriction. Anacondas kill smaller prey, such as small turtles and diving birds, with the mouth and sharp backward-pointing teeth alone. Kills made onshore are often dragged into the water, perhaps to avoid attracting jaguars and to ward off biting ants attracted to the carcass. In the wild, green anacondas are not particularly aggressive. In Venezuela, they are captured easily during the day by herpetologists who, in small groups, merely walk up to the snakes and carry them off.

Green anacondas mate in or very near the water. After nine months, a female gives live birth to 14–82 babies, each more than 62 cm (24 inches) in length. The young grow rapidly, attaining almost 3 metres (10 feet) by age three.

Anacondas are members of the boa family (Boidae).

It appears to me that if one wants to make progress in mathematics, one should study the masters and not the pupils. - Niels Henrik Abel.

Nothing is better than reading and gaining more and more knowledge - Stephen William Hawking.

Online

#131 2018-05-10 01:33:44

- Jai Ganesh

- Administrator

- Registered: 2005-06-28

- Posts: 52,612

Re: Miscellany

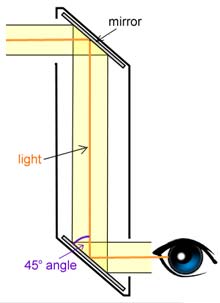

115) Periscope

Periscope, optical instrument used in land and sea warfare, submarine navigation, and elsewhere to enable an observer to see his surroundings while remaining under cover, behind armour, or submerged.

A periscope includes two mirrors or reflecting prisms to change the direction of the light coming from the scene observed: the first deflects it down through a vertical tube, the second diverts it horizontally so that the scene can be viewed conveniently. Frequently there is a telescopic optical system that provides magnification, gives as wide an arc of vision as possible, and includes a crossline or reticle pattern to establish the line of sight to the object under observation. There may also be devices for estimating the range and course of the target in military applications and for photographing through the periscope.

The simplest type of periscope consists of a tube at the ends of which are two mirrors, parallel to each other but at 45° to the axis of the tube. This device produces no magnification and does not give a crossline image. The arc of vision is limited by the simple geometry of the tube: the longer or narrower the tube, the smaller the field of view. Periscopes of this type were widely used in World War II in tanks and other armoured vehicles as observation devices for the driver, gunner, and commander. When fitted with a small, auxiliary gunsight telescope, the tank periscope can also be used in pointing and firing the guns. By employing tubes of rectangular cross section, wide, horizontal fields of view can be obtained.

It appears to me that if one wants to make progress in mathematics, one should study the masters and not the pupils. - Niels Henrik Abel.

Nothing is better than reading and gaining more and more knowledge - Stephen William Hawking.

Online

#132 2018-05-10 15:53:30

- Jai Ganesh

- Administrator

- Registered: 2005-06-28

- Posts: 52,612

Re: Miscellany

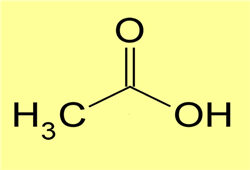

116) Acetic Acid

Acetic acid (CH3COOH), also called ethanoic acid, the most important of the carboxylic acids. A dilute (approximately 5 percent by volume) solution of acetic acid produced by fermentation and oxidation of natural carbohydrates is called vinegar; a salt, ester, or acylal of acetic acid is called acetate. Industrially, acetic acid is used in the preparation of metal acetates, used in some printing processes; vinyl acetate, employed in the production of plastics; cellulose acetate, used in making photographic films and textiles; and volatile organic esters (such as ethyl and butyl acetates), widely used as solvents for resins, paints, and lacquers. Biologically, acetic acid is an important metabolic intermediate, and it occurs naturally in body fluids and in plant juices.

Acetic acid has been prepared on an industrial scale by air oxidation of acetaldehyde, by oxidation of ethanol (ethyl alcohol), and by oxidation of butane and butene. Today acetic acid is manufactured by a process developed by the chemical company Monsanto in the 1960s; it involves a rhodium-iodine catalyzed carbonylation of methanol (methyl alcohol).

Pure acetic acid, often called glacial acetic acid, is a corrosive, colourless liquid (boiling point 117.9 °C [244.2 °F]; melting point 16.6 °C [61.9 °F]) that is completely miscible with water.

It appears to me that if one wants to make progress in mathematics, one should study the masters and not the pupils. - Niels Henrik Abel.

Nothing is better than reading and gaining more and more knowledge - Stephen William Hawking.

Online

#133 2018-05-12 01:03:48

- Jai Ganesh

- Administrator

- Registered: 2005-06-28

- Posts: 52,612

Re: Miscellany

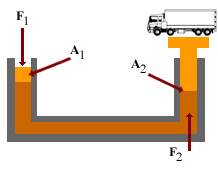

117) Pascal's Law

Pascal’s principle, also called Pascal’s law, in fluid (gas or liquid) mechanics, statement that, in a fluid at rest in a closed container, a pressure change in one part is transmitted without loss to every portion of the fluid and to the walls of the container. The principle was first enunciated by the French scientist Blaise Pascal.

Pressure is equal to the force divided by the area on which it acts. According to Pascal’s principle, in a hydraulic system a pressure exerted on a piston produces an equal increase in pressure on another piston in the system. If the second piston has an area 10 times that of the first, the force on the second piston is 10 times greater, though the pressure is the same as that on the first piston. This effect is exemplified by the hydraulic press, based on Pascal’s principle, which is used in such applications as hydraulic brakes.

Pascal also discovered that the pressure at a point in a fluid at rest is the same in all directions; the pressure would be the same on all planes passing through a specific point. This fact is also known as Pascal’s principle, or Pascal’s law.

It appears to me that if one wants to make progress in mathematics, one should study the masters and not the pupils. - Niels Henrik Abel.

Nothing is better than reading and gaining more and more knowledge - Stephen William Hawking.

Online

#134 2018-05-14 00:50:46

- Jai Ganesh

- Administrator

- Registered: 2005-06-28

- Posts: 52,612

Re: Miscellany

118) Benzoic Acid

Benzoic acid, a white, crystalline organic compound belonging to the family of carboxylic acids, widely used as a food preservative and in the manufacture of various cosmetics, dyes, plastics, and insect repellents.

First described in the 16th century, benzoic acid exists in many plants; it makes up about 20 percent of gum benzoin, a vegetable resin. It was first prepared synthetically about 1860 from compounds derived from coal tar. It is commercially manufactured by the chemical reaction of toluene (a hydrocarbon obtained from petroleum) with oxygen at temperatures around 200° C (about 400° F) in the presence of cobalt and manganese salts as catalysts. Pure benzoic acid melts at 122° C (252° F) and is very slightly soluble in water.

Among the derivatives of benzoic acid are sodium benzoate, a salt used as a food preservative; benzyl benzoate, an ester used as a miticide; and benzoyl peroxide, used in bleaching flour and in initiating chemical reactions for preparing certain plastics.

It appears to me that if one wants to make progress in mathematics, one should study the masters and not the pupils. - Niels Henrik Abel.

Nothing is better than reading and gaining more and more knowledge - Stephen William Hawking.

Online

#135 2018-05-16 00:54:28

- Jai Ganesh

- Administrator

- Registered: 2005-06-28

- Posts: 52,612

Re: Miscellany

119) Basil

Basil, (Ocimum basilicum), also called sweet basil, annual herb of the mint family (Lamiaceae), grown for its aromatic leaves. Basil is likely native to India and is widely grown as a kitchen herb. The leaves are used fresh or dried to flavour meats, fish, salads, and sauces; basil tea is a stimulant.

Basil leaves are glossy and oval-shaped, with smooth or slightly toothed edges that typically cup slightly; the leaves are arranged oppositely along the square stems. The small flowers are borne in terminal clusters and range in colour from white to magenta. The plant is extremely frost-sensitive and grows best in warm climates. Basil is susceptible to Fusarium wilt, blight, and downy mildew, especially when grown in humid conditions.

A number of varieties are used in commerce, including the small-leaf common basil, the larger leaf Italian basil, and the large lettuce-leaf basil. Thai basil (O. basilicum var. thyrsiflora) and the related holy basil (O. tenuiflorum) and lemon basil (O. ×citriodorum) are common in Asian cuisine. The dried large-leaf varieties have a fragrant aroma faintly reminiscent of anise and a warm, sweet, aromatic, mildly pungent flavour. The dried leaves of the common basil are less fragrant and more pungent in flavour.

The essential oil content is 0.1 percent, the principal components of which are methyl chavicol and d-linalool.

It appears to me that if one wants to make progress in mathematics, one should study the masters and not the pupils. - Niels Henrik Abel.

Nothing is better than reading and gaining more and more knowledge - Stephen William Hawking.

Online

#136 2018-05-18 01:25:21

- Jai Ganesh

- Administrator

- Registered: 2005-06-28

- Posts: 52,612

Re: Miscellany

120) Ear bone

Ear bone, also called Auditory Ossicle, any of the three tiny bones in the middle ear of all mammals. These are the malleus, or hammer, the incus, or anvil, and the stapes, or stirrup. Together they form a short chain that crosses the middle ear and transmits vibrations caused by sound waves from the eardrum membrane to the liquid of the inner ear. The malleus resembles a club more than a hammer, whereas the incus looks like a premolar tooth with an extensive root system. The stapes does closely resemble a stirrup. The top or head of the malleus and the body of the incus are held together by a tightly fitting joint and are seated in the attic, or upper portion, of the eardrum cavity. The handle of the malleus adheres to the upper half of the drum membrane. Three small ligaments hold the head of the malleus, and a fourth attaches a projection (called the short process) from the incus to a slight depression in the back wall of the cavity. The long process of the incus is bent near the lower end and carries a small knoblike bone that is jointed loosely to the head of the stapes—the third and smallest of the ossicles. The stapes lies in a horizontal position at right angles with the long process of the incus. There are two openings in the wall of the bony labyrinth and the stapes footplate fits perfectly in one of these openings—an oval-shaped window, where it is held in place by yet another ligament called the annular ligament.

There are two tiny muscles in the middle ear, which serve to alter the tension on the ear bones and thus the intensity (degree of loudness) of sounds. One, the tensor tympani, is attached to the handle of the malleus (itself attached to the eardrum membrane) and by its contraction tends to draw the malleus inward, thus increasing drum membrane tension. The second, called stapedius, tends to pull the footplate of the stapes out of the oval window. This is accomplished by tipping the stirrup, or stapes, backward.

It appears to me that if one wants to make progress in mathematics, one should study the masters and not the pupils. - Niels Henrik Abel.

Nothing is better than reading and gaining more and more knowledge - Stephen William Hawking.

Online

#137 2018-05-20 00:50:39

- Jai Ganesh

- Administrator

- Registered: 2005-06-28

- Posts: 52,612

Re: Miscellany

121) Spirogyra

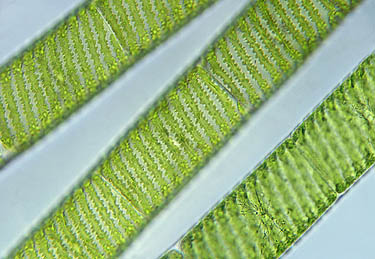

Spirogyra, (genus Spirogyra), any member of a genus of some 400 species of free-floating green algae (division Chlorophyta) found in freshwater environments around the world. Named for their beautiful spiral chloroplasts, spirogyras are filamentous algae that consist of thin unbranched chains of cylindrical cells. They can form masses that float near the surface of streams and ponds, buoyed by oxygen bubbles released during photosynthesis. They are commonly used in laboratory demonstrations.

Each cell of the filaments features a large central vacuole, within which the nucleus is suspended by fine strands of cytoplasm. The chloroplasts form a spiral around the vacuole and have specialized bodies known as pyrenoids that store starch. The cell wall consists of an inner layer of cellulose and an outer layer of pectin, which is responsible for the slippery texture of the algae.

Spirogyra species can reproduce both sexually and asexually. Asexual, or vegetative, reproduction occurs by simple fragmentation of the filaments. Sexual reproduction occurs by a process known as conjugation, in which cells of two filaments lying side by side are joined by outgrowths called conjugation tubes. This allows the contents of one cell to completely pass into and fuse with the contents of the other. The resulting fused cell (zygote) becomes surrounded by a thick wall and overwinters, while the vegetative filaments die.

It appears to me that if one wants to make progress in mathematics, one should study the masters and not the pupils. - Niels Henrik Abel.

Nothing is better than reading and gaining more and more knowledge - Stephen William Hawking.

Online

#138 2018-05-22 00:12:36

- Jai Ganesh

- Administrator

- Registered: 2005-06-28

- Posts: 52,612

Re: Miscellany

122) Hooke's Law

Hooke’s law, law of elasticity discovered by the English scientist Robert Hooke in 1660, which states that, for relatively small deformations of an object, the displacement or size of the deformation is directly proportional to the deforming force or load. Under these conditions the object returns to its original shape and size upon removal of the load. Elastic behaviour of solids according to Hooke’s law can be explained by the fact that small displacements of their constituent molecules, atoms, or ions from normal positions is also proportional to the force that causes the displacement.

The deforming force may be applied to a solid by stretching, compressing, squeezing, bending, or twisting. Thus, a metal wire exhibits elastic behaviour according to Hooke’s law because the small increase in its length when stretched by an applied force doubles each time the force is doubled. Mathematically, Hooke’s law states that the applied force F equals a constant k times the displacement or change in length x, or F = kx. The value of k depends not only on the kind of elastic material under consideration but also on its dimensions and shape.

At relatively large values of applied force, the deformation of the elastic material is often larger than expected on the basis of Hooke’s law, even though the material remains elastic and returns to its original shape and size after removal of the force. Hooke’s law describes the elastic properties of materials only in the range in which the force and displacement are proportional. Sometimes Hooke’s law is formulated as F = −kx. In this expression F no longer means the applied force but rather means the equal and oppositely directed restoring force that causes elastic materials to return to their original dimensions.

Hooke’s law may also be expressed in terms of stress and strain. Stress is the force on unit areas within a material that develops as a result of the externally applied force. Strain is the relative deformation produced by stress. For relatively small stresses, stress is proportional to strain.

It appears to me that if one wants to make progress in mathematics, one should study the masters and not the pupils. - Niels Henrik Abel.

Nothing is better than reading and gaining more and more knowledge - Stephen William Hawking.

Online

#139 2018-05-23 23:45:13

- Jai Ganesh

- Administrator

- Registered: 2005-06-28

- Posts: 52,612

Re: Miscellany

123) Hibiscus

Hibiscus, any of numerous species of herbs, shrubs, and trees constituting the genus Hibiscus, in the family Malvaceae, and native to warm temperate and tropical regions. Several are cultivated as ornamentals for their showy flowers.

The tropical Chinese hibiscus, or China rose (H. rosa-sinensis), which may reach a height of 4.5 metres (15 feet), rarely exceeds 2 metres (6.5 feet) in cultivation. It is grown for its large, somewhat bell-shaped blossoms. Cultivated varieties have red, white, yellow, or orange flowers. The East African hibiscus (H. schizopetalus), a drooping shrub with deeply lobed red petals, is often grown in hanging baskets indoors. Other members of the genus Hibiscus include the fibre plants mahoe and kenaf, okra, musk mallow, rose of Sharon, and many flowering plants known by the common name mallow.

Hibiscus now includes the former genus Abutilon, containing more than 100 species of herbaceous plants and partly woody shrubs native to tropical and warm temperate areas. Several species are used as houseplants and in gardens for their white to deep orange, usually nodding, five-petaled blossoms. H. hybridum, sometimes called Chinese lantern, is planted outdoors in warm regions and grown in greenhouses elsewhere. The trailing abutilon (H. megapotamicum), often grown as a hanging plant, is noted for its nodding, yellowish orange, closed flowers; it has a handsome variegated-leaf variety. H. pictum, a shrub reaching a height of 4.5 metres (15 feet), often called parlor, or flowering, maple, is grown as a houseplant. An important fibre plant in China is H. theophrastii, called China jute; it is a very serious field weed in the United States, where it is called velvetleaf or Indian mallow.

It appears to me that if one wants to make progress in mathematics, one should study the masters and not the pupils. - Niels Henrik Abel.

Nothing is better than reading and gaining more and more knowledge - Stephen William Hawking.

Online

#140 2018-05-24 18:08:47

- Jai Ganesh

- Administrator

- Registered: 2005-06-28

- Posts: 52,612

Re: Miscellany

124) Hydrometer

Hydrometer, device for measuring some characteristics of a liquid, such as its density (weight per unit volume) or specific gravity (weight per unit volume compared with water). The device consists essentially of a weighted, sealed, long-necked glass bulb that is immersed in the liquid being measured; the depth of flotation gives an indication of liquid density, and the neck can be calibrated to read density, specific gravity, or some other related characteristic.

In practice, the floating glass bulb is usually inserted into a cylindrical glass tube equipped with a rubber ball at the top end for sucking liquid into the tube. Immersion depth of the bulb is calibrated to read the desired characteristic. A typical instrument is the storage-battery hydrometer, by means of which the specific gravity of the battery liquid can be measured and the condition of the battery determined. Another instrument is the radiator hydrometer, in which the float is calibrated in terms of the freezing point of the radiator solution. Others may be calibrated in terms of “proof” of an alcohol solution or in terms of the percentage of sugar in a sugar solution.

The Baumé hydrometer, named for the French chemist Antoine Baumé, is calibrated to measure specific gravity on evenly spaced scales; one scale is for liquids heavier than water, and the other is for liquids lighter than water.

It appears to me that if one wants to make progress in mathematics, one should study the masters and not the pupils. - Niels Henrik Abel.

Nothing is better than reading and gaining more and more knowledge - Stephen William Hawking.

Online

#141 2018-05-25 00:22:25

- Jai Ganesh

- Administrator

- Registered: 2005-06-28

- Posts: 52,612

Re: Miscellany

125) Mercury

Mercury (Hg), also called quicksilver, chemical element, liquid metal of Group 12 (IIb, or zinc group) of the periodic table.

Properties, Uses, And Occurrence

Mercury was known in Egypt and also probably in the East as early as 1500 BCE. The name mercury originated in 6th-century alchemy, in which the symbol of the planet was used to represent the metal; the chemical symbol Hg derives from the Latin hydrargyrum, “liquid silver.” Although its toxicity was recognized at an early date, its main application was for medical purposes.

Mercury is the only elemental metal that is liquid at room temperature. (Cesium melts at about 28.5 °C [83 °F], gallium at about 30 °C [86 °F], and rubidium at about 39 °C [102 °F].) Mercury is silvery white, slowly tarnishes in moist air, and freezes into a soft solid like tin or lead at −38.87 °C (−37.97 °F). It boils at 356.9 °C (674 °F).

It alloys with copper, tin, and zinc to form amalgams, or liquid alloys. An amalgam with silver is used as a filling in dentistry. Mercury does not wet glass or cling to it, and this property, coupled with its rapid and uniform volume expansion throughout its liquid range, makes it useful in thermometers. Barometers and manometers utilize its high density and low vapour pressure. Gold and silver dissolve readily in mercury, and in the past this property was used in the extraction of these metals from their ores.

The good electrical conductivity of mercury makes it exceptionally useful in sealed electrical switches and relays. An electrical discharge through mercury vapour contained in a fused silica tube or bulb produces a bluish glow rich in ultraviolet light, a phenomenon exploited in ultraviolet, fluorescent, and high-pressure mercury-vapour lamps. Mercury’s high thermal neutron-capture cross section (360 barns) and good thermal conductivity make it applicable as a shield and coolant in nuclear reactors. Much mercury is utilized in the preparation of pharmaceuticals and agricultural and industrial fungicides.

The use of mercury in the manufacture of chlorine and caustic soda (sodium hydroxide) by electrolysis of brine depends upon the fact that mercury employed as the negative pole, or cathode, dissolves the sodium liberated to form a liquid amalgam. An interesting application, though not of great commercial significance, is the use of mercury vapour instead of steam in some electrical generating plants, the higher boiling point of mercury providing greater efficiency in the heat cycle.

Mercury occurs in Earth’s crust on the average of about 0.08 gram (0.003 ounce) per ton of rock. The principal ore is the red sulfide, cinnabar. Native mercury occurs in isolated drops and occasionally in larger fluid masses, usually with cinnabar, near volcanoes or hot springs. Over two-thirds of the world supply of mercury comes from China, with most of the remainder coming from Kyrgyzstan and Chile; it is often a by-product of gold mining. Cinnabar is mined in shaft or open-pit operations and refined by flotation. Most of the methods of extraction of mercury rely on the volatility of the metal and the fact that cinnabar is readily decomposed by air or by lime to yield the free metal. Because of the toxicity of mercury and the threat of rigid pollution control, attention is being directed toward safer methods of extracting mercury. These generally rely on the fact that cinnabar is readily soluble in solutions of sodium hypochlorite or sulfide, from which the mercury can be recovered by precipitation with zinc or aluminum or by electrolysis.

Extremely rare natural alloys of mercury have also been found: moschellandsbergite (with silver), potarite (with palladium), and gold amalgam. Mercury is extracted from cinnabar by roasting it in air, followed by condensation of the mercury vapour. Mercury is toxic. Poisoning may result from inhalation of the vapour, ingestion of soluble compounds, or absorption of mercury through the skin.

Natural mercury is a mixture of seven stable isotopes: 196Hg (0.15 percent), 198Hg (9.97 percent), 199Hg (16.87 percent), 200Hg (23.10 percent), 201Hg (13.18 percent), 202Hg (29.86 percent), and 204Hg (6.87 percent). As a wavelength standard and for other precise work, isotopically pure mercury consisting of only mercury-198 is prepared by neutron bombardment of natural gold, gold-197.

Principal Compounds

The compounds of mercury are either of +1 or +2 oxidation state. Mercury(II) or mercuric compounds predominate. Mercury does not combine with oxygen to produce mercury(II) oxide, HgO, at a useful rate until heated to the range of 300 to 350 °C (572 to 662 °F). At temperatures of about 400 °C (752 °F) and above, the reaction reverses with the compound decomposing into its elements. Antoine-Laurent Lavoisier and Joseph Priestley used this reaction in their study of oxygen.

There are relatively few mercury(I) or mercurous compounds. The mercury(I) ion, Hg22+, is diatomic and stable. Mercury(I) chloride, Hg2Cl2 (commonly known as calomel), is probably the most important univalent compound. It is used in antiseptic salves. Mercury(II) chloride, HgCl2 (also called bichloride of mercury or corrosive sublimate), is perhaps the commonest bivalent compound. Although extremely toxic, this odourless, colourless substance has a wide variety of applications. In agriculture it is used as a fungicide; in medicine it is sometimes employed as a topical antiseptic in concentrations of one part per 2,000 parts of water; and in the chemical industry it serves as a catalyst in the manufacture of vinyl chloride and as a starting material in the production of other mercury compounds. Mercury(II) oxide, HgO, provides elemental mercury for the preparation of various organic mercury compounds and certain inorganic mercury salts. This red or yellow crystalline solid is also used as an electrode (mixed with graphite) in zinc-mercuric oxide electric cells and in mercury batteries. Mercury(II) sulfide, HgS, is a black or red crystalline solid used chiefly as a pigment in paints, rubber, and plastics.

It appears to me that if one wants to make progress in mathematics, one should study the masters and not the pupils. - Niels Henrik Abel.

Nothing is better than reading and gaining more and more knowledge - Stephen William Hawking.

Online

#142 2018-05-26 17:06:14

- Jai Ganesh

- Administrator

- Registered: 2005-06-28

- Posts: 52,612

Re: Miscellany

126) Naphthalene

Naphthalene, the simplest of the fused or condensed ring hydrocarbon compounds composed of two benzene rings sharing two adjacent carbon atoms; chemical formula, C10H8. It is an important hydrocarbon raw material that gives rise to a host of substitution products used in the manufacture of dyestuffs and synthetic resins. Naphthalene is the most abundant single constituent of coal tar, a volatile product from the destructive distillation of coal, and is also formed in modern processes for the high-temperature cracking (breaking up of large molecules) of petroleum. It is commercially produced by crystallization from the intermediate fraction of condensed coal tar and from the heavier fraction of cracked petroleum. The substance crystallizes in lustrous white plates, melting at 80.1° C (176.2° F) and boiling at 218° C (424° F). It is almost insoluble in water. Naphthalene is highly volatile and has a characteristic odour; it has been used as moth repellent.

In its chemical behaviour, naphthalene shows the aromatic character associated with benzene and its simple derivatives. Its reactions are mainly reactions of substitution of hydrogen atoms by halogen atoms, nitro groups, sulfonic acid groups, and alkyl groups. Large quantities of naphthalene are converted to naphthylamines and naphthols for use as dyestuff intermediates. For many years napthalene was the principal raw material for making phthalic anhydride.

It appears to me that if one wants to make progress in mathematics, one should study the masters and not the pupils. - Niels Henrik Abel.

Nothing is better than reading and gaining more and more knowledge - Stephen William Hawking.

Online

#143 2018-05-27 22:50:01

- Jai Ganesh

- Administrator

- Registered: 2005-06-28

- Posts: 52,612

Re: Miscellany

127) Cyclotron

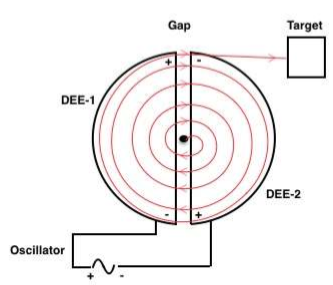

Cyclotron, any of a class of devices that accelerates charged atomic or subatomic particles in a constant magnetic field. The first particle accelerator of this type was developed in the early 1930s by the American physicists Ernest Orlando Lawrence and M. Stanley Livingston. A cyclotron consists of two hollow semicircular electrodes, called dees, mounted back to back, separated by a narrow gap, in an evacuated chamber between the poles of a magnet. An electric field, alternating in polarity, is created in the gap by a radio-frequency oscillator.

The particles to be accelerated are formed near the centre of the device in the gap, where the electric field propels them into one of the dees. There the magnetic field guides them in a semicircular path. By the time they return to the gap, the electric field has reversed, so they are accelerated into the other dee. Although the speed of the particles and the radius of their orbit increase each time they cross the gap, as long as the mass of the particles and the strength of the magnetic field remain constant, these crossings occur at a fixed frequency, to which the oscillator can be adjusted.

A cyclotron operating in this manner can accelerate protons to energies no greater than 25 million electron volts. This limitation is imposed by the relativistic increase in the mass of any particle as its speed approaches that of light. As the mass increases, the orbital frequency decreases, and the particles cross the gap at times when the electric field decelerates them.

To overcome this limitation, the frequency of the alternating voltage impressed on the dees can be varied to match that of the orbiting particles. A device with this feature is called a synchrocyclotron, and energies close to one billion electron volts have been achieved with it. Another technique is to strengthen the magnetic field near the periphery of the dees and to effect focusing by azimuthal variation of the magnetic field. Accelerators operated in this way are called isochronous, or azimuthally-varying-field (AVF) cyclotrons.

It appears to me that if one wants to make progress in mathematics, one should study the masters and not the pupils. - Niels Henrik Abel.

Nothing is better than reading and gaining more and more knowledge - Stephen William Hawking.

Online

#144 2018-05-28 22:28:35

- Jai Ganesh

- Administrator

- Registered: 2005-06-28

- Posts: 52,612

Re: Miscellany

128) Lightning Rod

Lightning rod, metallic rod (usually copper) that protects a structure from lightning damage by intercepting flashes and guiding their currents into the ground. Because lightning tends to strike the highest object in the vicinity, rods are typically placed at the apex of a structure and along its ridges; they are connected to the ground by low-impedance cables. In the case of a building, the soil is used as the ground; on a ship, the water is used.

A lightning rod and its associated grounding conductors provide protection because they divert the current from nonconducting parts of the structure, allowing it to follow the path of least resistance and pass harmlessly through the rod and its cables. It is the high resistance of the nonconducting materials that causes them to be heated by the passage of electric current, leading to fire and other damage. On structures less than 30 metres (about 100 feet) in height, a lightning rod provides a cone of protection whose ground radius approximately equals its height above the ground. On taller structures, the area of protection extends only about 30 metres from the base of the structure.

It appears to me that if one wants to make progress in mathematics, one should study the masters and not the pupils. - Niels Henrik Abel.

Nothing is better than reading and gaining more and more knowledge - Stephen William Hawking.

Online

#145 2018-05-30 01:21:57

- Jai Ganesh

- Administrator

- Registered: 2005-06-28

- Posts: 52,612

Re: Miscellany

129) Carbon tetrachloride

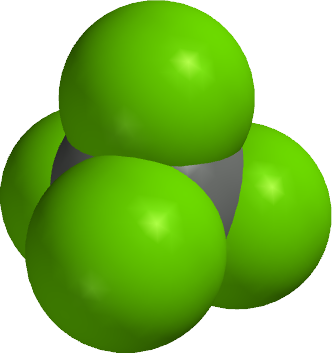

Carbon tetrachloride, also called tetrachloromethane, a colourless, dense, highly toxic, volatile, nonflammable liquid possessing a characteristic odour and belonging to the family of organic halogen compounds, used principally in the manufacture of dichlorodifluoromethane (a refrigerant and propellant).

First prepared in 1839 by the reaction of chloroform with chlorine, carbon tetrachloride is manufactured by the reaction of chlorine with carbon disulfide or with methane. The process with methane became dominant in the United States in the 1950s, but the process with carbon disulfide remains important in countries where natural gas (the principal source of methane) is not plentiful. Carbon tetrachloride boils at 77° C (171° F) and freezes at -23° C (-9° F); it is much denser than water, in which it is practically insoluble.

Formerly used as a dry-cleaning solvent, carbon tetrachloride has been almost entirely displaced from this application by tetrachloroethylene, which is much more stable and less toxic.

It appears to me that if one wants to make progress in mathematics, one should study the masters and not the pupils. - Niels Henrik Abel.

Nothing is better than reading and gaining more and more knowledge - Stephen William Hawking.

Online

#146 2018-06-01 01:18:44

- Jai Ganesh

- Administrator

- Registered: 2005-06-28

- Posts: 52,612

Re: Miscellany

130) Voltmeter

Voltmeter, instrument that measures voltages of either direct or alternating electric current on a scale usually graduated in volts, millivolts (0.001 volt), or kilovolts (1,000 volts). The typical commercial or laboratory standard voltmeter in use today is likely to employ an electromechanical mechanism in which current flowing through turns of wire is translated into a reading of voltage. Other types of voltmeters include the electrostatic voltmeter, which uses electrostatic forces and, thus, is the only voltmeter to measure voltage directly rather than by the effect of current. The potentiometer operates by comparing the voltage to be measured with known voltage; it is used to measure very low voltages. The electronic voltmeter, which has largely replaced the vacuum-tube voltmeter, uses amplification or rectification (or both) to measure either alternating- or direct-current voltages. The current needed to actuate the meter movement is not taken from the circuit being measured; hence, this type of instrument does not introduce errors of circuit loading.

The instruments just described provide readings in analogue form, by moving a pointer that indicates voltage on a scale. Digital voltmeters give readings as numerical displays. They also provide outputs that can be transmitted over distance, can activate printers or typewriters, and can feed into computers. Digital voltmeters generally have a higher order of accuracy than analogue instruments.

An instrument that also measures ohms and amperes (in milliamperes) is known as a volt-ohm-milliammeter, or sometimes as a multimeter.

It appears to me that if one wants to make progress in mathematics, one should study the masters and not the pupils. - Niels Henrik Abel.

Nothing is better than reading and gaining more and more knowledge - Stephen William Hawking.

Online

#147 2018-06-03 00:23:46

- Jai Ganesh

- Administrator

- Registered: 2005-06-28

- Posts: 52,612

Re: Miscellany

131) Freon

Freon, (trademark), any of several simple fluorinated aliphatic organic compounds that are used in commerce and industry. In addition to fluorine and carbon, Freons often contain hydrogen, chlorine, or bromine. Thus, Freons are types of chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs), hydrochlorofluorocarbons (HCFCs), and related compounds. The name Freon is a trademark registered by E.I. du Pont de Nemours & Company.

The Freons are colourless, odourless, nonflammable, noncorrosive gases or liquids of low toxicity that were introduced as refrigerants in the 1930s; they also proved useful as propellants for aerosols and in numerous technical applications. Their low boiling points, low surface tension, and low viscosity make them especially useful refrigerants. They are extremely stable, inert compounds. The Freons neither present a fire hazard nor give off a detectable odour in their circulation through refrigerating and air-conditioning systems. The most important members of the group have been dichlorodifluoromethane (Freon 12), trichlorofluoromethane (Freon 11), chlorodifluoromethane (Freon 22), dichlorotetrafluoroethane (Freon 114), and trichlorotrifluoroethane (Freon 113).

In the mid-1970s, photochemical dissociation of Freons and related CFCs was implicated as a major cause of the apparent degradation of Earth’s ozone layer. Depletion of the ozone could create a threat to animal life on Earth because ozone absorbs ultraviolet radiation that can induce skin cancer. The use of Freons in aerosol-spray containers was banned in the United States in the late 1970s. By the early 1990s, accumulating evidence of ozone depletion in the polar regions had heightened worldwide public alarm over the problem, and by 1996 most developed countries had banned the production of nearly all Freons.

It appears to me that if one wants to make progress in mathematics, one should study the masters and not the pupils. - Niels Henrik Abel.

Nothing is better than reading and gaining more and more knowledge - Stephen William Hawking.

Online

#148 2018-06-04 23:46:02

- Jai Ganesh

- Administrator

- Registered: 2005-06-28

- Posts: 52,612

Re: Miscellany

132) Down Syndrome

Down syndrome is a genetic disorder caused when abnormal cell division results in an extra full or partial copy of chromosome 21. This extra genetic material causes the developmental changes and physical features of Down syndrome.

Down syndrome varies in severity among individuals, causing lifelong intellectual disability and developmental delays. It's the most common genetic chromosomal disorder and cause of learning disabilities in children. It also commonly causes other medical abnormalities, including heart and gastrointestinal disorders.

Better understanding of Down syndrome and early interventions can greatly increase the quality of life for children and adults with this disorder and help them live fulfilling lives.

Symptoms

Each person with Down syndrome is an individual — intellectual and developmental problems may be mild, moderate or severe. Some people are healthy while others have significant health problems such as serious heart defects.

Children and adults with Down syndrome have distinct facial features. Though not all people with Down syndrome have the same features, some of the more common features include:

Flattened face

Small head

Short neck

Protruding tongue

Upward slanting eye lids (palpebral fissures)

Unusually shaped or small ears

Poor muscle tone

Broad, short hands with a single crease in the palm

Relatively short fingers and small hands and feet

Excessive flexibility

Tiny white spots on the colored part (iris) of the eye called Brushfield's spots

Short height

Infants with Down syndrome may be average size, but typically they grow slowly and remain shorter than other children the same age.

Intellectual disabilities

Most children with Down syndrome have mild to moderate cognitive impairment. Language is delayed, and both short and long-term memory is affected.

When to see a doctor

Children with Down syndrome usually are diagnosed before or at birth. However, if you have any questions regarding your pregnancy or your child's growth and development, talk with your doctor.

Causes

Human cells normally contain 23 pairs of chromosomes. One chromosome in each pair comes from your father, the other from your mother.

Down syndrome results when abnormal cell division involving chromosome 21 occurs. These cell division abnormalities result in an extra partial or full chromosome 21. This extra genetic material is responsible for the characteristic features and developmental problems of Down syndrome. Any one of three genetic variations can cause Down syndrome:

Trisomy 21. About 95 percent of the time, Down syndrome is caused by trisomy 21 — the person has three copies of chromosome 21, instead of the usual two copies, in all cells. This is caused by abnormal cell division during the development of the sperm cell or the egg cell.

Mosaic Down syndrome. In this rare form of Down syndrome, a person has only some cells with an extra copy of chromosome 21. This mosaic of normal and abnormal cells is caused by abnormal cell division after fertilization.

Translocation Down syndrome. Down syndrome can also occur when a portion of chromosome 21 becomes attached (translocated) onto another chromosome, before or at conception. These children have the usual two copies of chromosome 21, but they also have additional genetic material from chromosome 21 attached to another chromosome.

There are no known behavioral or environmental factors that cause Down syndrome.

Is it inherited?

Most of the time, Down syndrome isn't inherited. It's caused by a mistake in cell division during early development of the fetus.

Translocation Down syndrome can be passed from parent to child. However, only about 3 to 4 percent of children with Down syndrome have translocation and only some of them inherited it from one of their parents.

When balanced translocations are inherited, the mother or father has some rearranged genetic material from chromosome 21 on another chromosome, but no extra genetic material. This means he or she has no signs or symptoms of Down syndrome, but can pass an unbalanced translocation on to children, causing Down syndrome in the children.

Risk factors

Some parents have a greater risk of having a baby with Down syndrome. Risk factors include:

Advancing maternal age. A woman's chances of giving birth to a child with Down syndrome increase with age because older eggs have a greater risk of improper chromosome division. A woman's risk of conceiving a child with Down syndrome increases after 35 years of age. However, most children with Down syndrome are born to women under age 35 because younger women have far more babies.

Being carriers of the genetic translocation for Down syndrome. Both men and women can pass the genetic translocation for Down syndrome on to their children.

Having had one child with Down syndrome. Parents who have one child with Down syndrome and parents who have a translocation themselves are at an increased risk of having another child with Down syndrome. A genetic counselor can help parents assess the risk of having a second child with Down syndrome.

Complications

People with Down syndrome can have a variety of complications, some of which become more prominent as they get older. These complications can include:

Heart defects. About half the children with Down syndrome are born with some type of congenital heart defect. These heart problems can be life-threatening and may require surgery in early infancy.

Gastrointestinal (GI) defects. GI abnormalities occur in some children with Down syndrome and may include abnormalities of the intestines, esophagus, trachea and math. The risk of developing digestive problems, such as GI blockage, heartburn (gastroesophageal reflux) or celiac disease, may be increased.

Immune disorders. Because of abnormalities in their immune systems, people with Down syndrome are at increased risk of developing autoimmune disorders, some forms of cancer, and infectious diseases, such as pneumonia.

Sleep apnea. Because of soft tissue and skeletal changes that lead to the obstruction of their airways, children and adults with Down syndrome are at greater risk of obstructive sleep apnea.

Obesity. People with Down syndrome have a greater tendency to be obese compared with the general population.

Spinal problems. Some people with Down syndrome may have a misalignment of the top two vertebrae in the neck (atlantoaxial instability). This condition puts them at risk of serious injury to the spinal cord from overextension of the neck.

Leukemia. Young children with Down syndrome have an increased risk of leukemia.

Dementia. People with Down syndrome have a greatly increased risk of dementia — signs and symptoms may begin around age 50. Having Down syndrome also increases the risk of developing Alzheimer's disease.

Other problems. Down syndrome may also be associated with other health conditions, including endocrine problems, dental problems, seizures, ear infections, and hearing and vision problems.

For people with Down syndrome, getting routine medical care and treating issues when needed can help with maintaining a healthy lifestyle.

Life expectancy

Life spans have increased dramatically for people with Down syndrome. Today, someone with Down syndrome can expect to live more than 60 years, depending on the severity of health problems.

Prevention

There's no way to prevent Down syndrome. If you're at high risk of having a child with Down syndrome or you already have one child with Down syndrome, you may want to consult a genetic counselor before becoming pregnant.

A genetic counselor can help you understand your chances of having a child with Down syndrome. He or she can also explain the prenatal tests that are available and help explain the pros and cons of testing.

It appears to me that if one wants to make progress in mathematics, one should study the masters and not the pupils. - Niels Henrik Abel.

Nothing is better than reading and gaining more and more knowledge - Stephen William Hawking.

Online

#149 2018-06-07 01:00:56

- Jai Ganesh

- Administrator

- Registered: 2005-06-28

- Posts: 52,612

Re: Miscellany

133) Gigantism

Gigantism, excessive growth in stature, well beyond the average for the individual’s heredity and environmental conditions. Tall stature may result from hereditary, dietary, or other factors. Gigantism is caused by disease or disorder in those parts of the endocrine system that regulate growth and development. Androgen deficiency, for example, delays the closure of end plates, or epiphyses, of the long bones, which usually takes place when full growth is achieved. If the pituitary gland functions normally, producing appropriate amounts of growth hormone, while epiphyseal closure is delayed, the growth period of the bones will be prolonged. Gigantism associated with androgen deficiency is more frequent in men than in women and may be genetic.

Another type of gigantism associated with endocrine disorder is pituitary gigantism, caused by hypersecretion of growth hormone (somatotropin), during childhood or adolescence, prior to epiphyseal closure. Pituitary gigantism is usually associated with a tumour of the pituitary gland. Acromegaly (q.v.), a condition marked by progressive enlargement of skeletal extremities, occurs if growth hormone continues to be produced in large volume after epiphyseal closure. (Signs of acromegaly are occasionally seen in younger patients, prior to closure.) Since most pituitary giants continue to produce growth hormone after they reach adulthood, the two conditions—gigantism and acromegaly—are often concurrent.

In pituitary gigantism, growth is gradual but continuous and consistent; the affected person, with bones in normal proportion, may attain a height of eight feet. Muscles may be well developed but later undergo some atrophy or weakening. The life span of pituitary giants is shorter than normal because of their greater susceptibility to infection and metabolic disorders. Treatment by surgery or irradiation of the pituitary gland curtails further growth, but stature cannot be reduced once gigantism has occurred.

It appears to me that if one wants to make progress in mathematics, one should study the masters and not the pupils. - Niels Henrik Abel.

Nothing is better than reading and gaining more and more knowledge - Stephen William Hawking.

Online

#150 2018-06-09 00:13:15

- Jai Ganesh

- Administrator

- Registered: 2005-06-28

- Posts: 52,612

Re: Miscellany

134) Game theory

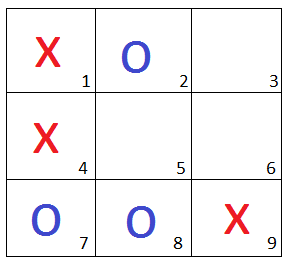

Game theory, branch of applied mathematics that provides tools for analyzing situations in which parties, called players, make decisions that are interdependent. This interdependence causes each player to consider the other player’s possible decisions, or strategies, in formulating his own strategy. A solution to a game describes the optimal decisions of the players, who may have similar, opposed, or mixed interests, and the outcomes that may result from these decisions.

Although game theory can be and has been used to analyze parlour games, its applications are much broader. In fact, game theory was originally developed by the Hungarian-born American mathematician John von Neumann and his Princeton University colleague Oskar Morgenstern, a German-born American economist, to solve problems in economics. In their book The Theory of Games and Economic Behavior (1944), von Neumann and Morgenstern asserted that the mathematics developed for the physical sciences, which describes the workings of a disinterested nature, was a poor model for economics. They observed that economics is much like a game, wherein players anticipate each other’s moves, and therefore requires a new kind of mathematics, which they called game theory. (The name may be somewhat of a misnomer - game theory generally does not share the fun or frivolity associated with games.)

Game theory has been applied to a wide variety of situations in which the choices of players interact to affect the outcome. In stressing the strategic aspects of decision making, or aspects controlled by the players rather than by pure chance, the theory both supplements and goes beyond the classical theory of probability. It has been used, for example, to determine what political coalitions or business conglomerates are likely to form, the optimal price at which to sell products or services in the face of competition, the power of a voter or a bloc of voters, whom to select for a jury, the best site for a manufacturing plant, and the behaviour of certain animals and plants in their struggle for survival. It has even been used to challenge the legality of certain voting systems.

It would be surprising if any one theory could address such an enormous range of “games,” and in fact there is no single game theory. A number of theories have been proposed, each applicable to different situations and each with its own concepts of what constitutes a solution. This article describes some simple games, discusses different theories, and outlines principles underlying game theory. Additional concepts and methods that can be used to analyze and solve decision problems are treated in the article optimization.

It appears to me that if one wants to make progress in mathematics, one should study the masters and not the pupils. - Niels Henrik Abel.

Nothing is better than reading and gaining more and more knowledge - Stephen William Hawking.

Online