Math Is Fun Forum

You are not logged in.

- Topics: Active | Unanswered

#2451 2025-02-04 00:08:29

- Jai Ganesh

- Administrator

- Registered: 2005-06-28

- Posts: 52,770

Re: Miscellany

2350) Dental Implant

Gist

An implant is a medical device manufactured to replace a missing biological structure, support a damaged biological structure, or enhance an existing biological structure. For example, an implant may be a rod, used to strengthen weak bones.

A dental implant is a metal post that replaces the root portion of a missing tooth. A dental professional places an artificial tooth, also known as a crown, on an extension of the post of the dental implant, giving you the look of a real tooth.

Summary:

Overview

Dental implant, abutment and new tooth in jawbone to replace missing tooth

A dental implant replaces a missing tooth root. Once the implant heals, your dentist can restore it with an artificial tooth.

What are dental implants?

Dental implants are small, threaded posts that surgically replace missing teeth. In addition to filling in gaps in your smile, dental implants improve chewing function and overall oral health. Once healed, implants work much like natural teeth.

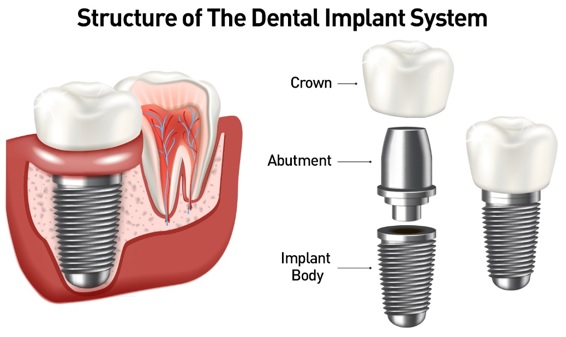

A dental implant has three main parts:

* Threaded post: You can think of this like an artificial tooth root. A provider places it in your jawbone during an oral surgery procedure.

* Abutment: This is a tiny connector post. It screws into the threaded post and extends slightly beyond your gums. It serves as the foundation for your new artificial tooth.

* Restoration: A dental restoration is any prosthetic that repairs or replaces teeth. Common dental implant restorations are crowns, bridges and dentures.

Most dental implants are titanium, but some are ceramic. Both materials are safe and biocompatible (friendly to the tissues inside of your mouth).

Missing teeth can take a toll on your oral health. But it also impacts your mental and emotional well-being. Do you avoid social situations? Or cover your mouth when you laugh? Do you rarely smile for photos? Dental implants can restore your smile and your confidence, so you don’t have to miss out on the things you enjoy.

What conditions are treated with dental implants?

Dental implants treat tooth loss, which can happen due to:

* Cavities.

* Cracked teeth.

* Gum disease.

* Teeth that never develop (anodontia).

* Teeth grinding or clenching (bruxism).

How common are dental implants?

Dental implants are a popular choice for tooth replacement. In the United States, dental providers place over 3 million implants each year.

Details

A dental implant (also known as an endosseous implant or fixture) is a prosthesis that interfaces with the bone of the jaw or skull to support a dental prosthesis such as a crown, bridge, denture, or facial prosthesis or to act as an orthodontic anchor. The basis for modern dental implants is a biological process called osseointegration, in which materials such as titanium or zirconia form an intimate bond to the bone. The implant fixture is first placed so that it is likely to osseointegrate, then a dental prosthetic is added. A variable amount of healing time is required for osseointegration before either the dental prosthetic (a tooth, bridge, or denture) is attached to the implant or an abutment is placed which will hold a dental prosthetic or crown.

Success or failure of implants depends primarily on the thickness and health of the bone and gingival tissues that surround the implant, but also on the health of the person receiving the treatment and drugs which affect the chances of osseointegration. The amount of stress that will be put on the implant and fixture during normal function is also evaluated. Planning the position and number of implants is key to the long-term health of the prosthetic since biomechanical forces created during chewing can be significant. The position of implants is determined by the position and angle of adjacent teeth, by lab simulations or by using computed tomography with CAD/CAM simulations and surgical guides called stents. The prerequisites for long-term success of osseointegrated dental implants are healthy bone and gingiva. Since both can atrophy after tooth extraction, pre-prosthetic procedures such as sinus lifts or gingival grafts are sometimes required to recreate ideal bone and gingiva.

The final prosthetic can be either fixed, where a person cannot remove the denture or teeth from their mouth, or removable, where they can remove the prosthetic. In each case an abutment is attached to the implant fixture. Where the prosthetic is fixed, the crown, bridge or denture is fixed to the abutment either with lag screws or with dental cement. Where the prosthetic is removable, a corresponding adapter is placed in the prosthetic so that the two pieces can be secured together.

The risks and complications related to implant therapy divide into those that occur during surgery (such as excessive bleeding or nerve injury, inadequate primary stability), those that occur in the first six months (such as infection and failure to osseointegrate) and those that occur long-term (such as peri-implantitis and mechanical failures). In the presence of healthy tissues, a well-integrated implant with appropriate biomechanical loads can have 5-year plus survival rates from 93 to 98 percent and 10-to-15-year lifespans for the prosthetic teeth. Long-term studies show a 16- to 20-year success (implants surviving without complications or revisions) between 52% and 76%, with complications occurring up to 48% of the time. Artificial intelligence is relevant as the basis for clinical decision support systems at the present time. Intelligent systems are used as an aid in determining the success rate of implants.

Medical uses

The primary use of dental implants is to support dental prosthetics (i.e. false teeth). Modern dental implants work through a biologic process where bone fuses tightly to the surface of specific materials such as titanium and some ceramics. The integration of implant and bone can support physical loads for decades without failure.

The US has seen an increasing use of dental implants, with usage increasing from 0.7% of patients missing at least one tooth (1999–2000), to 5.7% (2015–2016), and was projected to potentially reach 26% in 2026. Implants are used to replace missing individual teeth (single tooth restorations), multiple teeth, or to restore edentulous (toothless) dental arches (implant retained fixed bridge, implant-supported overdenture). While use of dental implants in the US has increased, other treatments to tooth loss exist.

Dental implants are also used in orthodontics to provide anchorage (orthodontic mini implants). Orthodontic treatment might be required prior to placing a dental implant.

An evolving field is the use of implants to retain obturators (removable prostheses used to fill a communication between the oral and maxillary or nasal cavities). Facial prosthetics, used to correct facial deformities (e.g. from cancer treatment or injuries), can use connections to implants placed in the facial bones. Depending on the situation the implant may be used to retain either a fixed or removable prosthetic that replaces part of the face.

Single tooth implant restoration

Single tooth restorations are individual freestanding units not connected to other teeth or implants, used to replace missing individual teeth. For individual tooth replacement, an implant abutment is first secured to the implant with an abutment screw. A crown (the dental prosthesis) is then connected to the abutment with dental cement, a small screw, or fused with the abutment as one piece during fabrication. Dental implants, in the same way, can also be used to retain a multiple tooth dental prosthesis either in the form of a fixed bridge or removable dentures.

There is limited evidence that implant-supported single crowns perform better than tooth-supported fixed partial dentures (FPDs) on a long-term basis. However, taking into account the favorable cost-benefit ratio and the high implant survival rate, dental implant therapy is the first-line strategy for single-tooth replacement. Implants preserve the integrity of the teeth adjacent to the edentulous area, and it has been shown that dental implant therapy is less costly and more efficient over time than tooth-supported FPDs for the replacement of one missing tooth. The major disadvantage of dental implant surgery is the need for a surgical procedure.

Implant retained fixed bridge or implant supported bridge

An implant supported bridge (or fixed denture) is a group of teeth secured to dental implants so the prosthetic cannot be removed by the user. They are similar to conventional bridges, except that the prosthesis is supported and retained by one or more implants instead of natural teeth. Bridges typically connect to more than one implant and may also connect to teeth as anchor points. Typically the number of teeth will outnumber the anchor points with the teeth that are directly over the implants referred to as abutments and those between abutments referred to as pontics. Implant supported bridges attach to implant abutments in the same way as a single tooth implant replacement. A fixed bridge may replace as few as two teeth (also known as a fixed partial denture) and may extend to replace an entire arch of teeth (also known as a fixed full denture). In both cases, the prosthesis is said to be fixed because it cannot be removed by the denture wearer.

Implant-supported overdenture

A removable implant-supported denture (also an implant-supported overdenture) is a removable prosthesis which replaces teeth, using implants to improve support, retention and stability. They are most commonly complete dentures (as opposed to partial), used to restore edentulous dental arches. The dental prosthesis can be disconnected from the implant abutments with finger pressure by the wearer. To enable this, the abutment is shaped as a small connector (a button, ball, bar or magnet) which can be connected to analogous adapters in the underside of the dental prosthesis.

Orthodontic mini-implants (TAD)

Dental implants are used in orthodontic patients to replace missing teeth (as above) or as a temporary anchorage device (TAD) to facilitate orthodontic movement by providing an additional anchorage point. For teeth to move, a force must be applied to them in the direction of the desired movement. The force stimulates cells in the periodontal ligament to cause bone remodeling, removing bone in the direction of travel of the tooth and adding it to the space created. In order to generate a force on a tooth, an anchor point (something that will not move) is needed. Since implants do not have a periodontal ligament, and bone remodelling will not be stimulated when tension is applied, they are ideal anchor points in orthodontics. Typically, implants designed for orthodontic movement are small and do not fully osseointegrate, allowing easy removal following treatment.[20] They are indicated when needing to shorten treatment time, or as an alternative to extra-oral anchorage. Mini-implants are frequently placed between the roots of teeth, but may also be sited in the roof of the mouth. They are then connected to a fixed brace to help move the teeth.

Small-diameter implants (mini-implants)

The introduction of small-diameter implants has provided dentists the means of providing edentulous and partially edentulous patients with immediate functioning transitional prostheses while definitive restorations are being fabricated. Many clinical studies have been done on the success of long-term usage of these implants. Based on the findings of many studies, mini dental implants exhibit excellent survival rates in the short to medium term (3–5 years). They appear to be a reasonable alternative treatment modality to retain mandibular complete overdentures from the available evidence.

Composition

A typical conventional implant consists of a titanium screw (resembling a tooth root) with a roughened or smooth surface. The majority of dental implants are made of commercially pure titanium, which is available in four grades depending upon the amount of carbon, nitrogen, oxygen and iron contained. Cold work hardened CP4 (maximum impurity limits of N .05 percent, C .10 percent, H .015 percent, Fe .50 percent, and O .40 percent) is the most commonly used titanium for implants. Grade 5 titanium, Titanium 6AL-4V (signifying the titanium alloy containing 6 percent aluminium and 4 percent vanadium alloy) is slightly harder than CP4 and used in the industry mostly for abutment screws and abutments. Most modern dental implants also have a textured surface (through etching, anodic oxidation or various-media blasting) to increase the surface area and osseointegration potential of the implant. If C.P. titanium or a titanium alloy has more than 85% titanium content, it will form a titanium-biocompatible titanium oxide surface layer or veneer that encloses the other metals, preventing them from contacting the bone.

Ceramic (zirconia-based) implants exist in one-piece (combining the screw and the abutment) or two-piece systems - the abutment being either cemented or screwed – and might lower the risk for peri‐implant diseases, but long-term data on success rates is missing.

Additional Information

Dental implant surgery replaces tooth roots with metal, screwlike posts and replaces damaged or missing teeth with artificial teeth that look and work much like real ones. Dental implant surgery can be a helpful choice when dentures or bridgework fit poorly. This surgery also can be an option when there aren't enough natural teeth roots to support dentures or build bridgework tooth replacements.

The type of implant and the condition of the jawbone guide how dental implant surgery is done. This surgery may involve several procedures. The major benefit of implants is solid support for the new teeth — a process that requires the bone to heal tightly around the implant. Because this bone healing requires time, the process can take many months.

Why it's done

Dental implants are surgically placed in your jawbone and serve as the roots of missing teeth. Because the titanium in the implants fuses with your jawbone, the implants won't slip, make noise or cause bone damage like fixed bridgework or dentures might. And the materials can't decay like your own teeth.

Dental implants may be right for you if you:

* Have one or more missing teeth.

* Have a jawbone that's reached full growth.

* Have enough bone to secure the implants or can have a bone graft.

* Have healthy tissues in your mouth.

* Don't have health conditions that can affect bone healing.

* Aren't able or willing to wear dentures.

* Want to improve your speech.

* Are willing to commit several months to the process.

* Don't smoke tobacco.

It appears to me that if one wants to make progress in mathematics, one should study the masters and not the pupils. - Niels Henrik Abel.

Nothing is better than reading and gaining more and more knowledge - Stephen William Hawking.

Offline

#2452 2025-02-06 21:54:36

- Jai Ganesh

- Administrator

- Registered: 2005-06-28

- Posts: 52,770

Re: Miscellany

2351) Astrophysics/Astrophysicist

Gist

Astrophysics is a branch of space science that applies the laws of physics and chemistry to seek to understand the universe and our place in it. The field explores topics such as the birth, life and death of stars, planets, galaxies, nebulae and other objects in the universe.

Astronomers or astrophysicists study the universe to help us understand the physical matter and processes in our own solar system and other galaxies. It involves studying large objects, such as planets, as well as tiny particles.

Summary

An astrophysicist is a scientist, who studies the physical properties, processes and physics of things beyond the Earth. This includes the moon, the sun, the planets in our solar system and the galaxies which aren’t obvious to the human eye.

Working as an astrophysicist, you’ll use the expert knowledge of physics, astronomy and mathematics and apply it to explore the wonders of space such as black holes, superclusters and dark matter for example. The main purpose of the role is to figure out the origins of the universe, how it all works, what our place is within it, search for life on other planets around other stars and some, even look to predict the universe's ending.

It’s a highly skilled role where astrophysicists are educated across many disciplines.

Two types of astrophysicists complement each other's roles and they include the theoretical astrophysicist and the observational astrophysicist. Theoretical astrophysicists seek to explain observational results and observational astrophysicists help to confirm theories.

* Theoretical astrophysicists: These are the theoretical side of astrophysics, hence the name. They develop analytical or computer models to describe astronomical objects, and then use the models to pose theories about them. As what they’re analysing is too far away from reach, they’ll use properties of maths and physics to test the theories.

* Observational astrophysicists: These are the more practical side of astrophysics. Their focus is on acquiring data from celestial object observation and then analysing it, using physical. The work is similar to an astronomer, the role of observing the objects in outer space.

Responsibilities

As an astrophysicist, the responsibilities can vary, but generally, they include:

* Collaborating with other astrophysicists and working on research projects.

* Observing and analysing celestial bodies.

* Creating theories based on observations and the laws of physics.

* Testing your theories to find answers in a better understanding of the universe.

* Writing up research and essays on discoveries.

* Attending various lectures and conferences about research discoveries.

* The ability to use ground-based equipment and telescopes to explore space.

* Analysing research data and determining its purpose and significance.

* Performing presentations of your discoveries and research.

* Reviewing research from other scientists.

* Helping raise funds for scientific research and writing grant proposals.

* Teaching and training PhD candidates.

* The ability to measure emissions included infrared, gamma and x-ray from extraterrestrial sources.

* Assisting with calculating orbits and figuring out shapes, brightness, sizes and more.

Qualifications

An astrophysicist job is a master’s graduate career. Most employers at least require master’s astrophysics degrees, whilst many also require a doctoral PhD degree.

There are many relevant degrees you can study to aid your career as an astrophysicist. Before applying for your master’s you’ll need to acquire a bachelor’s (BA) degree. Any BA degree in a scientific field is useful such as astronomy degrees, physics degrees, maths degrees or a similar subject.

The next step is applying for your master’s degree to continue your scientific studies. The master’s degree will need to be in a specific subject such as astrophysics or astronomy degrees and will take around a year to complete. The last step in qualifying is gaining your PhD in astrophysics, which can take around three to four years to complete. As part of your PhD, you will need to create a dissertation which showcases all the research and findings you’ve made when studying.

Training and development

As astrophysicists, training is usually provided when studying and on the job. Entry-level astrophysicists can expect to work closely with their supervisors and professional astrophysicists to gain industry experience and see what the day-to-day role entails.

It’s also essential for astrophysicists to take responsibility into their own hands and keep up to date with the latest industry findings, and how you can apply them to new projects. You can do this by reading relevant journals, and scientific papers, watching documentaries and staying in the know with industry news.

Skills

As an astrophysicist, skills can vary from theory-based to practical skills. These are the skills required to become an astrophysicist:

* Strong analytical skills when conducting research projects, acquiring data and writing up reports of findings.

* The ability of a good researcher, to test your theories and report back to all other professionals in your team.

* Excellent mathematics skills to help test theories and report on data.

* Good at problem-solving, relating to your research and being able to identify problems in the first place.

* Create a hypothesis and take the steps to either prove or disprove a theory.

* Confident with using computers and various programmes.

* Strong written skills and verbal communication skills.

* Great knowledge of using astrophysics equipment and tools.

* In-depth understanding of the process of raising funds for scientific research.

Career prospects

As a qualified astrophysicist, you will initially work either within a university or research institution. Through years of experience, your position may become permanent and you will move up the ranks into a more senior role, in that university, research institution or observatory.

You could also go into teaching either public or privately in schools, colleges or universities as a lecturer. There’s the option to move into journalism to share your astrophysics expertise. Alternatively, you could head down the scientific research job route in a private company, or travel around to present your research and theories worldwide.

Based on your qualifications, there’s also the option to go into other fields including private/public research and development, healthcare technology and energy production, plus many more.

Details

Astrophysics is a science that employs the methods and principles of physics and chemistry in the study of astronomical objects and phenomena. As one of the founders of the discipline, James Keeler, said, astrophysics "seeks to ascertain the nature of the heavenly bodies, rather than their positions or motions in space—what they are, rather than where they are", which is studied in celestial mechanics.

Among the subjects studied are the Sun (solar physics), other stars, galaxies, extrasolar planets, the interstellar medium, and the cosmic microwave background. Emissions from these objects are examined across all parts of the electromagnetic spectrum, and the properties examined include luminosity, density, temperature, and chemical composition. Because astrophysics is a very broad subject, astrophysicists apply concepts and methods from many disciplines of physics, including classical mechanics, electromagnetism, statistical mechanics, thermodynamics, quantum mechanics, relativity, nuclear and particle physics, and atomic and molecular physics.

In practice, modern astronomical research often involves substantial work in the realms of theoretical and observational physics. Some areas of study for astrophysicists include the properties of dark matter, dark energy, black holes, and other celestial bodies; and the origin and ultimate fate of the universe. Topics also studied by theoretical astrophysicists include Solar System formation and evolution; stellar dynamics and evolution; galaxy formation and evolution; magnetohydrodynamics; large-scale structure of matter in the universe; origin of cosmic rays; general relativity, special relativity, and quantum and physical cosmology (the physical study of the largest-scale structures of the universe), including string cosmology and astroparticle physics.

History

Astronomy is an ancient science, long separated from the study of terrestrial physics. In the Aristotelian worldview, bodies in the sky appeared to be unchanging spheres whose only motion was uniform motion in a circle, while the earthly world was the realm which underwent growth and decay and in which natural motion was in a straight line and ended when the moving object reached its goal. Consequently, it was held that the celestial region was made of a fundamentally different kind of matter from that found in the terrestrial sphere; either Fire as maintained by Plato, or Aether as maintained by Aristotle. During the 17th century, natural philosophers such as Galileo, Descartes, and Newton began to maintain that the celestial and terrestrial regions were made of similar kinds of material and were subject to the same natural laws. Their challenge was that the tools had not yet been invented with which to prove these assertions.

For much of the nineteenth century, astronomical research was focused on the routine work of measuring the positions and computing the motions of astronomical objects. A new astronomy, soon to be called astrophysics, began to emerge when William Hyde Wollaston and Joseph von Fraunhofer independently discovered that, when decomposing the light from the Sun, a multitude of dark lines (regions where there was less or no light) were observed in the spectrum. By 1860 the physicist, Gustav Kirchhoff, and the chemist, Robert Bunsen, had demonstrated that the dark lines in the solar spectrum corresponded to bright lines in the spectra of known gases, specific lines corresponding to unique chemical elements. Kirchhoff deduced that the dark lines in the solar spectrum are caused by absorption by chemical elements in the Solar atmosphere. In this way it was proved that the chemical elements found in the Sun and stars were also found on Earth.

Among those who extended the study of solar and stellar spectra was Norman Lockyer, who in 1868 detected radiant, as well as dark lines in solar spectra. Working with chemist Edward Frankland to investigate the spectra of elements at various temperatures and pressures, he could not associate a yellow line in the solar spectrum with any known elements. He thus claimed the line represented a new element, which was called helium, after the Greek Helios, the Sun personified.

In 1885, Edward C. Pickering undertook an ambitious program of stellar spectral classification at Harvard College Observatory, in which a team of woman computers, notably Williamina Fleming, Antonia Maury, and Annie Jump Cannon, classified the spectra recorded on photographic plates. By 1890, a catalog of over 10,000 stars had been prepared that grouped them into thirteen spectral types. Following Pickering's vision, by 1924 Cannon expanded the catalog to nine volumes and over a quarter of a million stars, developing the Harvard Classification Scheme which was accepted for worldwide use in 1922.

In 1895, George Ellery Hale and James E. Keeler, along with a group of ten associate editors from Europe and the United States, established The Astrophysical Journal: An International Review of Spectroscopy and Astronomical Physics. It was intended that the journal would fill the gap between journals in astronomy and physics, providing a venue for publication of articles on astronomical applications of the spectroscope; on laboratory research closely allied to astronomical physics, including wavelength determinations of metallic and gaseous spectra and experiments on radiation and absorption; on theories of the Sun, Moon, planets, comets, meteors, and nebulae; and on instrumentation for telescopes and laboratories.

Around 1920, following the discovery of the Hertzsprung–Russell diagram still used as the basis for classifying stars and their evolution, Arthur Eddington anticipated the discovery and mechanism of nuclear fusion processes in stars, in his paper The Internal Constitution of the Stars. At that time, the source of stellar energy was a complete mystery; Eddington correctly speculated that the source was fusion of hydrogen into helium, liberating enormous energy according to Einstein's equation E = m{c}^2. This was a particularly remarkable development since at that time fusion and thermonuclear energy, and even that stars are largely composed of hydrogen (see metallicity), had not yet been discovered.

In 1925 Cecilia Helena Payne (later Cecilia Payne-Gaposchkin) wrote an influential doctoral dissertation at Radcliffe College, in which she applied Saha's ionization theory to stellar atmospheres to relate the spectral classes to the temperature of stars. Most significantly, she discovered that hydrogen and helium were the principal components of stars, not the composition of Earth. Despite Eddington's suggestion, discovery was so unexpected that her dissertation readers (including Russell) convinced her to modify the conclusion before publication. However, later research confirmed her discovery.

By the end of the 20th century, studies of astronomical spectra had expanded to cover wavelengths extending from radio waves through optical, x-ray, and gamma wavelengths. In the 21st century, it further expanded to include observations based on gravitational waves.

Observational astrophysics

Observational astronomy is a division of the astronomical science that is concerned with recording and interpreting data, in contrast with theoretical astrophysics, which is mainly concerned with finding out the measurable implications of physical models. It is the practice of observing celestial objects by using telescopes and other astronomical apparatus.

Most astrophysical observations are made using the electromagnetic spectrum.

* Radio astronomy studies radiation with a wavelength greater than a few millimeters. Example areas of study are radio waves, usually emitted by cold objects such as interstellar gas and dust clouds; the cosmic microwave background radiation which is the redshifted light from the Big Bang; pulsars, which were first detected at microwave frequencies. The study of these waves requires very large radio telescopes.

* Infrared astronomy studies radiation with a wavelength that is too long to be visible to the naked eye but is shorter than radio waves. Infrared observations are usually made with telescopes similar to the familiar optical telescopes. Objects colder than stars (such as planets) are normally studied at infrared frequencies.

* Optical astronomy was the earliest kind of astronomy. Telescopes paired with a charge-coupled device or spectroscopes are the most common instruments used. The Earth's atmosphere interferes somewhat with optical observations, so adaptive optics and space telescopes are used to obtain the highest possible image quality. In this wavelength range, stars are highly visible, and many chemical spectra can be observed to study the chemical composition of stars, galaxies, and nebulae.

* Ultraviolet, X-ray and gamma ray astronomy study very energetic processes such as binary pulsars, black holes, magnetars, and many others. These kinds of radiation do not penetrate the Earth's atmosphere well. There are two methods in use to observe this part of the electromagnetic spectrum—space-based telescopes and ground-based imaging air Cherenkov telescopes (IACT). Examples of Observatories of the first type are RXTE, the Chandra X-ray Observatory and the Compton Gamma Ray Observatory. Examples of IACTs are the High Energy Stereoscopic System (H.E.S.S.) and the MAGIC telescope.

Other than electromagnetic radiation, few things may be observed from the Earth that originate from great distances. A few gravitational wave observatories have been constructed, but gravitational waves are extremely difficult to detect. Neutrino observatories have also been built, primarily to study the Sun. Cosmic rays consisting of very high-energy particles can be observed hitting the Earth's atmosphere.

Observations can also vary in their time scale. Most optical observations take minutes to hours, so phenomena that change faster than this cannot readily be observed. However, historical data on some objects is available, spanning centuries or millennia. On the other hand, radio observations may look at events on a millisecond timescale (millisecond pulsars) or combine years of data (pulsar deceleration studies). The information obtained from these different timescales is very different.

The study of the Sun has a special place in observational astrophysics. Due to the tremendous distance of all other stars, the Sun can be observed in a kind of detail unparalleled by any other star. Understanding the Sun serves as a guide to understanding of other stars.

The topic of how stars change, or stellar evolution, is often modeled by placing the varieties of star types in their respective positions on the Hertzsprung–Russell diagram, which can be viewed as representing the state of a stellar object, from birth to destruction.

Theoretical astrophysics

Theoretical astrophysicists use a wide variety of tools which include analytical models (for example, polytropes to approximate the behaviors of a star) and computational numerical simulations. Each has some advantages. Analytical models of a process are generally better for giving insight into the heart of what is going on. Numerical models can reveal the existence of phenomena and effects that would otherwise not be seen.

Theorists in astrophysics endeavor to create theoretical models and figure out the observational consequences of those models. This helps allow observers to look for data that can refute a model or help in choosing between several alternate or conflicting models.

Theorists also try to generate or modify models to take into account new data. In the case of an inconsistency, the general tendency is to try to make minimal modifications to the model to fit the data. In some cases, a large amount of inconsistent data over time may lead to total abandonment of a model.

Topics studied by theoretical astrophysicists include stellar dynamics and evolution; galaxy formation and evolution; magnetohydrodynamics; large-scale structure of matter in the universe; origin of cosmic rays; general relativity and physical cosmology, including string cosmology and astroparticle physics. Relativistic astrophysics serves as a tool to gauge the properties of large-scale structures for which gravitation plays a significant role in physical phenomena investigated and as the basis for black hole (astro)physics and the study of gravitational waves.

Some widely accepted and studied theories and models in astrophysics, now included in the Lambda-CDM model, are the Big Bang, cosmic inflation, dark matter, dark energy and fundamental theories of physics.

Popularization

The roots of astrophysics can be found in the seventeenth century emergence of a unified physics, in which the same laws applied to the celestial and terrestrial realms. There were scientists who were qualified in both physics and astronomy who laid the firm foundation for the current science of astrophysics. In modern times, students continue to be drawn to astrophysics due to its popularization by the Royal Astronomical Society and notable educators such as prominent professors Lawrence Krauss, Subrahmanyan Chandrasekhar, Stephen Hawking, Hubert Reeves, Carl Sagan and Patrick Moore. The efforts of the early, late, and present scientists continue to attract young people to study the history and science of astrophysics. The television sitcom show The Big Bang Theory popularized the field of astrophysics with the general public, and featured some well known scientists like Stephen Hawking and Neil deGrasse Tyson.

Additional Information

The branch of astronomy called astrophysics is a new approach to an ancient field. For centuries astronomers studied the movements and interactions of the sun, the moon, planets, stars, comets, and meteors. Advances in technology have made it possible for scientists to study their properties and structure. Astrophysicists collect particles from meteorites and use telescopes on land, in balloons, and in satellites to gather data. They apply chemical and physical laws to explore what celestial objects consist of and how they formed and evolved.

Spectroscopy and photography, adopted for astronomical research in the 19th century, let investigators measure the quantity and quality of light emitted by stars and nebulas (clouds of interstellar gas and dust). That allowed them to study the brightness, temperature, and chemical composition of such objects in space. Investigators soon recognized that the properties of all celestial bodies, including the planets of the solar system, could only be understood in terms of what goes on inside and around them. The trend toward using physics and chemistry to interpret celestial observations gained momentum in the early 1920s, and many astronomers began referring to themselves as astrophysicists. Since the 1960s the field has developed more rapidly.

The major areas of current interest—X-ray astronomy, gamma-ray astronomy, infrared astronomy, and radio astronomy— depend heavily on engineering for the construction of telescopes, space probes, and related equipment. The scope of both observation and theory has expanded greatly because of such technological advances as electronic radar and radio units, high-speed computers, electronic radiation detectors, Earth-orbiting observatories, and long-range planetary probes.

It appears to me that if one wants to make progress in mathematics, one should study the masters and not the pupils. - Niels Henrik Abel.

Nothing is better than reading and gaining more and more knowledge - Stephen William Hawking.

Offline

#2453 2025-02-07 16:30:17

- Jai Ganesh

- Administrator

- Registered: 2005-06-28

- Posts: 52,770

Re: Miscellany

2352) Catering/Catering Technology

Gist

Catering technology can be defined as 'the application of science to the art of catering'. For this purpose catering is taken to mean the feeding of people in large groups and includes restaurants, hotels, work canteens, schools meals and hospitals as well as take-away meals such as fish and chip shops.

Summary

Before you consider starting a catering business, it is crucial to understand the types of catering and what is catering. Knowing the basic concepts of catering will help you run a successful catering business, be a better caterer and draft your catering business plan.

So, what is catering? First, let’s review all you need to know about catering business basics and the types of catering.

What Is Catering?

Catering is the process or business of preparing food and providing food services for clients at remote locations, such as hotels, restaurants, offices, concerts, and events. Companies that offer food, drinks, and other services to various customers, typically for special occasions, make up the catering sector.

Some restaurant businesses may contract their cooking to catering businesses or even offer catering services to customers. For instance, customers may love a particular dish so much that they want the same food to be served at their event.

Catering is more than just preparing food and cleaning up after the party. Sometimes, catering branches into event planning and management. For example, if you offer corporate catering services, you will be required to work with large crowds and handle the needs of corporate clients.

A catering business may use its chefs to create food or buy food from a vendor or third party to deliver to the client. In addition, you may be asked to plan the food menu for corporate events such as picnics, holiday celebrations, and other functions. So, what is a caterer? Let’s find out.

What Is a Caterer?

A caterer is a person or business that prepares, cooks, and serves food and beverages to clients at remote locations and events. The caterer may be asked to prepare seasonal menu options and provide the equipment such as dishes, spoons, place settings, and wine glasses needed to serve guests at an event.

Starting a catering business is the ideal venture for you if you enjoy interacting with guests and producing a wide range of dishes that are delicious to eat as well as beautiful to look at. A caterer is inventive in novel recipes, culinary presentations, and menus.

In addition, caterers excel at multitasking. For instance, if professional wait staff will be serving each course of dinner to guests, the caterer must be ready to prepare all the dishes for the event at once.

To ensure attendees enjoy their time at events, caterers always offer a delicious, relaxing dinner. Additionally, caterers may deal with particular demands and design menus for unique events directly with clients.

Usually, a catering service sends waiters, waitresses, and busboys to set tables and serve meals during sit-down dining occasions. The caterer may send staff to prepare chafing dishes, bowls, and platters filled with food for buffets and casual gatherings, replace them, and serve food to guests.

4 Types of Catering

It is essential to choose a catering specialty when starting your catering business. With many catering types to choose from, it’s only logical to research your options and pick a niche that will suit your target market and improve your unique selling proposition.

Let’s look at the types of catering:

What Is Event Catering?

Event catering is planning a menu, preparing, delivering, and serving food at social events and parties. Catering is an integral part of any event.

As you know, events revolve around the food and drink menu. Party guests may even say that the success of any event depends on the catering services.

Birthday celebrations, retirement parties, grand openings, housewarming parties, weddings, and baby showers are a few exceptional events that fall under this category. In addition, catering packages for event catering sometimes include things like appetizers, decorations, bartenders, and servers.

Types of Event Catering

* Stationary Platters

* Hors D’oeuvres

* Small Plates and Stations

* Three-Course Plated Dinner

* Buffet

* Outdoor BBQ

What Is Full-Service Catering?

Full-service catering manages every facet of an event, including meal preparation, decorations, and clean-up following the event. Unlike regular event catering, where the caterer just prepares and serves food and drinks, a full-service caterer handles every event detail based on clients' specifications.

Some logistics, such as dinnerware, linens, serving utensils, and dedicated staff to help on-site, are handled by full-service catering. The head caterer oversees every aspect of the event according to what will appeal to each guest.

What Does a Full-service Catering Business Offer?

* Venue setup

* Menu planning

* Dining setup

* Food preparation

* After-party cleanup.

Details

Catering is the business of providing food services at a remote site or a site such as a hotel, hospital, pub, aircraft, cruise ship, park, festival, filming location or film studio.

History of catering

The earliest account of major services being catered in the United States was an event for William Howe of Philadelphia in 1778. The event served local foods that were a hit with the attendees, who eventually popularized catering as a career. The official industry began to be recognized around the 1820’s, with the caterers being disproportionately African-American. The catering business began to form around 1820, centered in Philadelphia.

Robert Bogle

The industry began to professionalize under the reigns of Robert Bogle who is recognized as "the originator of catering." Catering was originally done by servants of wealthy elites. Butlers and house slaves, which were often black, were in a good position to become caterers. Essentially, caterers in the 1860s were "public butlers" as they organized and executed the food aspect of a social gathering. A public butler was a butler working for several households. Bogle took on the role of public butler and took advantage of the food service market in the hospitality field.

Caterers like Bogle were involved with events likely to be catered today, such as weddings and funerals. Bogle also is credited with creating the Guild of Caterers and helping train other black caterers. This is important because catering provided not only jobs to black people but also opportunities to connect with elite members of Philadelphia society. Over time, the clientele of caterers became the middle class, who could not afford lavish gatherings and increasing competition from white caterers led to a decline in black catering businesses.

Evolution of catering

By the 1840s many restaurant owners began to combine catering services with their shops. Second-generation caterers grew the industry on the East Coast, becoming more widespread. Common usage of the word "caterer" came about in the 1880s at which point local directories began to use these term to describe the industry. White businessmen took over the industry by the 1900’s, with the Black Catering population disappearing.

In the 1930s, the Soviet Union, creating more simple menus, began developing state public catering establishments as part of its collectivization policies. A rationing system was implemented during World War II, and people became used to public catering. After the Second World War, many businessmen embraced catering as an alternative way of staying in business after the war. By the 1960s, the home-made food was overtaken by eating in public catering establishments.

By the 2000s, personal chef services started gaining popularity, with more women entering the workforce.[citation needed] People between 15 and 24 years of age spent as little as 11–17 minutes daily on food preparation and clean-up activities in 2006-2016, according to figures revealed by the American Time Use Survey conducted by the US Bureau of Labor Statistics. There are many types of catering, including Event catering, Wedding Catering and Corporate Catering.

Event catering

An event caterer serves food at indoor and outdoor events, including corporate and workplace events and parties at home and venues.

Mobile catering

A mobile caterer serves food directly from a vehicle, cart or truck which is designed for the purpose. Mobile catering is common at outdoor events such as concerts, workplaces, and downtown business districts. Mobile catering services require less maintenance costs when compared with other catering services. Mobile caterers may also be known as food trucks in some areas. Mobile catering is popular throughout New York City, though sometimes can be unprofitable. Ice cream vans are a familiar example of a catering truck in Canada, the United States and the United Kingdom.

Seat-back catering

Seat-back catering was a service offered by some charter airlines in the United Kingdom (e.g., Court Line, which introduced the idea in the early 1970s, and Dan-Air) that involved embedding two meals in a single seat-back tray. "One helping was intended for each leg of a charter flight, but Alan Murray, of Viking Aviation, had earlier revealed that 'with the ingenious use of a nail file or coin, one could open the inbound meal and have seconds'. The intention of participating airlines was to "save money, reduce congestion in the cabin and give punters the chance to decide when to eat their meal". By requiring less galley space on board, the planes could offer more passenger seats.

According to TravelUpdate's columnist, "The Flight Detective", "Salads and sandwiches were the usual staples," and "a small pellet of dry ice was put into the compartment for the return meal to try to keep it fresh." However, in addition to the fact that passengers on one leg were able to consume the food intended for other passengers on the following leg, there was a "food hygiene" problem, and the concept was discontinued by 1975.

Canapé catering

A canapé caterer serves canapés at events. They have become a popular type of food at events, Christmas parties and weddings. A canapé is a type of hors d'oeuvre, a small, prepared, and often decorative food, consisting of a small piece of bread or pastry. They should be easier to pick up and not be bigger than one or two bites. The bite-sized food is usually served before the starter or main course or alone with drinks at a drinks party.

Wedding catering

A wedding caterer provides food for a wedding reception and party, traditionally called a wedding breakfast. A wedding caterer can be hired independently or can be part of a package designed by the venue. Catering service providers are often skilled and experienced in preparing and serving high-quality cuisine. They offer a diverse and rich selection of food, creating a great experience for their customers. There are many different types of wedding caterers, each with their approach to food.

Shipboard catering

Merchant ships – especially ferries, cruise liners, and large cargo ships – often carry Catering Officers. In fact, the term "catering" was in use in the world of the merchant marine long before it became established as a land-bound business.

It appears to me that if one wants to make progress in mathematics, one should study the masters and not the pupils. - Niels Henrik Abel.

Nothing is better than reading and gaining more and more knowledge - Stephen William Hawking.

Offline

#2454 2025-02-08 00:03:31

- Jai Ganesh

- Administrator

- Registered: 2005-06-28

- Posts: 52,770

Re: Miscellany

2353) Bun

Gist

A bun is a type of bread roll, typically filled with savory fillings (for example hamburger). A bun may also refer to a sweet cake in certain parts of the world. Though they come in many shapes and sizes, buns are most commonly round, and are generally hand-sized or smaller.

Summary:

Ingredient List

For the food processor buns:

* 3 cups bread or all-purpose flour (may be part whole wheat flour)

* 2 tablespoons granulated sugar

* 1 teaspoon salt

* 1 (¼ ounce) package instant yeast

* 3 tablespoons unsalted butter or margarine, cubed

* 1 cup lukewarm water (90°F)

Instructions

For the food processor buns:

In bowl of food processor fitted with dough blade, add flour, sugar, salt, yeast and butter. Place lid on processor and pulse 10 seconds.

Begin processing, pouring 1 cup warm water through tube. When dough forms a ball, stop adding water. All may not be needed. Process dough an additional 60 seconds to knead.

Remove dough and smooth into a ball; cover with bowl and let rest 15 minutes.

Divide dough into 8 buns and flatten into 3 ½” disks. Place buns two inches apart on greased or parchment-lined baking sheet. Cover; let rise in a warm place until doubled. Near the end of the rise, preheat oven to 400°F.

Bake 12 – 15 minutes, until golden and internal temperature registers 190°F – 195°F. Remove buns to rack and cool before slicing.

Nutrition Information Per Serving (1 Bun, 91g): 240 calories, 45 calories from fat, 5g total fat, 3g saturated fat, 0g trans fat, 10mg cholesterol, 300mg sodium, 41g total carbohydrate, 1g dietary fiber, 3g sugars, 7g protein, 97mcg folate, 2mg vitamin C, 2mg iron.

Details

A bun is a type of bread roll, typically filled with savory fillings (for example hamburger). A bun may also refer to a sweet cake in certain parts of the world. Though they come in many shapes and sizes, buns are most commonly round, and are generally hand-sized or smaller.

In the United Kingdom, the usage of the term differs greatly in different regions. In Southern England, a bun is a hand-sized sweet cake, while in Northern England, it is a small round of ordinary bread. In Ireland, a bun refers to a sweet cake, roughly analogous to an American cupcake.

Buns are usually made from a dough of flour, milk, yeast and small amounts of sugar and/or butter. Sweet bun dough is distinguished from bread dough by the addition of sugar, butter and sometimes egg. Common sweet varieties contain small fruit or nuts, topped with icing or caramel, and filled with jam or cream.

Chinese baozi, with savory or sweet fillings, are often referred to as "buns" in English.

Additional Information:

How to Make Hamburger Buns

It couldn't be easier to make these homemade hamburger buns. You'll find the step-by-step recipe below — but here's a brief overview of what you can expect:

* Make the dough.

* Let the dough rise.

* Form the buns.

* Bake the buns, then let them cool completely.

* Slice the buns in half lengthwise.

Begin by proofing the yeast with some of the flour. Once the yeast is foamy, add the remaining flour, an egg, butter, sugar, and salt. Fit a stand mixer with a dough hook and knead the dough, scraping the sides often, until it's soft and sticky.

Transfer the dough to a floured surface and form into a smooth, round ball. Tuck the ends underneath and return the dough to an oil-drizzled stand mixer bowl. Ensure the dough is coated with oil, then cover and allow to rise in a warm place until it has doubled in size.

Transfer the dough back to the floured work surface. Pat into a slightly rounded rectangle, then cut into eight equal squares. Use your hands to shape and pat the squares into discs. Arrange the buns on a floured baking sheet, cover, and let rise until they've doubled in size.

Brush the buns with an egg wash and sprinkle with sesame seeds. Bake in a preheated oven until lightly browned. Remove from the oven, allow the buns to cool, and slice in half lengthwise to serve.

How to Store Hamburger Buns

Store the homemade hamburger buns in an airtight container or wrapped in foil at room temperature for up to five days. Avoid short term refrigeration, as this will dry them out.

Can You Freeze Hamburger Buns?

Yes, you can freeze homemade hamburger buns (though they're best enjoyed fresh). Transfer the cooled buns to a freezer-safe container, then wrap in a layer of foil. Label with the date and freeze for up to two months. Thaw on a paper towel at room temperature. When it's about halfway thawed, flip the bun, and replace the paper towel.

Allrecipes Community Tips and Praise

"This recipe was so simple and fun to make," according to Kris Allfrey. "The hamburger buns were so light and the crumb texture was perfect. I followed the recipe and Chef John's instructions to the letter. I wouldn't change a thing about this recipe. They are excellent for pulled-pork sandwiches."

"I didn't make any changes except for what I put on top of the buns. I put dried onion, parsley, sesame seeds, and poppy seeds," says Ron Doty-Tolaro. "Also, as a rule of thumb, when making any kind of rising bread, lightly push in on the dough with one finger. If the dough is ready it will bounce back out. If the indentation stays in, knead it more."

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/AR-6761-tasty-buns-DDMFS-4x3-87727702d7944a07897f59ba6d3ab21d.jpg)

It appears to me that if one wants to make progress in mathematics, one should study the masters and not the pupils. - Niels Henrik Abel.

Nothing is better than reading and gaining more and more knowledge - Stephen William Hawking.

Offline

#2455 2025-02-08 20:04:00

- Jai Ganesh

- Administrator

- Registered: 2005-06-28

- Posts: 52,770

Re: Miscellany

2354) Hypertension

Gist

Hypertension (high blood pressure) is when the pressure in your blood vessels is too high (140/90 mmHg or higher). It is common but can be serious if not treated. People with high blood pressure may not feel symptoms. The only way to know is to get your blood pressure checked.

Summary

High blood pressure (also called hypertension) can lead to serious problems like heart attacks or strokes. But lifestyle changes and blood pressure medicines can help you stay healthy.

Check if you're at risk of high blood pressure

High blood pressure is very common, especially in older adults. There are usually no symptoms, so you may not realise you have it.

Things that increase your chances of having high blood pressure include:

* your age – you're more likely to get high blood pressure as you get older

* having close relatives with high blood pressure

* your ethnicity – you're at higher risk if you have a Black African, Black Caribbean or South Asian ethnic background

* having an unhealthy diet – especially a diet that's high in salt

* being overweight

* smoking

* drinking too much alcohol

* feeling stressed over a long period

Non-urgent advice:Get your blood pressure checked at a pharmacy or GP surgery if:

* you think you might have high blood pressure or might be at risk of having high blood pressure

* you're aged 40 or over and have not had your blood pressure checked for more than 5 years.

Some pharmacies may charge for a blood pressure check.

Some workplaces also offer blood pressure checks. Check with your employer.

Symptoms of high blood pressure

High blood pressure does not usually cause any symptoms.

Many people have it without realising it.

Rarely, high blood pressure can cause symptoms such as:

* headaches

* blurred vision

* chest pain

But the only way to find out if you have high blood pressure is to get your blood pressure checked.

Details

Hypertension, also known as high blood pressure, is a long-term medical condition in which the blood pressure in the arteries is persistently elevated. High blood pressure usually does not cause symptoms itself. It is, however, a major risk factor for stroke, coronary artery disease, heart failure, atrial fibrillation, peripheral arterial disease, vision loss, chronic kidney disease, and dementia. Hypertension is a major cause of premature death worldwide.

High blood pressure is classified as primary (essential) hypertension or secondary hypertension. About 90–95% of cases are primary, defined as high blood pressure due to nonspecific lifestyle and genetic factors. Lifestyle factors that increase the risk include excess salt in the diet, excess body weight, smoking, physical inactivity and alcohol use. The remaining 5–10% of cases are categorized as secondary hypertension, defined as high blood pressure due to a clearly identifiable cause, such as chronic kidney disease, narrowing of the kidney arteries, an endocrine disorder, or the use of birth control pills.

Blood pressure is classified by two measurements, the systolic (first number) and diastolic (second number) pressures. For most adults, normal blood pressure at rest is within the range of 100–140 millimeters mercury (mmHg) systolic and 60–90 mmHg diastolic. For most adults, high blood pressure is present if the resting blood pressure is persistently at or above 130/80 or 140/90 mmHg. Different numbers apply to children. Ambulatory blood pressure monitoring over a 24-hour period appears more accurate than office-based blood pressure measurement.

Lifestyle changes and medications can lower blood pressure and decrease the risk of health complications. Lifestyle changes include weight loss, physical exercise, decreased salt intake, reducing alcohol intake, and a healthy diet. If lifestyle changes are not sufficient, blood pressure medications are used. Up to three medications taken concurrently can control blood pressure in 90% of people. The treatment of moderately high arterial blood pressure (defined as >160/100 mmHg) with medications is associated with an improved life expectancy. The effect of treatment of blood pressure between 130/80 mmHg and 160/100 mmHg is less clear, with some reviews finding benefit and others finding unclear benefit. High blood pressure affects 33% of the population globally. About half of all people with high blood pressure do not know that they have it. In 2019, high blood pressure was believed to have been a factor in 19% of all deaths (10.4 million globally).

Signs and symptoms

Hypertension is rarely accompanied by symptoms. Half of all people with hypertension are unaware that they have it. Hypertension is usually identified as part of health screening or when seeking healthcare for an unrelated problem.

Some people with high blood pressure report headaches, as well as lightheadedness, vertigo, tinnitus (buzzing or hissing in the ears), altered vision or fainting episodes. These symptoms, however, might be related to associated anxiety rather than the high blood pressure itself.

Long-standing untreated hypertension can cause organ damage with signs such as changes in the optic fundus seen by ophthalmoscopy. The severity of hypertensive retinopathy correlates roughly with the duration or the severity of the hypertension. Other hypertension-caused organ damage include chronic kidney disease and thickening of the heart muscle.

Secondary hypertension

Secondary hypertension is hypertension due to an identifiable cause, and may result in certain specific additional signs and symptoms. For example, as well as causing high blood pressure, Cushing's syndrome frequently causes truncal obesity, glucose intolerance, moon face, a hump of fat behind the neck and shoulders (referred to as a buffalo hump), and purple abdominal stretch marks. Hyperthyroidism frequently causes weight loss with increased appetite, fast heart rate, bulging eyes, and tremor. Renal artery stenosis may be associated with a localized abdominal bruit to the left or right of the midline, or in both locations. Coarctation of the aorta frequently causes a decreased blood pressure in the lower extremities relative to the arms, or delayed or absent femoral arterial pulses. Pheochromocytoma may cause abrupt episodes of hypertension accompanied by headache, palpitations, pale appearance, and excessive sweating.

Hypertensive crisis

Severely elevated blood pressure (equal to or greater than a systolic 180 mmHg or diastolic of 120 mmHg) is referred to as a hypertensive crisis. Hypertensive crisis is categorized as either hypertensive urgency or hypertensive emergency, according to the absence or presence of end organ damage, respectively.

In hypertensive urgency, there is no evidence of end organ damage resulting from the elevated blood pressure. In these cases, oral medications are used to lower the BP gradually over 24 to 48 hours.

In hypertensive emergency, there is evidence of direct damage to one or more organs. The most affected organs include the brain, kidney, heart and lungs, producing symptoms which may include confusion, drowsiness, chest pain and breathlessness. In hypertensive emergency, the blood pressure must be reduced more rapidly to stop ongoing organ damage; however, there is a lack of randomized controlled trial evidence for this approach.

Pregnancy

Hypertension occurs in approximately 8–10% of pregnancies. Two blood pressure measurements six hours apart of greater than 140/90 mmHg are diagnostic of hypertension in pregnancy. High blood pressure in pregnancy can be classified as pre-existing hypertension, gestational hypertension, or pre-eclampsia. Women who have chronic hypertension before their pregnancy are at increased risk of complications such as premature birth, low birthweight or stillbirth. Women who have high blood pressure and had complications in their pregnancy have three times the risk of developing cardiovascular disease compared to women with normal blood pressure who had no complications in pregnancy.

Pre-eclampsia is a serious condition of the second half of pregnancy and following delivery characterised by increased blood pressure and the presence of protein in the urine. It occurs in about 5% of pregnancies and is responsible for approximately 16% of all maternal deaths globally. Pre-eclampsia also doubles the risk of death of the baby around the time of birth. Usually there are no symptoms in pre-eclampsia and it is detected by routine screening. When symptoms of pre-eclampsia occur the most common are headache, visual disturbance (often "flashing lights"), vomiting, pain over the stomach, and swelling. Pre-eclampsia can occasionally progress to a life-threatening condition called eclampsia, which is a hypertensive emergency and has several serious complications including vision loss, brain swelling, seizures, kidney failure, pulmonary edema, and disseminated intravascular coagulation (a blood clotting disorder).

In contrast, gestational hypertension is defined as new-onset hypertension during pregnancy without protein in the urine.

There have been significant findings on how exercising can help reduce the effects of hypertension just after one bout of exercise. Exercising can help reduce hypertension as well as pre-eclampsia and eclampsia.

The acute physiological responses include an increase in cardiac output (CO) of the individual (increased heart rate and stroke volume). This increase in CO can inadvertently maintain the amount of blood going into the muscles, improving functionality of the muscle later. Exercising can also improve systolic and diastolic blood pressure making it easier for blood to pump to the body. Through regular bouts of physical activity, blood pressure can reduce the incidence of hypertension.

Aerobic exercise has been shown to regulate blood pressure more effectively than resistance training. It is recommended to see the effects of exercising, that a person should aim for 5-7 days/ week of aerobic exercise. This type of exercise should have an intensity of light to moderate, utilizing ~85% of max heart rate (220-age). Aerobic has shown a decrease in SBP by 5-15mmHg, versus resistance training showing a decrease of only 3-5mmHg. Aerobic exercises such as jogging, rowing, dancing, or hiking can decrease SBP the greatest. The decrease in SBP can regulate the effect of hypertension ensuring the baby will not be harmed. Resistance training takes a toll on the cardiovascular system in untrained individuals, leading to a reluctance in prescription of resistance training for hypertensive reduction purposes.

Children

Failure to thrive, seizures, irritability, lack of energy, and difficulty in breathing can be associated with hypertension in newborns and young infants. In older infants and children, hypertension can cause headache, unexplained irritability, fatigue, failure to thrive, blurred vision, nosebleeds, and facial paralysis.

Causes:

Primary hypertension

Primary (also termed essential) hypertension results from a complex interaction of genes and environmental factors. More than 2000 common genetic variants with small effects on blood pressure have been identified in association with high blood pressure, as well as some rare genetic variants with large effects on blood pressure. There is also evidence that DNA methylation at multiple nearby CpG sites may link some sequence variation to blood pressure, possibly via effects on vascular or renal function.

Blood pressure rises with aging in societies with a western diet and lifestyle, and the risk of becoming hypertensive in later life is substantial in most such societies. Several environmental or lifestyle factors influence blood pressure. Reducing dietary salt intake lowers blood pressure; as does weight loss, exercise training, vegetarian diets, increased dietary potassium intake and high dietary calcium supplementation. Increasing alcohol intake is associated with higher blood pressure, but the possible roles of other factors such as caffeine consumption, and vitamin D deficiency are less clear. Average blood pressure is higher in the winter than in the summer.

Depression is associated with hypertension and loneliness is also a risk factor. Periodontal disease is also associated with high blood pressure. Chemical element As exposure through drinking water is associated with elevated blood pressure. Air pollution is associated with hypertension. Whether these associations are causal is unknown. Gout and elevated blood uric acid are associated with hypertension and evidence from genetic (Mendelian Randomization) studies and clinical trials indicate this relationship is likely to be causal. Insulin resistance, which is common in obesity and is a component of syndrome X (or metabolic syndrome), can cause hyperuricemia and gout and is also associated with elevated blood pressure.

Events in early life, such as low birth weight, maternal smoking, and lack of breastfeeding may be risk factors for adult essential hypertension, although strength of the relationships is weak and the mechanisms linking these exposures to adult hypertension remain unclear.

Secondary hypertension

Secondary hypertension results from an identifiable cause. Kidney disease is the most common secondary cause of hypertension. Hypertension can also be caused by endocrine conditions, such as Cushing's syndrome, hyperthyroidism, hypothyroidism, acromegaly, Conn's syndrome or hyperaldosteronism, renal artery stenosis (from atherosclerosis or fibromuscular dysplasia), hyperparathyroidism, and pheochromocytoma. Other causes of secondary hypertension include obesity, sleep apnea, pregnancy, coarctation of the aorta, excessive eating of liquorice, excessive drinking of alcohol, certain prescription medicines, herbal remedies, and stimulants such as cocaine and methamphetamine.

A 2018 review found that any alcohol increased blood pressure in males while over one or two drinks increased the risk in females.

Additional Information

Hypertension is a condition that arises when the blood pressure is abnormally high. Hypertension occurs when the body’s smaller blood vessels (the arterioles) narrow, causing the blood to exert excessive pressure against the vessel walls and forcing the heart to work harder to maintain the pressure. Although the heart and blood vessels can tolerate increased blood pressure for months and even years, eventually the heart may enlarge (a condition called hypertrophy) and be weakened to the point of failure. Injury to blood vessels in the kidneys, brain, and eyes also may occur.

Blood pressure is actually a measure of two pressures, the systolic and the diastolic. The systolic pressure (the higher pressure and the first number recorded) is the force that blood exerts on the artery walls as the heart contracts to pump the blood to the peripheral organs and tissues. The diastolic pressure (the lower pressure and the second number recorded) is residual pressure exerted on the arteries as the heart relaxes between beats. A diagnosis of hypertension is made when blood pressure reaches or exceeds 140/90 mmHg (read as “140 over 90 millimeters of mercury”).

Classification

When there is no demonstrable underlying cause of hypertension, the condition is classified as essential hypertension. (Essential hypertension is also called primary or idiopathic hypertension.) This is by far the most common type of high blood pressure, occurring in 90 to 95 percent of patients. Genetic factors appear to play a major role in the occurrence of essential hypertension. Secondary hypertension is associated with an underlying disease, which may be renal, neurologic, or endocrine in origin; examples of such diseases include Bright disease (glomerulonephritis; inflammation of the urine-producing structures in the kidney), atherosclerosis of blood vessels in the brain, and Cushing syndrome (hyperactivity of the adrenal glands). In cases of secondary hypertension, correction of the underlying cause may cure the hypertension. Various external agents also can raise blood pressure. These include cocaine, amphetamines, cold remedies, thyroid supplements, corticosteroids, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), and oral contraceptives.

Malignant hypertension is present when there is a sustained or sudden rise in diastolic blood pressure exceeding 120 mmHg, with accompanying evidence of damage to organs such as the eyes, brain, heart, and kidneys. Malignant hypertension is a medical emergency and requires immediate therapy and hospitalization.

Epidemiology

Elevated arterial pressure is one of the most important public health problems in developed countries. In the United States, for instance, nearly 30 percent of the adult population is hypertensive. High blood pressure is significantly more prevalent and serious among African Americans. Age, race, sex, smoking, alcohol intake, elevated serum cholesterol, salt intake, glucose intolerance, obesity, and stress all may contribute to the degree and prognosis of the disease. In both men and women, the risk of developing high blood pressure increases with age.

Hypertension has been called the “silent killer” because it usually produces no symptoms. It is important, therefore, for anyone with risk factors to have their blood pressure checked regularly and to make appropriate lifestyle changes.

Complications

The most common immediate cause of hypertension-related death is heart disease, but death from stroke or renal (kidney) failure is also frequent. Complications result directly from the increased pressure (cerebral hemorrhage, retinopathy, left ventricular hypertrophy, congestive heart failure, arterial aneurysm, and vascular rupture), from atherosclerosis (increased coronary, cerebral, and renal vascular resistance), and from decreased blood flow and ischemia (myocardial infarction, cerebral thrombosis and infarction, and renal nephrosclerosis). The risk of developing many of these complications is greatly elevated when hypertension is diagnosed in young adulthood.

Treatment

Effective treatment will reduce overall cardiovascular morbidity and mortality. Nondrug therapy consists of: (1) relief of stress, (2) dietary management (restricted intake of salt, calories, cholesterol, and saturated fats; sufficient intake of potassium, magnesium, calcium, and vitamin C), (3) regular aerobic exercise, (4) weight reduction, (5) smoking cessation, and (6) reduced intake of alcohol and caffeine.

Mild to moderate hypertension may be controlled by a single-drug regimen, although more severe cases often require a combination of two or more drugs. Diuretics are a common medication; these agents lower blood pressure primarily by reducing body fluids and thereby reducing peripheral resistance to blood flow. However, they deplete the body’s supply of potassium, so it is recommended that potassium supplements be added or that potassium-sparing diuretics be used. Beta-adrenergic blockers (beta-blockers) block the effects of epinephrine (adrenaline), thus easing the heart’s pumping action and widening blood vessels. Vasodilators act by relaxing smooth muscle in the walls of blood vessels, allowing small arteries to dilate and thereby decreasing total peripheral resistance. Calcium channel blockers promote peripheral vasodilation and reduce vascular resistance. Angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors inhibit the generation of a potent vasoconstriction agent (angiotensin II), and they also may retard the degradation of a potent vasodilator (bradykinin) and involve the synthesis of vasodilatory prostaglandins. Angiotensin receptor antagonists are similar to ACE inhibitors in utility and tolerability, but instead of blocking the production of angiotensin II, they completely inhibit its binding to the angiotensin II receptor. Statins, best known for their use as cholesterol-lowering agents, have shown promise as antihypertensive drugs because of their ability to lower both diastolic and systolic blood pressure. The mechanism by which statins act to reduce blood pressure is unknown; however, scientists suspect that these drugs activate substances involved in vasodilation.

Other agents that may be used in the treatment of hypertension include the antidiabetic drug semaglutide and the drug aprocitentan. Semaglutide is used specifically in patients who are obese or overweight. The drug acts as a glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) receptor agonist; GLP-1 interacts with receptors in the brain involved in the regulation of appetite, and thus semaglutide effectively triggers a reduction in appetite and thereby helps relieve symptoms of weight-related complications, such as hypertension. Aprocitentan acts as an inhibitor at endothelin A and endothelin B receptors, preventing binding by endothelin-1, which is a key protein involved in the activation of vasoconstriction and inflammatory processes in blood vessels.

It appears to me that if one wants to make progress in mathematics, one should study the masters and not the pupils. - Niels Henrik Abel.

Nothing is better than reading and gaining more and more knowledge - Stephen William Hawking.

Offline

#2456 2025-02-09 17:05:10

- Jai Ganesh

- Administrator

- Registered: 2005-06-28

- Posts: 52,770

Re: Miscellany

2355) Hypotension

Gist

Low blood pressure is a condition in which the force of the blood pushing against the artery walls is too low. It's also called hypotension. Blood pressure is measured in millimeters of mercury (mm Hg). In general, low blood pressure is a reading lower than 90/60 mm Hg.

Low blood pressure occurs when blood pressure is much lower than normal. This means the heart, brain, and other parts of the body may not get enough blood. Normal blood pressure is mostly between 90/60 mmHg and 120/80 mmHg. The medical word for low blood pressure is hypotension.

Summary

Hypotension, also known as low blood pressure, is a cardiovascular condition characterized by abnormally reduced blood pressure. Blood pressure is the force of blood pushing against the walls of the arteries as the heart pumps out blood and is indicated by two numbers, the systolic blood pressure (the top number) and the diastolic blood pressure (the bottom number), which are the maximum and minimum blood pressures within the cardiac cycle, respectively. A systolic blood pressure of less than 90 millimeters of mercury (mmHg) or diastolic of less than 60 mmHg is generally considered to be hypotension. Different numbers apply to children. However, in practice, blood pressure is considered too low only if noticeable symptoms are present.