Math Is Fun Forum

You are not logged in.

- Topics: Active | Unanswered

#326 Re: Jai Ganesh's Puzzles » 10 second questions » 2025-10-24 14:20:18

Hi,

#9774.

#327 Re: Jai Ganesh's Puzzles » Oral puzzles » 2025-10-24 14:10:50

Hi,

#6279.

#328 Re: Exercises » Compute the solution: » 2025-10-24 13:51:56

Hi,

2625.

#329 This is Cool » Radiography » 2025-10-23 18:05:19

- Jai Ganesh

- Replies: 0

Radiography

Gist

Radiography is a medical imaging technique that uses X-rays to create static images of the inside of the body to diagnose fractures, infections, or locate foreign objects. During the procedure, an X-ray beam is passed through the body, and the remaining radiation is captured on film or a digital detector to form an image. These images are used by doctors to visualize internal structures and aid in diagnosis and treatment planning.

It is used to diagnose or treat patients by recording images of the internal structure of the body to assess the presence or absence of disease, foreign objects, and structural damage or anomaly. During a radiographic procedure, an x-ray beam is passed through the body.

Summary

X-ray or radiography uses a very small dose of ionizing radiation to produce pictures of the body's internal structures. X-rays are the oldest and most frequently used form of medical imaging. They are often used to help diagnosed fractured bones, look for injury or infection and to locate foreign objects in soft tissue. Some x-ray exams may use an iodine-based contrast material or barium to help improve the visibility of specific organs, blood vessels, tissues or bone.

Details

Radiography is an imaging technique using X-rays, gamma rays, or similar ionizing radiation and non-ionizing radiation to view the internal form of an object. Applications of radiography include medical ("diagnostic" radiography and "therapeutic radiography") and industrial radiography. Similar techniques are used in airport security, (where "body scanners" generally use backscatter X-ray). To create an image in conventional radiography, a beam of X-rays is produced by an X-ray generator and it is projected towards the object. A certain amount of the X-rays or other radiation are absorbed by the object, dependent on the object's density and structural composition. The X-rays that pass through the object are captured behind the object by a detector (either photographic film or a digital detector). The generation of flat two-dimensional images by this technique is called projectional radiography. In computed tomography (CT scanning), an X-ray source and its associated detectors rotate around the subject, which itself moves through the conical X-ray beam produced. Any given point within the subject is crossed from many directions by many different beams at different times. Information regarding the attenuation of these beams is collated and subjected to computation to generate two-dimensional images on three planes (axial, coronal, and sagittal) which can be further processed to produce a three-dimensional image.

Industrial radiography

Industrial radiography is a method of non-destructive testing where many types of manufactured components can be examined to verify the internal structure and integrity of the specimen. Industrial Radiography can be performed utilizing either X-rays or gamma rays. Both are forms of electromagnetic radiation. The difference between various forms of electromagnetic energy is related to the wavelength. X and gamma rays have the shortest wavelength and this property leads to the ability to penetrate, travel through, and exit various materials such as carbon steel and other metals. Specific methods include industrial computed tomography.

Image quality

Image quality will depend on resolution and density. Resolution is the ability of an image to show closely spaced structure in the object as separate entities in the image while density is the blackening power of the image. Sharpness of a radiographic image is strongly determined by the size of the X-ray source. This is determined by the area of the electron beam hitting the anode. A large photon source results in more blurring in the final image and is worsened by an increase in image formation distance. This blurring can be measured as a contribution to the modulation transfer function of the imaging system.

Additional Information

X-ray, electromagnetic radiation of extremely short wavelength and high frequency, with wavelengths ranging from about {10}^{-8} to {10}^{-12} metre and corresponding frequencies from about {10}^{16} to {10}^{20} hertz (Hz).

X-rays are commonly produced by accelerating (or decelerating) charged particles; examples include a beam of electrons striking a metal plate in an X-ray tube and a circulating beam of electrons in a synchrotron particle accelerator or storage ring. In addition, highly excited atoms can emit X-rays with discrete wavelengths characteristic of the energy level spacings in the atoms. The X-ray region of the electromagnetic spectrum falls far outside the range of visible wavelengths. However, the passage of X-rays through materials, including biological tissue, can be recorded with photographic films and other detectors. The analysis of X-ray images of the body is an extremely valuable medical diagnostic tool.

X-rays are a form of ionizing radiation—when interacting with matter, they are energetic enough to cause neutral atoms to eject electrons. Through this ionization process the energy of the X-rays is deposited in the matter. When passing through living tissue, X-rays can cause harmful biochemical changes in genes, chromosomes, and other cell components. The biological effects of ionizing radiation, which are complex and highly dependent on the length and intensity of exposure, are still under active study (see radiation injury). X-ray radiation therapies take advantage of these effects to combat the growth of malignant tumours.

X-rays were discovered in 1895 by German physicist Wilhelm Konrad Röntgen while investigating the effects of electron beams (then called cathode rays) in electrical discharges through low-pressure gases. Röntgen uncovered a startling effect—namely, that a screen coated with a fluorescent material placed outside a discharge tube would glow even when it was shielded from the direct visible and ultraviolet light of the gaseous discharge. He deduced that an invisible radiation from the tube passed through the air and caused the screen to fluoresce. Röntgen was able to show that the radiation responsible for the fluorescence originated from the point where the electron beam struck the glass wall of the discharge tube. Opaque objects placed between the tube and the screen proved to be transparent to the new form of radiation; Röntgen dramatically demonstrated this by producing a photographic image of the bones of the human hand. His discovery of so-called Röntgen rays was met with worldwide scientific and popular excitement, and, along with the discoveries of radioactivity (1896) and the electron (1897), it ushered in the study of the atomic world and the era of modern physics.

Fundamental characteristics:

Wave nature

X-rays are a form of electromagnetic radiation; their basic physical properties are identical to those of the more familiar components of the electromagnetic spectrum—visible light, infrared radiation, and ultraviolet radiation. As with other forms of electromagnetic radiation, X-rays can be described as coupled waves of electric and magnetic fields traveling at the speed of light (about 300,000 km, or 186,000 miles, per second). Their characteristic wavelengths and frequencies can be demonstrated and measured through the interference effects that result from the overlap of two or more waves in space. X-rays also exhibit particle-like properties; they can be described as a flow of photons carrying discrete amounts of energy and momentum. This dual nature is a property of all forms of radiation and matter and is comprehensively described by the theory of quantum mechanics.

Though it was immediately suspected, following Röntgen’s discovery, that X-rays were a form of electromagnetic radiation, this proved very difficult to establish. X-rays are distinguished by their very short wavelengths, typically 1,000 times shorter than the wavelengths of visible light. Because of this, and because of the practical difficulties of producing and detecting the new form of radiation, the nature of X-rays was only gradually unraveled in the early decades of the 20th century.

In 1906 the British physicist Charles Glover Barkla first demonstrated the wave nature of X-rays by showing that they can be “polarized” by scattering from a solid. Polarization refers to the orientation of the oscillations in a transverse wave; all electromagnetic waves are transverse oscillations of electric and magnetic fields. The very short wavelengths of X-rays, hinted at in early diffraction studies in which the rays were passed through narrow slits, was firmly established in 1912 by the pioneering work of the German physicist Max von Laue and his students Walter Friedrich and Paul Knipping. Laue suggested that the ordered arrangements of atoms in crystals could serve as natural three-dimensional diffraction gratings. Typical atomic spacings in crystals are approximately 1 angstrom (1 × {10}^{-10} metre), ideal for producing diffraction effects in electromagnetic radiation of comparable wavelength. Friedrich and Knipping verified Laue’s predictions by photographing diffraction patterns produced by the passage of X-rays through a crystal of zinc sulfide. These experiments demonstrated that X-rays have wavelengths of about 1 angstrom and confirmed that the atoms in crystals are arranged in regular structures.

In the following year, the British physicist William Lawrence Bragg devised a particularly simple model of the scattering of X-rays from the parallel layers of atoms in a crystal. The Bragg law shows how the angles at which X-rays are most efficiently diffracted from a crystal are related to the X-ray wavelength and the distance between the layers of atoms. Bragg’s physicist father, William Henry Bragg, based his design of the first X-ray spectrometer on his son’s analysis. The pair used their X-ray spectrometer in making seminal studies of both the distribution of wavelengths in X-ray beams and the crystal structures of many common solids—an achievement for which they shared the Nobel Prize for Physics in 1915.

Particle nature

In the early 1920s, experimental studies of the scattering of X-rays from solids played a key role in establishing the particle nature of electromagnetic radiation. In 1905 German physicist Albert Einstein had proposed that electromagnetic radiation is granular, consisting of quanta (later called photons) each with an energy hf, where h is Planck’s constant (about 6.6 × {10}^{-34} joule∙second) and f is the frequency of the radiation. Einstein’s hypothesis was strongly supported in subsequent studies of the photoelectric effect and by the successes of Danish physicist Niels Bohr’s model of the hydrogen atom and its characteristic emission and absorption spectra (see Bohr atomic model). Further verification came in 1922 when American physicist Arthur Compton successfully treated the scattering of X-rays from the atoms in a solid as a set of collisions between X-ray photons and the loosely bound outer electrons of the atoms.

Adapting the relation between momentum and energy for a classical electromagnetic wave to an individual photon, Compton used conservation of energy and conservation of momentum arguments to derive an expression for the wavelength shift of scattered X-rays as a function of their scattering angle. In the so-called Compton effect, a colliding photon transfers some of its energy and momentum to an electron, which recoils. The scattered photon must thus have less energy and momentum than the incoming photon, resulting in scattered X-rays of slightly lower frequency and longer wavelength. Compton’s careful measurements of this small effect, coupled with his successful theoretical treatment (independently derived by the Dutch scientist Peter Debye), provided convincing evidence for the existence of photons. The approximate wavelength range of the X-ray portion of the electromagnetic spectrum, 10−8 to 10−12 metre, corresponds to a range of photon energies from about 100 eV (electron volts) to 1 MeV (million electron volts).

#330 Re: Dark Discussions at Cafe Infinity » crème de la crème » 2025-10-23 17:07:43

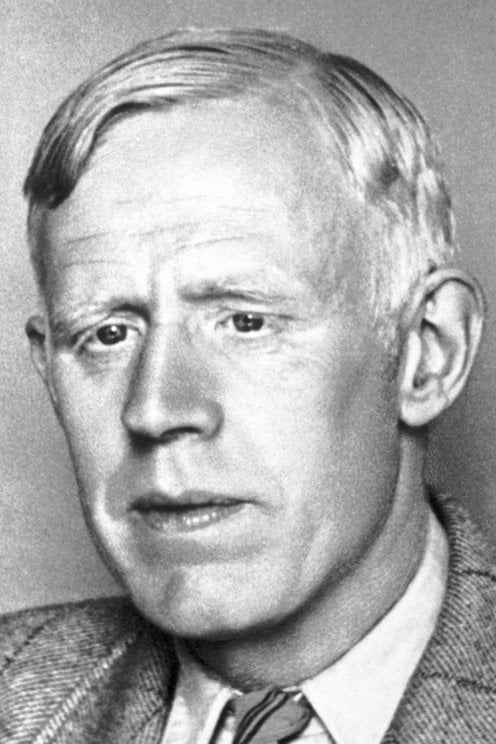

2372) Odd Hassel

Gist:

Work

In nature organisms are composed of an enormously varied number of chemical compounds, with the element carbon as a common component. The binding energy between atoms in carbon compounds determines their structure, but the structures are not completely rigid. They are flexible to a certain degree. Consequently, molecules can assume different conformations, which has ramifications for their way of reacting with other substances. At the end of the 1940s, Odd Hassel published pioneering works about different conformations for ring-shaped molecules with six carbon atoms.

Summary

Odd Hassel (born May 17, 1897, Kristiania [now Oslo], Nor.—died May 11, 1981, Oslo) was a Norwegian physical chemist and corecipient, with Derek H.R. Barton of Great Britain, of the 1969 Nobel Prize for Chemistry for his work in establishing conformational analysis (the study of the three-dimensional geometric structure of molecules).

Hassel studied at the University of Oslo and received his doctorate at the University of Berlin in 1924. He joined the faculty of the University of Oslo in 1925 and from 1934 to 1964 was a professor of physical chemistry and director of the physical chemistry department. He began intensive research on the structure of cyclohexane (a 6-carbon hydrocarbon molecule) and its derivatives in 1930 and discovered the existence of two forms of cyclohexane. At this time he set forth the basic tenets of conformational analysis and wrote Kristallchemie (1934; Crystal Chemistry). After the mid-1950s Hassel’s research dealt mainly with the structure of organic halogen compounds.

Details

Odd Hassel (17 May 1897 – 11 May 1981) was a Norwegian physical chemist and Nobel Laureate.

Biography

Hassel was born in Kristiania (now Oslo), Norway. His parents were Ernst Hassel (1848–1905), a gynaecologist, and Mathilde Klaveness (1860–1955). In 1915, he entered the University of Oslo where he studied mathematics, physics and chemistry, and graduated in 1920. Victor Goldschmidt was Hassel's tutor when he began studies in Oslo, while Heinrich Jacob Goldschmidt, Victor's father, was Hassel's thesis advisor. Father and son were important figures in Hassel's life and they remained friends. After taking a year off from studying, he went to Munich, Germany to work in the laboratory of Professor Kasimir Fajans.

His work there led to the detection of absorption indicators. After moving to Berlin, he worked at the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute, where he began to do research on X-ray crystallography.[5] He furthered his research with a Rockefeller Fellowship, obtained with the help of Fritz Haber. In 1924, he obtained his PhD from Humboldt University of Berlin, before moving to his alma mater, the University of Oslo, where he worked from 1925 through 1964. He became a professor in 1934.

His work was interrupted in October, 1943 when he and other university staff members were arrested by the Nasjonal Samling and handed over to the occupation authorities. He spent time in several detention camps, until he was released in November, 1944.

Work

Heinrich Jacob Goldschmidt was Hassel's thesis advisor and father of Victor Goldschmidt.

Hassel originally focused on inorganic chemistry, but beginning in 1930 his work concentrated on problems connected with molecular structure, particularly the structure of cyclohexane and its derivatives. He introduced the Norwegian scientific community to the concepts of the electric dipole moments and electron diffraction. The work for which he is best known established the three-dimensionality of molecular geometry. He focused his research on ring-shaped carbon molecules, which he suspected filled three dimensions instead of two, the common belief of the time. By using the number of bonds between the carbon and hydrogen atoms, Hassel demonstrated the impossibility of the molecules existing on only one plane. This discovery led to him being awarded the Nobel Prize in Chemistry for 1969.

Honors

Hassel was awarded the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 1969, shared with English chemist Derek Barton.

He received the Guldberg-Waage Medal (Guldberg-Waage Medal) from the Norwegian Chemical Society and the Gunnerus Medal from the Royal Norwegian Society of Science and Letters, both in 1964.

Hassel held honorary degrees from the University of Copenhagen (1950) and Stockholm University (1960). An annual lecture named in his honor is given at the University of Oslo.

He was an honorary Fellow of the Norwegian Chemical Society, Chemical Society of London, Norwegian Academy of Science and Letters, Royal Danish Academy of Sciences and Letters and Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences.

He was made a Knight of the Order of St. Olav in 1960.

#331 Dark Discussions at Cafe Infinity » Coach Quotes - II » 2025-10-23 16:36:27

- Jai Ganesh

- Replies: 0

Coach Quotes - II

1. I'd give my life to be the national team coach. - Diego Maradona

2. My coach is pushing me harder than ever to make sure I stay at a good level. - Usain Bolt

3. My brother Gary, who was my coach, five years my elder, studied human movements at Queensland University in Brisbane. We used to train together every day, and we'd train for so long that at the end of a session, we would physically almost collapse. - Matthew Hayden

4. I'm very fortunate to have a coach that I got to stay with all this time. Every year the bond gets stronger and better, and we understand each other more. And it's like she can tell if I walk into the gym what kind of mood I'm in, what she has to fix for the practice I need, or how I'm feeling. - Simone Biles

5. My coach keeps telling me to say I'm not going to retire. I should just go through the motions and see what I feel every year and see if I really want to do it, but personally, I want to do it, but my coach says just take your time, don't rush. - Usain Bolt

6. There are times I might coach one or two workouts a year when the regular coach gets caught in traffic. - Mark Spitz

7. I tell you, it was kind of two-fold. I fortunately had a lot of support. My coach was amazing - he told me to focus on being prepared and that is what I did. Every athlete is nervous - any athlete who tells you they're not nervous isn't telling you the truth. I was as prepared as I could be. - Carl Lewis

8. I was born in a very poor family. I used to sell tea in a railway coach as a child. My mother used to wash utensils and do lowly household work in the houses of others to earn a livelihood. I have seen poverty very closely. I have lived in poverty. As a child, my entire childhood was steeped in poverty. - Narendra Modi.

#332 Jokes » Artichoke Jokes - II » 2025-10-23 16:14:47

- Jai Ganesh

- Replies: 0

Q: What do you call a conversation between two artichokes?

A: A heart to heart.

* * *

Q: Why don't rednecks eat artichokes?

A: Because artichokes have "achy breaky hearts".

* * *

Q: How do artichokes apologize?

A: With their heart and soul.

* * *

Q: Why are artichokes brave in battle?

A: Because they have a bunch of hearts.

* * *

Knock Knock!

Who's there?

Artichokes.

Artichokes, who?

Artichokes when he eats too fast!

* * *

#333 Re: This is Cool » Miscellany » 2025-10-23 16:08:25

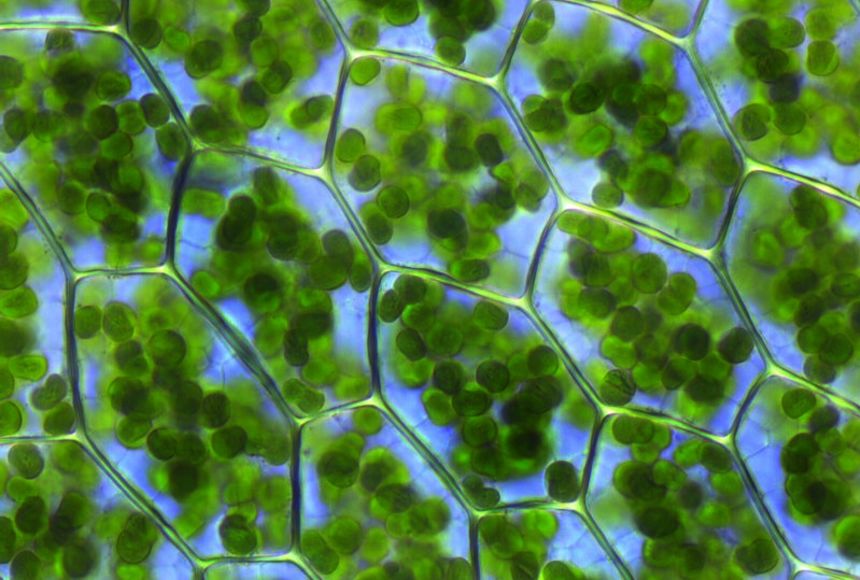

2424) Chlorophyll

Gist

Chlorophyll is the green pigment in plants, algae, and cyanobacteria that is essential for photosynthesis, the process of converting light energy into chemical energy to create food. It is concentrated in plant cells within structures called chloroplasts and gives plants their characteristic green color. Beyond its primary role in photosynthesis, it's used as a natural green colorant and has been studied for potential antioxidant and anti-aging benefits, though these require more research.

Chlorophyll is a pigment that gives plants their green color, and it helps plants create their own food through photosynthesis.

Chlorophyll is found in the thylakoid membranes of chloroplasts within the cells of photosynthetic organisms, such as green plants, algae, and cyanobacteria. It is concentrated within the grana (stacks of thylakoids) in plant cells, which are the specific sites where the light-dependent reactions of photosynthesis occur.

Summary

Chlorophyll is any of several related green pigments found in cyanobacteria and in the chloroplasts of algae and plants. Its name is derived from the Greek words (khloros, "pale green") and (phyllon, "leaf"). Chlorophyll allows plants to absorb energy from light. Those pigments are involved in oxygenic photosynthesis, as opposed to bacteriochlorophylls, related molecules found only in bacteria and involved in anoxygenic photosynthesis.

Chlorophylls absorb light most strongly in the blue portion of the electromagnetic spectrum as well as the red portion. Conversely, it is a poor absorber of green and near-green portions of the spectrum. Hence chlorophyll-containing tissues appear green because green light, diffusively reflected by structures like cell walls, is less absorbed. Two types of chlorophyll exist in the photosystems of green plants: chlorophyll a and b.

Uses:

Culinary

Synthetic chlorophyll is registered as a food additive colorant, and its E number is E140. Chefs use chlorophyll to color a variety of foods and beverages green, such as pasta and spirits. Absinthe gains its green color naturally from the chlorophyll introduced through the large variety of herbs used in its production. Chlorophyll is not soluble in water, and it is first mixed with a small quantity of vegetable oil to obtain the desired solution.

In marketing

In years 1950–1953 in particular, chlorophyll was used as a marketing tool to promote toothpaste, sanitary towels, soap and other products. This was based on claims that it was an odor blocker — a finding from research by F. Howard Westcott in the 1940s — and the commercial value of this attribute in advertising led to many companies creating brands containing the compound. However, it was soon determined that the hype surrounding chlorophyll was not warranted and the underlying research may even have been a hoax. As a result, brands rapidly discontinued its use. In the 2020s, chlorophyll again became the subject of unsubstantiated medical claims, as social media influencers promoted its use in the form of "chlorophyll water", for example

Details

Chlorophyll is any member of the most important class of pigments involved in photosynthesis, the process by which light energy is converted to chemical energy through the synthesis of organic compounds. Chlorophyll is found in virtually all photosynthetic organisms, including green plants, cyanobacteria, and algae. It absorbs energy from light; this energy is then used to convert carbon dioxide to carbohydrates.

Chlorophyll occurs in several distinct forms: chlorophylls a and b are the major types found in higher plants and green algae; chlorophylls c and d are found, often with a, in different algae; chlorophyll e is a rare type found in some golden algae; and bacterio-chlorophyll occurs in certain bacteria. In green plants chlorophyll occurs in membranous disklike units (thylakoids) in organelles called chloroplasts.

The chlorophyll molecule consists of a central magnesium atom surrounded by a nitrogen-containing structure called a porphyrin ring; attached to the ring is a long carbon–hydrogen side chain, known as a phytol chain. Variations are due to minor modifications of certain side groups. Chlorophyll is remarkably similar in structure to hemoglobin, the oxygen-carrying pigment found in the red blood cells of mammals and other vertebrates.

Additional Information

Chlorophyll is a pigment that gives plants their green color, and it helps plants create their own food through photosynthesis.

Green plants have the ability to make their own food. They do this through a process called photosynthesis, which uses a green pigment called chlorophyll. A pigment is a molecule that has a particular color and can absorb light at different wavelengths, depending on the color. There are many different types of pigments in nature, but chlorophyll is unique in its ability to enable plants to absorb the energy they need to build tissues.

Chlorophyll is located in a plant’s chloroplasts, which are tiny structures in a plant’s cells. This is where photosynthesis takes place. Phytoplankton, the microscopic floating plants that form the basis of the entire marine food web, contain chlorophyll, which is why high phytoplankton concentrations can make water look green.

Chlorophyll’s job in a plant is to absorb light—usually sunlight. The energy absorbed from light is transferred to two kinds of energy-storing molecules. Through photosynthesis, the plant uses the stored energy to convert carbon dioxide (absorbed from the air) and water into glucose, a type of sugar. Plants use glucose together with nutrients taken from the soil to make new leaves and other plant parts. The process of photosynthesis produces oxygen, which is released by the plant into the air.

Chlorophyll gives plants their green color because it does not absorb the green wavelengths of white light. That particular light wavelength is reflected from the plant, so it appears green.

Plants that use photosynthesis to make their own food are called autotrophs. Animals that eat plants or other animals are called heterotrophs. Because food webs in every type of ecosystem, from terrestrial to marine, begin with photosynthesis, chlorophyll can be considered a foundation for all life on Earth.

#334 Re: Jai Ganesh's Puzzles » General Quiz » 2025-10-23 15:38:21

Hi,

#10625. What does the term in Biology Dimorphism mean?

#10626. What does the terrm in Biology Dynein mean?

#335 Re: Jai Ganesh's Puzzles » English language puzzles » 2025-10-23 15:24:25

Hi,

#5821. What does the verb (used with object) conceal mean?

#5822. What does the verb (used with object) concede mean?

#336 Re: Jai Ganesh's Puzzles » Doc, Doc! » 2025-10-23 14:57:10

Hi,

#2504. What does the medical term Bradykinesia mean?

#337 Re: Jai Ganesh's Puzzles » 10 second questions » 2025-10-23 14:36:12

Hi,

#9773.

#338 Re: Jai Ganesh's Puzzles » Oral puzzles » 2025-10-23 14:25:13

Hi,

#6278.

#339 Re: Exercises » Compute the solution: » 2025-10-23 14:05:15

Hi,

2624.

#340 Science HQ » Seaborgium » 2025-10-22 22:45:45

- Jai Ganesh

- Replies: 0

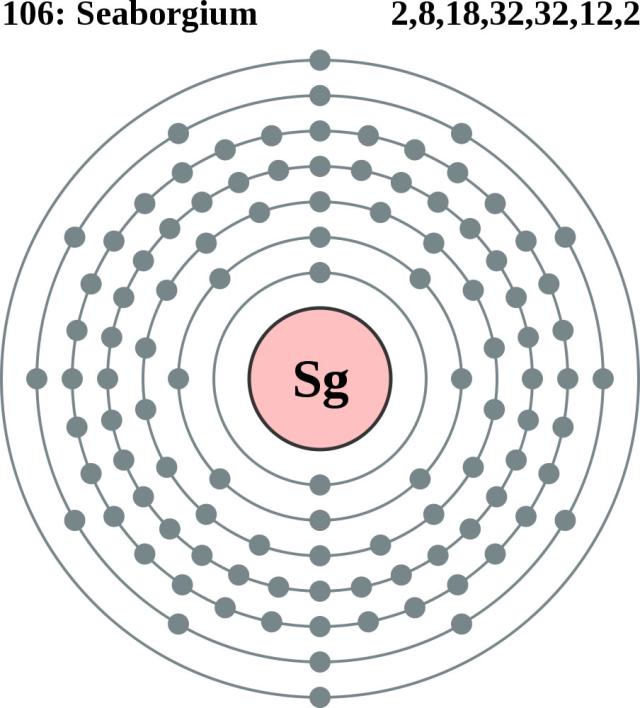

Seaborgium

Gist

Seaborgium (Sg) is a synthetic, radioactive chemical element with atomic number 106. It is a highly unstable, man-made element named after American chemist Glenn T. Seaborg. While its properties are not fully known due to its extreme instability, it is predicted to be a metal similar to tungsten, with no natural occurrence or commercial applications.

Seaborgium has no current commercial or practical applications because it is a highly radioactive synthetic element with a very short half-life. Its only use is for scientific research, primarily to study its physical and chemical properties and to help synthesize other superheavy elements.

Summary

Seaborgium is a synthetic chemical element; it has symbol Sg and atomic number 106. It is named after the American nuclear chemist Glenn T. Seaborg. As a synthetic element, it can be created in a laboratory but is not found in nature. It is also radioactive; the most stable known isotopes have half-lives on the order of several minutes.

In the periodic table of the elements, it is a d-block transactinide element. It is a member of the 7th period and belongs to the group 6 elements as the fourth member of the 6d series of transition metals. Chemistry experiments have confirmed that seaborgium behaves as the heavier homologue to tungsten in group 6. The chemical properties of seaborgium are characterized only partly, but they compare well with the chemistry of the other group 6 elements.

In 1974, a few atoms of seaborgium were produced in laboratories in the Soviet Union and in the United States. The priority of the discovery and therefore the naming of the element was disputed between Soviet and American scientists, and it was not until 1997 that the International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry (IUPAC) established seaborgium as the official name for the element. It is one of only two elements named after a living person at the time of naming, the other being oganesson, element 118.

Details

Seaborgium (Sg) is an artificially produced radioactive element in Group VIb of the periodic table, atomic number 106. In June 1974, Georgy N. Flerov of the Joint Institute for Nuclear Research at Dubna, Russia, U.S.S.R., announced that his team of investigators had synthesized and identified element 106. In September of the same year, a group of American researchers headed by Albert Ghiorso at the Lawrence Radiation Laboratory (now Lawrence Berkeley Laboratory) of the University of California at Berkeley reported their synthesis of the identical element. Disagreement arose between the two groups over the results of their experiments, both having used different procedures to achieve the synthesis. The Soviet scientists had bombarded lead-207 and lead-208 with ions of chromium-54 to produce an isotope of element 106 having a mass number of 259 and decaying with a half-life of approximately 0.007 second. The American researchers, on the other hand, had bombarded a heavy radioactive target of californium-249 with projectile beams of oxygen-18 ions, which resulted in the creation of a different isotope of element 106—one with a mass number of 263 and a half-life of 0.9 second. Russian researchers at Dubna reported their synthesis of two isotopes of the element in 1993, and a team of researchers at Lawrence Berkeley duplicated the Ghiorso group’s original experiment that same year. In honour of the American nuclear chemist Glenn T. Seaborg, American researchers tentatively named the element seaborgium, which was later ratified by the International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry. Based on its position in the periodic table, seaborgium is thought to have chemical properties akin to those of tungsten.

Additional Information:

Appearance

A radioactive metal that does not occur naturally. Only a few atoms have ever been made.

Uses

At present, it is only used in research.

Biological role

Seaborgium has no known biological role.

Natural abundance

Seaborgium is a transuranium element. It is created by bombarding californium-249 with oxygen-18 nuclei.

#341 Re: Exercises » Mathematical Induction » 2025-10-22 20:23:34

#342 Re: Dark Discussions at Cafe Infinity » crème de la crème » 2025-10-22 16:51:56

2371) Derek Barton

Gist:

Work

In nature organisms are composed of an enormously varied number of chemical compounds, with the element carbon as a common component. The binding energy between atoms in carbon compounds determines their structure, but the structures are not completely rigid. They are flexible to a certain degree. Consequently, molecules can assume different conformations, which has ramifications for their way of reacting with other substances. In the 1950s Derek Barton charted conformations for a number of substances with biological importance, such as bile acids, sex hormones, cortisone and cholesterol.

Summary

Sir Derek H.R. Barton (born September 8, 1918, Gravesend, Kent, England—died March 16, 1998, College Station, Texas, U.S.) was a joint recipient, with Odd Hassel of Norway, of the 1969 Nobel Prize for Chemistry for his work on “conformational analysis,” the study of the three-dimensional geometric structure of complex molecules, now an essential part of organic chemistry.

Education and early career

The son and grandson of successful carpenters, Barton was able to attend a good private school. Rather than join his father’s wood business after graduation, he chose to pursue higher education. After one year at Gillingham Technical College, Barton entered Imperial College of Science and Technology in London, where he developed what became a lifelong interest in the chemistry of natural products. Barton earned both his baccalaureate and doctoral degrees from Imperial College, in 1940 and 1942, respectively. Upon completing his doctoral research, Barton spent much of the remainder of World War II investigating invisible inks for military intelligence purposes. After a year working for the chemical industry in Birmingham, he joined the faculty of Imperial College in 1945, first as an assistant lecturer and later as a research fellow. Although the college did not offer him a position in organic chemistry, he was able to teach physical and inorganic chemistry there for four years while conducting research in his field of choice, organic chemistry. Spending time in all of these areas of chemistry helped him better appreciate the value of these interrelated disciplines.

Conformational analysis

In 1949 Barton took up a one-year visiting professorship at Harvard University that proved crucial to his intellectual and professional development. At that time he formed what became a lifelong friendship and collaboration with R.B. Woodward, and he began his seminal work on conformational analysis. Barton’s four-page “The Conformation of the Steroid Nucleus” (1950) immediately caught the attention of the scientific community, particularly organic chemists. The paper’s most immediate impact was seen in the way it provided a theoretical foundation for considerable experimental work in the field of steroid structure and synthesis. Barton’s work unified many of the diverse findings about the chemical and biological behaviour of steroids that had been uncovered during the first half of the 20th century, and it was for this work that Barton received the Nobel Prize in 1969. Returning to London in 1950, Barton took up a position at Birkbeck College, University of London. There he taught organic chemistry and pursued his research on the structure and synthesis of steroids. During this time he and Woodward completed their synthesis of lanosterol, a key intermediate in the biosynthesis of steroids.

After serving a brief period as a professor of chemistry at the University of Glasgow from 1955 to 1957, Barton returned to Imperial College where he remained for 20 years. At Imperial College he introduced a number of pedagogic innovations to complement his lectures, including seminars devoted to problem solving and a tutorial system. Barton, driven by the aesthetics of his work as well as by his own intellectual curiosity, highly valued doing useful things. The posing and solving of problems were special joys; particularly difficult problems and elegant, efficient solutions made the task all the more enjoyable. Barton was happiest when all these ideals coalesced into one project, as they did with his work on the synthesis of aldosterone, a steroid hormone that controls the balance of electrolytes in the body.

In 1958 Barton collaborated on aldosterone with the Schering Corporation at its Research Institute for Medicine and Chemistry in Cambridge, Massachusetts. He discovered what is now known as the Barton reaction, a photochemical process that provided an easier means of synthesizing aldosterone. The project was a tremendous success, and Barton maintained a consulting relationship with Schering for the next 40 years. Barton’s scientific work flourished, too, as he successfully expanded his research agenda in the chemistry of radicals and photochemistry. He made significant and lasting contributions in all the areas of chemistry he explored, and he was knighted in 1972.

Later career

Although Barton officially retired twice, his final two decades were quite active and productive. A year before retiring from Imperial College, he was appointed director of research at the Institute of Organic Chemistry’s National Centre for Scientific Research in Gif-sur-Yvette, France, a position he held from 1977 to 1985. Ever pursuing the useful and the elegant, Barton devoted much of his energy during these years, in both France and the United States, to the development of new synthetic methods through the use of free radicals. He later viewed this pursuit as his true mission as a chemist. After reaching the mandatory retirement age in France in 1986, he accepted a distinguished professorship at Texas A&M University, which he held until his death.

Although Barton is most often remembered for his Nobel Prize-winning work on conformational analysis, he made considerable contributions to the art and science of organic chemistry. An outgoing scientist, Barton regularly traveled, accepted many lectureships and visiting professorships, and often worked as an industrial consultant. He adamantly believed in the sharing of knowledge and the importance of exposing one’s ideas to critical review.

Details

Sir Derek Harold Richard Barton (8 September 1918 – 16 March 1998) was an English organic chemist and Nobel Prize laureate for 1969.

Education and early life

Barton was born in Gravesend, Kent, to William Thomas and Maude Henrietta Barton (née Lukes).

He attended Gravesend Grammar School (1926–29), The King's School, Rochester (1929–32), Tonbridge School (1932–35) and Medway Technical College (1937–39). In 1938 he entered Imperial College London, where he graduated in 1940 and obtained his PhD degree in Organic Chemistry in 1942.

Career and research

From 1942 to 1944, Barton was a government research chemist, then from 1944 to 1945 he worked for Albright and Wilson in Birmingham. He then became Assistant Lecturer in the Department of Chemistry of Imperial College, and from 1946 to 1949 he was ICI Research Fellow.

During 1949 and 1950, he was a visiting lecturer in natural products chemistry at Harvard University, and was then appointed reader in organic chemistry and, in 1953, professor at Birkbeck College. In 1955, he became Regius Professor of Chemistry at the University of Glasgow, and in 1957, he was appointed professor of organic chemistry at Imperial College, London. In 1950, Barton showed that organic molecules could be assigned a preferred conformation based upon results accumulated by chemical physicists, in particular by Odd Hassel. Using this new technique of conformational analysis, he later determined the geometry of many other natural product molecules.

In 1969, Barton shared the Nobel Prize in Chemistry with Odd Hassel for “contributions to the development of the concept of conformation and its application in chemistry."

In 1958, Barton was appointed Arthur D. Little Visiting Professor of Massachusetts Institute of Technology, and in 1959 Karl Folkers Visiting Professor at the Universities of Illinois and Wisconsin. The same year, he was elected a foreign honorary member of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences.

In 1949, he was the first recipient of the Corday-Morgan Medal and Prize awarded by the Royal Society of Chemistry. In 1954 he was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society and the International Academy of Science, Munich as well as, in 1956, a Fellow of the Royal Society of Edinburgh; in 1965 he was appointed member of the Council for Scientific Policy. He was knighted in 1972, becoming formally styled Sir Derek in Britain. In 1978, he became Director of the Institut de Chimie des Substances Naturelles (ICSN - Gif Sur-Yvette) in France.

In 1977, on the occasion of the centenary of the Royal Institute of Chemistry, the British Post Office honoured him, and 5 other Nobel Prize-winning British chemists, with a series of four postage stamps featuring aspects of their discoveries.

He moved to the United States in 1986 (specifically Texas) and became distinguished professor at Texas A&M University and held this position for 12 years until his death.

In 1996, Barton published a comprehensive volume of his works, entitled Reason and Imagination: Reflections on Research in Organic Chemistry.

As well as for his work on conformation, his name is remembered in a number of reactions in organic chemistry, such as the Barton reaction, the Barton decarboxylation, and the Barton-McCombie deoxygenation.

The newly built Barton Science Centre at Tonbridge School in Kent, where he was educated for 4 years, completed in 2019, is named after him.

Honours and awards

Barton was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society (FRS) in 1954. In 1966 he was elected a Member of the German Academy of Sciences Leopoldina. He was elected to the United States National Academy of Sciences in 1970 and the American Philosophical Society in 1978.

- Knight Bachelor (1972)

- Légion d'honneur (1972)

Personal life

Sir Derek married three times: Jeanne Kate Wilkins (on 20 December 1944); Christiane Cognet (died 1992) (in 1969); and Judith Von-Leuenberger Cobb (1939-2012) (in 1993). He had a son by his first marriage.

#343 Re: This is Cool » Miscellany » 2025-10-22 16:25:32

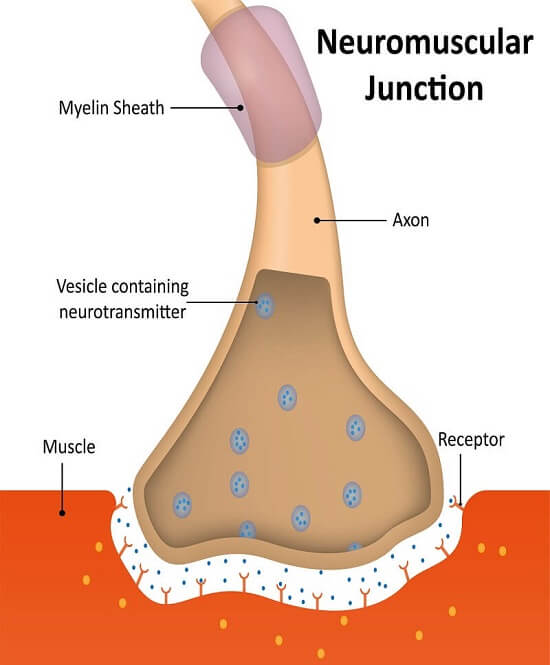

2423) Neuromuscular junction

Gist

A neuromuscular junction (NMJ) is the specialized synapse where a motor neuron transmits a signal to a skeletal muscle fiber, triggering muscle contraction. This happens when the nerve impulse reaches the neuron's end, causing it to release the neurotransmitter acetylcholine into the synaptic cleft. Acetylcholine then binds to receptors on the muscle fiber, initiating a series of events that lead to a muscle action potential and subsequent contraction.

When a nerve impulse arrives, it causes the release of the neurotransmitter acetylcholine, which binds to receptors on the muscle fiber, generating an action potential and leading to muscle movement. Disorders affecting the NMJ can lead to muscle weakness and paralysis.

Summary

A neuromuscular junction (or myoneural junction) is a chemical synapse between a motor neuron and a muscle fiber.

It allows the motor neuron to transmit a signal to the muscle fiber, causing muscle contraction.

Muscles require innervation to function—and even just to maintain muscle tone, avoiding atrophy. In the neuromuscular system, nerves from the central nervous system and the peripheral nervous system are linked and work together with muscles. Synaptic transmission at the neuromuscular junction begins when an action potential reaches the presynaptic terminal of a motor neuron, which activates voltage-gated calcium channels to allow calcium ions to enter the neuron. Calcium ions bind to sensor proteins (synaptotagmins) on synaptic vesicles, triggering vesicle fusion with the cell membrane and subsequent neurotransmitter release from the motor neuron into the synaptic cleft. In vertebrates, motor neurons release acetylcholine (ACh), a small molecule neurotransmitter, which diffuses across the synaptic cleft and binds to nicotinic acetylcholine receptors (nAChRs) on the cell membrane of the muscle fiber, also known as the sarcolemma. nAChRs are ionotropic receptors, meaning they serve as ligand-gated ion channels. The binding of ACh to the receptor can depolarize the muscle fiber, causing a cascade that eventually results in muscle contraction.

Neuromuscular junction diseases can be of genetic and autoimmune origin. Genetic disorders, such as Congenital myasthenic syndrome, can arise from mutated structural proteins that comprise the neuromuscular junction, whereas autoimmune diseases, such as myasthenia gravis, occur when antibodies are produced against nicotinic acetylcholine receptors on the sarcolemma.

Details

The body contains over 600 different skeletal muscles and each consists of thousands of muscle fibres ranging in length from a few millimetres to several centimetres. The motor nerve fibres innervating them, which arise in the spinal cord, can be more than 1 m in length. However, the area of apposition between the terminal tip of each nerve fibre and the ‘endplate’ of each muscle fibre is usually less than 50 μm (1/20 mm) in diameter. This particular type of synapse is called the neuromuscular junction (see figure). In order to generate the complex and finely controlled movements that we all take for granted, there has to be a very efficient, fail-safe, and one-way transmission between the nerve and the muscle that ensures that muscle contractions faithfully follow commands from the central nervous system. Such neuromuscular transmission depends on the release from the motor nerve terminal of the chemical acetylcholine (ACh), and its binding to a protein receiver on the surface of the muscle, called the acetylcholine receptor (AChR).

When a nerve impulse reaches the motor nerve terminal, specialized proteins forming ion-channels in its cell membrane open transiently, allowing a short-lived entry of calcium into the terminal. Stored inside the nerve terminal, and attached to special sites on the inside of the cell membrane, are small round vesicles filled with ACh. The sudden inrush of calcium causes some of the vesicle membranes to fuse with the nerve terminal membrane, and to release their contents into the synaptic cleft between the nerve and the surface of the muscle fibre.

ACh diffuses rapidly across the ultramicroscopic 50 nm gap and binds to the AChRs that are very densely packed on the tops of the synaptic folds on the muscle fibre. When two ACh molecules bind to each AChR, its central pore (channel) opens, allowing small positively charged ions, mainly sodium, to enter the muscle, resulting in a local reduction in the potential across the membrane (depolarization). The release of many ACh-containing vehicles by a nerve impulse leads to a large depolarization called the endplate potential, which in turn opens the voltage-sensitive sodium channels situated at the base of each synaptic fold. These are responsible for starting an ‘all or nothing’ action potential that is propagated along the muscle fibre in each direction and initiates muscle contraction.

After about a millisecond, the AChR pore closes and ACh unbinds and is broken down by an enzyme, ACh esterase (AChE), that sits in the synaptic cleft. Choline is then taken back into the nerve terminal by special transporters, and used to make more ACh; this is stored in newly-formed synaptic vesicles, themselves made up of recycled nerve terminal membrane. The whole sequence of events, from the inrush of calcium to the initiation of the action potential, takes place in less than two milliseconds.

Many of the earliest studies on chemical synaptic transmission began with the autonomic nervous system, but they were soon extended to skeletal muscles when Dale and his colleagues (1936) showed that stimulation of motor nerves released ACh, and that ACh can induce muscle contraction. The action of ACh could be increased by using a drug, eserine, that inhibits the ACh esterase, and the action of ACh on the muscle could be blocked by the arrow poison, curare. Katz and his co-workers subsequently used intracellular micro-electrodes to measure the endplate potentials and showed that these followed the release of many vesicles of ACh, and that a similar depolarization of the muscle occurred when ACh was applied directly onto the neuromuscular junction with a micropipette.

The neuromuscular junction, unlike most of the nervous system, is accessible to factors circulating in the blood. This can be both an advantage and a disadvantage. For many surgical operations, one of the important roles of the anesthetist is to relax the patient's muscles using an intravenous injection of the otherwise poisonous curare-like drugs — whilst taking over artificially the muscular function of breathing. Similarly, many species of venomous animals, such as snakes and scorpions, make toxins that paralyse their prey, and in some parts of the world this can also be a serious hazard for humans. Such toxins are rapidly absorbed and carried to the neuromuscular junction where they bind with extraordinary efficiency to the AChRs and other ion channel proteins, leading to muscle paralysis which can prevent breathing. Another important toxin is botulinum, which is produced by bacteria contaminating certain foods. Botulinum toxin blocks the release of ACh from the motor nerve terminals, and can cause fatal paralysis in babies; on the other hand it has recently found use as a treatment by local injection into muscles that are subject to uncontrollable severe spasm.

These neurotoxins have also provided marvellous tools for investigating function. For instance, a particular snake toxin, alpha-bungarotoxin, binds very strongly to AChRs and has been of immense use in the study of diseases that affect neuromuscular transmission. In myasthenia gravis (mys: muscle: aesthenia: weakness), the patient suffers from serious weakness and fatigue that can be life-threatening if it involves swallowing and breathing muscles. Myasthenia was first described in 1672 by the very distinguished London physician and anatomist, Thomas Willis. Over three hundred years later, Jim Patrick and Jon Lindstrom at the Salk Institute in California induced a myasthenia gravis-like disease in rabbits by injecting them with AChR protein purified from the electric organs of certain fish. The rabbits responded to the ‘foreign’ protein by making antibodies to it, but these antibodies gained access to the rabbits' neuromuscular junctions, recognized the muscle AChRs, and reduced their function, producing muscle weakness. Following these experimental observations, radioactively-labelled alpha-bungarotoxin was used to show that patients with myasthenia have reduced numbers of AChRs at their neuromuscular junctions, and subsequently that this is caused by serum antibodies that bind to AChRs — just as in the rabbits. Drugs that inhibit the ACh esterase enzyme cause clinical improvement because they prolong the action of ACh, as first demonstrated in 1934 by Mary Walker, a young doctor in London, but nowadays the most important treatment is to reduce the circulating antibodies that bind AChR.

Additional Information

Nneuromuscular junction is a site of chemical communication between a nerve fibre and a muscle cell. The neuromuscular junction is analogous to the synapse between two neurons. A nerve fibre divides into many terminal branches; each terminal ends on a region of muscle fibre called the end plate. Embedded in the end plate are thousands of receptors, which are long protein molecules that form channels through the membrane. Upon stimulation by a nerve impulse, the terminal releases the chemical neurotransmitter acetylcholine from synaptic vesicles. Acetylcholine then binds to the receptors, the channels open, and sodium ions flow into the end plate. This initiates the end-plate potential, the electrical event that leads to contraction of the muscle fibre.

#344 Dark Discussions at Cafe Infinity » Coach Quotes - I » 2025-10-22 15:41:16

- Jai Ganesh

- Replies: 0

Coach Quotes - I

1. My old drama coach used to say, 'Don't just do something, stand there.' Gary Cooper wasn't afraid to do nothing. - Clint Eastwood

2. I don't think a coach becomes the right coach until he wins a championship. - Kobe Bryant

3. I've always believed one thing. Just because you say 'good morning' and 'good night' to a coach doesn't mean you respect him. You should have respect in your heart. - Hardik Pandya

4. Everyone needs a coach. It doesn't matter whether you're a basketball player, a tennis player, a gymnast or a bridge player. - Bill Gates

5. My dad was my best friend and greatest role model. He was an amazing dad, coach, mentor, soldier, husband and friend. - Tiger Woods

6. One of the things that first attracted me to chess is that it brings you into contact with intelligent, civilized people - men of the stature of Garry Kasparov, the former world champion, who was my part-time coach. - Magnus Carlsen

7. My mum, Kathy, works as a GP and my dad, Mark, was a high school maths teacher. He now manages mum's practice and is also my cricket coach. We are a close-knit family. - Ellyse Perry

8. The civilized man has built a coach, but has lost the use of his feet. - Ralph Waldo Emerson.

#345 Jokes » Artichoke Jokes - I » 2025-10-22 15:26:14

- Jai Ganesh

- Replies: 0

Q: What did the artichoke say to the man eating a salad?

A: Have a heart.

* * *

Q: Why did the tin man from Oz eat artichokes?

A: He wanted a heart!

* * *

Q: What water yields the most beautiful artichoke garden?

A: Perspiration!

* * *

Q: What happens when you eat artichokes?

A: It breaks their hearts.

* * *

Q: Where did the artichoke go to have a few drinks?

A: The Salad Bar!

* * *

#346 Re: Jai Ganesh's Puzzles » General Quiz » 2025-10-22 15:05:24

Hi,

#10623. What does the term in Biology DNA sequencing mean?

#10624. What does the term in Biology Drug mean?

#347 Re: Jai Ganesh's Puzzles » English language puzzles » 2025-10-22 14:50:47

Hi,

#5819. What does the noun feat mean?

#5820. What does the adjective febrile mean?

#348 Re: Jai Ganesh's Puzzles » Doc, Doc! » 2025-10-22 14:30:03

Hi,

#2503. What does the medical term Fibroadenoma mean?

#349 Re: Jai Ganesh's Puzzles » 10 second questions » 2025-10-22 14:19:33

Hi,

#9772.

#350 Re: Jai Ganesh's Puzzles » Oral puzzles » 2025-10-22 13:49:37

Hi,

#6278.