Math Is Fun Forum

You are not logged in.

- Topics: Active | Unanswered

#401 Jokes » Apple Jokes - II » 2025-10-17 14:51:39

- Jai Ganesh

- Replies: 0

Q: What kind of apple isn't an apple?

A: A pineapple.

* * *

Q: What did the apple say to the apple pie?

A: "You've got some crust."

* * *

Q: What's worse than finding a worm in your apple?

A: Taking a bite and finding half a worm.

* * *

Q: If an apple a day keeps the doctor away, what does an onion do?

A: Keeps everyone away.

* * *

Q: Where do bugs go to watch the big game?

A: Apple-Bees.

* * *

#402 Re: Jai Ganesh's Puzzles » 10 second questions » 2025-10-17 14:28:21

Hi,

#9767.

#403 Re: Jai Ganesh's Puzzles » Oral puzzles » 2025-10-17 14:14:52

Hi,

#6273.

#404 Re: Exercises » Compute the solution: » 2025-10-17 13:39:59

Hi,

2617.

#405 This is Cool » Phosphoric Acid » 2025-10-16 22:32:07

- Jai Ganesh

- Replies: 0

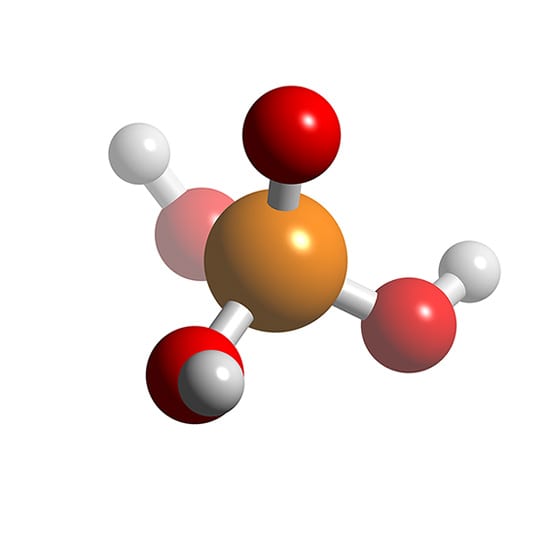

Phosphoric Acid

Gist

Phosphoric acid (H3PO4) is a weak mineral acid used in food, agriculture, and industry, and it is found as a clear liquid or white crystalline solid. In foods, it's used as an acidulant and preservative, while in fertilizers, it promotes plant growth. Due to its corrosive nature, concentrated solutions require protective gear to avoid skin, eye, and respiratory irritation.

Phosphoric acid has numerous uses, most notably in the production of phosphate fertilizers. It is also used in the food and beverage industry as an acidic flavoring agent and preservative, particularly in soft drinks. Other common applications include metal treatment, cleaning products, water treatment, detergents, and in the manufacturing of some pharmaceuticals and personal care products.

Summary

Phosphoric acid (orthophosphoric acid, monophosphoric acid or phosphoric(V) acid) is a colorless, odorless phosphorus-containing solid, and inorganic compound with the chemical formula H3PO4. It is commonly encountered as an 85% aqueous solution, which is a colourless, odourless, and non-volatile syrupy liquid. It is a major industrial chemical, being a component of many fertilizers.

The name "orthophosphoric acid" can be used to distinguish this specific acid from other "phosphoric acids", such as pyrophosphoric acid. Nevertheless, the term "phosphoric acid" often means this specific compound; and that is the current IUPAC nomenclature.

Purification

Phosphoric acid produced from phosphate rock or thermal processes often requires purification. A common purification method is liquid–liquid extraction, which involves the separation of phosphoric acid from water and other impurities using organic solvents, such as tributyl phosphate (TBP), methyl isobutyl ketone (MIBK), or n-octanol. Nanofiltration involves the use of a premodified nanofiltration membrane, which is functionalized by a deposit of a high molecular weight polycationic polymer of polyethyleneimines. Nanofiltration has been shown to significantly reduce the concentrations of various impurities, including cadmium, aluminum, iron, and rare earth elements. The laboratory and industrial pilot scale results showed that this process allows the production of food-grade phosphoric acid.

Fractional crystallization can achieve higher purities typically used for semiconductor applications. Usually a static crystallizer is used. A static crystallizer uses vertical plates, which are suspended in the molten feed and which are alternatingly cooled and heated by a heat transfer medium. The process begins with the slow cooling of the heat transfer medium below the freezing point of the stagnant melt. This cooling causes a layer of crystals to grow on the plates. Impurities are rejected from the growing crystals and are concentrated in the remaining melt. After the desired fraction has been crystallized, the remaining melt is drained from the crystallizer. The purer crystalline layer remains adhered to the plates. In a subsequent step, the plates are heated again to liquify the crystals and the purified phosphoric acid drained into the product vessel. The crystallizer is filled with feed again and the next cooling cycle is started.

Details

Phosphoric acid, (H3PO4) is the most important oxygen acid of phosphorus, used to make phosphate salts for fertilizers. It is also used in dental cements, in the preparation of albumin derivatives, and in the sugar and textile industries. It serves as an acidic, fruitlike flavouring in food products.

Pure phosphoric acid is a crystalline solid (melting point 42.35° C, or 108.2° F); in less concentrated form it is a colourless syrupy liquid. The crude acid is prepared from phosphate rock, while acid of higher purity is made from white phosphorus.

Phosphoric acid forms three classes of salts corresponding to replacement of one, two, or three hydrogen atoms. Among the important phosphate salts are: sodium dihydrogen phosphate (NaH2PO4), used for control of hydrogen ion concentration (acidity) of solutions; disodium hydrogen phosphate (Na2HPO4), used in water treatment as a precipitant for highly charged metal cations; trisodium phosphate (Na3PO4), used in soaps and detergents; calcium dihydrogen phosphate or calcium superphosphate (Ca[H2PO4]2), a major fertilizer ingredient; calcium monohydrogen phosphate (CaHPO4), used as a conditioning agent for salts and sugars.

Phosphoric acid molecules interact under suitable conditions, often at high temperatures, to form larger molecules (usually with loss of water). Thus, diphosphoric, or pyrophosphoric, acid (H4P2O7) is formed from two molecules of phosphoric acid, less one molecule of water. It is the simplest of a homologous series of long chain molecules called polyphosphoric acids, with the general formula H(HPO3)nOH, in which n = 2, 3, 4, . . . . Metaphosphoric acids, (HPO3)n, in which n = 3, 4, 5, . . ., are another class of polymeric phosphoric acids. The known metaphosphoric acids are characterized by cyclic molecular structures. The term metaphosphoric acid is used also to refer to a viscous, sticky substance that is a mixture of both long chain and ring forms of (HPO3)n. The various polymeric forms of phosphoric acid are also prepared by hydration of phosphorus oxides.

Additional Information

Phosphoric acid, also known as orthophosphoric acid, is a chemical compound. It is also an acid. Its chemical formula is H3PO4. It contains hydrogen and phosphate ions. Its official IUPAC name is trihydroxidooxidophosphorus.

Properties

Phosphoric acid is a white solid. It melts easily to make a viscous liquid. It tastes sour when diluted (mixed with a lot of water). It can be deprotonated three times. It is very strong, although not as much as the other acids like hydrochloric acid. It does not have any odor. It is corrosive when concentrated. Salts of phosphoric acid are called phosphates.

Preparation

Phosphoric acid can be made by dissolving phosphorus(V) oxide in water. This makes a very pure phosphoric acid that is good for food. A less pure form is made by reacting sulfuric acid with phosphate rock. This can be purified to make food-grade phosphoric acid if needed.

Uses

It is used to make sodas sour. It is also used when a nonreactive acid is needed. It can be used to make hydrogen halides, such as hydrogen chloride. Phosphoric acid is heated with a sodium halide to make the hydrogen halide and sodium phosphate. It is used to react with rust to make black iron(III) phosphate, which can be scraped off, leaving pure iron. It can be used to clean teeth.

There are many minor uses of phosphoric acid. Phosphoric acid with a certain isotope of phosphorus is used for nuclear magnetic resonance. It is also used as an electrolyte in some fuel cells. It can be used as a flux. It can etch certain things in semiconductor making.

Safety

Phosphoric acid is one of the least toxic acids. When it is diluted, it just has a sour taste. When it is concentrated, it can corrode metals.

#406 Re: Dark Discussions at Cafe Infinity » crème de la crème » 2025-10-16 17:29:43

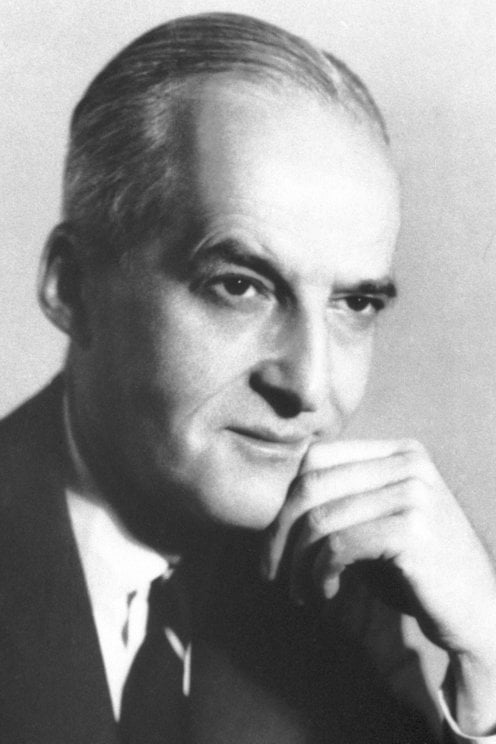

2366) Luis Federico Leloir

Gist:

Work

Carbohydrates, including sugars and starches, are of paramount importance to the life processes of organisms. Luis Leloir demonstrated that nucleotides—molecules that also constitute the building blocks of DNA molecules—are crucial when carbohydrates are generated and converted. In 1949 Leloir discovered that one type of sugar’s conversion to another depends on a molecule that consists of a nucleotide and a type of sugar. He later showed that the generation of carbohydrates is not an inversion of metabolism, as had been assumed previously, but processes with other steps.

Summary

Luis Federico Leloir (born Sept. 6, 1906, Paris, France—died Dec. 2, 1987, Buenos Aires, Arg.) was an Argentine biochemist who won the Nobel Prize for Chemistry in 1970 for his investigations of the processes by which carbohydrates are converted into energy in the body.

After serving as an assistant at the Institute of Physiology, University of Buenos Aires, from 1934 to 1935, Leloir worked a year at the biochemical laboratory at the University of Cambridge and in 1937 returned to the Institute of Physiology, where he undertook investigations of the oxidation of fatty acids. In 1947 he obtained financial support to set up the Institute for Biochemical Research, Buenos Aires, where he began research on the formation and breakdown of lactose, or milk sugar, in the body. That work ultimately led to his discovery of sugar nucleotides, which are key elements in the processes by which sugars stored in the body are converted into energy. He also investigated the formation and utilization of glycogen and discovered certain liver enzymes that are involved in its synthesis from glucose.

Details

Luis Federico Leloir (September 6, 1906 – December 2, 1987) was an Argentine physician and biochemist who received the 1970 Nobel Prize in Chemistry for his discovery of the metabolic pathways by which carbohydrates are synthesized and converted into energy in the body. Although born in France, Leloir received the majority of his education at the University of Buenos Aires and was director of the private research group Fundación Instituto Campomar until his death in 1987. His research into sugar nucleotides, carbohydrate metabolism, and renal hypertension garnered international attention and led to significant progress in understanding, diagnosing and treating the congenital disease galactosemia. Leloir is buried in La Recoleta Cemetery, Buenos Aires.

Biography:

Early years

Leloir's parents, Federico Augusto Rufino and Hortencia Aguirre de Leloir, traveled from Buenos Aires to Paris in the middle of 1906 with the intention of treating Federico's illness. However, Federico died in late August, and a week later Luis was born in an old house at 81 Víctor Hugo Road in Paris, a few blocks away from the Arc de Triomphe. After returning to Argentina in 1908, Leloir lived together with his eight siblings on their family's extensive property El Tuyú that his grandparents had purchased after their immigration from the Basque Country of northern Spain: El Tuyú comprises 400 {km}^{2} of sandy land along the coastline from San Clemente del Tuyú to Mar de Ajó which has since become a popular tourist attraction.

During his childhood, the future Nobel Prize winner found himself observing natural phenomena with particular interest; his schoolwork and readings highlighted the connections between the natural sciences and biology. His education was divided between Escuela General San Martín (primary school), Colegio Lacordaire (secondary school), and for a few months at Beaumont College in England. His grades were unspectacular, and his first stint in college ended quickly when he abandoned his architectural studies that he had begun in Paris' École Polytechnique.

It was during the 1920s that Leloir invented salsa golf (golf sauce). After being served prawns with the usual sauce during lunch with a group of friends at the Ocean Club in Mar del Plata, Leloir came up with a peculiar combination of ketchup and mayonnaise to spice up his meal. With the financial difficulties that later plagued Leloir's laboratories and research, he would joke, "If I had patented that sauce, we'd have a lot more money for research right now.

Nobel Prize

On December 2, 1970, Leloir received the Nobel Prize for Chemistry from the King of Sweden for his discovery of the metabolic pathways in lactose, becoming only the third Argentine to receive the prestigious honor in any field at the time. In his acceptance speech at Stockholm, he borrowed from Winston Churchill's famous 1940 speech to the House of Commons and remarked, "never have I received so much for so little". Leloir and his team reportedly celebrated by drinking champagne from test tubes, a rare departure from the humility and frugality that characterized the atmosphere of Fundación Instituto Campomar under Leloir's direction. The $80,000 prize money was spent directly on research, and when asked about the significance of his achievement, Leloir responded:

"This is only one step in a much larger project. I discovered (no, not me: my team) the function of sugar nucleotides in cell metabolism. I want others to understand this, but it is not easy to explain: this is not a very noteworthy deed, and we hardly know even a little."

#407 Re: This is Cool » Miscellany » 2025-10-16 16:56:15

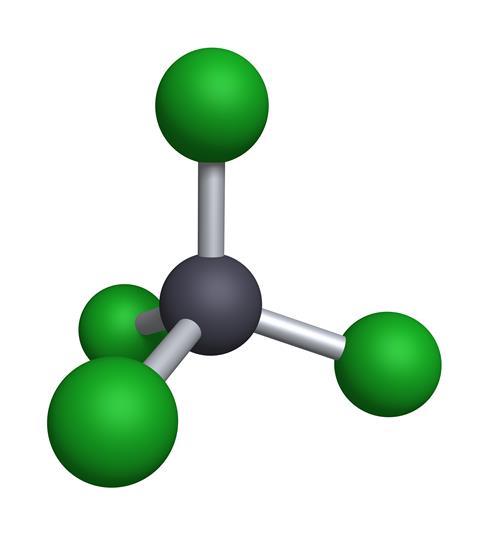

2419) Carbon Tetrachloride

Gist

Carbon tetrachloride (CCl4) is a synthetic, non-flammable, colorless liquid with a sweet odor. It was historically used in cleaning products, fire extinguishers, and as a precursor for refrigerants, but its use has been significantly reduced due to its high toxicity. It is harmful to the liver, kidneys, and central nervous system, is considered a suspected human carcinogen, and also depletes the ozone layer.

Carbon tetrachloride (CCl4) has historically been used as a solvent, a cleaning agent, and in fire extinguishers, but its use has been largely phased out due to severe health and environmental concerns. Its primary modern use is as a feedstock for producing other chemicals, such as refrigerants, and it has a few niche industrial and laboratory applications.

Summary

Carbon tetrachloride, also known by many other names (such as carbon tet for short and tetrachloromethane, also recognised by the IUPAC), is a chemical compound with the chemical formula CCl4. It is a non-flammable, dense, colourless liquid with a chloroform-like sweet odour that can be detected at low levels. It was formerly widely used in fire extinguishers, as a precursor to refrigerants, an anthelmintic and a cleaning agent, but has since been phased out because of environmental and safety concerns. Exposure to high concentrations of carbon tetrachloride can affect the central nervous system and degenerate the liver and kidneys. Prolonged exposure can be fatal.

Properties

In the carbon tetrachloride molecule, four chlorine atoms are positioned symmetrically as corners in a tetrahedral configuration joined to a central carbon atom by single covalent bonds. Because of this symmetric geometry, CCl4 is non-polar. Methane gas has the same structure, making carbon tetrachloride a halomethane. As a solvent, it is well suited to dissolving other non-polar compounds such as fats and oils. It can also dissolve iodine. It is volatile, giving off vapors with an odor characteristic of other chlorinated solvents, somewhat similar to the tetrachloroethylene odor reminiscent of dry cleaners' shops.

With a specific gravity greater than 1, carbon tetrachloride will be present as a dense nonaqueous phase liquid if sufficient quantities are spilt in the environment.

Details

Carbon tetrachloride is a manufactured chemical that does not occur naturally. It is a clear liquid with a sweet smell that can be detected at low levels. It is also called carbon chloride, methane tetrachloride, perchloromethane, tetrachloroethane, or benziform. Carbon tetrachloride is most often found in the air as a colorless gas. It is not flammable and does not dissolve in water very easily. It was used in the production of refrigeration fluid and propellants for aerosol cans, as a pesticide, as a cleaning fluid and degreasing agent, in fire extinguishers, and in spot removers. Because of its harmful effects, these uses are now banned and it is only used in some industrial applications.

Carbon tetrachloride appears as a clear colorless liquid with a characteristic odor. Denser than water (13.2 lb / gal) and insoluble in water. Noncombustible. May cause illness by inhalation, skin absorption and/or ingestion. Used as a solvent, in the manufacture of other chemicals, as an agricultural fumigant, and for many other uses.

Carbon tetrachloride may be found in both ambient outdoor and indoor air. The primary effects of carbon tetrachloride in humans are on the liver, kidneys, and central nervous system (CNS). Human symptoms of acute (short-term) inhalation and oral exposures to carbon tetrachloride include headache, weakness, lethargy, nausea, and vomiting. Acute exposures to higher levels and chronic (long-term) inhalation or oral exposure to carbon tetrachloride produces liver and kidney damage in humans. Human data on the carcinogenic effects of carbon tetrachloride are limited. Studies in animals have shown that ingestion of carbon tetrachloride increases the risk of liver cancer. EPA has classified carbon tetrachloride as a Group B2, probable human carcinogen.

Additional Information

Carbon tetrachloride is a colourless, dense, highly toxic, volatile, nonflammable liquid possessing a characteristic odour and belonging to the family of organic halogen compounds, used principally in the manufacture of dichlorodifluoromethane (a refrigerant and propellant).

First prepared in 1839 by the reaction of chloroform with chlorine, carbon tetrachloride is manufactured by the reaction of chlorine with carbon disulfide or with methane. The process with methane became dominant in the United States in the 1950s, but the process with carbon disulfide remains important in countries where natural gas (the principal source of methane) is not plentiful. Carbon tetrachloride boils at 77° C (171° F) and freezes at -23° C (-9° F); it is much denser than water, in which it is practically insoluble.

Formerly used as a dry-cleaning solvent, carbon tetrachloride has been almost entirely displaced from this application by tetrachloroethylene, which is much more stable and less toxic.

#408 Dark Discussions at Cafe Infinity » Club Quotes - IV » 2025-10-16 16:31:39

- Jai Ganesh

- Replies: 0

Club Quotes - IV

1. My main idea was to create a sports facility for the basics. This is why I established the club. - Sergei Bubka

2. Today I have 35 people who work in the club and associated businesses. - Sergei Bubka

3. We started with that, basically to help kids, and then we created a pole vault school, which is part of the club and exists to this day. The club and school exist. - Sergei Bubka

4. When I was 4 my mother got divorced and we were very close to each other. I always wanted to be with her. She took me everywhere. When she went for dinner with friends or when they had meetings at the tennis club, I was always there. - Martina Hingis

5. I don't belong to any clubs, and I dislike club mentality of any kind, even feminism - although I do relate to the purpose and point of feminism. More in the work of older feminists, really, like Germaine Greer. - Jane Campion

6. I grew up a little girl in the Soviet Union playing at a small sports club. Tennis gave me my life. - Anna Kournikova

7. I have been running maths clubs for children completely free. In my building in Bangalore, I conduct maths clubs for several months, and every child who attended the club was poor in mathematics and is now showing brilliant results. - Shakuntala Devi

8. I've played under some of the biggest and best managers and achieved almost everything in football. Of course it hurts when people question it, but I've come to the end of my career and can look back and say I've achieved everything with every club that I've played for. - David Beckham.

#409 Science HQ » Lawrencium » 2025-10-16 16:01:50

- Jai Ganesh

- Replies: 0

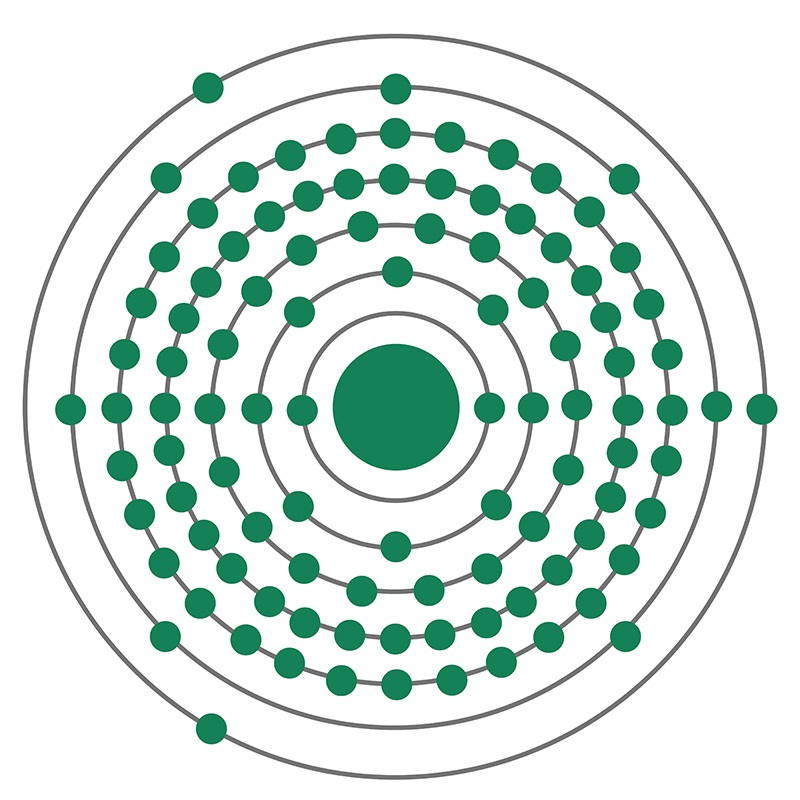

Lawrencium

Gist

Lawrencium (Lr) is a synthetic, radioactive element with atomic number 103, belonging to the actinide series. It is a highly reactive metal that does not occur naturally and is only produced in tiny quantities for scientific research. Due to its instability, it has a short half-life, though the longest-lived isotope, \(Lr\)-262, has a half-life of about 3.6 hours. It was named after Ernest Lawrence, the inventor of the cyclotron.

Lawrencium has no large-scale commercial or industrial uses because it is a synthetic, highly radioactive element produced in only tiny quantities. Its primary and sole use is for scientific research, where it helps scientists study superheavy elements, nuclear reactions, and electron configurations in laboratory settings.

Summary

Lawrencium is a synthetic chemical element; it has symbol Lr (formerly Lw) and atomic number 103. It is named after Ernest Lawrence, inventor of the cyclotron, a device that was used to discover many artificial radioactive elements. A radioactive metal, lawrencium is the eleventh transuranium element, the third transfermium, and the last member of the actinide series. Like all elements with atomic number over 100, lawrencium can only be produced in particle accelerators by bombarding lighter elements with charged particles. Fourteen isotopes of lawrencium are currently known; the most stable is 266Lr with half-life 11 hours, but the shorter-lived 260Lr (half-life 2.7 minutes) is most commonly used in chemistry because it can be produced on a larger scale.

Chemistry experiments confirm that lawrencium behaves as a heavier homolog to lutetium in the periodic table, and is a trivalent element. It thus could also be classified as the first of the 7th-period transition metals. Its electron configuration is anomalous for its position in the periodic table, having an s2p configuration instead of the s2d configuration of its homolog lutetium. However, this does not appear to affect lawrencium's chemistry.

In the 1950s, 1960s, and 1970s, many claims of the synthesis of element 103 of varying quality were made from laboratories in the Soviet Union and the United States. The priority of the discovery and therefore the name of the element was disputed between Soviet and American scientists. The International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry (IUPAC) initially established lawrencium as the official name for the element and gave the American team credit for the discovery; this was reevaluated in 1992, giving both teams shared credit for the discovery but not changing the element's name.

Details

Lawrencium (Lr) is a synthetic chemical element, the 14th member of the actinoid series of the periodic table, atomic number 103. Not occurring in nature, lawrencium (probably as the isotope lawrencium-257) was first produced (1961) by chemists Albert Ghiorso, T. Sikkeland, A.E. Larsh, and R.M. Latimer at the University of California, Berkeley, by bombarding a mixture of the longest-lived isotopes of californium (atomic number 98) with boron ions (atomic number 5) accelerated in a heavy-ion linear accelerator. The element was named after American physicist Ernest O. Lawrence. A team of Soviet scientists at the Joint Institute for Nuclear Research in Dubna discovered (1965) lawrencium-256 (26-second half-life), which the Berkeley group later used in a study with approximately 1,500 atoms to show that lawrencium behaves more like the tripositive elements in the actinoid series than like predominantly dipositive nobelium (atomic number 102). The longest-lasting isotope, lawrencium-262, has a half-life of about 3.6 hours.

Element Properties

atomic number : 103

stablest isotope : 262

oxidation state : +3.

Additional Information

The element is named after Ernest Lawrence, who invented the cyclotron particle accelerator. This was designed to accelerate sub-atomic particles around a circle until they have enough energy to smash into an atom and create a new atom. This image is based on the abstract particle trails produced in a cyclotron.

Appearance

A radioactive metal of which only a few atoms have ever been created.

Uses

Lawrencium has no uses outside research.

Biological role

Lawrencium has no known biological role.

Natural abundance

Lawrencium does not occur naturally. It is produced by bombarding californium with boron.

#410 Re: Jai Ganesh's Puzzles » General Quiz » 2025-10-16 15:22:28

Hi,

#10613. What does the term in Biology Desmosome mean?

#10614. What does the term in Biology Developmental biology mean?

#411 Re: Jai Ganesh's Puzzles » English language puzzles » 2025-10-16 14:54:02

Hi,

#5809. What does the noun hoard mean?

#5810. What does the noun hoax mean?

#412 Re: Jai Ganesh's Puzzles » Doc, Doc! » 2025-10-16 14:41:07

Hi,

#2497. What does the medical term Ophthalmoscopy mean?

#413 Re: Jai Ganesh's Puzzles » 10 second questions » 2025-10-16 14:29:07

Hi,

#9766.

#414 Re: Jai Ganesh's Puzzles » Oral puzzles » 2025-10-16 14:06:59

Hi,

#6272.

#415 Jokes » Apple Jokes - I » 2025-10-16 13:51:08

- Jai Ganesh

- Replies: 0

Q: What do you get if you cross an apple with a shellfish?

A: A crab apple !

* * *

Q: Why did Eve want to leave the garden of Eden and move to New York ?

A: She fell for the Big Apple !

* * *

Q: What type of a computer does a horse like to eat?

A Macintosh.

* * *

Q: Why did the farmer hang raincoats all over his orchard?

A: Someone told him he should get an apple Mac.

* * *

Q: How do you make an apple turnover?

A: Push it down hill.

* * *

#416 Re: Exercises » Compute the solution: » 2025-10-16 13:43:38

Hi,

2616.

#417 This is Cool » Ammonia » 2025-10-15 19:14:17

- Jai Ganesh

- Replies: 0

Ammonia

Gist

Ammonia (NH3 is a colorless, pungent gas composed of nitrogen and hydrogen, commonly used in household cleaners and fertilizers. It is a natural byproduct in the human body from protein breakdown but can be toxic at high concentrations. Ammonia's properties include being highly soluble in water, having a strong odor, and being highly alkaline.

Ammonia is used primarily in agriculture to make fertilizers, and also for industrial purposes like producing plastics, dyes, explosives, and synthetic fibers. It is also found in household products like glass and surface cleaners, and used in applications such as refrigeration and as a fuel for some rockets.

Summary

Ammonia is an inorganic chemical compound of nitrogen and hydrogen with the formula NH3. A stable binary hydride and the simplest pnictogen hydride, ammonia is a colourless gas with a distinctive pungent smell. It is widely used in fertilizers, refrigerants, explosives, cleaning agents, and is a precursor for numerous chemicals. Biologically, it is a common nitrogenous waste, and it contributes significantly to the nutritional needs of terrestrial organisms by serving as a precursor to fertilisers. Around 70% of ammonia produced industrially is used to make fertilisers in various forms and composition, such as urea and diammonium phosphate. Ammonia in pure form is also applied directly into the soil.

Ammonia, either directly or indirectly, is also a building block for the synthesis of many chemicals. In many countries, it is classified as an extremely hazardous substance. Ammonia is toxic, causing damage to cells and tissues. For this reason it is excreted by most animals in the urine, in the form of dissolved urea.

Ammonia is produced biologically in a process called nitrogen fixation, but even more is generated industrially by the Haber process. The process helped revolutionize agriculture by providing cheap fertilizers. The global industrial production of ammonia in 2021 was 235 million tonnes. Industrial ammonia is transported by road in tankers, by rail in tank wagons, by sea in gas carriers, or in cylinders. Ammonia occurs in nature and has been detected in the interstellar medium.

Ammonia boils at −33.34 °C (−28.012 °F) at a pressure of one atmosphere, but the liquid can often be handled in the laboratory without external cooling. Household ammonia or ammonium hydroxide is a solution of ammonia in water.

Details

Ammonia (NH3) is a colourless, pungent gas composed of nitrogen and hydrogen. It is the simplest stable compound of these elements and serves as a starting material for the production of many commercially important nitrogen compounds.

Uses of ammonia

The major use of ammonia is as a fertilizer. In the United States, it is usually applied directly to the soil from tanks containing the liquefied gas. The ammonia can also be in the form of ammonium salts, such as ammonium nitrate, NH4NO3, ammonium sulfate, (NH4)2SO4, and various ammonium phosphates. Urea, (H2N)2C=O, is the most commonly used source of nitrogen for fertilizer worldwide. Ammonia is also used in the manufacture of commercial explosives (e.g., trinitrotoluene [TNT], nitroglycerin, and nitrocellulose).

In the textile industry, ammonia is used in the manufacture of synthetic fibres, such as nylon and rayon. In addition, it is employed in the dyeing and scouring of cotton, wool, and silk. Ammonia serves as a catalyst in the production of some synthetic resins. More important, it neutralizes acidic by-products of petroleum refining, and in the rubber industry it prevents the coagulation of raw latex during transportation from plantation to factory. Ammonia also finds application in both the ammonia-soda process (also called the Solvay process), a widely used method for producing soda ash, and the Ostwald process, a method for converting ammonia into nitric acid.

Ammonia is used in various metallurgical processes, including the nitriding of alloy sheets to harden their surfaces. Because ammonia can be decomposed easily to yield hydrogen, it is a convenient portable source of atomic hydrogen for welding. In addition, ammonia can absorb substantial amounts of heat from its surroundings (i.e., one gram of ammonia absorbs 327 calories of heat), which makes it useful as a coolant in refrigeration and air-conditioning equipment. Finally, among its minor uses is inclusion in certain household cleansing agents.

Preparation of ammonia

Pure ammonia was first prepared by English physical scientist Joseph Priestley in 1774, and its exact composition was determined by French chemist Claude-Louis Berthollet in 1785. Ammonia is consistently among the top five chemicals produced in the United States. The chief commercial method of producing ammonia is by the Haber-Bosch process, which involves the direct reaction of elemental hydrogen and elemental nitrogen.

N2 + 3H2 → 2NH3

This reaction requires the use of a catalyst, high pressure (100–1,000 atmospheres), and elevated temperature (400–550 °C [750–1020 °F]). Actually, the equilibrium between the elements and ammonia favours the formation of ammonia at low temperature, but high temperature is required to achieve a satisfactory rate of ammonia formation. Several different catalysts can be used. Normally the catalyst is iron containing iron oxide. However, both magnesium oxide on aluminum oxide that has been activated by alkali metal oxides and ruthenium on carbon have been employed as catalysts. In the laboratory, ammonia is best synthesized by the hydrolysis of a metal nitride.

Mg3N2 + 6H2O → 2NH3 + 3Mg(OH)2

Physical properties of ammonia

Ammonia is a colourless gas with a sharp, penetrating odour. Its boiling point is −33.35 °C (−28.03 °F), and its freezing point is −77.7 °C (−107.8 °F). It has a high heat of vaporization (23.3 kilojoules per mole at its boiling point) and can be handled as a liquid in thermally insulated containers in the laboratory. (The heat of vaporization of a substance is the number of kilojoules needed to vaporize one mole of the substance with no change in temperature.) The ammonia molecule has a trigonal pyramidal shape with the three hydrogen atoms and an unshared pair of electrons attached to the nitrogen atom. It is a polar molecule and is highly associated because of strong intermolecular hydrogen bonding. The dielectric constant of ammonia (22 at −34 °C [−29 °F]) is lower than that of water (81 at 25 °C [77 °F]), so it is a better solvent for organic materials. However, it is still high enough to allow ammonia to act as a moderately good ionizing solvent. Ammonia also self-ionizes, although less so than does water.

Additional Information

Ammonia is a colorless, poisonous gas with a familiar noxious odor. It occurs in nature, primarily produced by anaerobic decay of plant and animal matter; and it also has been detected in outer space. Some plants, mainly legumes, in combination with rhizobia bacteria, “fix” atmospheric nitrogen to produce ammonia.

Ammonia has been known by its odor since ancient times. It was isolated in the 18th century by notable chemists Joseph Black (Scotland), Peter Woulfe (Ireland), Carl Wilhelm Scheele (Sweden/Germany), and Joseph Priestley (England). In 1785, French chemist Claude Louis Berthollet determined its elemental composition.

Ammonia is produced commercially via the catalytic reaction of nitrogen and hydrogen at high temperature and pressure. The process was developed in 1909 by German chemists Fritz Haber and Carl Bosch. Both received the Nobel Prize in Chemistry for their work, but in widely separated years: Haber in 1918 and Bosch in 1931. The fundamental Haber–Bosch process is still in use today.

In 2020, the worldwide ammonia production capacity was 224 million tonnes (Mt). Actual production was 187 Mt. It ranks ninth among chemicals produced globally.

Most ammonia production—≈85%—is used directly or indirectly in agriculture. Chemical fertilizers made from ammonia include urea, ammonium phosphate, ammonium nitrate, and other nitrates. Other important chemicals produced from ammonia include nitric acid, hydrazine, cyanides, and amino acids.

Ammonia was once used widely as a refrigerant. It has largely been displaced by chlorofluorocarbons and hydrochlorofluorocarbons, which are also under environmental scrutiny. Probably the most familiar household use of ammonia is in glass cleaners.

Ammonia is highly soluble in water; its exact solubility depends on temperature. Aqueous ammonia is also called ammonium hydroxide, but that molecule cannot be isolated. When ammonia is used as a ligand in coordination complexes, it is called “ammine”.

Currently ammonia is made from fossil fuel–derived hydrogen and is therefore not a “green” product, despite its widespread use in agriculture. But environmentally green ammonia may be on the horizon if the hydrogen is made by other means, such as wind- or solar-powered electrolysis of water.

Ammonia can be burned as a fuel in standard engines. A study by the catalyst company Haldor Topsoe (Kongens Lyngby, Denmark) concluded that replacing conventional ship fuels with green ammonia would be cost-efficient and would eliminate a significant source of greenhouse gases. It potentially can be used in aircraft fuels as well. During a transition period, ammonia could be mixed with conventional fuels.

#418 Re: Dark Discussions at Cafe Infinity » crème de la crème » 2025-10-15 18:13:16

2365) Louis Néel

Gist:

Work

Magnetism takes different forms, some stemming from the magnetic moments of atoms of different materials. In ferromagnetic material the magnetic moments are oriented in the same direction. In 1932 Louis Néel described the antiferromagnetism phenomenon, where nearby magnetic moments in a material are oriented in opposite directions. In 1947 he also described the ferrimagnetism phenomenon, where the magnetic moments are aligned in opposite directions but of different magnitudes. The findings became an important factor in the development of computer memory and other applications.

Summary

Louis-Eugène-Félix Néel (born November 22, 1904, Lyon, France—died November 17, 2000, Brive-Corrèze) was a French physicist who was corecipient, with the Swedish astrophysicist Hannes Alfvén, of the Nobel Prize for Physics in 1970 for his pioneering studies of the magnetic properties of solids. His contributions to solid-state physics have found numerous useful applications, particularly in the development of improved computer memory units.

Néel attended the École Normale Supérieure in Paris and the University of Strasbourg (Ph.D., 1932), where he studied under Pierre-Ernest Weiss and first began researching magnetism. He was a professor at the universities of Strasbourg (1937–45) and Grenoble (1945–76), and in 1956 he founded the Center for Nuclear Studies in Grenoble, serving as its director until 1971. Néel also was director (1971–76) of the Polytechnic Institute in Grenoble.

During the early 1930s Néel studied, on the molecular level, forms of magnetism that differ from ferromagnetism. In ferromagnetism, the most common variety of magnetism, the electrons line up (or spin) in the same direction at low temperatures. He discovered that, in some substances, alternating groups of atoms align their electrons in opposite directions (much as when two identical magnets are placed together with opposite poles aligned), thus neutralizing the net magnetic effect. This magnetic property is called antiferromagnetism. Néel’s studies of fine-grain ferromagnetics provided an explanation for the unusual magnetic memory of certain mineral deposits that has provided information on changes in the direction and strength of the Earth’s magnetic field.

Néel wrote more than 200 works on various aspects of magnetism. Mainly because of his contributions, ferromagnetic materials can be manufactured to almost any specifications for technical applications, and a flood of new synthetic ferrite materials has revolutionized microwave electronics.

Details

Louis Eugène Félix Néel (22 November 1904 – 17 November 2000) was a French physicist born in Lyon who received the Nobel Prize for Physics in 1970 for his studies of the magnetic properties of solids.

Biography

Néel studied at the Lycée du Parc in Lyon and was accepted at the École Normale Supérieure in Paris. He obtained the degree of Doctor of Science at the University of Strasbourg. He was corecipient (with the Swedish astrophysicist Hannes Alfvén) of the Nobel Prize for Physics in 1970 for his pioneering studies of the magnetic properties of solids. His contributions to solid state physics have found numerous useful applications, particularly in the development of improved computer memory units. About 1930 he suggested that a new form of magnetic behavior might exist; called antiferromagnetism, as opposed to ferromagnetism. Above a certain temperature (the Néel temperature) this behaviour stops. Néel pointed out (1948) that materials could also exist showing ferrimagnetism. Néel has also given an explanation of the weak magnetism of certain rocks, making possible the study of the history of Earth's magnetic field.

He is the instigator of the Polygone Scientifique in Grenoble.

The Louis Néel Medal, awarded annually by the European Geophysical Society, is named in Néel's honour.

Néel died at Brive-la-Gaillarde on 17 November 2000 at the age 95, just 5 days short of his 96th birthday.

#419 Re: This is Cool » Miscellany » 2025-10-15 17:54:57

2418) Protein

Gist

Protein is a complex molecule made of amino acids that performs vital functions in the body, such as building and repairing tissues, and acting as enzymes and hormones. It is essential for the structure, function, and regulation of the body's tissues and organs. The sequence of amino acids determines a protein's unique three-dimensional shape and specific function.

Protein is important because it serves as the building blocks for your body's cells, helping to build and repair tissues like muscle, bone, and skin. It is essential for numerous bodily functions, including making enzymes and hormones, supporting your immune system, and transporting nutrients.

Summary

Proteins are large biomolecules and macromolecules that comprise one or more long chains of amino acid residues. Proteins perform a vast array of functions within organisms, including catalysing metabolic reactions, DNA replication, responding to stimuli, providing structure to cells and organisms, and transporting molecules from one location to another. Proteins differ from one another primarily in their sequence of amino acids, which is dictated by the nucleotide sequence of their genes, and which usually results in protein folding into a specific 3D structure that determines its activity.

A linear chain of amino acid residues is called a polypeptide. A protein contains at least one long polypeptide. Short polypeptides, containing less than 20–30 residues, are rarely considered to be proteins and are commonly called peptides. The individual amino acid residues are bonded together by peptide bonds and adjacent amino acid residues. The sequence of amino acid residues in a protein is defined by the sequence of a gene, which is encoded in the genetic code. In general, the genetic code specifies 20 standard amino acids; but in certain organisms the genetic code can include selenocysteine and—in certain archaea—pyrrolysine. Shortly after or even during synthesis, the residues in a protein are often chemically modified by post-translational modification, which alters the physical and chemical properties, folding, stability, activity, and ultimately, the function of the proteins. Some proteins have non-peptide groups attached, which can be called prosthetic groups or cofactors. Proteins can work together to achieve a particular function, and they often associate to form stable protein complexes.

Once formed, proteins only exist for a certain period and are then degraded and recycled by the cell's machinery through the process of protein turnover. A protein's lifespan is measured in terms of its half-life and covers a wide range. They can exist for minutes or years with an average lifespan of 1–2 days in mammalian cells. Abnormal or misfolded proteins are degraded more rapidly either due to being targeted for destruction or due to being unstable.

Like other biological macromolecules such as polysaccharides and nucleic acids, proteins are essential parts of organisms and participate in virtually every process within cells. Many proteins are enzymes that catalyse biochemical reactions and are vital to metabolism. Some proteins have structural or mechanical functions, such as actin and myosin in muscle, and the cytoskeleton's scaffolding proteins that maintain cell shape. Other proteins are important in cell signaling, immune responses, cell adhesion, and the cell cycle. In animals, proteins are needed in the diet to provide the essential amino acids that cannot be synthesized. Digestion breaks the proteins down for metabolic use.

Details

Protein is a highly complex substance that is present in all living organisms. Proteins are of great nutritional value and are directly involved in the chemical processes essential for life. The importance of proteins was recognized by chemists in the early 19th century, including Swedish chemist Jöns Jacob Berzelius, who in 1838 coined the term protein, a word derived from the Greek prōteios, meaning “holding first place.” Proteins are species-specific; that is, the proteins of one species differ from those of another species. They are also organ-specific; for instance, within a single organism, muscle proteins differ from those of the brain and liver.

A protein molecule is very large compared with molecules of sugar or salt and consists of many amino acids joined together to form long chains, much as beads are arranged on a string. There are about 20 different amino acids that occur naturally in proteins. Proteins of similar function have similar amino acid composition and sequence. Although it is not yet possible to explain all of the functions of a protein from its amino acid sequence, established correlations between structure and function can be attributed to the properties of the amino acids that compose proteins.

Plants can synthesize all of the amino acids; animals cannot, even though all of them are essential for life. Plants can grow in a medium containing inorganic nutrients that provide nitrogen, potassium, and other substances essential for growth. They utilize the carbon dioxide in the air during the process of photosynthesis to form organic compounds such as carbohydrates. Animals, however, must obtain organic nutrients from outside sources. Because the protein content of most plants is low, very large amounts of plant material are required by animals, such as ruminants (e.g., cows), that eat only plant material to meet their amino acid requirements. Nonruminant animals, including humans, obtain proteins principally from animals and their products—e.g., meat, milk, and eggs. The seeds of legumes are increasingly being used to prepare inexpensive protein-rich food.

The protein content of animal organs is usually much higher than that of the blood plasma. Muscles, for example, contain about 30 percent protein, the liver 20 to 30 percent, and red blood cells 30 percent. Higher percentages of protein are found in hair, bones, and other organs and tissues with a low water content. The quantity of free amino acids and peptides in animals is much smaller than the amount of protein; protein molecules are produced in cells by the stepwise alignment of amino acids and are released into the body fluids only after synthesis is complete.

The high protein content of some organs does not mean that the importance of proteins is related to their amount in an organism or tissue; on the contrary, some of the most important proteins, such as enzymes and hormones, occur in extremely small amounts. The importance of proteins is related principally to their function. All enzymes identified thus far are proteins. Enzymes, which are the catalysts of all metabolic reactions, enable an organism to build up the chemical substances necessary for life—proteins, nucleic acids, carbohydrates, and lipids—to convert them into other substances, and to degrade them. Life without enzymes is not possible. There are several protein hormones with important regulatory functions. In all vertebrates, the respiratory protein hemoglobin acts as oxygen carrier in the blood, transporting oxygen from the lung to body organs and tissues. A large group of structural proteins maintains and protects the structure of the animal body.

Additional Information

Protein is found throughout the body—in muscle, bone, skin, hair, and virtually every other body part or tissue. It makes up the enzymes that power many chemical reactions and the hemoglobin that carries oxygen in your blood. At least 10,000 different proteins make you what you are and keep you that way.

Protein is made from twenty-plus basic building blocks called amino acids. Because we don’t store amino acids, our bodies make them in two different ways: either from scratch, or by modifying others. Nine amino acids—histidine, isoleucine, leucine, lysine, methionine, phenylalanine, threonine, tryptophan, and valine—known as the essential amino acids, must come from food.

The National Academy of Medicine recommends that adults get a minimum of 0.8 grams of protein for every kilogram of body weight per day, or just over 7 grams for every 20 pounds of body weight.

The National Academy of Medicine also sets a wide range for acceptable protein intake—anywhere from 10% to 35% of calories each day. Beyond that, there’s relatively little solid information on the ideal amount of protein in the diet or the healthiest target for calories contributed by protein. Individual needs will vary based on factors such as age, exercise level, health conditions, and overall dietary pattern. A registered dietitian can help determine one’s individual protein needs.

In an analysis conducted at Harvard among more than 130,000 men and women who were followed for up to 32 years, the percentage of calories from total protein intake was not related to overall mortality or to specific causes of death. However, the source of protein was important.

What are “complete” proteins, and how much do I need?

It’s important to note that millions of people worldwide, especially young children, don’t get enough protein due to food insecurity. The effects of protein deficiency and malnutrition range in severity from growth failure and loss of muscle mass to decreased immunity, weakening of the heart and respiratory system, and death.

However, it’s uncommon for healthy adults in the U.S. and most other developed countries to have a deficiency, because there’s an abundance of plant and animal-based foods full of protein. In fact, many in the U.S. are consuming more than enough protein, especially from animal-based foods.

#420 Dark Discussions at Cafe Infinity » Club Quotes - III » 2025-10-15 17:22:52

- Jai Ganesh

- Replies: 0

Club Quotes - III

1. Being at a club that supported me meant a lot. - David Beckham

2. To tell her that I joined the parachute club was too hard for me. I didn't want to trouble her; besides, I was not completely sure about the success of my new adventure. - Valentina Tereshkova

3. A lot of wasted energy in my life has been spent on sorting out problems and issues at Yorkshire cricket. Of course, I know I made mistakes along the way, but I care passionately about the club - I always have done and always will. Geoffrey Boycott

4. At the moment there are some England players who are the stars of their club teams, but not for their country. It's difficult to explain. - Diego Maradona

5. I know I have this level of celebrity, of fame, international, national, whatever you want to call it, but it's a pretty surreal thing to think sometimes that you're in the middle of another famous person's life and you think to yourself, 'How the hell did I get famous? What is this some weird club that we're in?' - Kevin Costner

6. Sugar Breeze, my favourite restaurant in Antigua, serves the best local food, while my local golf club, Cedar Valley, is where I always go for a drink. - Viv Richards

7. At our computer club, we talked about it being a revolution. Computers were going to belong to everyone, and give us power, and free us from the people who owned computers and all that stuff. - Steve Wozniak

8. I decided to create a sports club during the Soviet times. It was my dream. - Sergei Bubka.

#421 Jokes » Autumn Jokes - III » 2025-10-15 17:01:34

- Jai Ganesh

- Replies: 0

Q: How do leaves get from place to place?

A: With autumn-mobiles.

* * *

Q: How does an Elephant get out of a tree?

A: Sits on a leaf and waits till Autumn!

* * *

Q: What did a tree fighting with autumn say?

A: That's it, i'm leaving.

* * *

Q: What will fall on the lawn first?

A: An autumn leaf or a Christmas catalogue.

* * *

Q: What do you call a tree that doubts autumn?

A: Disbe-leaf.

* * *

Q: What is a tree's least favorite month?

A: Sep-timber!

* * *

#422 Re: Jai Ganesh's Puzzles » General Quiz » 2025-10-15 16:13:41

Hi,

#10611. What does the term in Geography Cartouche (cartography) mean?

#10612. What does the term in Geography Waterfall mean?

#423 Re: Jai Ganesh's Puzzles » English language puzzles » 2025-10-15 15:53:13

Hi,

#5807. What does the noun crease mean?

#5808. What does the noun credential mean?

#424 Re: Jai Ganesh's Puzzles » Doc, Doc! » 2025-10-15 15:26:23

Hi,

#2496. What does the medical term Skeletal muscle mean?

#425 Re: Jai Ganesh's Puzzles » 10 second questions » 2025-10-15 14:37:15

Hi,

#9765.