Math Is Fun Forum

You are not logged in.

- Topics: Active | Unanswered

#51 Dark Discussions at Cafe Infinity » College Quotes - V » 2026-01-19 16:43:32

- Jai Ganesh

- Replies: 0

College Quotes - V

1. My father was a trained accountant, a BCom from Sydenham College and a self-taught violinist. In the 1920s, when he was in his teens, he heard a great violinist, Jascha Heifetz, and he was so inspired listening to him that he bought himself a violin, and with a little help from an Italian teacher, he learned to play it. - Zubin Mehta

2. The goal of my University education was to get into a medical college and equip myself to run a hospital in Kumbakonam left behind by my father, M.K. Sambasivan, who died at a young age in 1936. - M. S. Swaminathan

3. I dropped out of college before graduation. I opted to begin work as an actress. - Sharmila Tagore

4. A coach, especially at a college level - much more at a college or high school level, than at a pro level - you're more of a teacher than an actual coach. - Matthew McConaughey

5. When I was in Class XI, I started preparing for medical college, and after that, the Miss India pageant. - Manushi Chhillar

6. I didn't play soccer; I played that other football in grade school through college. - Joe Biden

7. I was born in Harlem, raised in the South Bronx, went to public school, got out of public college, went into the Army, and then I just stuck with it. - Colin Powell

8. I went to Moorehouse College. There was no track and field there. - Edwin Moses

9. I wanted to go to medical school. But, I never got a college scholarship. - Edwin Moses.

#52 Jokes » Cheese Jokes - IX » 2026-01-19 16:22:12

- Jai Ganesh

- Replies: 0

Q: When do they smother a burrito in cheese?

A: In best queso scenario.

* * *

Q: What is a basketball players favorite kind of cheese?

A: Swish cheese!

* * *

Q: What did the cheese say when it looked in the mirror ?

A: Halloumi (Hello me.)

* * *

Q: What do you call a grilled cheese sandwich that's all up in your face?

A: Too close for comfort food.

* * *

Q: Do you want to hear a pizza joke?

A: Never mind it's to cheesey.

* * *

#53 Re: Dark Discussions at Cafe Infinity » crème de la crème » 2026-01-18 23:24:28

2413) Robert Hofstadter

Gist:

Work

Matter is composed of atoms with small nuclei surrounded by electrons. Robert Hofstadter developed apparatus for studying nuclei’s internal structure. A high-energy electron beam from an accelerator was directed towards nuclei and by examining the scattering of the electrons, he could investigate how charges were distributed. He could also investigate how the magnetic moment within the nuclei’s protons and neutrons was distributed. Nuclei were thereby proven not to be homogeneous, but to have internal structures.

Summary

Robert Hofstadter (born February 5, 1915, New York, New York, U.S.—died November 17, 1990, Stanford, California) was an American scientist who was a joint recipient of the Nobel Prize for Physics in 1961 for his investigations of protons and neutrons, which revealed the hitherto unknown structure of these particles. He shared the prize with Rudolf Ludwig Mössbauer of Germany.

Hofstadter was educated at Princeton University, where he earned a Ph.D. in 1938. As a physicist at the National Bureau of Standards during World War II, he was instrumental in developing the proximity fuse, which was used to detonate antiaircraft and other artillery shells. He joined the faculty of Princeton in 1946, where his principal scientific work dealt with the study of infrared rays, photoconductivity, and crystal and scintillation counters.

Hofstadter taught at Stanford University from 1950 to 1985. At Stanford he used a linear electron accelerator to measure and explore the constituents of atomic nuclei. At the time, protons, neutrons, and electrons were all thought to be structureless particles; Hofstadter discovered that protons and neutrons have a definite size and form. He was able to determine the precise size of the proton and neutron and provide the first reasonably consistent picture of the structure of the atomic nucleus. Hofstadter found that both the proton and neutron have a central, positively charged core surrounded by a double cloud of pi-mesons. Both clouds are positively charged in the proton, but in the neutron the inner cloud is negatively charged, thus giving a net zero charge for the entire particle.

Details

Robert Hofstadter (February 5, 1915 – November 17, 1990) was an American physicist. He was the joint winner of the 1961 Nobel Prize in Physics (together with Rudolf Mössbauer) "for his pioneering studies of electron scattering in atomic nuclei and for his consequent discoveries concerning the structure of nucleons".

Biography

Hofstadter was born in New York City on February 5, 1915, to Polish Jewish immigrants Louis Hofstadter, a salesman, and Henrietta, née Koenigsberg. He attended elementary and high schools in New York City and entered City College of New York, graduating with a B.S. degree magna cum laude in 1935 at the age of 20, and was awarded the Kenyon Prize in Mathematics and Physics. He also received a Charles A. Coffin Foundation Fellowship from the General Electric Company, which enabled him to attend graduate school at Princeton University, where he earned his M.S. and Ph.D. degrees at the age of 23. His doctoral dissertation was titled "Infra-red absorption by light and heavy formic and acetic acids." He did his post-doctoral research at the University of Pennsylvania and was an assistant professor at Princeton before joining Stanford University. Hofstadter taught at Stanford from 1950 to 1985.

In 1942 he married Nancy Givan (1920–2007), a native of Baltimore. They had three children: Laura, Molly (who was disabled and not able to communicate), and Pulitzer Prize-winner Douglas Hofstadter.

#54 Science HQ » Concave Lens » 2026-01-18 22:53:30

- Jai Ganesh

- Replies: 0

Concave Lens

Gist

A concave lens is a diverging lens, thinner in the middle and thicker at the edges, that curves inward, causing parallel light rays to spread out (diverge) after passing through it, forming virtual, upright, and diminished (smaller) images, commonly used in eyeglasses for nearsightedness and optical instruments.

A concave lens is also known as a diverging lens because it is shaped round inwards at the centre and bulges outwards through the edges, making the light diverge. They are used to treat myopia as they make faraway objects look smaller than they are.

A concave lens corrects myopia by being thinner at the center and thicker at the edge. It diverges light rays entering the eye so they focus a little further back, landing directly on the retina instead of in front of it.

Summary

A concave lens is a lens that diverges a straight light beam from the source to a diminished, upright, virtual image. It can form both real and virtual images. Concave lenses have at least one surface curved inside. A concave lens is also known as a diverging lens because it is shaped round inwards at the centre and bulges outwards through the edges, making the light diverge. They are used to treat myopia as they make faraway objects look smaller than they are.

Uses of Concave Lens

Some uses of the concave lens are listed below:

Used in Telescope

Concave lenses are used in telescopes and binoculars to magnify objects. As a convex lens creates blurs and distortion, telescope and binocular manufacturers install concave lenses before or in the eyepiece so that a person can focus more clearly.

Used in Eye Glasses

Concave lenses are most commonly used to correct myopia which is also called nearsightedness. The eyeball of a person suffering from myopia is too long, and the images of faraway objects fall short of the retina. Therefore, concave lenses are used in glasses which correct the shortfall by spreading out the light rays before it reaches the eyeball. This enables the person to see far away objects more clearly.

Used in Peepholes

Peepholes or door viewers are security devices that give a panoramic view if objects outside walls or doors. A concave lens is used to minimize the proportions of the objects and gives a wider view of the object or area.

Details

Concave lenses are one of the many lenses used in optics. They help create some of the most important equipment you use in your everyday life. These lenses come in various types and have plenty of applications. This article contains all you need to know about concave lenses, such as the different types and how they are applied.

What Is a Concave Lens?

A concave lens bends light inward so that the resulting image is smaller and more vertical than the original. Furthermore, it can create an actual or virtual image. Concave lenses contain at least one face that is curved inward. Another name for these lenses is diverging lenses, and this is because they bulge outward at their borders and are spherical in their centers, causing light to spread out rather than focus.

Types of Concave Lenses:

Bi-Concave Lenses

These types of lenses are also called double-concave lenses. Both sides of a bi-concave lens have equal radius curvature and, similar to plano-concave lenses, can deviate from incident light.

Plano-Concave Lenses

A plano-concave lens works like a bi-concave lens. However, these lenses have one flat face and one concave. Furthermore, plano-concave lenses have a negative focal length.

Convexo-Concave Lenses

A convexo-concave lens has one convex surface and one concave surface. That said, the convex surface has a higher curvature than the concave surface, which leads to the lens being thickest in the center.

Applications of Concave Lenses:

Corrective Lenses

Correction of myopia (short-sightedness) typically involves the use of concave lenses. Myopic eyes have longer than average eyeballs, which causes images of a distant object to be projected onto the fovea instead of the retina.

Glasses with concave lenses can fix this by spreading the incoming light out before reaching the eye. In doing so, the patient can perceive further away objects with more clarity.

Binoculars and Telescopes

Binoculars allow users to see distant objects, making them appear closer. They are constructed from convex and concave lenses. The convex lens zooms in on the object, while the concave lens is used to focus the image properly.

Telescopes function similarly in that they have convex and concave lenses. They are used to observe extremely distant objects, such as planets. The convex lens serves as the magnification lens, while the concave lens serves as the eyepiece.

Lasers

Laser beams are used in a variety of devices, including scanners, DVD players, and medical instruments. Even though lasers are incredibly concentrated sources of light, they must be spread out for usage in practical applications. As a result, the laser beam is widened by a series of tiny concave lenses, allowing for pinpoint targeting of a specific location.

Flashlights

Flashlights also make use of concave lenses to increase the output of the light they use. Light converges on the lens’ hollowed side and spreads out on the other. This broadens the light’s beam by expanding the source’s diameter.

Cameras

Camera manufacturers frequently utilize lenses that possess concave and convex surfaces to enhance image quality. Convex lenses are the most used lenses in cameras, and chromatic aberrations can occur when they are used. Fortunately, this issue can be solved by combining concave and convex lenses.

Peepholes

Peepholes, often called door viewers, are safety features that allow a full view of what’s on the other side of a wall or door. While looking at an object or area, a concave lens will make it appear smaller and provide a wider perspective.

Conclusion

Well, there you have it. All there is to know about concave lenses. They are lenses with at least one surface curved inward. These lenses are able to bend light inward and make images appear upright and smaller. You can find them used in several contraptions, such as cameras, flashlights, telescopes, and others.

Additional Information

The word "lens" owes its origin to the Latin word for lentils, the tiny beans that have from ancient times been an important ingredient in the cuisine of the Mediterranean region. The convex shape of lentils resulted in their Latin name being coined for glass possessing the same shape.

Because of the way in which lenses refract light that strikes them, they are used to concentrate or disperse light. Light entering a lens can be altered in many different ways according, for example, to the composition, size, thickness, curvature and combination of the lens used. Many different kinds of lenses are manufactured for use in such devices as cameras, telescopes, microscopes and eyeglasses. Copying machines, image scanners, optical fiber transponders and cutting-edge semiconductor production equipment are other more recent devices in which the ability of lenses to diffuse or condense light is put to use.

Convex and Concave Lenses Used in Eyeglasses

Lenses may be divided broadly into two main types: convex and concave. Lenses that are thicker at their centers than at their edges are convex, while those that are thicker around their edges are concave. A light beam passing through a convex lens is focused by the lens on a point on the other side of the lens. This point is called the focal point. In the case of concave lenses, which diverge rather than condense light beams, the focal point lies in front of the lens, and is the point on the axis of the incoming light from which the spread light beam through the lens appears to originate.

Concave Lenses Are for the Nearsighted, Convex for the Farsighted

Concave lenses are used in eyeglasses that correct nearsightedness. Because the distance between the eye's lens and retina in nearsighted people is longer than it should be, such people are unable to make out distant objects clearly. Placing concave lenses in front of a nearsighted eye reduces the refraction of light and lengthens the focal length so that the image is formed on the retina.

Convex lenses are used in eyeglasses for correcting farsightedness, where the distance between the eye's lens and retina is too short, as a result of which the focal point lies behind the retina. Eyeglasses with convex lenses increase refraction, and accordingly reduce the focal length.

Telephoto Lenses Are Combinations of Convex and Concave Lenses

Most optical devices make use of not just one lens, but of a combination of convex and concave lenses. For example, combining a single convex lens with a single concave lens enables distant objects to be seen in more detail. This is because the light condensed by the convex lens is once more refracted into parallel light by the concave lens. This arrangement made possible the

Galilean telescope, named after its 17th century inventor, Galileo.

Adding a second convex lens to this combination produces a simple telephoto lens, with the front convex and concave lens serving to magnify the image, while the rear convex lens condenses it.

Adding a further two pairs of convex/concave lenses and a mechanism for adjusting the distance between the single convex and concave lenses enables the modification of magnification over a continuous range. This is how zoom lenses work.

Lenses that Correct the Blurring of Colors

The focused image through a single convex lens is actually very slightly distorted or blurred in a phenomenon known as lens aberration. The reason why camera and microscope lenses combine so many lens elements is to correct this aberration to obtain sharp and faithful images.

One common lens aberration is chromatic aberration. Ordinary light is a mixture of light of many different colors, i.e. wavelengths. Because the refractive index of glass to light differs according to its color or wavelength, the position in which the image is formed differs according to color, creating a blurring of colors. This chromatic aberration can be canceled out by combining convex and concave lenses of different refractive indices.

Low-chromatic-aberration Glass

Special lenses, known as fluorite lenses, and boasting very low dispersion of light, have been developed to resolve the issue of chromatic aberration. Fluorite is actually calcium fluoride (CaF2), crystals of which exist naturally. Towards the end of the 1960s, Canon developed the technology for artificially creating fluorite crystals, and in the latter half of the 1970s we achieved the first UD (Ultra Low Dispersion) lenses incorporating low-dispersion optical glass. In the 1990s, we further improved this technology to create Super UD lenses. A mixture of fluorite, UD and Super UD elements are used in today's EF series telephoto lenses.

Aspherical Lenses for Correcting Spherical Aberration

There are four other key types of aberration: spherical and coma aberration, astigmatism, curvature of field, and distortion. Together with chromatic aberration, these phenomena make up what are known as Seidel's five aberrations. Spherical aberration refers to the blurring that occurs as a result of light passing through the periphery of the lens converging at a point closer to the lens than light passing through the center. Spherical aberration is unavoidable in a single spherical lens, and so aspherical lenses, whose curvature is slightly modified towards the periphery, were developed to reduce it.

In the past, correcting spherical aberration required the combination of many different lens elements, and so the invention of aspherical lenses enabled a substantial reduction in the overall number of elements required for optical instruments.

Lenses that Make Use of the Diffraction of Light

Because light is a wave, when it passes through a small hole, it is diffracted outwards towards shadow areas. This phenomenon can be used to advantage to control the direction of light by making concentric sawtooth-shaped grooves in the surface of a lens. Such lenses are known as diffractive optical elements. These elements are ideal for the small and light lenses that focus the laser beams used in CD and DVD players. Because the lasers used in electronic devices produce light of a single wavelength, a single-layer diffractive optical element is sufficient to achieve accurate light condensation.

Chromatic aberration caused by diffraction on the one hand, and refraction on the other arise in completely opposite ways. Skillful exploitation of this fact enables the creation of small and light telephoto lenses.

Unlike pickup lenses for CD and DVD players, incorporating simple diffractive optical elements into SLR camera lenses results in the generation of stray light. However this problem can be resolved by using laminated diffractive optical elements, in which two diffractive optical elements are aligned within a precision of a few micrometers.

If this arrangement is then combined with a refractive convex lens, chromatic aberration can be corrected. Smaller and lighter than the purely refractive lenses that have been commonly used until now, these diffractive lenses are now being increasingly used by sports and news photographers.

The larger the mirror of an astronomical telescope, the greater will be the telescope's ability to collect light. The primary mirror of the Subaru telescope, built by Japan's National Astronomical Observatory, has a diameter of 8.2 m, making Subaru the world's largest optical telescope, and one that boasts very high resolution, with a diffraction limit of only 0.23 arc seconds. This is good enough resolution to be able to make out a small coin placed on the tip of Mt. Fuji from as far away as Tokyo. Moreover, the Subaru telescope is about 600 million times more sensitive to light than the human eye. Even the largest telescopes until Subaru were unable to observe stars more than about one billion light years away, but Subaru can pick up light from galaxies lying 15 billion light years away. Light from 15 billion light years away and beyond is, in fact, thought to be light produced by the "big bang" that supposedly gave birth to the universe.

With a diameter of 52 cm and total weight of 170 kg, this high-precision lens unit is the fruit of Canon's lens design and manufacturing technologies. Stellar light picked up by the world's largest mirror and passed through this unit is focused on a giant CCD unit consisting of ten 4,096 x 2,048 pixel CCDs, producing images of 80 megapixels.

#55 This is Cool » Earthquake » 2026-01-18 22:07:46

- Jai Ganesh

- Replies: 0

Earthquake

Gist

What is an earthquake? An earthquake is the sudden release of strain energy in the Earth's crust, resulting in waves of shaking that radiate outwards from the earthquake source. When stresses in the crust exceed the strength of the rock, it breaks along lines of weakness, either a pre-existing or new fault plane.

Earthquakes are primarily caused by geological faults, but also by volcanism, landslides, and other seismic events. Significant historical earthquakes include the 1976 Tangshan earthquake in China, with over 300,000 fatalities, and the 1960 Valdivia earthquake in Chile, the largest ever recorded at 9.5 magnitude.

Summary

An earthquake is any sudden shaking of the ground caused by the passage of seismic waves through Earth’s rocks. Seismic waves are produced when some form of energy stored in Earth’s crust is suddenly released, usually when masses of rock straining against one another suddenly fracture and “slip.” Earthquakes occur most often along geologic faults, narrow zones where rock masses move in relation to one another. The major fault lines of the world are located at the fringes of the huge tectonic plates that make up Earth’s crust.

Little was understood about earthquakes until the emergence of seismology at the beginning of the 20th century. Seismology, which involves the scientific study of all aspects of earthquakes, has yielded answers to such long-standing questions as why and how earthquakes occur.

About 50,000 earthquakes large enough to be noticed without the aid of instruments occur annually over the entire Earth. Of these, approximately 100 are of sufficient size to produce substantial damage if their centres are near areas of habitation. Very great earthquakes occur on average about once per year. Over the centuries they have been responsible for millions of deaths and an incalculable amount of damage to property.

The nature of earthquakes:

Causes of earthquakes

Earth’s major earthquakes occur mainly in belts coinciding with the margins of tectonic plates. This has long been apparent from early catalogs of felt earthquakes and is even more readily discernible in modern seismicity maps, which show instrumentally determined epicentres. The most important earthquake belt is the Circum-Pacific Belt, which affects many populated coastal regions around the Pacific Ocean—for example, those of New Zealand, New Guinea, Japan, the Aleutian Islands, Alaska, and the western coasts of North and South America. It is estimated that 80 percent of the energy presently released in earthquakes comes from those whose epicentres are in this belt. The seismic activity is by no means uniform throughout the belt, and there are a number of branches at various points. Because at many places the Circum-Pacific Belt is associated with volcanic activity, it has been popularly dubbed the “Pacific Ring of Fire.”

A second belt, known as the Alpide Belt, passes through the Mediterranean region eastward through Asia and joins the Circum-Pacific Belt in the East Indies. The energy released in earthquakes from this belt is about 15 percent of the world total. There also are striking connected belts of seismic activity, mainly along oceanic ridges—including those in the Arctic Ocean, the Atlantic Ocean, and the western Indian Ocean—and along the rift valleys of East Africa. This global seismicity distribution is best understood in terms of its plate tectonic setting.

Natural forces

Earthquakes are caused by the sudden release of energy within some limited region of the rocks of the Earth. The energy can be released by elastic strain, gravity, chemical reactions, or even the motion of massive bodies. Of all these the release of elastic strain is the most important cause, because this form of energy is the only kind that can be stored in sufficient quantity in the Earth to produce major disturbances. Earthquakes associated with this type of energy release are called tectonic earthquakes.

Details

An earthquake, also called a quake, tremor, or temblor, is the shaking of the Earth's surface resulting from a sudden release of energy in the lithosphere that creates seismic waves. Earthquakes can range in intensity, from those so weak they cannot be felt, to those violent enough to propel objects and people into the air, damage critical infrastructure, and wreak destruction across entire cities. The seismic activity of an area is the frequency, type, and size of earthquakes experienced over a particular time. The seismicity at a particular location in the Earth is the average rate of seismic energy release per unit volume.

In its most general sense, the word earthquake is used to describe any seismic event that generates seismic waves. Earthquakes can occur naturally or be induced by human activities, such as mining, fracking, and nuclear weapons testing. The initial point of rupture is called the hypocenter or focus, while the ground level directly above it is the epicenter. Earthquakes are primarily caused by geological faults, but also by volcanism, landslides, and other seismic events.

Significant historical earthquakes include the 1976 Tangshan earthquake in China, with over 300,000 fatalities, and the 1960 Valdivia earthquake in Chile, the largest ever recorded at 9.5 magnitude. Earthquakes result in various effects, such as ground shaking and soil liquefaction, leading to significant damage and loss of life. When the epicenter of a large earthquake is located offshore, the seabed may be displaced sufficiently to cause a tsunami. Earthquakes can trigger landslides. Earthquakes' occurrence is influenced by tectonic movements along faults, including normal, reverse (thrust), and strike-slip faults, with energy release and rupture dynamics governed by the elastic-rebound theory.

Efforts to manage earthquake risks involve prediction, forecasting, and preparedness, including seismic retrofitting and earthquake engineering to design structures that withstand shaking. The cultural impact of earthquakes spans myths, religious beliefs, and modern media, reflecting their profound influence on human societies. Similar seismic phenomena, known as marsquakes and moonquakes, have been observed on other celestial bodies, indicating the universality of such events beyond Earth.

Additional Information:

What is an Earthquake?

An earthquake is an intense shaking of Earth’s surface. The shaking is caused by movements in Earth’s outermost layer.

Why Do Earthquakes Happen?

Although the Earth looks like a pretty solid place from the surface, it’s actually extremely active just below the surface. The Earth is made of four basic layers: a solid crust, a hot, nearly solid mantle, a liquid outer core and a solid inner core.

The solid crust and top, stiff layer of the mantle make up a region called the lithosphere. The lithosphere isn’t a continuous piece that wraps around the whole Earth like an eggshell. It’s actually made up of giant puzzle pieces called tectonic plates. Tectonic plates are constantly shifting as they drift around on the viscous, or slowly flowing, mantle layer below.

This non-stop movement causes stress on Earth’s crust. When the stresses get too large, it leads to cracks called faults. When tectonic plates move, it also causes movements at the faults. An earthquake is the sudden movement of Earth’s crust at a fault line.

The location where an earthquake begins is called the epicenter. An earthquake’s most intense shaking is often felt near the epicenter. However, the vibrations from an earthquake can still be felt and detected hundreds, or even thousands of miles away from the epicenter.

How Do We Measure Earthquakes?

The energy from an earthquake travels through Earth in vibrations called seismic waves. Scientists can measure these seismic waves on instruments called seismometer. A seismometer detects seismic waves below the instrument and records them as a series of zig-zags.

Scientists can determine the time, location and intensity of an earthquake from the information recorded by a seismometer. This record also provides information about the rocks the seismic waves traveled through.

Do Earthquakes Only Happen on Earth?

Earthquake is a name for seismic activity on Earth, but Earth isn’t the only place with seismic activity. Scientists have measured quakes on Earth's Moon, and see evidence for seismic activity on Mars, Venus and several moons of Jupiter, too!

NASA’s InSight mission took a seismometer to Mars to study seismic activity there, known as marsquakes. On Earth, we know that different materials vibrate in different ways. By studying the vibrations from marsquakes, scientists hope to figure out what materials are found on the inside of Mars.

InSight is collecting tons of information about what Mars is like under the surface. These new discoveries will help us understand more about how planets like Mars—and our home, Earth—came to be.

#56 Dark Discussions at Cafe Infinity » College Quotes - IV » 2026-01-18 18:05:26

- Jai Ganesh

- Replies: 0

College Quotes - IV

1. I had a difficult time hearing my own inner voice about what I wanted to be in this life, because there were all these perfect examples of what a man actually does. The notion is that he goes to college, gets married and provides. That's what a man does. - Kevin Costner

2. In my final year of college, I was interning with L'Oreal, when during one of the photo shoots, a photographer suggested I become a model. I was working under Smira Bakshi, who was this really cool chick, as she was loaded, had her fun, and was successful. I basically aspired to be her. - Kajal Aggarwal

3. For me, education has never been simply a policy issue - it's personal. Neither of my parents and hardly anyone in the neighborhood where I grew up went to college. But thanks to a lot of hard work and plenty of financial aid, I had the opportunity to attend some of the finest universities in this country. - Michelle Obama

4. It was a very long and hard decision. My dad kept telling me, 'You can always go to college, but you can't always go pro.' That made sense to me. - Simone Biles

5. In college I never realized the opportunities available to a pro athlete. I've been given the chance to meet all kinds of people, to travel and expand my financial capabilities, to get ideas and learn about life, to create a world apart from basketball. - Michael Jordan

6. My parents being Bengali, we always had music in our house. My nani was a trained classical singer, who taught my mum, who, in turn, was my first teacher. Later I would travel almost 70 kms to the nearest town, Kota, to learn music from my guru Mahesh Sharmaji, who was also the principal of the music college there. - Shreya Ghoshal

7. When my friends in college had crushes, I used to think something is wrong with them. I just chill out. - Anushka Sharma

8. After my graduation from Sydenham College with a degree in Commerce, I was spotted by late Sunil Dutt, my idol, to act in films. - Vinod Khanna.

#57 Jokes » Cheese Jokes - VIII » 2026-01-18 17:36:16

- Jai Ganesh

- Replies: 0

Q: Why did the wheel act so bossy?

A: Cause he was the "Big Cheese."

* * *

Q: What is a lions favourite cheese?

A: Roar-quefort.

* * *

Q: What did Gorgonzola say to Cheddar?

A: Lookin' Sharp.

* * *

Q: Did you hear what happened when the decorator painted his wife with cheese?

A: He double Gloucester!

* * *

Q: Whats the best cheese to coax a bear down a mountain?

A: Camembert (Come On Bear).

* * *

#58 Re: Jai Ganesh's Puzzles » General Quiz » 2026-01-18 17:26:18

Hi,

#10705. What does the term in Biology Ethology mean?

#10706. What does the term in Biology Eukaryote mean?

#59 Re: Jai Ganesh's Puzzles » English language puzzles » 2026-01-18 17:09:43

Hi,

#5901. What does the noun tragicomedy mean?

#5902. What does the noun trailer mean?

#60 Re: Jai Ganesh's Puzzles » Doc, Doc! » 2026-01-18 16:57:37

Hi,

#2547. What does the medical term Gas gangrene mean?

#61 Re: Jai Ganesh's Puzzles » 10 second questions » 2026-01-18 16:48:21

Hi,

#9831.

#62 Re: Jai Ganesh's Puzzles » Oral puzzles » 2026-01-18 16:34:59

Hi,

#6325.

#63 Re: Exercises » Compute the solution: » 2026-01-18 16:20:39

Hi,

2682.

#64 Re: Jai Ganesh's Puzzles » General Quiz » 2026-01-17 22:45:13

Hi,

#10703. What does the term in Biology Essential nutrient mean?

#10704. What does the term in Biology Estrogen mean?

#65 Re: Jai Ganesh's Puzzles » Doc, Doc! » 2026-01-17 22:25:23

Hi,

#2546. What does the medical term Peripheral neuropathy mean?

#66 Re: Jai Ganesh's Puzzles » English language puzzles » 2026-01-17 22:13:08

Hi,

#5899. What does the noun qualm mean?

#5900. What does the noun quarry mean?

#67 Re: Dark Discussions at Cafe Infinity » crème de la crème » 2026-01-17 21:14:52

2412) Maurice Wilkins

Gist:

Work

During the 1930s, a number of laboratories began to use a method called x-ray crystallography to map large, biologically important molecules. Maurice Wilkins and Rosalind Franklin worked to determine the structure of the DNA molecule in the early 1950s at King's College in London. While they did not succeed in mapping the structure, their results–not least of all Franklin's x-ray diffraction images–were important in Francis Crick's and James Watson's eventual unlocking of the mystery–a long spiral with twin threads.

Summary

Maurice Wilkins (born December 15, 1916, Pongaroa, New Zealand—died October 6, 2004, London, England) was a New Zealand-born British biophysicist whose X-ray diffraction studies of deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) proved crucial to the determination of DNA’s molecular structure by James D. Watson and Francis Crick. For this work the three scientists were jointly awarded the 1962 Nobel Prize for Physiology or Medicine.

Wilkins, the son of a physician (who was originally from Dublin), was educated at King Edward’s School in Birmingham, England, and St. John’s College, Cambridge. His doctoral thesis, completed for the University of Birmingham in 1940, contained his original formulation of the electron-trap theory of phosphorescence and thermoluminescence. He participated for two years during World War II in the Manhattan Project at the University of California, Berkeley, working on mass spectrograph separation of uranium isotopes for use in the atomic bomb.

Upon his return to Great Britain, Wilkins lectured at the University of St. Andrews in Scotland. In 1946 he joined the Medical Research Council’s Biophysics Unit at King’s College in London. In 1955 he became its deputy director, and from 1970 to 1980 he served as the unit’s director. There he began the series of investigations that led ultimately to his X-ray diffraction studies of DNA. Wilkins headed a group that included Rosalind Franklin, a crystallographer who produced DNA pictures that also aided the work of Crick and Watson. Wilkins later applied X-ray diffraction techniques to the study of ribonucleic acid.

At King’s College proper, Wilkins was professor of molecular biology (1963–70) and of biophysics (1970–81) and emeritus professor thereafter. While there he published literature on light microscopy techniques for cytochemical research. His autobiography, The Third Man of the Double Helix, was published in 2003.

Details

Maurice Hugh Frederick Wilkins (15 December 1916 – 5 October 2004) was a New Zealand-born British biophysicist and Nobel laureate whose research spanned multiple areas of physics and biophysics, contributing to the scientific understanding of phosphorescence, isotope separation, optical microscopy, and X-ray diffraction. He is most noted for initiating and leading early X-ray diffraction studies on DNA at King's College London, and for his pivotal role in enabling the discovery of the double helix structure of DNA.

Wilkins began investigating nucleic acids in 1948. By 1950, he and his team had produced some of the first high-quality X-ray diffraction images of DNA fibers. He presented this work in 1951 at a conference in Naples, where it significantly influenced James Watson, prompting Watson to pursue DNA structure research with Francis Crick.

In 1951, Rosalind Franklin joined King’s College and was assigned to the same DNA project, though without a clear delineation of leadership. Tensions developed due to overlapping roles and lack of administrative clarity. During this period, Franklin and graduate student Raymond Gosling captured the high-resolution Photo 51, a diffraction image of B-form DNA. In early 1953, John Randall instructed Gosling to hand it over to Wilkins. Wilkins, in turn, showed it to Watson—without Franklin's consent. This action has been the subject of significant ethical and historiographical debate.

Using insights from Photo 51 and prior data—including Wilkins' own diffraction studies—Watson and Crick constructed their double helix model in March 1953. Wilkins simultaneously continued experimental validation, producing confirmatory diffraction images published in the same issue of Nature.

Wilkins' contributions were not limited to verification. He had led the DNA diffraction research at King’s before Franklin’s arrival, initiated the methods that led to Photo 51, and played a central role in sharing data and coordinating the laboratory’s DNA efforts—roles often underrepresented in historical summaries.

In later years, Wilkins extended his studies to RNA structure and worked on the biological effects of radiation.

He shared the 1962 Nobel Prize for Physiology or Medicine with Watson and Crick, awarded "for their discoveries concerning the molecular structure of nucleic acids and its significance for information transfer in living material". Although Franklin had died in 1958 and was therefore ineligible, Wilkins acknowledged her work in his writings and interviews.

In 2000, King's College London named one of its science buildings the Franklin-Wilkins Building to honor their contributions. Scholarly reassessments in recent decades have increasingly recognized Wilkins’ role as foundational to the DNA discovery effort.

#68 Re: This is Cool » Miscellany » 2026-01-17 20:47:09

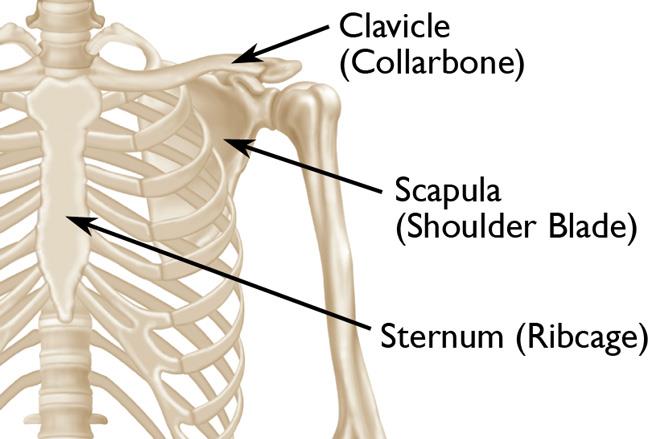

2474) Clavicle

Clavicle

Gist

A clavicle, or collarbone, is a slender, S-shaped bone that connects the breastbone (sternum) to the shoulder blade (scapula), forming part of the shoulder girdle and linking the arm to the body's core. It's the only long bone that lies horizontally, providing stability, protecting nerves and blood vessels, and allowing for a wide range of arm motion, though it's also the body's most commonly fractured bone, often from falls or impacts.

The clavicle (collarbone) is generally considered the weakest bone due to its thin, curved structure and exposed location, making it highly prone to fractures from falls or impacts, while the stapes (stirrup bone) in the middle ear is the smallest and most delicate, though rarely fractured because of its protection. The clavicle's vulnerability comes from its role as a strut connecting the arm to the body, absorbing force, but its slenderness makes it susceptible to snapping.

Summary

Clavicle is the curved anterior bone of the shoulder (pectoral) girdle in vertebrates; it functions as a strut to support the shoulder.

The clavicle is present in mammals with prehensile forelimbs and in bats, and it is absent in sea mammals and those adapted for running. The wishbone, or furcula, of birds is composed of the two fused clavicles; a crescent-shaped clavicle is present under the pectoral fin of some fish. In humans the two clavicles, on either side of the anterior base of the neck, are horizontal, S-curved rods that articulate laterally with the outer end of the shoulder blade (the acromion) to help form the shoulder joint; they articulate medially with the breastbone (sternum). Strong ligaments hold the clavicle in place at either end; the shaft gives attachment to muscles of the shoulder girdle and neck.

The clavicle may be congenitally reduced or absent; its robustness varies with degree of muscle development. The clavicle is a common site of fracture, particularly at the midsection of the bone; horizontal impact to the shoulder, such as from a fall or trauma, is a common cause.

Details

The clavicle, collarbone, or keybone is a slender, S-shaped long bone approximately 15 centimetres (6 in) long that serves as a strut between the shoulder blade and the sternum (breastbone). There are two clavicles, one on each side of the body. The clavicle is the only long bone in the body that lies horizontally. Together with the shoulder blade, it makes up the shoulder girdle. It is a palpable bone and, in people who have less fat in this region, the location of the bone is clearly visible. It receives its name from Latin clavicula 'little key' because the bone rotates along its axis like a key when the shoulder is abducted. The clavicle is the most commonly fractured bone. It can easily be fractured by impacts to the shoulder from the force of falling on outstretched arms or by a direct hit.

Structure

The collarbone is a thin doubly curved long bone that connects the arm to the trunk of the body. Located directly above the first rib, it acts as a strut to keep the scapula in place so that the arm can hang freely. At its rounded medial end (sternal end), it articulates with the manubrium of the sternum (breastbone) at the sternoclavicular joint. At its flattened lateral end (acromial end), it articulates with the acromion, a process of the scapula (shoulder blade), at the acromioclavicular joint.

The rounded medial region (sternal region) of the shaft has a long curve laterally and anteriorly along two-thirds of the entire shaft. The flattened lateral region (acromial region) of the shaft has an even larger posterior curve to articulate with the acromion of the scapula. The medial region is the longest clavicular region as it takes up two-thirds of the entire shaft. The lateral region is both the widest clavicular region and thinnest clavicular region. The lateral end has a rough inferior surface that bears a ridge, the trapezoid line, and a slight rounded projection, the conoid tubercle (above the coracoid process). These surface features are attachment sites for muscles and ligaments of the shoulder.

It can be divided into three parts: medial end, lateral end, and shaft.

Medial end

The medial end is also known as the sternal end. It is quadrangular and articulates with the clavicular notch of the manubrium of the sternum to form the sternoclavicular joint. The articular surface extends to the inferior aspect for articulation with the first costal cartilage.

Lateral end

The lateral end is also known as the acromial end. It is flat from above downward. It bears a facet that articulates with the shoulder to form the acromioclavicular joint. The area surrounding the joint gives an attachment to the joint capsule. The anterior border is concave forward and the posterior border is convex backward.

Shaft

The shaft is divided into two main regions, the medial region, and the lateral region. The medial region is also known as the sternal region, it is the longest clavicular region as it takes up two-thirds of the entire shaft. The lateral region is also known as the acromial region, it is both the widest clavicular region and thinnest clavicular region.

Lateral region of the shaft

The lateral region of the shaft has two borders and two surfaces.

* the anterior border is concave forward and gives origin to the deltoid muscle.

* the posterior border is convex and gives attachment to the trapezius muscle.

* the inferior surface has a ridge called the trapezoid line and a tubercle; the conoid tubercle for attachment with the trapezoid and the conoid ligament, part of the coracoclavicular ligament that serves to connect the collarbone with the coracoid process of the scapula.

Development

The collarbone is the first bone to begin the process of ossification (laying down of minerals onto a preformed matrix) during development of the embryo, during the fifth and sixth weeks of gestation. However, it is one of the last bones to finish ossification at about 21–25 years of age. Its lateral end is formed by intramembranous ossification while medially it is formed by endochondral ossification. It consists of a mass of cancellous bone surrounded by a compact bone shell. The cancellous bone forms via two ossification centres, one medial and one lateral, which fuse later on. The compact forms as the layer of fascia covering the bone stimulate the ossification of adjacent tissue. The resulting compact bone is known as a periosteal collar.

The collarbone has a medullary cavity (marrow cavity) in its medial two-thirds. It is made up of spongy cancellous bone with a shell of compact bone. It is a dermal bone derived from elements originally attached to the skull.

Variation

The shape of the clavicle varies more than most other long bones. It is occasionally pierced by a branch of the supraclavicular nerve. In males the clavicle is usually longer and larger than in females. A study measuring 748 males and 252 females saw a difference in collarbone length between age groups 18–20 and 21–25 of about 6 and 5 mm (0.24 and 0.20 in) for males and females respectively.

The left clavicle is usually longer and weaker than the right clavicle.

The collarbones are sometimes partly or completely absent in cleidocranial dysostosis.

The levator claviculae muscle, present in 2–3% of people, originates on the transverse processes of the upper cervical vertebrae and is inserted in the lateral half of the clavicle.

Additional Information

Your clavicle (collarbone) is a part of your skeletal system that connects your arm to your body. Ligaments connect this long, thin bone to your sternum and shoulder. Your clavicle is prone to injuries like a clavicle fracture, dislocated shoulder and separated shoulder. Falls are a top cause of clavicle injuries.

Overview:

What is a clavicle?

Your clavicle (collarbone) is a long, slightly curved bone that connects your arm to your body. You’ll find one on both sides of the base of your neck. The bones help keep your shoulder blade in the correct position as you move.

The word “clavicle” comes from the Latin “clavicula,” which translates to “little key.” The bone is actually shaped a bit like an old-fashioned key. And it works in much the same way. When you rotate a key, it moves the lock. Similarly, when you lift your arm, your clavicle rotates along its axis to allow movement.

Because of its location and role in shoulder movement, your clavicle bone is prone to injury. These injuries are common in contact sports, falls (especially when you put your arm out to catch yourself) and trauma like car accidents. Sometimes, babies can get a clavicle injury during birth.

What are clavicles made of?

Your clavicles are bones, and bones are made of layers of cells and proteins. They have a hard outer layer or shell, and an inner layer of spongy bone (cancellous bone) tissue.

What is its purpose?

Your clavicles are long bones that support your upper body and play an important role in how you move. They hold your shoulder in place, allowing you to transfer weight from your upper body to your head, neck, back and chest (your axial skeleton).

Anatomy:

Where is the clavicle located?

In an adult, each clavicle is about 6 inches long and runs along the top of your chest at the front of your shoulder. It runs horizontally (from side to side). Strong bands of tissue (ligaments) connect your sternum (breast bone) in the middle of your ribcage to your shoulder blade (scapula).

Conditions and Disorders:

What are the common conditions and disorders that affect the clavicle?

Your clavicle is long and narrow. It lies right under the surface of your skin, making it prone to fractures and injuries. Active children, teens and those who play contact sports are more prone to injuries like dislocated shoulders. Adults, especially those who are older, are more prone to falls that cause broken clavicles.

Types of clavicle injuries include:

* Clavicle fracture. Your clavicle bone breaks in one place or several places (comminuted fracture). A healthcare provider calls it a displaced clavicle fracture when the ends of the broken bones don’t line up.

* Separated shoulder. You tear the ligament connecting your clavicle and shoulder blade, and they separate. A shoulder separation can put your clavicle out of alignment. It causes pain and a bump underneath your skin.

Other conditions that can affect your clavicle include:

* Osteoarthritis.

* Bone cancer.

* Osteomyelitis.

* Thoracic outlet syndrome.

Common symptoms of clavicle conditions

Pain is the most common symptom of clavicle conditions. Other symptoms include:

* Swelling.

* Inability to lift your arm or grasp items.

* Bruising or discoloration.

* A lump or bump near your clavicle.

If you think you’ve broken your clavicle, go to the emergency room (ER). A healthcare provider should diagnose and treat a clavicle fracture as soon as possible to make sure it heals correctly.

How common are clavicle injuries?

A broken clavicle is a common injury in adults. It accounts for about 5% of (1 in 20) adult fractures.

Common tests to check for clavicle conditions

If you have symptoms of a clavicle injury or another clavicle condition, a healthcare provider might suggest one or more of the following imaging tests:

* X-ray.

* Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI).

* A computed tomography (CT) scan.

Common treatments for the clavicle

Treatment for clavicle pain or injury depends on what sort of problem you’re having. It might include:

* Resting or immobilizing your shoulder to allow the bone to heal. Your healthcare provider might give you a sling.

* Ice packs for 20 minutes at a time.

* Over-the-counter (OTC) pain relievers like aspirin, ibuprofen or acetaminophen.

If you’ve fractured your clavicle, you might need surgery to get your bones back where they belong and secure them in place.

Care:

How can I protect my clavicle?

These steps can keep your clavicle and the rest of your skeletal system healthy and strong:

* Do weight-bearing exercises like walking, jogging or tennis for at least 30 minutes most days of the week.

* Get enough vitamin D and calcium in your diet to build strong bones.

* Lift weights or do other resistance exercises to strengthen bones.

* Prevent falls by being cautious on stairs and removing tripping hazards.

* Quit smoking and cut back on alcohol.

* Wear protective gear when participating in contact sports (shoulder pads) and physical activities like biking (helmet).

#69 Jokes » Cheese Jokes - VII » 2026-01-17 17:55:08

- Jai Ganesh

- Replies: 0

Q: Which is the Richest Cheese in the world?

A: Paris Stilton.

* * *

Q: What do you call an oriental cheese?

A: Parm-asian.

* * *

Q: What's the most popular American cheese sitcom?

A: Curd Your Enthusiasm.

* * *

Q: Why does cheese look normal?

A: Because everyone else on the plate is crackers.

* * *

Q: What did the street cheese say after he got attacked by several blades?

A: I've felt grater.

* * *

#70 Dark Discussions at Cafe Infinity » College Quotes - III » 2026-01-17 17:38:05

- Jai Ganesh

- Replies: 0

College Quotes - III

1. Training is everything. The peach was once a bitter almond; cauliflower is nothing but cabbage with a college education. - Mark Twain

2. I had tried to go to college, and I didn't really fit in. I went to a real narrow-minded school where people gave me a lot of trouble, and I was hounded off the campus - I just looked different and acted different, so I left school. - Bruce Springsteen

3. In my family, there was one cardinal priority - education. College was not an option; it was mandatory. So even though we didn't have a lot of money, we made it work. I signed up for financial aid, Pell Grants, work study, anything I could. - Eva Longoria

4. I prefer ordinary girls - you know, college students, waitresses, that sort of thing. Most of the girls I go out with are just good friends. Just because I go out to the cinema with a girl, it doesn't mean we are dating. - Leonardo DiCaprio

5. All of my friends who have younger siblings who are going to college or high school - my number one piece of advice is: You should learn how to program. - Mark Zuckerberg

6. I got married when I was a first-year medical student and my husband was pursuing Nephrology in the same college. - Tamilisai Soundararajan

7. I've been composing music all my life and if I'd been clever enough at school I would like to have gone to music college. - Anthony Hopkins

8. America is the student who defies the odds to become the first in a family to go to college - the citizen who defies the cynics and goes out there and votes - the young person who comes out of the shadows to demand the right to dream. That's what America is about. - Barack Obama.

#71 Re: Jai Ganesh's Puzzles » 10 second questions » 2026-01-17 17:09:15

Hi,

#9830.

#72 Re: Jai Ganesh's Puzzles » Oral puzzles » 2026-01-17 16:55:59

Hi,

#6324.

#73 Re: Exercises » Compute the solution: » 2026-01-17 16:44:41

Hi,

2681.

#74 This is Cool » Mediterranean Sea » 2026-01-17 16:21:56

- Jai Ganesh

- Replies: 0

Mediterranean Sea

Gist

The Mediterranean Sea, which occupies an area of approximately 970,000 sq mi. (2,510,000 sq km), stretches from the Atlantic Ocean on the west to Asia on the east and separates Europe from Africa.

It's called the Mediterranean because the name comes from Latin words meaning "in the middle of the land" or "middle earth" (medius for middle + terra for land/earth), reflecting how ancient civilizations, especially the Romans, saw it as the center of their world, surrounded by continents. It's also a calque (loan translation) from the Greek term for "inland sea".

Calypso Deep is a moat that is the deepest point of the Mediterranean with a maximum depth of 5,269 meters. It is located in Greece, in the Ionian Sea, southwest of the city of Pylos and south of the small islands called Messinian Oinousses .

Summary

The Mediterranean Sea is an intercontinental sea situated between Europe, Asia, and Africa. It is surrounded by the Mediterranean basin and almost completely enclosed by land: on the east by the Levant in West Asia, on the north by Anatolia in West Asia and Southern Europe, and on the south by North Africa. To its west it is connected to the Atlantic Ocean via the Strait of Gibraltar that separates the Iberian Peninsula in Europe from Morocco in Africa by only 14 km (9 mi); additionally, it is connected to the Black Sea through the Bosporus strait that intersects Turkey in the northeast and the Red Sea via the Suez Canal in the southeast.

The Mediterranean Sea covers an area of about 2,500,000 {km}^{2} (970,000 sq mi), representing 0.7% of the global ocean surface; it includes fifteen marginal seas, including the Aegean, Adriatic, Tyrrhenian, and Marmara. Geological evidence indicates that around 5.9 million years ago, the Mediterranean was cut off from the Atlantic and was partly or completely desiccated over a period of some 600,000 years during the Messinian salinity crisis before being refilled by the Zanclean flood about 5.3 million years ago.

The history of the Mediterranean region is crucial to understanding the origins and development of many modern societies; it is sometimes described as an "incubator of Western civilization". and saw the emergence of some of the earliest and most advanced civilisations, including those of Egypt, Greece, and the Fertile Crescent. The Levant in the Eastern Mediterranean was among the first regions in the world to display permanent human habitation as early as 12,000 BC. The Mediterranean Sea was an important route for merchants, travellers, and migrants in antiquity, facilitating trade and cultural exchange between various peoples as well as colonisation and conquest. The Roman Empire maintained nautical hegemony over the sea for centuries and is the only state to have ever controlled all of its coast.

The Mediterranean Sea has an average depth of 1,500 m (4,900 ft) and the deepest recorded point is 5,109 ± 1 m (16,762 ± 3 ft) in the Calypso Deep in the Ionian Sea. It lies between latitudes 30° and 46° N and longitudes 6° W and 36° E. Its west–east length, from the Strait of Gibraltar to the Gulf of Alexandretta, on the southeastern coast of Turkey, is about 4,000 kilometres (2,500 mi). The north–south length varies greatly between different shorelines and whether only straight routes are considered. Also including longitudinal changes, the shortest shipping route between the multinational Gulf of Trieste and the Libyan coastline of the Gulf of Sidra is about 1,900 kilometres (1,200 mi). The water temperatures are mild in winter and warm in summer and give name to the Mediterranean climate type due to the majority of precipitation falling in the cooler months. Its southern and eastern coastlines are lined with hot deserts not far inland, but the immediate coastline on all sides of the Mediterranean tends to have strong maritime moderation.

The countries surrounding the Mediterranean and its marginal seas in clockwise order are Spain, France, Monaco, Italy, Slovenia, Croatia, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Montenegro, Albania, Greece, Turkey, Syria, Lebanon, Israel, Palestine (Gaza Strip), Egypt, Libya, Tunisia, Algeria, and Morocco; Cyprus and Malta are island countries in the sea. In addition, Northern Cyprus (de facto state) and two overseas territories of the United Kingdom (Akrotiri and Dhekelia, and Gibraltar) also have coastlines along the Mediterranean Sea. The drainage basin encompasses a large number of other countries, the Nile being the longest river ending in the Mediterranean Sea. The Mediterranean Sea encompasses a vast number of islands, some of them of volcanic origin. The two largest islands, in both area and population, are Sicily and Sardinia.

Details

Mediterranean Sea, an intercontinental sea that stretches from the Atlantic Ocean on the west to Asia on the east and separates Europe from Africa. It has often been called the incubator of Western civilization. This ancient “sea between the lands” occupies a deep, elongated, and almost landlocked irregular depression lying between latitudes 30° and 46° N and longitudes 5°50′ W and 36° E. Its west-east extent—from the Strait of Gibraltar between Spain and Morocco to the shores of the Gulf of Iskenderun on the southwestern coast of Turkey—is approximately 2,500 miles (4,000 km), and its average north-south extent, between Croatia’s southernmost shores and Libya, is about 500 miles (800 km). The Mediterranean Sea, including the Sea of Marmara, occupies an area of approximately 970,000 square miles (2,510,000 square km).

The western extremity of the Mediterranean Sea connects with the Atlantic Ocean by the narrow and shallow channel of the Strait of Gibraltar, which is roughly 8 miles (13 km) wide at its narrowest point; and the depth of the sill, or submarine ridge separating the Atlantic from the Alborán Sea, is about 1,050 feet (320 metres). To the northeast the Mediterranean is connected with the Black Sea through the Dardanelles (with a sill depth of 230 feet [70 metres]), the Sea of Marmara, and the strait of the Bosporus (sill depth of about 300 feet [90 metres]). To the southeast it is connected with the Red Sea by the Suez Canal.

Physiographic and geologic features:

Natural divisions

A submarine ridge between the island of Sicily and the African coast with a sill depth of about 1,200 feet (365 metres) divides the Mediterranean Sea into western and eastern parts. The western part in turn is subdivided into three principal submarine basins. The Alborán Basin is east of Gibraltar, between the coasts of Spain and Morocco. The Algerian (sometimes called the Algero-Provençal or Balearic) Basin, east of the Alborán Basin, is west of Sardinia and Corsica, extending from off the coast of Algeria to off the coast of France. These two basins together constitute the western basin. The Tyrrhenian Basin, that part of the Mediterranean known as the Tyrrhenian Sea, lies between Italy and the islands of Sardinia and Corsica.

The eastern Mediterranean is subdivided into two major basins. The Ionian Basin, in the area known as the Ionian Sea, lies to the south of Italy, Albania, and Greece, where the deepest sounding in the Mediterranean, about 16,000 feet (4,900 metres), has been recorded. A submarine ridge between the western end of Crete and Cyrenaica (Libya) separates the Ionian Basin from the Levantine Basin to the south of Anatolia (Turkey); and the island of Crete separates the Levantine Basin from the Aegean Sea, which comprises that part of the Mediterranean Sea north of Crete and bounded on the west and north by the coast of Greece and on the east by the coast of Turkey. The Aegean Sea contains the numerous islands of the Grecian archipelago. The Adriatic Sea, northwest of the main body of the eastern Mediterranean Sea, is bounded by Italy to the west and north and by Slovenia, Croatia, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Montenegro, and Albania to the east.

Geology

Until the 1960s the Mediterranean was thought to be the main existing remnant of the Tethys Sea, which formerly girdled the Eastern Hemisphere. Studies employing the theory of seafloor spreading that have been undertaken since the late 20th century, however, have suggested that the present Mediterranean seafloor is not part of the older (200 million years) Tethys floor. The structure and present form of this tectonically active basin and its bordering mountain system have been determined by the convergence and recession of the relatively stable continental plates of Eurasia and Africa during the past 44 million years. The interpretation of geologic data suggests that there are, at present, multiple main areas of collision between Africa and Eurasia, resulting in volcanism, mountain building, and land submergence.

Desiccation theory and bottom deposits

The study of seabed sediment cores drilled in 1970 and 1975 initially seemed to reinforce an earlier theory that about 6 million years ago the Mediterranean was a dry desert nearly 10,000 feet (3,000 metres) below the present sea level and covered with evaporite salts. High ridges at Gibraltar were assumed to have blocked the entry of Atlantic waters until about 5.5 million years ago, when these waters broke through to flood the Mediterranean. More-recent seismic and microfossil studies have suggested that the seafloor never was completely dry. Instead, about 5 million years ago the seafloor consisted of several basins of variable size and topography, with depths ranging from 650 to 5,000 feet (200 to 1,500 metres). Highly saline waters of greatly varying depth probably covered the bottom and deposited salts. Considerable uncertainty has remained regarding the chronology and character of sea-bottom salt formation, and evidence from subsequent seismic studies and core sampling has been subject to intense scientific debate.

Physiography

The Tyrrhenian Basin of the western Mediterranean has two exits into the eastern Mediterranean: the Strait of Sicily and the Strait of Messina, both of which have been of great strategic importance throughout Mediterranean history. The submarine relief of the Sicilian channel is rather complicated; the group of islands comprising Malta, Gozo, and Comino, all of which consist of limestone, stands on a submarine shelf that extends southward from Sicily.

The widest continental shelf is off Spain at the Ebro River delta, where it extends about 60 miles (95 km). Similarly, west of Marseille, France, the shelf widens at the Rhône River delta to 40 miles (65 km). The shelf is narrow along the French Riviera, the gradient of its slope increasing where cut by canyons and troughs. The narrow shelves continue off the Italian peninsula, generally with lower, more-gradual slopes. Along the coast at the base of the Atlas Mountains of North Africa, a narrow shelf stretches from the Strait of Gibraltar to the Gulf of Tunis with a slope marked by many troughlike indentations.

The coasts of the western Mediterranean, just as those of the eastern basin, have been subjected in recent geologic times to the uneven action of deposition and erosion. This action, together with the movements of the sea and the emergence and submergence of the land, resulted in a rich variety of types of coasts. The Italian peninsula underwent considerable uplift in post-Pliocene times (i.e., within the past 2.6 million years), as a result of which a strip of older rocks has been exposed on the Adriatic flank of the Apennines. The Italian Adriatic coast is typical of an emerged coast. The granite coast of northeastern Sardinia and the Dalmatian coast where the eroded land surface has sunk, producing elongated islands parallel to the coast, are typical submerged coasts. The deltas of the Rhône, Po, Ebro, and Nile rivers are good examples of coasts resulting from silt deposition.

The Sicilian straits scarcely exceed 1,500 feet (460 metres) in depth, so that there is essentially a shelf from Tunisia to Sicily separating the Mediterranean into two parts. South of the straits the shelf widens to as much as 170 miles (275 km) off the Gulf of Gabes (Qābis) on the eastern coast of Tunisia. The first mud appears on the approach to the Nile delta, and the shelf widens again to 70 miles (115 km) off Port Said, Egypt, at the entrance to the Suez Canal. Narrow shelves continue along most of the northern shore of the Mediterranean. An exception is the broad shelf extending for 300 miles (485 km) along the inner portion of the Adriatic Sea. Relatively deep water is found along much of the coasts of Croatia, Bosnia and Herzegovina, and Montenegro and along the southern Italian coast, in contrast to the gentle slopes of the Po River region.

The northern shores of the eastern Mediterranean are highly complex and, unlike the southern shores, have variable fold mountains that offered favourable sites for the development of the Mediterranean civilizations. The north coast of Africa bordering the eastern Mediterranean is low-lying and of monotonous uniformity except for the Cyrenaica highlands in Libya, which lie to the east of the Gulf of Sidra. The largest islands of the eastern Mediterranean are Crete and Cyprus, both of which are mountainous.

Hydrologic features and climate:

Hydrology

Mediterranean hydrodynamics are driven by three layers of water masses: a surface layer, an intermediate layer, and a deep layer that sinks to the bottom; a separate bottom layer is absent. Deepwater formation and exchange rates and the processes of heat and water exchange in the Mediterranean have provided useful models for studying the mechanisms of global climatic change.

The surface layer has a thickness varying from roughly 250 to 1,000 feet (75 to 300 metres). This variable thickness is determined in the western basin by the presence of a minimum temperature at its lower limit. In the eastern basin the temperature minimum generally is absent, and a layer of low-temperature decrease is found instead. The intermediate layer is infused with warm and saline water coming from the eastern Mediterranean and is characterized by temperature and salinity maxima at 1,300 feet (400 metres). This layer is situated at depths between 1,000 and 2,000 feet (300 and 600 metres). The deep layer—containing the great bulk of Mediterranean water—occupies the remaining zone between the intermediate layer and the bottom. In general, the water of this layer is homogeneous.

The Mediterranean Sea receives from the rivers that flow into it only about one-third of the amount of water that it loses by evaporation. In consequence, there is a continuous inflow of surface water from the Atlantic Ocean. After passing through the Strait of Gibraltar, the main body of the incoming surface water flows eastward along the north coast of Africa. This current is the most constant component of the circulation of the Mediterranean. It is most powerful in summer, when evaporation in the Mediterranean is at a maximum. This inflow of Atlantic water loses its strength as it proceeds eastward, but it is still recognizable as a surface movement in the Sicilian channel and even off the Levant coast. A small amount of water also enters the Mediterranean from the Black Sea as a surface current through the Bosporus, the Sea of Marmara, and the Dardanelles.

In summer, Mediterranean surface water becomes more saline through the intense evaporation, and, correspondingly, its density increases. It therefore sinks, and the excess of this denser bottom water emerges into the Atlantic Ocean over the shallow sill of the Strait of Gibraltar as a westward subsurface current below the inward current. The inflowing water extends from the surface down to 230 or 260 feet (70 or 80 metres). The Mediterranean has been metaphorically described as breathing—i.e., inhaling surface water from the Atlantic and exhaling deep water in a countercurrent below.

Surface circulation of the Mediterranean consists basically of a separate counterclockwise movement of the water in each of the two basins. Because of the complexity of the northern coastline and of the numerous islands, many small eddies and other local currents form essential parts of the general circulation. Tides, although significant in range only in the Gulf of Gabes and in the northern Adriatic, add to the complications of the currents in narrow channels such as the Strait of Messina.

International Waters

Historically, large seasonal variations in the Nile’s discharge influenced the hydrology, productivity, and fisheries of the southeastern part of the Mediterranean. The Nile’s inflow reduced the salinity of the coastal waters, which increased both their stratification and productivity. Construction of the Aswān High Dam (1970), however, stopped the seasonal fluctuation of the discharge of the Nile water into the Mediterranean. Salty water enters the Mediterranean to some degree from the Red Sea via the Suez Canal.

Temperature and water chemistry

The parallel of 40° N latitude runs through the middle of the western basin, whereas the corresponding latitude of the eastern basin is 34° N; this explains the higher surface temperature of the latter. The highest temperature of the Mediterranean is in the Gulf of Sidra, off the coast of Libya, where the mean temperature in August is about 88 °F (31 °C). This is followed by the Gulf of Iskenderun, with a mean temperature of about 86 °F (30 °C). The lowest surface temperatures are found in the extreme north of the Adriatic, where the mean temperature in February falls to 41 °F (5 °C) in the Gulf of Trieste. Ice occasionally forms there in the depth of winter. In the deep zone the temperature range is small—approximately 55.2 °F (12.9 °C) at 3,000 feet (900 metres) and 55.6 °F (13.1 °C) at 8,200 feet (2,500 metres)—and temperatures remain constant throughout the year.

The salinity of the Mediterranean is uniformly high throughout the basin. Surface waters average about 38 parts per thousand except in the extreme western parts, and the salinity can approach 40 parts per thousand in the eastern Mediterranean during the summer. Deepwater salinity is 38.4 parts per thousand or slightly less. As in all other seas and oceans, chlorides constitute more than half of the total ions present in Mediterranean water, and the proportions of all the principal salts in the water are constant.

Levels of dissolved oxygen vary with the origin of the different water masses. The surface layer down to 700 feet (210 metres) shows a high oxygen level throughout the Mediterranean. The intermediate layer formed by the sinking of the surface layer in the eastern basin has a high oxygen level where it is freshly formed in this basin, but, as it moves westward, it loses some of its oxygen content, the lowest values occurring in the Algerian Basin. The transition layer between the intermediate and the deep water has the lowest level of dissolved oxygen.

Climate

Earth; satellite imageThe Mediterranean Sea is mostly enclosed by southern Europe and northern Africa. It is linked to the Atlantic Ocean by the Strait of Gibraltar.

Airflow into the Mediterranean Sea is through gaps in the mountain ranges, except over the southern shores east of Tunisia. Strong winds funneled through the gaps lead to the high evaporation rates of summer and the seasonal water deficit of the sea. The mistral—a cold, dry northwesterly wind—passes through the Alps-Pyrenees gap and the lower Rhône valley; the strong northeasterly bora passes through the Trieste gap; and the cold easterly levanter and the westerly vendaval pass through the Strait of Gibraltar. Hot, dry southeasterly winds—known locally as the sirocco, ghibli (gibleh), or khamsin—frequently blow into the Mediterranean basin from the Sahara and the Arabian Peninsula as low-pressure centres traverse the sea in late winter and early spring. These winds reduce heat and moisture in the surface waters to a significant degree by evaporative cooling, and this colder, denser surface water sinks. Atmospheric conditions over the Mediterranean also increase the salinity of incoming Atlantic water because of the evaporation of surface waters.

Mediterranean climate is confined to coastal zones and is characterized by windy, mild, wet winters and relatively calm, hot, dry summers. Spring, however, is a transitional season and is changeable. Autumn is relatively short.

The amount and distribution of rainfall in Mediterranean localities is variable and unpredictable. Along the North African coast from Qābis (Gabès) in Tunisia to Egypt, more than 10 inches (250 mm) of rainfall per year is rare, whereas on the Dalmatian coast of Croatia there are places that receive 100 inches (2,500 mm). Maximum precipitation is found in mountainous coastal areas.

Economic aspects:

Biological resources

Plant nutrients such as phosphates, nitrates, and nitrites are scarce in the Mediterranean Sea. Just as in all other seas, these nutrients show seasonal fluctuations, generally with a rise in the spring, the phytoplankton blooming season. However, several factors account for the scarcity of nutrients in Mediterranean waters, the most important being that the Mediterranean receives most of its water from the surface water of the Atlantic Ocean. Despite low nutrient levels, the Mediterranean has a rich diversity of marine biota. Nearly one-third of its roughly 12,000 species are endemic.

The effective potential productivity in various regions of the Mediterranean can be measured by radioactive methods using carbon-14 dating to determine the amount of carbon produced in a given volume of water over a period of time. The lowest values are observed in the Levant and also in the Ionian Basin. The highest primary-production values in the Mediterranean Sea have been observed in springtime (March–May) off the Egyptian coast in areas under the influence of the outflow of the Nile.

Commercial fisheries are highly valuable in the nutrient-poor Mediterranean. There is great demand for fish, and total catches for consumption in Mediterranean countries—both from within and outside the region—constitute a significant portion of the total world catch. The high price of fresh fish in most Mediterranean countries has favoured the development of a large number of small-scale local fisheries, which take small catches in short trips. Though the boats used rarely exceed 70 feet (20 metres) in length, their numbers are sufficient to deplete the local stocks through overfishing.

The tendency to overexploitation is strengthened by the use of trawl nets with very small mesh size that retain the smallest individuals. Efforts to reduce the catch of undersized fish through controlling mesh size have not been successful, because equipment varies from country to country and compliance is difficult to monitor. The most recent trend has been to use drift nets up to 15 miles (24 km) long that extend 40 feet (12 metres) into the water. These nets kill many noncommercial species, including dolphins, whales, sea turtles, and the endangered Mediterranean monk seal.

The fishes of the Mediterranean are related to subtropical Atlantic species. Of the demersal (bottom-living) fishes, flounder, soles, turbot, whitings, congers, croakers, red mullet, gobies, gurnard, lizard fish, redfishes, sea bass, groupers, combers, sea bream, pandoras, and jacks and cartilaginous fishes such as sharks, rays, and skates are all caught by the trawlers. Among the demersal fishes, hake is one of the more commercially important in all countries bordering the Mediterranean Sea.