Math Is Fun Forum

You are not logged in.

- Topics: Active | Unanswered

- Index

- » This is Cool

- » Neuron

Pages: 1

#1 Yesterday 19:43:46

- Jai Ganesh

- Administrator

- Registered: 2005-06-28

- Posts: 53,068

Neuron

Neuron

Gist

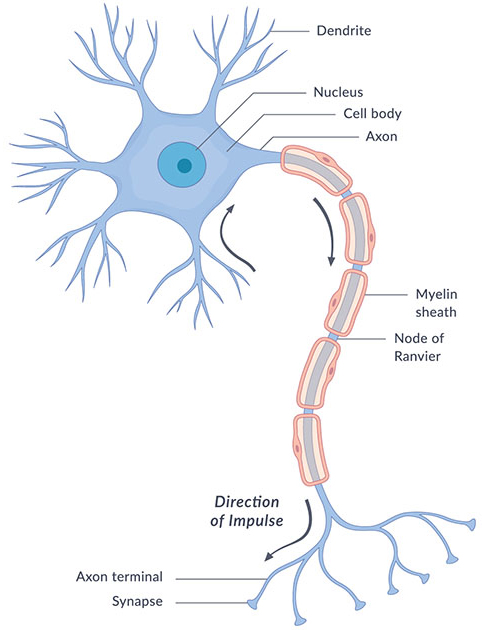

A neuron, or nerve cell, is the fundamental unit of the nervous system, specialized to transmit information via electrical and chemical signals, enabling functions from thinking and feeling to movement, and forms the basis of the brain and nerves throughout the body. Structurally, a neuron typically consists of a cell body (soma), dendrites that receive signals, and an axon that transmits signals to other cells.

The basic functions of neurons can be summarized into four main tasks: receiving signals, integrating these signals/generating signals and transmitting the signals to target cells and organs. These functions reflect in the microanatomy of the neuron.

Summary

A neuron (American English), neurone (British English), or nerve cell, is an excitable cell that fires electric signals called action potentials across a neural network in the nervous system, mainly in the central nervous system and help to receive and conduct impulses. Neurons communicate with other cells via synapses, which are specialized connections that commonly use minute amounts of chemical neurotransmitters to pass the electric signal from the presynaptic neuron to the target cell through the synaptic gap.

Neurons are the main components of nervous tissue in all animals except sponges and placozoans. Plants and fungi do not have nerve cells. Molecular evidence suggests that the ability to generate electric signals first appeared in evolution some 700 to 800 million years ago, during the Tonian period. Predecessors of neurons were the peptidergic secretory cells. They eventually gained new gene modules which enabled cells to create post-synaptic scaffolds and ion channels that generate fast electrical signals. The ability to generate electric signals was a key innovation in the evolution of the nervous system.

Neurons are typically classified into three types based on their function. Sensory neurons respond to stimuli such as touch, sound, or light that affect the cells of the sensory organs, and they send signals to the spinal cord and then to the sensorial area in the brain. Motor neurons receive signals from the brain and spinal cord to control everything from muscle contractions to glandular output. Interneurons connect neurons to other neurons within the same region of the brain or spinal cord. When multiple neurons are functionally connected together, they form what is called a neural circuit.

A neuron contains all the structures of other cells such as a nucleus, mitochondria, and Golgi bodies but has additional unique structures such as an axon, and dendrites. The soma or cell body, is a compact structure, and the axon and dendrites are filaments extruding from the soma. Dendrites typically branch profusely and extend a few hundred micrometers from the soma. The axon leaves the soma at a swelling called the axon hillock and travels for as far as 1 meter in humans or more in other species. It branches but usually maintains a constant diameter. At the farthest tip of the axon's branches are axon terminals, where the neuron can transmit a signal across the synapse to another cell. Neurons may lack dendrites or have no axons. The term neurite is used to describe either a dendrite or an axon, particularly when the cell is undifferentiated.

Most neurons receive signals via the dendrites and soma and send out signals down the axon. At the majority of synapses, signals cross from the axon of one neuron to the dendrite of another. However, synapses can connect an axon to another axon or a dendrite to another dendrite. The signaling process is partly electrical and partly chemical. Neurons are electrically excitable, due to the maintenance of voltage gradients across their membranes. If the voltage changes by a large enough amount over a short interval, the neuron generates an all-or-nothing electrochemical pulse called an action potential. This potential travels rapidly along the axon and activates synaptic connections as it reaches them. Synaptic signals may be excitatory or inhibitory, increasing or reducing the net voltage that reaches the soma.

In most cases, neurons are generated by neural stem cells during brain development and childhood. Neurogenesis largely ceases during adulthood in most areas of the brain.

Details

The nervous system consists of two main cell types, neurons and supporting glial cells. The neuron (or nerve cell) is the functional unit of both the central nervous system (CNS) and the peripheral nervous system (PNS). The basic functions of neurons can be summarized into four main tasks: receiving signals, integrating these signals/generating signals and transmitting the signals to target cells and organs. These functions reflect in the microanatomy of the neuron. As such, neurons typically consist of four main functional parts which include the:

* Receptive part (dendrites), which receive and conduct electrical signals toward the cell body

* Integrative part (usually equated with the cell body/soma), containing the nucleus and most of the cell's organelles, acting as the trophic center of the entire neuron. More importantly, it is here where inputs are processed and integrated to determine whether an electrical impulse (action potential) will be generated.

* Conductive part (axon), which conducts electrical impulses away from the cell body.

* Transmissive part (axon terminals), where axons communicate with other neurons or effectors (target structures which respond to nerve impulses)

Neurons are categorized into different types based on their unique morphologies and functions. This article will focus on the structure and physiology of a typical multipolar neuron, the primary neuronal type found in the CNS, and explore its parts and functions in greater detail.

Neurons: Structure and types:

Neuron structure

Description: Spherical or polygonal central component of a neuron

Function: Integration and signal processing, protein synthesis, metabolic activities

Components: Nucleus (DNA), cytoplasmic organelles (endoplasmic reticulum (smooth and rough), Golgi apparatus, microtubules, mitochondria, lysosomes), axon hillock

Axon hillock

Description: Specialized, cone-shaped region of the cell body which forms the initial segment of the axon

Function: Site for initiation of action potentials (with initial segment of axon)

Components:

- Devoid of large cytoplasmic organelles (Nissl bodies and Golgi apparatus),

- Contains high density of voltage-gated sodium channels

Dendrites

Description: Tree-like, short, tapering processes of varying shape

Function: Reception of synaptic signals and translation into electrical events

Components: Similar to the cell body, neurotransmitter receptors, dendritic shaft, dendritic spines

Axon (nerve fiber)

Description: Single long process arising from the axon hillock

Function: Conduction of electrical impulses away from the cell body

Components:

- Axolemma (cell membrane), axoplasm (cytoplasm), myelin sheath, myelin sheath gaps (nodes of Ranvier), terminal arborizations, terminal boutons, microtubules, intermediate filaments

- Devoid of endoplasmic reticulum and ribosomes

Cell body

The cell body of a neuron, also known as the soma, is typically located at the center of the dendritic tree in multipolar neurons. It is spherical or polygonal in shape and relatively small, making up one-tenth of the total cell volume.

The functionality of the neuron is highly dependent on its cell body as it houses the nucleus, which contains the genetic material (DNA) of the cell as well as various cytoplasmic organelles. These organelles include the endoplasmic reticulum (both smooth and rough), which clusters with free ribosomes to form what is known as chromatophilic substances ( Nissl bodies) and are involved in the protein synthesis of enzymes, receptors, ion channels and other structural components. Additionally, the cell body contains the Golgi apparatus and microtubules, involved in the packaging and transport of proteins; mitochondria, involved in energy production; and lysosomes involved in the waste management of the cell.

The axon hillock refers to an anatomically and functionally distinct area of the cell body which serves as the origin of the axon. It is cone-shaped and devoid of large cytoplasmic organelles such as chromatophilic substance (Nissl bodies) and Golgi apparatus. The axon hillock contains a high density of voltage-gated sodium channels, allowing it to serve as a critical site for determining whether or not the sum of all incoming signals warrants the propagation of an action potential. It also supports neuron polarity by separating the receptive/integrative parts from the conductive/transmissive parts, providing directionality in the flow of information from the dendrites to the cell body, axon and axon terminals.

The region of the axon laying between the axon hillock and the beginning of the myelin sheath is termed the initial segment. This is the actual site of action potential generation, although more recent research states that both the initial segment and axon hillock are capable of action potential generation.

Dendrites

Dendrites are tree-like processes extending from the cell body of the neuron and contain organelles similar to those in the cell body. The highly branched structure of dendrites provides an increased surface area for receiving information from other neurons at specialized areas of contact called synapses. Dendrites primarily consist of dendritic shafts, which serve as the main structural branches.

These are lined with numerous tiny protrusions called dendritic spines, which serve as sites for the initial processing of synaptic signals via membrane embedded neurotransmitter receptors; they translate the chemical messages received into electrical events, which travel down the dendrites. There are approximately ten trillion of these structures present across all dendrites of neurons in the human cerebral cortex (for 16-20 billion neurons), therefore they greatly increase the area available for synaptic events.

Axon

The axon of a neuron is also known as a nerve fiber. The membrane of an axon is known as the axolemma, while the cytoplasm is also referred to as axoplasm. Bundles of axons in the CNS form a tract, while in the PNS, they are referred to as fascicles (which, when bound together with connective tissue, form nerves). Axons originate from the axon hillock and conduct electrical impulses, in the form of action potentials, away from the cell body through a process of sequential depolarization and repolarization. Unlike dendrites that form a complex network with many tapering branches, the axon of a neuron is usually a single, long process that can extend for a considerable distance before it branches and terminates. The length of axons varies and can sometimes exceed a meter, such as in some peripheral nerves like the sciatic nerve, which extends from the spinal cord to the feet.

Axons typically terminate as fine branches called terminal arborizations; each of which is capped with a terminal bouton. These specialized structures contain synaptic vesicles that store neurotransmitters to be released into the synaptic cleft (a small gap at a synapse between neurons where nerve impulses are transmitted by a neurotransmitter) when an action potential reaches the axon terminal.

Axons can be enveloped in an insulating layer of lipids and proteins called the myelin sheath. This sheath protects the axon and prevents the loss of electrical charge (ions) during the transmission of action potentials along the neuron, increasing the speed of impulse transmission. The myelin sheath is formed by specific types of glial cells, namely oligodendrocytes in the CNS and Schwann cells (neurolemmocytes) in the PNS. The myelination of PNS axons involves many Schwann cells, each of which participates in the formation of the myelin sheath of a single axon, by wrapping around it multiple times. Not all axons are covered by myelin. In the PNS, multiple nonmyelinated axons can go through a single Schwann cell, without myelin sheath production. In contrast, an oligodendrocyte can myelinate multiple axons in the CNS, due to its arm-like processes twisting around them.

The outermost nucleated cytoplasmic layer of Schwann cells overlying the myelin sheath is called the neurolemma. This structural characteristic aids in the regeneration of damaged peripheral axons when the corresponding cell body remains intact. In contrast, CNS neurons, which lack a neurolemma, exhibit limited regenerative capacity.

Nerve fibers are classified into groups, based on their myelination; group A neurons are heavily myelinated, group B are moderately myelinated, and group C are nonmyelinated. Along myelinated axons, evenly distributed gaps known as myelin sheath gaps (commonly referred to as nodes of Ranvier) allow electrical impulses to jump from node to node. This propagation pattern is referred to as saltatory conduction. Myelin sheath gapsare more numerous in axons of the PNS compared to those of the CNS.

Since axons lack endoplasmic reticulum and ribosomes, proteins and organelles needed for its growth are synthesized in the cell body and then transported to the axon via axonal transport. This is facilitated by microtubules and intermediate filaments that provide cytoskeletal "tracks" for transportation. The microtubule arrangements overlap, providing routes for simultaneous transport of different materials to and from the cell body.

Additional Information

Neurons (also called neurones or nerve cells) are the fundamental units of the brain and nervous system, the cells responsible for receiving sensory input from the external world, for sending motor commands to our muscles, and for transforming and relaying the electrical signals at every step in between. More than that, their interactions define who we are as people. Having said that, our roughly 100 billion neurons do interact closely with other cell types, broadly classified as glia (these may actually outnumber neurons, although it’s not really known).

The creation of new neurons in the brain is called neurogenesis, and this can happen even in adults.

What does a neuron look like?

A useful analogy is to think of a neuron as a tree. A neuron has three main parts: dendrites, an axon, and a cell body or soma (see image below), which can be represented as the branches, roots and trunk of a tree, respectively. A dendrite (tree branch) is where a neuron receives input from other cells. Dendrites branch as they move towards their tips, just like tree branches do, and they even have leaf-like structures on them called spines.

The axon (tree roots) is the output structure of the neuron; when a neuron wants to talk to another neuron, it sends an electrical message called an action potential throughout the entire axon. The soma (tree trunk) is where the nucleus lies, where the neuron’s DNA is housed, and where proteins are made to be transported throughout the axon and dendrites.

There are different types of neurons, both in the brain and the spinal cord. They are generally divided according to where they orginate, where they project to and which neurotransmitters they use.

Concepts and definitions

Axon – The long, thin structure in which action potentials are generated; the transmitting part of the neuron. After initiation, action potentials travel down axons to cause release of neurotransmitter.

Dendrite – The receiving part of the neuron. Dendrites receive synaptic inputs from axons, with the sum total of dendritic inputs determining whether the neuron will fire an action potential.

Spine – The small protrusions found on dendrites that are, for many synapses, the postsynaptic contact site.

Action potential – Brief electrical event typically generated in the axon that signals the neuron as 'active'. An action potential travels the length of the axon and causes release of neurotransmitter into the synapse. The action potential and consequent transmitter release allow the neuron to communicate with other neurons.

It appears to me that if one wants to make progress in mathematics, one should study the masters and not the pupils. - Niels Henrik Abel.

Nothing is better than reading and gaining more and more knowledge - Stephen William Hawking.

Online

Pages: 1

- Index

- » This is Cool

- » Neuron