Math Is Fun Forum

You are not logged in.

- Topics: Active | Unanswered

#2676 2026-01-20 19:31:10

- Jai Ganesh

- Administrator

- Registered: 2005-06-28

- Posts: 52,924

Re: Miscellany

2476) Fractional Distillation

Gist

Fractional distillation is the most common form of separation technology used in petroleum refineries, petrochemical and chemical plants, natural gas processing and cryogenic air separation plants. In most cases, the distillation is operated at a continuous steady state.

Fractional distillation is a method to separate a liquid mixture into its parts (fractions) by heating it, relying on the components' different boiling points, especially when those boiling points are close (less than 25°C apart). It uses a fractionating column with obstacles to create multiple cycles of vaporization and condensation, allowing for a purer separation of components than simple distillation.

Summary

The various components of crude oil have different sizes, weights and boiling temperatures; so, the first step is to separate these components. Because they have different boiling temperatures, they can be separated easily by a process called fractional distillation. The steps of fractional distillation are as follows:

* You heat the mixture of two or more substances (liquids) with different boiling points to a high temperature. Heating is usually done with high pressure steam to temperatures of about 1112 degrees Fahrenheit / 600 degrees Celsius.

* The mixture boils, forming vapor (gases); most substances go into the vapor phase.

* The vapor enters the bottom of a long column (fractional distillation column) that is filled with trays or plates. The trays have many holes or bubble caps (like a loosened cap on a soda bottle) in them to allow the vapor to pass through. They increase the contact time between the vapor and the liquids in the column and help to collect liquids that form at various heights in the column. There is a temperature difference across the column (hot at the bottom, cool at the top).

* The vapor rises in the column.

* As the vapor rises through the trays in the column, it cools.

* When a substance in the vapor reaches a height where the temperature of the column is equal to that substance's boiling point, it will condense to form a liquid. (The substance with the lowest boiling point will condense at the highest point in the column; substances with higher boiling points will condense lower in the column.).

* The trays collect the various liquid fractions.

* The collected liquid fractions may pass to condensers, which cool them further, and then go to storage tanks, or they may go to other areas for further chemical processing.

Fractional distillation is useful for separating a mixture of substances with narrow differences in boiling points, and is the most important step in the refining process.

Very few of the components come out of the fractional distillation column ready for market. Many of them must be chemically processed to make other fractions. For example, only 40% of distilled crude oil is gasoline; however, gasoline is one of the major products made by oil companies. Rather than continually distilling large quantities of crude oil, oil companies chemically process some other fractions from the distillation column to make gasoline; this processing increases the yield of gasoline from each barrel of crude oil.

Details

Fractional distillation is the most common form of separation technology used in petroleum refineries, petrochemical and chemical plants, natural gas processing and cryogenic air separation plants. In most cases, the distillation is operated at a continuous steady state. New feed is always being added to the distillation column and products are always being removed. Unless the process is disturbed due to changes in feed, heat, ambient temperature, or condensing, the amount of feed being added and the amount of product being removed are normally equal. This is known as continuous, steady-state fractional distillation.

Industrial distillation is typically performed in large, vertical cylindrical columns known as "distillation or fractionation towers" or "distillation columns" with diameters ranging from about 0.65 to 6 meters (2 to 20 ft) and heights ranging from about 6 to 60 meters (20 to 197 ft) or more. The distillation towers have liquid outlets at intervals up the column which allow for the withdrawal of different fractions or products having different boiling points or boiling ranges. By increasing the temperature of the product inside the columns, the different products are separated. The "lightest" products (those with the lowest boiling point) exit from the top of the columns and the "heaviest" products (those with the highest boiling point) exit from the bottom of the column.

For example, fractional distillation is used in oil refineries to separate crude oil into useful substances (or fractions) having different hydrocarbons of different boiling points. The crude oil fractions with higher boiling points:

* have more carbon atoms

* have higher molecular weights

* are less branched-chain alkanes

* are darker in color

* are more viscous

* are more difficult to ignite and to burn

Large-scale industrial towers use reflux to achieve a more complete separation of products. Reflux refers to the portion of the condensed overhead liquid product from a distillation or fractionation tower that is returned to the upper part of the tower as shown in the schematic diagram of a typical, large-scale industrial distillation tower. Inside the tower, the reflux liquid flowing downwards provides the cooling needed to condense the vapors flowing upwards, thereby increasing the effectiveness of the distillation tower. The more reflux is provided for a given number of theoretical plates, the better the tower's separation of lower boiling materials from higher boiling materials. Alternatively, the more reflux provided for a given desired separation, the fewer theoretical plates are required.

Crude oil is separated into fractions by fractional distillation. The fractions at the top of the fractionating column have lower boiling points than the fractions at the bottom. All of the fractions are processed further in other refining units.

Fractional distillation is also used in air separation, producing liquid oxygen, liquid nitrogen, and highly concentrated argon. Distillation of chlorosilanes also enable the production of high-purity silicon for use as a semiconductor.

In industrial uses, sometimes a packing material is used in the column instead of trays, especially when low-pressure drops across the column are required, as when operating under vacuum. This packing material can either be random dumped packing (1–3 in (25–76 mm) wide) such as Raschig rings or structured sheet metal. Typical manufacturers are Koch, Sulzer, and other companies. Liquids tend to wet the surface of the packing and the vapors pass across this wetted surface, where mass transfer takes place. Unlike conventional tray distillation in which every tray represents a separate point of vapor liquid equilibrium the vapor-liquid equilibrium curve in a packed column is continuous. However, when modeling packed columns it is useful to compute several "theoretical plates" to denote the separation efficiency of the packed column concerning more traditional trays. Differently shaped packings have different surface areas and porosity. Both of these factors affect packing performance.

Design and operation of a distillation column depends on the feed and desired products. Given a simple, binary component feed, analytical methods such as the McCabe–Thiele method or the Fenske equation can be used. For a multi-component feed, simulation models are used both for design and operation.

Moreover, the efficiencies of the vapor-liquid contact devices (referred to as plates or trays) used in distillation columns are typically lower than that of a theoretical 100% efficient equilibrium stage. Hence, a distillation column needs more plates than the number of theoretical vapor-liquid equilibrium stages.

Reflux refers to the portion of the condensed overhead product that is returned to the tower. The reflux flowing downwards provides the cooling required for condensing the vapors flowing upwards. The reflux ratio, which is the ratio of the (internal) reflux to the overhead product, is conversely related to the theoretical number of stages required for efficient separation of the distillation products. Fractional distillation towers or columns are designed to achieve the required separation efficiently. The design of fractionation columns is normally made in two steps; a process design, followed by a mechanical design. The purpose of the process design is to calculate the number of required theoretical stages and stream flows including the reflux ratio, heat reflux, and other heat duties. The purpose of the mechanical design, on the other hand, is to select the tower internals, column diameter, and height. In most cases, the mechanical design of fractionation towers is not straightforward. For the efficient selection of tower internals and the accurate calculation of column height and diameter, many factors must be taken into account. Some of the factors involved in design calculations include feed load size and properties and the type of distillation column used.

The two major types of distillation columns used are tray and packing columns. Packing columns are normally used for smaller towers and loads that are corrosive or temperature-sensitive or for vacuum service where pressure drop is important. Tray columns, on the other hand, are used for larger columns with high liquid loads. They first appeared on the scene in the 1820s. In most oil refinery operations, tray columns are mainly used for the separation of petroleum fractions at different stages of oil refining.

In the oil refining industry, the design and operation of fractionation towers is still largely accomplished on an empirical basis. The calculations involved in the design of petroleum fractionation columns require in the usual practice the use of numerable charts, tables, and complex empirical equations. In recent years, however, a considerable amount of work has been done to develop efficient and reliable computer-aided design procedures for fractional distillation.

Additional Information

The inside of a fractional distilling column has sets of perforated trays. Each perforation is fitted with a bubble cap. Very hot, vaporized crude oil is pumped into the bottom of the column and rises up through the perforations. The bubble cap forces the oil vapor to bubble through liquid on the tray. This causes the vapor to cool as it flows upward and to condense into liquids. Excess liquid overflows through a pipe called a downcomer to the tray below. At various levels in the column, liquid is drawn off. The heavier products, such as straight-run heavy gas oil, are taken from the bottom part of the column and the lighter products, such as straight-run gasoline, are taken from the top. Straight-run natural gas comes out the top, and straight-run residuum comes out the bottom.

It appears to me that if one wants to make progress in mathematics, one should study the masters and not the pupils. - Niels Henrik Abel.

Nothing is better than reading and gaining more and more knowledge - Stephen William Hawking.

Offline

#2677 2026-01-21 16:44:30

- Jai Ganesh

- Administrator

- Registered: 2005-06-28

- Posts: 52,924

Re: Miscellany

2476) The Alps

The Alps

Gist

The Alps are Europe's highest and most extensive mountain range, forming a crescent across eight countries (France, Switzerland, Italy, Austria, Germany, Slovenia, Liechtenstein, Monaco), famous for Mont Blanc, Matterhorn, stunning scenery, skiing, biodiversity, and unique climate zones, originating from tectonic plate collision and providing vital water sources for Europe.

Which countries are in the Alps?

They stretch across eight countries: France, Switzerland, Italy, Monaco, Liechtenstein, Austria, Germany and Slovenia. The mountains were formed millions of years ago as two giant tectonic plates collided, creating some of the highest mountains in Europe, like the Matterhorn, Mont Blanc, and the Eiger.

Summary

The Alps are some of the highest and most extensive mountain ranges in Europe, stretching approximately 1,200 km (750 mi) across eight Alpine countries (from west to east): Monaco, France, Switzerland, Italy, Liechtenstein, Germany, Austria, Slovenia, and Hungary.

The Alpine arch extends from Nice on the western Mediterranean to Trieste on the Adriatic and Vienna at the beginning of the Pannonian Basin. The mountains were formed over tens of millions of years as the African and Eurasian tectonic plates collided. Extreme shortening caused by the event resulted in marine sedimentary rocks rising by thrusting and folding into high mountain peaks such as Mont Blanc and the Matterhorn.

Mont Blanc spans the French–Italian border, and at 4,809 m (15,778 ft) is the highest mountain in the Alps. The Alpine region area contains 82 peaks higher than 4,000 m (13,000 ft).

The altitude and size of the range affect the climate in Europe; in the mountains, precipitation levels vary greatly and climatic conditions consist of distinct zones. Wildlife such as ibex live in the higher peaks to elevations of 3,400 m (11,155 ft), and plants such as edelweiss grow in rocky areas in lower elevations as well as in higher elevations.

Evidence of human habitation in the Alps goes back to the Palaeolithic era. A mummified man ("Ötzi"), determined to be 5,000 years old, was discovered on a glacier at the Austrian–Italian border in 1991.

By the 6th century BC, the Celtic La Tène culture was well established. Hannibal notably crossed the Alps with a herd of elephants, and the Romans had settlements in the region. In 1800, Napoleon crossed one of the mountain passes with an army of 40,000. The 18th and 19th centuries saw an influx of naturalists, writers, and artists, in particular, the Romanticists, followed by the Golden Age of Alpinism as mountaineers began to ascend the peaks of the Alps.

The Alpine region has a strong cultural identity. Traditional practices such as farming, cheese making, and woodworking still thrive in Alpine villages. However, the tourist industry began to grow early in the 20th century and expanded significantly after World War II, eventually becoming the dominant industry by the end of the century.

The Winter Olympic Games have been hosted in the Swiss, French, Italian, Austrian and German Alps. As of 2010, the region is home to 14 million people and has 120 million annual visitors.

Details

Alps, a small segment of a discontinuous mountain chain that stretches from the Atlas Mountains of North Africa across southern Europe and Asia to beyond the Himalayas. The Alps extend north from the subtropical Mediterranean coast near Nice, France, to Lake Geneva before trending east-northeast to Vienna (at the Vienna Woods). There they touch the Danube River and meld with the adjacent plain. The Alps form part of France, Italy, Switzerland, Germany, Austria, Slovenia, Croatia, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Montenegro, Serbia, and Albania. Only Switzerland and Austria can be considered true Alpine countries, however. Some 750 miles (1,200 kilometres) long and more than 125 miles wide at their broadest point between Garmisch-Partenkirchen, Germany, and Verona, Italy, the Alps cover more than 80,000 square miles (207,000 square kilometres). They are the most prominent of western Europe’s physiographic regions.

Though they are not as high and extensive as other mountain systems uplifted during the Paleogene and Neogene periods (i.e., about 65 million to 2.6 million years ago)—such as the Himalayas and the Andes and Rocky mountains—they are responsible for major geographic phenomena. The Alpine crests isolate one European region from another and are the source of many of Europe’s major rivers, such as the Rhône, Rhine, Po, and numerous tributaries of the Danube. Thus, waters from the Alps ultimately reach the North, Mediterranean, Adriatic, and Black seas. Because of their arclike shape, the Alps separate the marine west-coast climates of Europe from the Mediterranean areas of France, Italy, and the Balkan region. Moreover, they create their own unique climate based on both the local differences in elevation and relief and the location of the mountains in relation to the frontal systems that cross Europe from west to east. Apart from tropical conditions, most of the other climates found on the Earth may be identified somewhere in the Alps, and contrasts are sharp.

A distinctive Alpine pastoral economy that evolved through the centuries has been modified since the 19th century by industry based on indigenous raw materials, such as the industries in the Mur and Mürz valleys of southern Austria that used iron ore from deposits near Eisenerz. Hydroelectric power development at the end of the 19th and beginning of the 20th centuries, often involving many different watersheds, led to the establishment in the lower valleys of electricity-dependent industries, manufacturing such products as aluminum, chemicals, and specialty steels. Tourism, which began in the 19th century in a modest way, became, after World War II, a mass phenomenon. Thus, the Alps are a summer and winter playground for millions of European urban dwellers and annually attract tourists from around the world. Because of this enormous human impact on a fragile physical and ecological environment, the Alps are likely the most threatened mountain system in the world.

Physical features:

Geology

The Alps emerged during the Alpine orogeny, an event that began about 65 million years ago as the Mesozoic Era was drawing to a close. A broad outline helps to clarify the main episodes of a complicated process. At the end of the Paleozoic Era, about 250 million years ago, eroded Hercynian mountains, similar to the present Massif Central in France and Bohemian Massif embracing parts of Germany, Austria, Poland, and the Czech Republic, stood where the Alps are now located. A large landmass, formed of crystalline rocks and known as Tyrrhenia, occupied what is today the western Mediterranean basin, whereas much of the rest of Europe was inundated by a vast sea. During the Mesozoic (about 250 million to 65 million years ago) Tyrrhenia was slowly leveled by the forces of erosion. The eroded materials were carried southward by river action and deposited at the bottom of a vast ocean known as the Tethys Sea, where they were slowly transformed into horizontal layers of rock composed of limestone, clay, shale, and sandstone.

About 44 million years ago, relentless and powerful pressures from the south first formed the Pyrenees and then the Alps, as the deep layers of rock that had settled into the Tethys Sea were folded around and against the crystalline bedrock and raised with the bedrock to heights approaching the present-day Himalayas. These tectonic movements lasted until 9 million years ago. Tyrrhenia sank at the beginning of the Quaternary Period, about 2.6 million years ago, but remnants of its mass, such as the rugged Estéral region west of Cannes, are still found in the western Mediterranean. Throughout the Quaternary Period, erosive forces gnawed steadily at the enormous block of newly folded and upthrust mountains, forming the general outlines of the present-day landscape.

The landscape was further modeled during the Quaternary by Alpine glaciation and by expanding ice tongues, some reaching depths of nearly 1 mile (1.6 kilometres), that filled in the valleys and overflowed onto the plains. Amphitheatre-like cirques, arête ridges, and majestic peaks such as the Matterhorn and Grossglockner were shaped from the mountaintops; the valleys were widened and deepened into general U-shapes, and immense waterfalls, like the Staubbach and Trümmelbach falls in the Lauterbrunnen Valley of the Bernese Alps, poured forth from hanging valleys hundreds of feet above the main valley floors; elongated lakes of great depth such as Lake Annecy in France, Lake Constance, bordering Switzerland, Germany, and Austria, and the lakes of the Salzkammergut in Austria filled in many of the ice-scoured valleys; and enormous quantities of sands and gravels were deposited by the melting glaciers, and landslides—following the melting of much of the ice—filled in sections of the valley floors. The hills east of Sierre in the Rhône valley are an example of this last phenomenon, and they mark the French–German language divide in this area.

When the ice left the main valleys, there was renewed river downcutting, both in the lateral and transverse valleys. The river valleys have been eroded to relatively low elevations that are well below those of the surrounding mountains. Thus, Aosta, Italy, in the Pennine Alps, and Sierre, Switzerland, look up to peaks that tower a mile and a half above them. In the valley of the Arve River near Mont Blanc, the difference in relief is more than 13,100 feet.

Glaciation therefore modified what otherwise would have been a harsher physical environment: the climate was much milder in the valleys than on the surrounding heights, settlement could be established deeper into the mountains, communication was facilitated, and soils were inherently more fertile because of morainic deposits. Vigorous glacial erosion continues in modern times. Many hundreds of square miles of Alpine glaciers, such as those in the Ortles and Adamello ranges and such deep-valley glaciers as the Aletsch Glacier near Brig, Switzerland, are still found in the Alps. The summer runoff from these ice masses is instrumental in filling the deep reservoirs used to generate hydroelectricity.

Physiography

The Alps present a great variety of elevations and shapes, ranging from the folded sediments forming the low-lying pre-Alps that border the main range everywhere except in northwestern Italy to the crystalline massifs of the inner Alps that include the Belledonne and Mont Blanc in France, the Aare and Gotthard in Switzerland, and the Tauern in Austria. From the Mediterranean to Vienna, the Alps are divided into Western, Central, and Eastern segments, each of which consists of several distinct ranges.

The Western Alps trend north from the coast through southeastern France and northwestern Italy to Lake Geneva and the Rhône valley in Switzerland. Their forms include the low-lying arid limestones of the Maritime Alps near the Mediterranean, the deep cleft of the Verdon Canyon in France, the crystalline peaks of the Mercantour Massif, and the glacier-covered dome of Mont Blanc, which at 15,771 feet (4,807 metres) is the highest peak in the Alps. Rivers from these ranges flow west into the Rhône and east into the Po.

The Central Alps occupy an area from the Great St. Bernard Pass east of Mont Blanc on the Swiss-Italian border to the region of the Splügen Pass north of Lake Como. Within this territory are such distinctive peaks as the Dufourspitze, Weisshorn, Matterhorn, and Finsteraarhorn, all 14,000 feet high. In addition, the great glacial lakes—Como and Maggiore in the south, part of the drainage system of the Po; and Thun, Brienz, and Lucerne (Vierwaldstättersee) in the north—fall within this zone.

The Eastern Alps, consisting in part of the Rätische range in Switzerland, the Dolomite Alps in Italy, the Bavarian Alps of southern Germany and western Austria, the Tauern Mountains in Austria, the Julian Alps in northeastern Italy and northern Slovenia, and the Dinaric Alps along the western edge of the Balkan Peninsula, generally have a northerly and southeasterly drainage pattern. The Inn, Lech, and Isar rivers in Germany and the Salzach and Enns in Austria flow into the Danube north of the Alps, while the Mur and Drau (Austria) and Sava (Balkan region) rivers discharge into the Danube east and southeast of the Alps. Within the Eastern Alps in Italy, Lake Garda drains into the Po, whereas the Adige, Piave, Tagliamento, and Isonzo pour into the Gulf of Venice.

Differences in relief within the Alps are considerable. The highest mountains, composed of autochthonous crystalline rocks, are found in the west in the Mont Blanc massif and also in the massif centring on Finsteraarhorn (14,022 feet) that divides the cantons of Valais and Bern. Other high chains include the crystalline rocks of the Mount Blanche nappe—which includes the Weisshorn (14,780 feet)—and the nappe of Monte Rosa Massif, sections of which mark the frontier between Switzerland and Italy. Farther to the east, Bernina Peak is the last of the giants over 13,120 feet (4,000 metres). In Austria the highest peak, the Grossglockner, reaches only 12,460 feet; Germany’s highest point, the Zugspitze in the Bavarian Alps, only 9,718 feet; and the highest point of Slovenia and the Julian Alps, Triglav, only 9,396 feet. Some of the lowest areas within the Western Alps are found at the delta of the Rhône River where the river enters Lake Geneva, 1,220 feet. In the valleys of the Eastern Alps north of Venice, elevations of only about 300 feet are common.

Climate of the Alps

The location of the Alps, as well as the great variations in their elevations and exposure, give rise to extreme differences in climate, not only among separate ranges but also within a particular range itself. Because of their central location in Europe, the Alps are affected by four main climatic influences: from the west flows the relatively mild, moist air of the Atlantic; cool or cold polar air descends from northern Europe; continental air masses, cold and dry in winter and hot in summer, dominate in the east; and, to the south, warm Mediterranean air flows northward. Daily weather is influenced by the location and passage of cyclonic storms and the direction of the accompanying winds as they pass over the mountains.

Temperature extremes and annual precipitation are related to the physiography of the Alps. The valley bottoms clearly stand out because generally they are warmer and drier than the surrounding heights. In winter nearly all precipitation above 5,000 feet is in the form of snow, and depths from 10 to 33 feet or more are common. Snow cover lasts from approximately mid-November to the end of May at the 6,600-foot level, blocking the high mountain passes; nevertheless, relatively snowless winters can occur. Mean January temperatures on the valley floors range from 23 to 39 °F (−5 to 4 °C) to as high as 46 °F (8 °C) in the mountains bordering the Mediterranean, whereas mean July temperatures range between 59 and 75 °F (15 and 24 °C). Temperature inversions are frequent, especially during autumn and winter, and the valleys often fill with fog and stagnant air for days at a time. At those times the levels above 3,300 feet can be warmer and sunnier than the low-lying valley bottoms. Winds can play a prominent role in daily weather and microclimatic conditions.

A foehn wind can last from two to three days and blows either south–north or north–south, depending on the tracking of cyclonic storms. The air mass of such a wind is cooled adiabatically as it passes upward to the mountain crests, which precipitates either rain or snow and retards the rate of cooling. When this drier air descends on the lee side, it is adiabatically warmed by compression at a constant rate and therefore has a higher temperature at the same altitude than when it began its upward flow. Snow in the affected areas disappears rapidly.

Avalanches, one of the great destructive forces of nature, are an ever-present danger during the period from late November to early June. Most follow well-defined paths, but much of the fear of avalanches is related to the difficulty of predicting where and when they will strike. Avalanches are a greater threat to human life and property in the Alps than in other mountain ranges because of the region’s relatively high population density and the tens of millions of tourists who visit each year. The development of ski resorts also has depleted many forests, which serve as natural barriers against avalanches.

Additional Information:

Geography:

The Alps are the highest and most extensive mountain range system that lie in south-central Europe. The mountain range stretches approximately 750 miles (1,200 kilometers) in a crescent shape across eight Alpine countries: France, Switzerland, Monaco, Italy, Liechtenstein, Austria, Germany, and Slovenia.

Ecology:

The Alps are an interzonal mountain system (Orobiome), or a “transition area” between Central and Mediterranean Europe. The Alps have high habitat diversity, with 200 habitats classified throughout the mountain range. This mountain range is home to a high level of biodiversity.

According to the World Wildlife Fund (WWF), there are over 4,500 species of plants, 200 bird species, 21 amphibian species, 15 reptile species, and 80 mammal species. Many of these species have made adaptations to the harsh cold conditions and high altitudes.

None of the 80 mammal species found in the Alps are “strictly” endemic, meaning they occur in the Alps and nowhere else in the world. Some of the larger carnivore species found in the Alps include the Eurasian lynx, the wolf, and the brown bear, and herbivores include the Alpine ibex, the chamois. These populations have been reduced in size or fragmented into small groups. There are also numerous rodent species found in the Alps, such as voles and marmots.

There are about 200 breeding bird species, as well as an equal number of migratory species, in the Alps. The largest bird species found in the Alps are the golden eagle and the bearded vulture. The alpine chough is the most common bird found in the region.

Of the 21 total species of amphibians, only one is endemic, Salamandra lanzai. There are fifteen reptile species present, including adders and vipers.

According to WWF, the Alps are one of the regions with the richest flora and fauna in Europe, second only to the Mediterranean. There are about 4,500 species of vascular plants, 800 species of mosses, 300 liverworts, 2500 lichens and more than 5000 fungi found in the Alps. About 8 percent of the vascular species are endemic. The variety of habitats in the Alps helps to promote the uniqueness of Alpine flora, along with the harsh environmental conditions that drive species to change and adapt.

Highest peak:

Mont Blanc is the highest peak at 15,776 feet (4,808 m). It is the second-highest and second most prominent mountain in Europe and the eleventh most prominent mountain summit in the world. The Mont Blanc massif spans across France, Italy, and Switzerland, while the summit itself lies on the border between France and Italy. There are about a hundred peaks higher than 13,000 ft (4,000 m) in the Alpine region.

Rivers:

The Alps provide lowland Europe with drinking water, irrigation, and hydroelectric power. Although the area is only about 11% of the surface area of Europe, the Alps provide up to 90% of water to lowland Europe. Major European rivers flow from the Alps, including the Rhine, the Rhône, the Inn, and the Po.

Glaciers:

The major glacierized areas in the Alps are situated along the crest of the mountain chain, with the largest glaciers often found at the highest elevations. There are smaller glaciers scattered throughout the Alps.

The Swiss Alps is known for glaciers, containing around 1,800 glaciers. The region’s glaciers include the longest glacier in the Alps: the Aletsch Glacier.

Additional Facts:

* At over 12 miles long and about a half-mile thick, the famous Aletsch valley glacier is the longest in the Alps, but due to climate change, the Aletsch is shrinking and predicted to completely melt by the end of this century.

* The Alps are Europe’s highest and most extensive mountain range.

* Mont Blanc is the highest mountain in the Alps, spanning 3 countries. Its granite ramparts distinguish it from other peaks. Mont Blanc’s ranges rose straight from the deep and are still rising, a phenomenon caused by glacial movement.

* The limestone Dolomites in Italy are half as high as Mont Blanc and were created as Africa’s collision with Europe pushed together an ancient tropical seafloor with the ancient skeletons of marine organisms into the sky.

* Humans have been living in the Alps since Paleolithic times, about 60,000 to 50,000 years ago. The Alpine region continues to have a strong cultural identity and its traditional culture of farming, cheesemaking, and woodworking still exists in Alpine villages. However, the tourism industry has been growing since the 20th century. While the region is home to 14 million people, it has 120 million annual visitors.

It appears to me that if one wants to make progress in mathematics, one should study the masters and not the pupils. - Niels Henrik Abel.

Nothing is better than reading and gaining more and more knowledge - Stephen William Hawking.

Offline

#2678 Yesterday 22:59:01

- Jai Ganesh

- Administrator

- Registered: 2005-06-28

- Posts: 52,924

Re: Miscellany

2477) Photosysthesis

Gist

Photosynthesis is the vital process where plants, algae, and some bacteria use sunlight, water, and carbon dioxide to create their own food (glucose/sugars) and release oxygen, converting light energy into stored chemical energy, forming the base of most food webs and producing atmospheric oxygen. It involves light-dependent reactions (capturing energy in ATP/NADPH using chlorophyll) and light-independent reactions (Calvin Cycle) that use this energy to build sugars, occurring in chloroplasts.

Photosynthesis is the process where plants, algae, and some bacteria use sunlight, water, and carbon dioxide to create their own food (glucose/sugar) and release oxygen as a byproduct, converting light energy into stored chemical energy. This vital process, primarily occurring in chloroplasts, provides the energy and oxygen necessary for most life on Earth.

Summary

Photosynthesis is a system of biological processes by which photopigment-bearing autotrophic organisms, such as most plants, algae and cyanobacteria, convert light energy — typically from sunlight — into the chemical energy necessary to fuel their metabolism. The term photosynthesis usually refers to oxygenic photosynthesis, a process that releases oxygen as a byproduct of water splitting. Photosynthetic organisms store the converted chemical energy within the bonds of intracellular organic compounds (complex compounds containing carbon), typically carbohydrates like sugars (mainly glucose, fructose and sucrose), starches, phytoglycogen and cellulose. When needing to use this stored energy, an organism's cells then metabolize the organic compounds through cellular respiration. Photosynthesis plays a critical role in producing and maintaining the oxygen content of the Earth's atmosphere, and it supplies most of the biological energy necessary for complex life on Earth.

Some organisms also perform anoxygenic photosynthesis, which does not produce oxygen. Some bacteria (e.g. purple bacteria) use bacteriochlorophyll to split hydrogen sulfide as a reductant instead of water, releasing sulfur instead of oxygen, which was a dominant form of photosynthesis in the euxinic Canfield oceans during the Boring Billion. Archaea such as Halobacterium also perform a type of non-carbon-fixing anoxygenic photosynthesis, where the simpler photopigment retinal and its microbial rhodopsin derivatives are used to absorb green light and produce a proton (hydron) gradient across the cell membrane, and the subsequent ion movement powers transmembrane proton pumps to directly synthesize adenosine triphosphate (ATP), the "energy currency" of cells. Such archaeal photosynthesis might have been the earliest form of photosynthesis that evolved on Earth, as far back as the Paleoarchean, preceding that of cyanobacteria (see Purple Earth hypothesis).

While the details may differ between species, the process always begins when light energy is absorbed by the reaction centers, proteins that contain photosynthetic pigments or chromophores. In plants, these pigments are chlorophylls (a porphyrin derivative that absorbs the red and blue spectra of light, thus reflecting green) held inside chloroplasts, abundant in leaf cells. In cyanobacteria, they are embedded in the plasma membrane. In these light-dependent reactions, some energy is used to strip electrons from suitable substances, such as water, producing oxygen gas. The hydrogen freed by the splitting of water is used in the creation of two important molecules that participate in energetic processes: reduced nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NADPH) and ATP.

In plants, algae, and cyanobacteria, sugars are synthesized by a subsequent sequence of light-independent reactions called the Calvin cycle. In this process, atmospheric carbon dioxide is incorporated into already existing organic compounds, such as ribulose bisphosphate (RuBP). Using the ATP and NADPH produced by the light-dependent reactions, the resulting compounds are then reduced and removed to form further carbohydrates, such as glucose. In other bacteria, different mechanisms like the reverse Krebs cycle are used to achieve the same end.

The first photosynthetic organisms probably evolved early in the evolutionary history of life using reducing agents such as hydrogen or hydrogen sulfide, rather than water, as sources of electrons. Cyanobacteria appeared later; the excess oxygen they produced contributed directly to the oxygenation of the Earth, which rendered the evolution of complex life possible. The average rate of energy captured by global photosynthesis is approximately 130 terawatts, which is about eight times the total power consumption of human civilization. Photosynthetic organisms also convert around 100–115 billion tons (91–104 Pg petagrams, or billions of metric tons), of carbon into biomass per year. Photosynthesis was discovered in 1779 by Jan Ingenhousz who showed that plants need light, not just soil and water.

Details

Photosynthesis is the process by which green plants and certain other organisms transform light energy into chemical energy. During photosynthesis in green plants, light energy is captured and used to convert water, carbon dioxide, and minerals into oxygen and energy-rich organic compounds.

Importance of photosynthesis

It would be impossible to overestimate the importance of photosynthesis in the maintenance of life on Earth. The Great Oxidation Event, which began about 2.4 billion years ago and was largely driven by the photosynthetic cyanobacteria, raised atmospheric oxygen to nearly 1 percent of present levels over a span of 600 million years, paving the way for the evolution of most forms of multicellular life. Photosynthesis completely transformed Earth’s environment and biosphere. The life-giving process continues to sustain biodiversity since autotrophs are foundational to nearly every food web on the planet. If photosynthesis ceased, there would soon be little food or other organic matter on Earth. Most organisms would disappear, and in time Earth’s atmosphere would become nearly devoid of gaseous oxygen. The only organisms able to exist under such conditions would be the chemosynthetic bacteria, which can utilize the chemical energy of certain inorganic compounds and thus are not dependent on the conversion of light energy.

Energy produced by photosynthesis carried out by plants millions of years ago is responsible for the fossil fuels (i.e., coal, oil, and natural gas) that power industrial society. In past ages, green plants and small organisms that fed on plants increased faster than they were consumed, and their remains were deposited in Earth’s crust by sedimentation and other geological processes. There, protected from oxidation, these organic remains were slowly converted to fossil fuels. These fuels not only provide much of the energy used in factories, homes, and transportation but also serve as the raw material for plastics and other synthetic products. Unfortunately, modern civilization is using up in a few centuries the excess of photosynthetic production accumulated over millions of years. Consequently, the carbon dioxide that has been removed from the air to make carbohydrates in photosynthesis over millions of years is being returned at an incredibly rapid rate. The carbon dioxide concentration in Earth’s atmosphere is rising the fastest it ever has in Earth’s history, and this phenomenon—known as global warming—is expected to have major implications on Earth’s climate.

Evolution of the process

Although life and the quality of the atmosphere today depend on photosynthesis, it is likely that green plants evolved long after the first living cells. When Earth was young, electrical storms and solar radiation probably provided the energy for the synthesis of complex molecules from abundant simpler ones, such as water, ammonia, and methane. The first living cells probably evolved from these complex molecules. For example, the accidental joining (condensation) of the amino acid glycine and the fatty acid acetate may have formed complex organic molecules known as porphyrins. These molecules, in turn, may have evolved further into colored molecules called pigments—e.g., chlorophylls of green plants, bacteriochlorophyll of photosynthetic bacteria, hemin (the red pigment of blood), and cytochromes, a group of pigment molecules essential in both photosynthesis and cellular respiration.

Primitive colored cells then had to evolve mechanisms for using the light energy absorbed by their pigments. At first, the energy may have been used immediately to initiate reactions useful to the cell. As the process for using light energy continued to evolve, however, a larger part of the absorbed light energy probably was stored as chemical energy, to be used to maintain life. Green plants, with their ability to use light energy to convert carbon dioxide and water to carbohydrates and oxygen, are the culmination of this evolutionary process.

The first oxygenic (oxygen-producing) cells probably were the cyanobacteria (blue-green algae), which appeared about two billion to three billion years ago. These microscopic organisms are believed to have greatly increased the oxygen content of the atmosphere, making possible the development of aerobic (oxygen-using) organisms. Cyanophytes are prokaryotic cells; that is, they contain no distinct membrane-enclosed subcellular particles (organelles), such as nuclei and chloroplasts. Green plants, by contrast, are composed of eukaryotic cells, in which the photosynthetic apparatus is contained within membrane-bound chloroplasts. The complete genome sequences of cyanobacteria and higher plants provide evidence that the first photosynthetic eukaryotes were likely the red algae that developed when nonphotosynthetic eukaryotic cells engulfed cyanobacteria. Within the host cells, these cyanobacteria evolved into chloroplasts.

There are a number of photosynthetic bacteria that are not oxygenic (e.g., the sulfur bacteria previously discussed). The evolutionary pathway that led to these bacteria diverged from the one that resulted in oxygenic organisms. In addition to the absence of oxygen production, nonoxygenic photosynthesis differs from oxygenic photosynthesis in two other ways: light of longer wavelengths is absorbed and used by pigments called bacteriochlorophylls, and reduced compounds other than water (such as hydrogen sulfide or organic molecules) provide the electrons needed for the reduction of carbon dioxide.

Additional Information

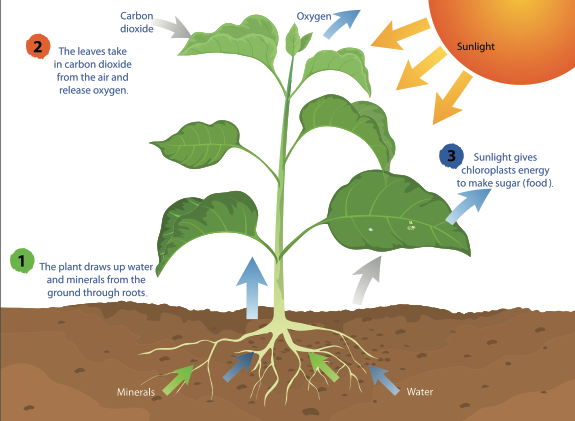

Photosynthesis is the process by which plants use sunlight, water, and carbon dioxide to create oxygen and energy in the form of sugar.

Most life on Earth depends on photosynthesis.The process is carried out by plants, algae, and some types of bacteria, which capture energy from sunlight to produce oxygen (O2) and chemical energy stored in glucose (a sugar). Herbivores then obtain this energy by eating plants, and carnivores obtain it by eating herbivores.

The process

During photosynthesis, plants take in carbon dioxide (CO2) and water (H2O) from the air and soil. Within the plant cell, the water is oxidized, meaning it loses electrons, while the carbon dioxide is reduced, meaning it gains electrons. This transforms the water into oxygen and the carbon dioxide into glucose. The plant then releases the oxygen back into the air, and stores energy within the glucose molecules.

Chlorophyll

Inside the plant cell are small organelles called chloroplasts, which store the energy of sunlight. Within the thylakoid membranes of the chloroplast is a light-absorbing pigment called chlorophyll, which is responsible for giving the plant its green color. During photosynthesis, chlorophyll absorbs energy from blue- and red-light waves, and reflects green-light waves, making the plant appear green.

Light-dependent Reactions vs. Light-independent Reactions

While there are many steps behind the process of photosynthesis, it can be broken down into two major stages: light-dependent reactions and light-independent reactions. The light-dependent reaction takes place within the thylakoid membrane and requires a steady stream of sunlight, hence the name light-dependent reaction. The chlorophyll absorbs energy from the light waves, which is converted into chemical energy in the form of the molecules ATP and NADPH. The light-independent stage, also known as the Calvin cycle, takes place in the stroma, the space between the thylakoid membranes and the chloroplast membranes, and does not require light, hence the name light-independent reaction. During this stage, energy from the ATP and NADPH molecules is used to assemble carbohydrate molecules, like glucose, from carbon dioxide.

C3 and C4 Photosynthesis

Not all forms of photosynthesis are created equal, however. There are different types of photosynthesis, including C3 photosynthesis and C4 photosynthesis. C3 photosynthesis is used by the majority of plants. It involves producing a three-carbon compound called 3-phosphoglyceric acid during the Calvin Cycle, which goes on to become glucose. C4 photosynthesis, on the other hand, produces a four-carbon intermediate compound, which splits into carbon dioxide and a three-carbon compound during the Calvin Cycle. A benefit of C4 photosynthesis is that by producing higher levels of carbon, it allows plants to thrive in environments without much light or water.

It appears to me that if one wants to make progress in mathematics, one should study the masters and not the pupils. - Niels Henrik Abel.

Nothing is better than reading and gaining more and more knowledge - Stephen William Hawking.

Offline