Math Is Fun Forum

You are not logged in.

- Topics: Active | Unanswered

- Index

- » This is Cool

- » Synapse

Pages: 1

#1 Yesterday 20:26:29

- Jai Ganesh

- Administrator

- Registered: 2005-06-28

- Posts: 53,133

Synapse

Synapse

Gist

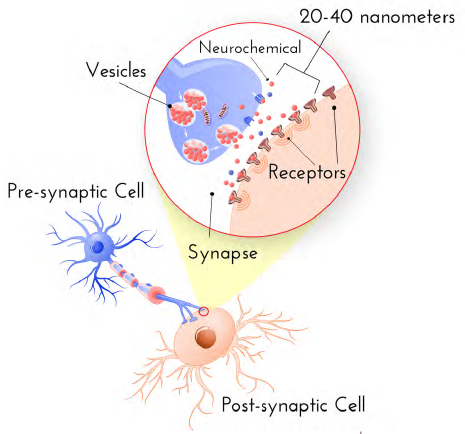

A synapse is the specialized junction in the brain where one neuron (nerve cell) communicates with another, or with a target cell like a muscle. These tiny, complex structures—roughly 20-40 nanometers wide—are the foundation of all brain function, including memory, learning, and thought, with the adult human brain containing an estimated 100 to 500 trillion of them.

Synapse is the transmission site from the pre-synaptic to the post-synaptic neuron. The structures found on either side of the synapse vary depending on the type of synapse: Axodendritic is a connection formed between the axon of 1 neuron and the dendrite of another. These tend to be excitatory synapses.

A synapse is a specialized junction in the nervous system that allows a neuron (nerve cell) to pass an electrical or chemical signal to another neuron or to a target effector cell (such as a muscle or gland). It is the fundamental site of communication in the brain, with the human brain containing hundreds of trillions to over one quadrillion synapses.

Summary

A synapse is the site of transmission of electric nerve impulses between two nerve cells (neurons) or between a neuron and a gland or muscle cell (effector). A synaptic connection between a neuron and a muscle cell is called a neuromuscular junction.

At a chemical synapse each ending, or terminal, of a nerve fibre (presynaptic fibre) swells to form a knoblike structure that is separated from the fibre of an adjacent neuron, called a postsynaptic fibre, by a microscopic space called the synaptic cleft. The typical synaptic cleft is about 0.02 micron wide. The arrival of a nerve impulse at the presynaptic terminals causes the movement toward the presynaptic membrane of membrane-bound sacs, or synaptic vesicles, which fuse with the membrane and release a chemical substance called a neurotransmitter. This substance transmits the nerve impulse to the postsynaptic fibre by diffusing across the synaptic cleft and binding to receptor molecules on the postsynaptic membrane. The chemical binding action alters the shape of the receptors, initiating a series of reactions that open channel-shaped protein molecules. Electrically charged ions then flow through the channels into or out of the neuron. This sudden shift of electric charge across the postsynaptic membrane changes the electric polarization of the membrane, producing the postsynaptic potential, or PSP. If the net flow of positively charged ions into the cell is large enough, then the PSP is excitatory; that is, it can lead to the generation of a new nerve impulse, called an action potential.

Once they have been released and have bound to postsynaptic receptors, neurotransmitter molecules are immediately deactivated by enzymes in the synaptic cleft; they are also taken up by receptors in the presynaptic membrane and recycled. This process causes a series of brief transmission events, each one taking place in only 0.5 to 4.0 milliseconds.

A single neurotransmitter may elicit different responses from different receptors. For example, norepinephrine, a common neurotransmitter in the autonomic nervous system, binds to some receptors that excite nervous transmission and to others that inhibit it. The membrane of a postsynaptic fibre has many different kinds of receptors, and some presynaptic terminals release more than one type of neurotransmitter. Also, each postsynaptic fibre may form hundreds of competing synapses with many neurons. These variables account for the complex responses of the nervous system to any given stimulus. The synapse, with its neurotransmitter, acts as a physiological valve, directing the conduction of nerve impulses in regular circuits and preventing random or chaotic stimulation of nerves.

Electric synapses allow direct communications between neurons whose membranes are fused by permitting ions to flow between the cells through channels called gap junctions. Found in invertebrates and lower vertebrates, gap junctions allow faster synaptic transmission as well as the synchronization of entire groups of neurons. Gap junctions are also found in the human body, most often between cells in most organs and between glial cells of the nervous system. Chemical transmission seems to have evolved in large and complex vertebrate nervous systems, where transmission of multiple messages over longer distances is required.

Details

In the nervous system, a synapse is a structure that allows a neuron (or nerve cell) to pass an electrical or chemical signal to another neuron or a target effector cell. Synapses can be classified as either chemical or electrical, depending on the mechanism of signal transmission between neurons. In the case of electrical synapses, neurons are coupled bidirectionally with each other through gap junctions and have a connected cytoplasmic milieu. These types of synapses are known to produce synchronous network activity in the brain, but can also result in complicated, chaotic network level dynamics. Therefore, signal directionality cannot always be defined across electrical synapses.

Chemical synapses, on the other hand, communicate through neurotransmitters released from the presynaptic neuron into the synaptic cleft. Upon release, these neurotransmitters bind to specific receptors on the postsynaptic membrane, inducing an electrical or chemical response in the target neuron. This mechanism allows for more complex modulation of neuronal activity compared to electrical synapses, contributing significantly to the plasticity and adaptable nature of neural circuits.

Synapses are essential for the transmission of neuronal impulses from one neuron to the next, playing a key role in enabling rapid and direct communication by creating circuits. In addition, a synapse serves as a junction where both the transmission and processing of information occur, making it a vital means of communication between neurons. In the human brain, most synapses are found in the grey matter of the cerebral and cerebellar cortices, as well as in the basal ganglia.

At the synapse, the plasma membrane of the signal-passing neuron (the presynaptic neuron) comes into close apposition with the membrane of the target (postsynaptic) cell. Both the presynaptic and postsynaptic sites contain extensive arrays of molecular machinery that link the two membranes together and carry out the signaling process. In many synapses, the presynaptic part is located on the terminals of axons and the postsynaptic part is located on a dendrite or soma. Astrocytes also exchange information with the synaptic neurons, responding to synaptic activity and, in turn, regulating neurotransmission. Synapses (at least chemical synapses) are stabilized in position by synaptic adhesion molecules (SAMs) projecting from both the pre- and post-synaptic neuron and sticking together where they overlap; SAMs may also assist in the generation and functioning of synapses. Moreover, SAMs coordinate the formation of synapses, with various types working together to achieve the remarkable specificity of synapses. In essence, SAMs function in both excitatory and inhibitory synapses, likely serving as the mediator for signal transmission.

Many mental illnesses are thought to be caused by synaptopathy.

History

Santiago Ramón y Cajal proposed that neurons are not continuous throughout the body, yet still communicate with each other, an idea known as the neuron doctrine. The word "synapse" was introduced in 1897 by the English neurophysiologist Charles Sherrington in Michael Foster's Textbook of Physiology. Sherrington struggled to find a good term that emphasized a union between two separate elements, and the actual term "synapse" was suggested by the English classical scholar Arthur Woollgar Verrall, a friend of Foster. The word was derived from the Greek synapsis, meaning "conjunction", which in turn derives from synaptein, from syn "together" and haptein "to fasten".

However, while the synaptic gap remained a theoretical construct, and was sometimes reported as a discontinuity between contiguous axonal terminations and dendrites or cell bodies, histological methods using the best light microscopes of the day could not visually resolve their separation which is now known to be about 20 nm. It needed the electron microscope in the 1950s to show the finer structure of the synapse with its separate, parallel pre- and postsynaptic membranes and processes, and the cleft between the two.

Types

Chemical and electrical synapses are two ways of synaptic transmission.

* In a chemical synapse, electrical activity in the presynaptic neuron is converted (via the activation of voltage-gated calcium channels) into the release of a chemical called a neurotransmitter that binds to receptors located in the plasma membrane of the postsynaptic cell. The neurotransmitter may initiate an electrical response or a secondary messenger pathway that may either excite or inhibit the postsynaptic neuron. Chemical synapses can be classified according to the neurotransmitter released: glutamatergic (often excitatory), GABAergic (often inhibitory), cholinergic (e.g. vertebrate neuromuscular junction), and adrenergic (releasing norepinephrine). Because of the complexity of receptor signal transduction, chemical synapses can have complex effects on the postsynaptic cell.

* In an electrical synapse, the presynaptic and postsynaptic cell membranes are connected by special channels called gap junctions that are capable of passing an electric current, causing voltage changes in the presynaptic cell to induce voltage changes in the postsynaptic cell. In fact, gap junctions facilitate the direct flow of electrical current without the need for neurotransmitters, as well as small molecules like calcium. Thus, the main advantage of an electrical synapse is the rapid transfer of signals from one cell to the next.

* Mixed chemical electrical synapses are synaptic sites that feature both a gap junction and neurotransmitter release. This combination allows a signal to have both a fast component (electrical) and a slow component (chemical).

The formation of neural circuits in nervous systems appears to heavily depend on the crucial interactions between chemical and electrical synapses. Thus these interactions govern the generation of synaptic transmission. Synaptic communication is distinct from an ephaptic coupling, in which communication between neurons occurs via indirect electric fields. An autapse is a chemical or electrical synapse that forms when the axon of one neuron synapses onto dendrites of the same neuron.

Excitatory and inhibitory

* Excitatory synapse: Enhances the probability of depolarization in postsynaptic neurons and the initiation of an action potential.

* Inhibitory synapse: Diminishes the probability of depolarization in postsynaptic neurons and the initiation of an action potential.

An influx of Na+ driven by excitatory neurotransmitters opens cation channels, depolarizing the postsynaptic membrane toward the action potential threshold. In contrast, inhibitory neurotransmitters cause the postsynaptic membrane to become less depolarized by opening either Cl- or K+ channels, reducing firing. Depending on their release location, the receptors they bind to, and the ionic circumstances they encounter, various transmitters can be either excitatory or inhibitory. For instance, acetylcholine can either excite or inhibit depending on the type of receptors it binds to. For example, glutamate serves as an excitatory neurotransmitter, in contrast to GABA, which acts as an inhibitory neurotransmitter. Additionally, dopamine is a neurotransmitter that exerts dual effects, displaying both excitatory and inhibitory impacts through binding to distinct receptors.

The membrane potential prevents Cl- from entering the cell, even when its concentration is much higher outside than inside. The reversal potential for Cl- in many neurons is quite negative, nearly equal to the resting potential. Opening Cl- channels tends to buffer the membrane potential, but this effect is countered when the membrane starts to depolarize, allowing more negatively charged Cl- ions to enter the cell. Consequently, it becomes more difficult to depolarize the membrane and excite the cell when Cl- channels are open. Similar effects result from the opening of K+ channels. The significance of inhibitory neurotransmitters is evident from the effects of toxins that impede their activity. For instance, strychnine binds to glycine receptors, blocking the action of glycine and leading to muscle spasms, convulsions, and death.

Interfaces

Synapses can be classified by the type of cellular structures serving as the pre- and post-synaptic components. The vast majority of synapses in the mammalian nervous system are classical axo-dendritic synapses (axon synapsing upon a dendrite), however, a variety of other arrangements exist. These include but are not limited to axo-axonic, dendro-dendritic, axo-secretory, axo-ciliary, somato-dendritic, dendro-somatic, and somato-somatic synapses.

In fact, the axon can synapse onto a dendrite, onto a cell body, or onto another axon or axon terminal, as well as into the bloodstream or diffusely into the adjacent nervous tissue.

Conversion of chemical into electrical signals

Neurotransmitters are tiny signal molecules stored in membrane-enclosed synaptic vesicles and released via exocytosis. A change in electrical potential in the presynaptic cell triggers the release of these molecules. By attaching to transmitter-gated ion channels, the neurotransmitter causes an electrical alteration in the postsynaptic cell and rapidly diffuses across the synaptic cleft. Once released, the neurotransmitter is swiftly eliminated, either by being absorbed by the nerve terminal that produced it, taken up by nearby glial cells, or broken down by specific enzymes in the synaptic cleft. Numerous Na+-dependent neurotransmitter carrier proteins recycle the neurotransmitters and enable the cells to maintain rapid rates of release.

At chemical synapses, transmitter-gated ion channels play a vital role in rapidly converting extracellular chemical impulses into electrical signals. These channels are located in the postsynaptic cell's plasma membrane at the synapse region, and they temporarily open in response to neurotransmitter molecule binding, causing a momentary alteration in the membrane's permeability. Additionally, transmitter-gated channels are comparatively less sensitive to the membrane potential than voltage-gated channels, which is why they are unable to generate self-amplifying excitement on their own. However, they result in graded variations in membrane potential due to local permeability, influenced by the amount and duration of neurotransmitter released at the synapse.

Release of neurotransmitters

Neurotransmitters bind to ionotropic receptors on postsynaptic neurons, either causing their opening or closing. The variations in the quantities of neurotransmitters released from the presynaptic neuron may play a role in regulating the effectiveness of synaptic transmission. In fact, the concentration of cytoplasmic calcium is involved in regulating the release of neurotransmitters from presynaptic neurons.

The chemical transmission involves several sequential processes:

1) Synthesizing neurotransmitters within the presynaptic neuron.

2) Loading the neurotransmitters into secretory vesicles.

3) Controlling the release of neurotransmitters into the synaptic cleft.

4) Binding of neurotransmitters to postsynaptic receptors.

5) Ceasing the activity of the released neurotransmitters.

Recently, mechanical tension, a phenomenon never thought relevant to synapse function has been found to be required for those on hippocampal neurons to fire.

Additional Information

The brain is responsible for every thought, feeling, and action. But how do the billions of cells that reside in the brain manage these feats?

They do so through a process called neurotransmission. Simply stated, neurotransmission is the way that brain cells communicate. And the bulk of those communications occur at a site called the synapse. Neuroscientists now understand that the synapse plays a critical role in a variety of cognitive processes—especially those involved with learning and memory.

What is a synapse?

The word synapse stems from the Greek words “syn” (together) and “haptein” (to clasp). This might make you think that a synapse is where brain cells touch or fasten together, but that isn’t quite right. The synapse, rather, is that small pocket of space between two cells, where they can pass messages to communicate. A single neuron may contain thousands of synapses. In fact, one type of neuron called the Purkinje cell, found in the brain’s cerebellum, may have as many as one hundred thousand synapses.

How big is a synapse?

Synapses are tiny—you cannot see them with the naked eye. When measured using sophisticated tools, scientists can see that the small gaps between cells is approximately 20-40 nanometers wide. If you consider that the thickness of a single sheet of paper is about 100,000 nanometers wide, you can start to understand just how small these functional contact points between neurons really are. More than 3,000 synapses would fit in that space alone!

How many synapses are in the human brain?

The short answer is that neuroscientists aren’t exactly sure. It’s very hard to measure in living human beings. But current post-mortem studies, where scientists examine the brains of deceased individuals, suggest that the average male human brain contains about 86 billion neurons. If each neuron is home to hundreds or even thousands of synapses, the estimated number of these communication points must be in the trillions.

Current estimates are listed somewhere around 0.15 quadrillion synapses—or 150,000,000,000,000 synapses.

What is synaptic transmission?

Generally speaking, it’s just another way to say neurotransmission. But it specifies that the communication occurring between brain cells is happening at the synapse as opposed to some other communication point. One neuron, often referred to as the pre-synaptic cell, will release a neurotransmitter or other neurochemical from special pouches clustered near the cell membrane called synaptic vesicles into the space between cells. Those molecules will then be taken up by membrane receptors on the post-synaptic, or neighboring, cell. When this message is passed between the two cells at the synapse, it has the power to change the behavior of both cells. Chemicals from the pre-synaptic neuron may excite the post-synaptic cell, telling it to release its own neurochemicals. It may tell the post-synaptic cell to slow down signaling or stop it all together. Or it may simply tell it to change the message a bit. But synapses offer the possibility of bi-directional communication. As such, post-synaptic cells can send back their own messages to pre-synaptic cells—telling them to change how much or how often a neurotransmitter is released.

Are there different kinds of synapses?

Yes! Synapses can vary in size, structure, and shape. And they can be found at different sites on a neuron. For example, there may be synapses between the axon of one cell and the dendrite of another, called axodendritic synapses. They can go from the axon to the cell body, or soma-that’s an axosomatic synapse. Or they may go between two axons. That’s an axoaxonic synapse.

There is also a special type of electrical synapse called a gap junction. They are smaller than traditional chemical synapses (only about 1-4 nanometers in width), and conduct electrical impulses between cells in a bidirectional fashion. Gap junctions come into play when neural circuits need to make quick and immediate responses.

While gap junctions don’t come up often in everyday neuroscience conversation, scientists now understand that they play an important role in the creation, maintenance, and strengthening of neural circuits. Some hypothesize gap junctions can “boost” neural signaling, helping to make sure signals will move far and wide across the cortex.

What is synaptic plasticity?

Synaptic plasticity is just a change of strength. Once upon a time, neuroscientists believed that all synapses were fixed-they worked at the same level all the time. But now, it’s understood that activity or lack thereof can strengthen or weaken synapses, or even change the number and structure of synapses in the brain. The more a synapse is used, the stronger it becomes and the more influence it can wield over its neighboring, post-synaptic neurons.

One type of synaptic plasticity is called long term potentiation (LTP). LTP occurs when brain cells on either side of a synapse repeatedly and persistently trade chemical signals, strengthening the synapse over time. This strengthening results in an amplified response in the post-synaptic cell. As such, LTP enhances cell communication, leading to faster and more efficient signaling between cells at the synapse. Neuroscientists believe that LTP underlies learning and memory in an area of the brain called the hippocampus. The strengthening of those synapses is what allows learning to occur, and, consequently, for memories to form.

It appears to me that if one wants to make progress in mathematics, one should study the masters and not the pupils. - Niels Henrik Abel.

Nothing is better than reading and gaining more and more knowledge - Stephen William Hawking.

Offline

Pages: 1

- Index

- » This is Cool

- » Synapse