Math Is Fun Forum

You are not logged in.

- Topics: Active | Unanswered

#1676 2025-01-19 16:39:55

- Jai Ganesh

- Administrator

- Registered: 2005-06-28

- Posts: 53,367

Re: crème de la crème

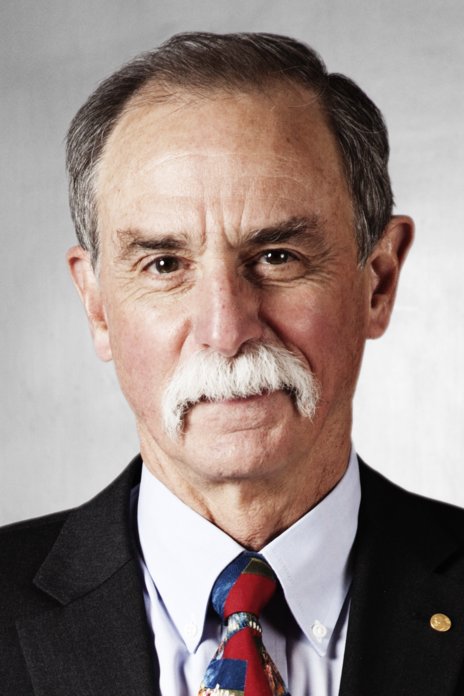

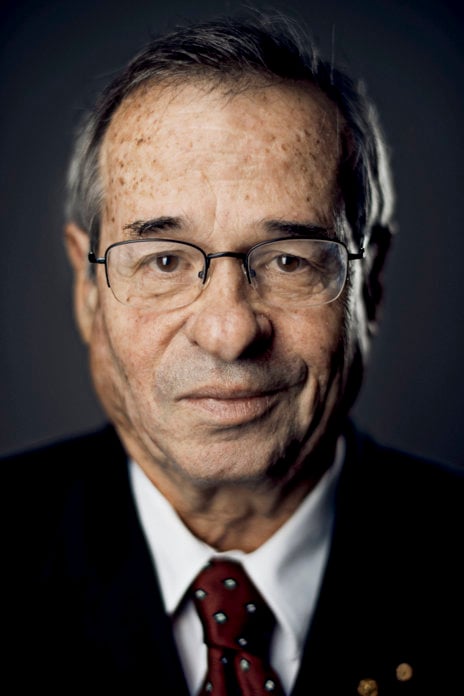

2139) David J. Wineland

Gist:

Life

David Wineland was born in Milwaukee, Wisconsin in the United States. He first studied at the University of California, Berkeley, and later earned his PhD from Harvard University under the supervision of Norman Ramsey. After completing his PhD, Wineland worked in a team led by Hans Dehmelt at the University of Washington in Seattle. Since 1975 he has worked at the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) and is also associated with the University of Colorado Boulder. He is married with two children.

Work

When it comes to the smallest components of our universe, our usual understanding of how the world works ceases to apply. We have entered the realm of quantum physics. For a long time, many quantum phenomena could only be examined theoretically. Starting in the late 1970s, David Wineland has designed ingenious experiments to study quantum phenomena when matter and light interact. Using electric fields, Wineland has successfully captured electrically charged atoms, or ions, in a kind of trap and studied them with the help of small packets of light, or photons.

Summary

David Wineland (born February 24, 1944, Wauwatosa, Wisconsin, U.S.) is an American physicist who was awarded the 2012 Nobel Prize for Physics for devising methods to study the quantum mechanical behaviour of individual ions. He shared the prize with French physicist Serge Haroche.

Wineland received a bachelor’s degree in physics from the University of California, Berkeley, in 1965 and a doctorate in physics from Harvard University in 1970. He was then a postdoctoral researcher at the University of Washington, and from 1975 to 2017 he worked at the National Institute of Standards and Technology in Boulder, Colorado. He later taught at the University of Oregon.

Wineland’s work concentrated on studying individual ions trapped in an electric field. Beginning in 1978 he and his collaborators used laser pulses of light at specific wavelengths to cool the ions to their lowest energy state, and in 1995 they placed the ions in a superposition of two different quantum states. Placing an ion in a superposed state allowed the study of quantum mechanical behaviour that had previously only been the subject of thought experiments, such as the famous Schrödinger’s cat. (In the 1930s German physicist Erwin Schrödinger, as a demonstration of the philosophical paradoxes involved in quantum theory, proposed a closed box in which a cat whose life depends on the possible radioactive decay of a particle would be both alive and dead until it is directly observed.)

On the practical side, Wineland’s group in 1995 used trapped ions to perform logical operations in one of the first demonstrations of quantum computing. In the early 2000s Wineland’s group used trapped ions to create an atomic clock much more accurate than those using cesium. In 2010 they used their clock to test Einstein’s theory of relativity on very small scales, detecting time dilation at speeds of only 36 km (22 miles) per hour and gravitational time dilation between two clocks spaced vertically only 33 cm (13 inches) apart.

Details

David Jeffery Wineland (born February 24, 1944) is an American physicist at the Physical Measurement Laboratory of the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST). His most notable contributions include the laser cooling of trapped ions and the use of ions for quantum-computing operations. He received the 2012 Nobel Prize in Physics, jointly with Serge Haroche, for "ground-breaking experimental methods that enable measuring and manipulation of individual quantum systems."

Early life and career

Wineland was born in Wauwatosa, Wisconsin. He lived in Denver until he was three years old, at which time his family moved to Sacramento, California. Wineland graduated from Encina High School in Sacramento in 1961. In Sept. 1961–Dec. 1963, he studied at University of California, Davis. He received his bachelor's degree in physics from the University of California, Berkeley in 1965 and his master's and doctoral degrees in physics from Harvard University. He completed his PhD in 1970, supervised by Norman Foster Ramsey, Jr. His doctoral dissertation is titled "The Atomic Deuterium Maser". He then performed postdoctoral research in Hans Dehmelt's group at the University of Washington where he investigated electrons in ion traps. In 1975, he joined the National Bureau of Standards (now called NIST), where he started the ion storage group and is on the physics faculty of the University of Colorado at Boulder. In January 2018, Wineland moved to the Department of Physics University of Oregon as a Knight Research Professor, while still being engaged with the Ion Storage Group at NIST in a consulting role.

Wineland was the first to laser-cool ions in 1978. His NIST group uses trapped ions in many experiments on fundamental physics, and quantum state control. They have demonstrated optical techniques to prepare ground, superposition and entangled states. This work has led to advances in spectroscopy, atomic clocks and quantum information. In 1995 he created the first single atom quantum logic gate and was the first to quantum teleport information in massive particles in 2004. Wineland implemented the most precise atomic clock using quantum logic on a single aluminum ion in 2005.

Wineland is a fellow of the American Physical Society and the Optical Society of America, and was elected to the National Academy of Sciences in 1992. He shared the 2012 Nobel Prize in Physics with French physicist Serge Haroche "for ground-breaking experimental methods that enable measuring and manipulation of individual quantum systems."

Family

Wineland is married to Sedna Quimby-Wineland, and they have two sons.

Sedna Helen Quimby is the daughter of George I. Quimby (1913-2003), an archaeologist and anthropologist, who was Professor of Anthropology at the University of Washington and Director of the Thomas Burke Memorial Washington State Museum, and his wife Helen Ziehm Quimby.

It appears to me that if one wants to make progress in mathematics, one should study the masters and not the pupils. - Niels Henrik Abel.

Nothing is better than reading and gaining more and more knowledge - Stephen William Hawking.

Offline

#1677 2025-01-20 15:51:32

- Jai Ganesh

- Administrator

- Registered: 2005-06-28

- Posts: 53,367

Re: crème de la crème

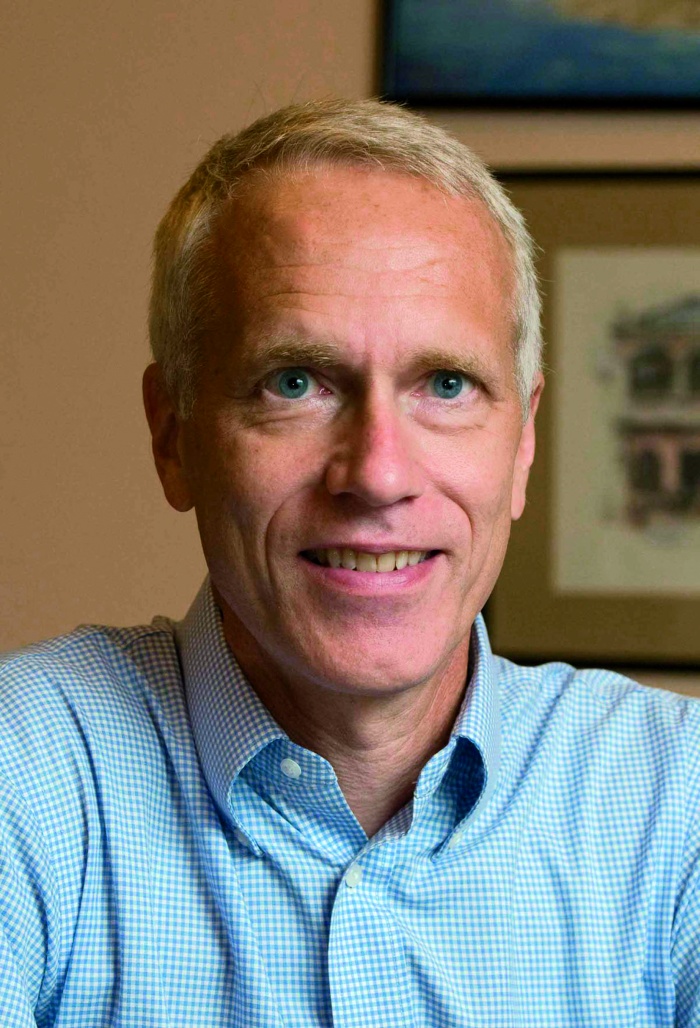

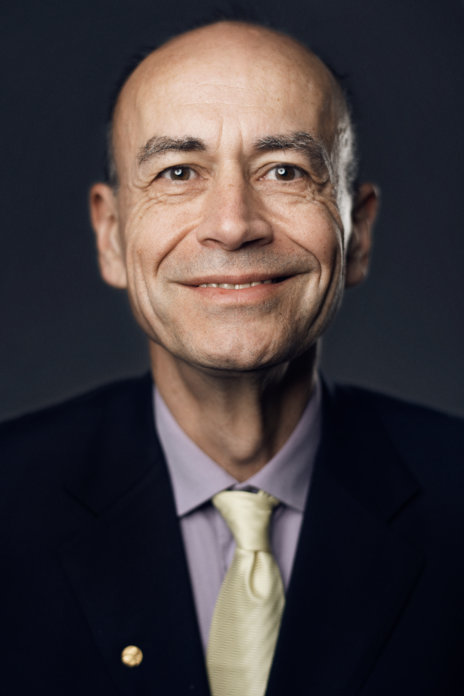

2140) Brian Kobilka

Gist:

Brian Kent Kobilka (born May 30, 1955) is an American physiologist and a recipient of the 2012 Nobel Prize in Chemistry with Robert Lefkowitz for discoveries that reveal the workings of G protein-coupled receptors.

Summary

Brian K. Kobilka (born May 30, 1955, Little Falls, Minnesota, U.S.) is an American physician and molecular biologist whose research on the structure and function of cell-surface molecules known as G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs)—the largest family of signal-receiving molecules found in organisms—contributed to profound advances in cell biology and medicine. For his discoveries, Kobilka shared the 2012 Nobel Prize for Chemistry with American physician and molecular biologist Robert J. Lefkowitz.

Kobilka graduated with B.S. degrees in biology and chemistry in 1977 from the University of Minnesota Duluth and then enrolled at Yale University in New Haven, Connecticut, to study medicine. He received an M.D. from Yale in 1981. Three years later, after completing a residency in internal medicine at Barnes Hospital (later Barnes-Jewish Hospital) at Washington University Medical Center in St. Louis, Missouri, Kobilka joined Lefkowitz’s laboratory at Duke University Medical Center in Durham, North Carolina. There, working as a postdoctoral fellow, he successfully pieced together the full DNA sequence for the mammalian beta2-adrenergic receptor from fragments of genomic DNA that had been amplified in genetically engineered bacteria. (Lefkowitz’s team previously had struggled to sequence the receptor because of its limited natural production in cells.) Kobilka’s feat demonstrated his talent for technological innovation and made possible the team’s groundbreaking realization that all GPCRs possess seven domains that cross the cell membrane, each of which served a fundamental role in receptor activity.

In 1989–90 Kobilka established a laboratory at Stanford University, where he had received a professorship in medicine and molecular and cellular physiology. He continued to investigate the relationship between GPCR structure and function, using adrenergic receptors as model systems. He became known for his application of innovative biophysical techniques, most notably his use of X-ray crystallography, in which an X-ray beam is projected onto a protein crystal to create a diffraction pattern that can then be used to deduce the protein’s atomic structure in three dimensions. Kobilka spent two decades working out a process to generate protein crystals of the beta2-adrenergic receptor that were sufficiently large for synchrotron analysis. The receptor’s shifting conformation further complicated the crystallization process. In 2011, however, having enlisted the help of colleagues in the United States and Europe, Kobilka finally published the first high-resolution view of transmembrane signaling by the beta2 receptor. The development was considered a milestone in biology and made possible the production of crystals of other GPCRs. Of particular significance was the opportunity to investigate the structures of GPCRs of pharmacological relevance, which could facilitate the development of drugs that targeted specific receptors, thereby enhancing therapeutic benefits while minimizing side effects.

Kobilka was a founder of the biotech company ConfometRx, which focused on the development of GPCR-based drug discovery technologies. He was elected to the National Academy of Sciences in 2011.

Details

Brian Kent Kobilka (born May 30, 1955) is an American physiologist and a recipient of the 2012 Nobel Prize in Chemistry with Robert Lefkowitz for discoveries that reveal the workings of G protein-coupled receptors. He is currently a professor in the department of Molecular and Cellular Physiology at Stanford University School of Medicine. He is also a co-founder of ConfometRx, a biotechnology company focusing on G protein-coupled receptors. He was named a member of the National Academy of Sciences in 2011.

Early life

Kobilka attended St. Mary's Grade School in Little Falls, Minnesota, a part of the Roman Catholic Diocese of Saint Cloud. He then graduated from Little Falls High School. He received a Bachelor’s Degree in Biology and Chemistry from the University of Minnesota Duluth, and earned his M.D., cum laude, from Yale University School of Medicine. Following the completion of his residency in internal medicine at Washington University in St. Louis School of Medicine's Barnes-Jewish Hospital. Kobilka worked in research as a postdoctoral fellow under Robert Lefkowitz at Duke University, where he started work on cloning the β2-adrenergic receptor. Kobilka moved to Stanford in 1989. He was a Howard Hughes Medical Institute (HHMI) investigator from 1987 to 2003.

Research

Kobilka is best known for his research on the structure and activity of G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs); in particular, work from Kobilka's laboratory determined the molecular structure of the β2-adrenergic receptor. This work has been highly cited by other scientists because GPCRs are important targets for pharmaceutical therapeutics, but notoriously difficult to work with in X-ray crystallography. Before, rhodopsin was the only G-protein coupled receptor where the structure had been determined at high resolution. The β2-adrenergic receptor structure was soon followed by the determination of the molecular structure of several other G-protein coupled receptors.

Kobilka is the 1994 recipient of the American Society for Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics John J. Abel Award in Pharmacology. His GPCR structure work was named "runner-up" for the 2007 "Breakthrough of the Year" award from Science. The work was, in part, supported by Kobilka's 2004 Javits Neuroscience Investigator Award from the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke. He received the 2012 Nobel Prize in Chemistry with Robert Lefkowitz for his work on G protein-coupled receptors. In 2017, Kobilka received the Golden Plate Award of the American Academy of Achievement.

As part of Shenzhen’s 13th Five-Year Plan funding research in emerging technologies and opening "Nobel laureate research labs", in 2017 he opened the Kobilka Institute of Innovative Drug Discovery at the Chinese University of Hong Kong, Shenzhen in Southern China.

Personal life

Kobilka is from Little Falls in central Minnesota. Both his grandfather Felix J. Kobilka (1893–1991) and his father Franklyn A. Kobilka (1921–2004) were bakers and natives of Little Falls, Minnesota. Kobilka's grandmother, Isabelle Susan Kobilka (née Medved, 1891–1980), belonged to the Medved and Kiewel families of Prussian immigrants, who from 1888 owned the historical Kiewel brewery in Little Falls. His mother is Betty L. Kobilka (née Faust, b. 1930).

Kobilka met his wife Tong Sun Thian, a Malaysian-Chinese woman, at the University of Minnesota Duluth. They have two children, Jason and Megan Kobilka.

Additional Information

Brian Kent Kobilka (born May 30, 1955) is an American physiologist. He is best known for his work with G protein-coupled receptors, for which he was awarded the 2012 Nobel Prize for Chemistry with Robert Lefkowitz.He is currently a professor in the department of Molecular and Cellular Physiology at Stanford University School of Medicine. He was named a member of the National Academy of Sciences in 2011.

It appears to me that if one wants to make progress in mathematics, one should study the masters and not the pupils. - Niels Henrik Abel.

Nothing is better than reading and gaining more and more knowledge - Stephen William Hawking.

Offline

#1678 2025-01-21 16:11:17

- Jai Ganesh

- Administrator

- Registered: 2005-06-28

- Posts: 53,367

Re: crème de la crème

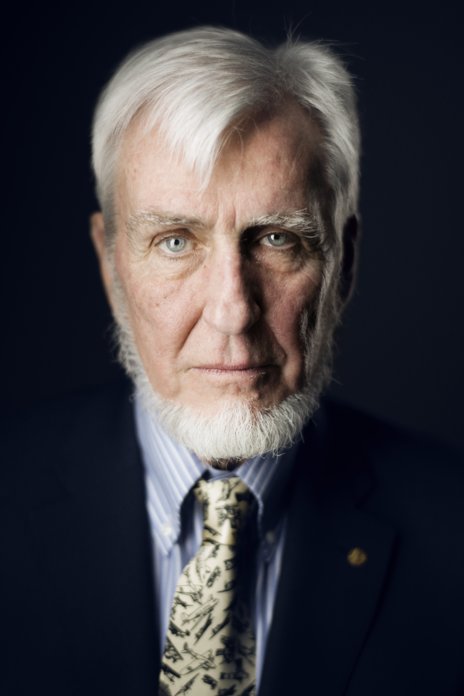

2141) Robert Lefkowitz

Gist:

Life

Robert Lefkowitz was born and raised in New York in a family with Polish heritage. He studied chemistry and trained to become a doctor at Columbia University. Since 1973 he has worked at Duke University and the Howard Hughes Medical Institute in Durham, North Carolina. Robert Lefkowitz is married with five children.

Work

Communication between the cells in your body are managed by substances called hormones. Each cell has a small receiver known as a receptor, which is able to receive hormones. In order to track these receptors, in 1968 Robert Lefkowitz attached a radioactive isotope of iodine to the hormone adrenaline. By tracking the radiation emitted by the isotope, he succeeded in finding a receptor for adrenaline and studied how it functions. It was later discovered that there is an entire family of receptors that look and act in similar ways–G-protein-coupled receptors. Approximately half of all medications used today make use of this kind of receptor.

Summary

Robert J. Lefkowitz (born April 15, 1943, Bronx, New York, U.S.) is an American physician and molecular biologist who demonstrated the existence of receptors—molecules that receive and transmit signals for cells. His research on the structure and function of cell-surface receptors—particularly of G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs), the largest family of signal-receiving molecules found in organisms—revolutionized scientists’ understanding of how cells respond to stimuli such as hormones and how certain types of drugs exert their actions, leading to major advances in drug development. For his groundbreaking discoveries, Lefkowitz shared the 2012 Nobel Prize for Chemistry with American physician and molecular biologist Brian K. Kobilka.

In 1959 Lefkowitz graduated from the Bronx High School of Science. He received a scholarship to study at Columbia College, Columbia University, New York, where he earned a B.A. in chemistry in 1962. Having decided at an early age that he wanted to be a physician, he remained in New York to study at the Columbia University College of Physicians and Surgeons, receiving an M.D. in 1966. Two years later, after a residency at Columbia, he took a position at the National Institute of Arthritis and Metabolic Diseases (NIAMD; later the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases), part of the National Institutes of Health in Maryland, where he set to work on validating the existence of receptors. His initial research focused on developing a procedure (an assay) by which radioactively labeled adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) would bind specifically to the membranes of cancer cells; such an assay would facilitate the purification of receptors. By 1970 he had successfully developed the procedure and had published evidence for the existence of cell-surface receptors. That year he left NIAMD for a residency and training in cardiovascular disease at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston. In 1972, while working in the laboratory of German American physician and researcher Edgar Haber, he published a report detailing his purification of beta-adrenergic receptor protein from heart muscle cells (cardiomyocytes) in dogs. The beta-adrenergic receptor would later become a model system for the study of GPCRs.

In 1973 Lefkowitz joined the faculty at the Duke University Medical Center in Durham, North Carolina, where he later found that adrenergic receptors transmit signals to an intracellular molecule called a G protein (guanine nucleotide-binding protein), which had been discovered earlier by American pharmacologist Alfred G. Gilman and American biochemist Martin Rodbell (Gilman and Rodbell shared the 1994 Nobel Prize for Physiology or Medicine for their independent discovery of G proteins). When activated, G proteins stimulate an enzyme known as adenylate cyclase, which converts the energy-carrying molecule ATP (adenosine triphosphate) to cAMP (cyclic adenosine monophosphate), a process responsible for producing physiological responses prompted by hormone-receptor binding. Lefkowitz also discovered a molecule known as beta-adrenergic receptor kinase (beta-ARK), which regulates GPCR activity.

In 1984 Kobilka joined Lefkowitz’s research group at Duke. Lefkowitz was then trying to determine the DNA sequence of the beta2-adrenergic receptor. Kobilka proceeded to piece together the DNA sequence using bacteria that had been genetically engineered to produce large quantities of genomic DNA, thereby overcoming the limitations imposed by the receptor’s restricted natural production in cells. Kobilka’s breakthrough facilitated the team’s discovery that all GPCRs possess seven domains that cross through the cell membrane; those domains were found to be fundamental to the receptors’ activity. Lefkowitz later identified a protein called beta-arrestin, which acts on beta-ARK-phosphorylated GPCRs and which explained the phenomenon of GPCR desensitization in response to repeated agonist binding.

In addition to the 2012 Nobel Prize, Lefkowitz was the recipient of several other major awards, including the 2007 Shaw Prize in Life Science and Medicine and the 2007 National Medal of Science, presented to him by U.S. Pres. George W. Bush. In 1988 Lefkowitz was elected a member of the National Academy of Sciences and the American Academy of Arts and Sciences.

Details

Robert Joseph Lefkowitz (born April 15, 1943) is an American physician (internist and cardiologist) and biochemist. He is best known for his discoveries that reveal the inner workings of an important family of G protein-coupled receptors, for which he was awarded the 2012 Nobel Prize for Chemistry with Brian Kobilka. He is currently an Investigator with the Howard Hughes Medical Institute as well as a James B. Duke Professor of Medicine and Professor of Biochemistry and Chemistry at Duke University.

Early life

Lefkowitz was born on April 15, 1943, in The Bronx, New York to Jewish parents Max and Rose Lefkowitz. Their families had emigrated to the United States from Poland in the late 19th century.

After graduating from the Bronx High School of Science in 1959, he attended Columbia College from which he received a Bachelor of Arts in chemistry in 1962. At Columbia, Lefkowitz studied under Ronald Breslow.

He graduated from Columbia University College of Physicians and Surgeons in 1966 with an M.D. degree. After serving an internship and one year of general medical residency at the College of Physicians and Surgeons, he served as clinical and research associate at the National Institutes of Health from 1968 to 1970.

Career

Upon completing his medical residency and research and clinical training in 1973, he was appointed associate professor of medicine and assistant professor of biochemistry at the Duke University Medical Center. In 1977, he was promoted to professor of medicine and in 1982 to James B. Duke Professor of Medicine at Duke University. He is also a professor of biochemistry and a professor of chemistry. He has been an investigator of the Howard Hughes Medical Institute since 1976 and was an established investigator of the American Heart Association from 1973 to 1976.

Lefkowitz studies receptor biology and signal transduction and is most well known for his detailed characterizations of the sequence, structure and function of the β-adrenergic and related receptors and for the discovery and characterization of the two families of proteins which regulate them, the G protein-coupled receptor (GPCR) kinases and β-arrestins.

Lefkowitz made a remarkable contribution in the mid-1980s when he and his colleagues cloned the gene first for the β-adrenergic receptor, and then rapidly thereafter, for a total of 8 adrenergic receptors (receptors for adrenaline and noradrenaline). This led to the seminal discovery that all GPCRs (which include the β-adrenergic receptor) have a very similar molecular structure. The structure is defined by an amino acid sequence which weaves its way back and forth across the plasma membrane seven times. Today we know that about 1,000 receptors in the human body belong to this same family. The importance of this is that all of these receptors use the same basic mechanisms so that pharmaceutical researchers now understand how to effectively target the largest receptor family in the human body. Today, as many as 30 to 50 percent of all prescription drugs are designed to "fit" like keys into the similarly structured locks of Lefkowitz' receptors—everything from anti-histamines to ulcer drugs to beta blockers that help relieve hypertension, angina and coronary disease. Lefkowitz is among the most highly cited researchers in the fields of biology, biochemistry, pharmacology, toxicology, and clinical medicine according to Thomson-ISI.

Personal life

Lefkowitz is married to Lynn (née Tilley). He has five children and six grandchildren. He was previously married to Arna Brandel.

In 2021, Lefkowitz published a memoir entitled A Funny Thing Happened on the Way to Stockholm: The Adrenaline-Fueled Adventures of an Accidental Scientist. This book was co-authored by Randy Hall, who was a post-doctoral fellow in the Lefkowitz lab in the 1990s. The book describes Lefkowitz's early life, training as a physician, and tenure in the United States Public Health Service (the "Yellow Berets" of the NIH), which began as a means of fulfilling his draft obligation during the Vietnam War but ultimately ignited a lifelong passion for research. The second half of the book describes Lefkowitz's research career and various adventures both before and after his Nobel Prize win. Upon publication in February 2021, the book was named as "New & Noteworthy" by The New York Times and "one of the week's best science picks" by Nature.

It appears to me that if one wants to make progress in mathematics, one should study the masters and not the pupils. - Niels Henrik Abel.

Nothing is better than reading and gaining more and more knowledge - Stephen William Hawking.

Offline

#1679 2025-01-22 16:49:10

- Jai Ganesh

- Administrator

- Registered: 2005-06-28

- Posts: 53,367

Re: crème de la crème

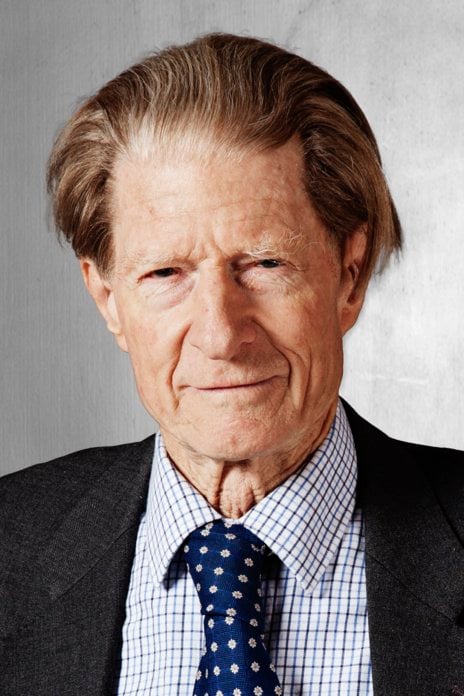

2142) John Gurdon

Gist:

Life

John Gurdon was born in Dippenhall, Hampshire, UK. He studied at Eton College boarding school, although his grades were not particularly good. A report written by one of his teachers called his ambition to devote himself to science ridiculous. Gurdon pursued his dream nonetheless, and went on to earn his PhD from Oxford University. After spending some years at the California Institute of Technology in Pasadena, Gurdon returned to Oxford in 1962. He has been affiliated with Cambridge University since 1971. John Gurdon is married with two children.

Work

Our lives begin when a fertilized egg divides and forms new cells that, in turn, also divide. These cells are identical in the beginning, but become increasingly varied over time. It was long thought that a mature or specialized cell could not return to an immature state, but this has now been proven incorrect. In 1962, John Gurdon removed the nucleus of a fertilized egg cell from a frog and replaced it with the nucleus of a cell taken from a tadpole's intestine. This modified egg cell grew into a new frog, proving that the mature cell still contained the genetic information needed to form all types of cells.

Summary

John Gurdon (born October 2, 1933, Dippenhall, Hampshire, England) is a British developmental biologist who was the first to demonstrate that egg cells are able to reprogram differentiated (mature) cell nuclei, reverting them to a pluripotent state, in which they regain the capacity to become any type of cell. Gurdon’s work ultimately came to form the foundation for major advances in cloning and stem cell research, including the generation of Dolly—the first successfully cloned mammal—by British developmental biologist Sir Ian Wilmut and the discovery of induced pluripotent stem (iPS) cells by Japanese physician and researcher Shinya Yamanaka—an advance that revolutionized the field of regenerative medicine. For his discoveries, Gurdon was awarded the 2012 Nobel Prize for Physiology or Medicine, which he shared with Yamanaka.

Gurdon studied classics (ancient Greek and Roman language and literature) as a student at Eton College, a prestigious secondary school for boys near Windsor, England. He intended to continue his classics studies at Christ Church, Oxford, but was not accepted to the program. Instead, after being tutored in zoology, he gained acceptance to that department at Oxford, earning a B.S. in 1956. That year he began his graduate studies in the laboratory of embryologist Michail Fischberg and initiated a series of experiments on nuclear transfer (the introduction of the nucleus from a differentiated cell into an egg cell that had its own nucleus removed) in the African clawed frog (Xenopus laevis). He proceeded to generate cloned tadpoles from differentiated Xenopus intestinal cell nuclei, demonstrating that egg cells could undifferentiate previously differentiated nuclei and that normal embryos could be produced with the technique. He published his seminal findings in 1958. However, because American scientists Robert Briggs and Thomas King previously had found that the transfer of nuclei from partially differentiated cells consistently resulted in the production of abnormal embryos in the frog Rana pipiens, Gurdon’s results were greeted with skepticism.

After completing a Ph.D. in 1960, Gurdon received a yearlong postdoctoral fellowship to conduct research at the California Institute of Technology in Pasadena, where he investigated the genetics of bacteria-infecting viruses (bacteriophages). He then returned to Oxford, becoming a faculty member in the zoology department and continuing his work to characterize nuclear changes that take place during cell differentiation.

Details

Sir John Bertrand Gurdon FRS (born 2 October 1933) is a British developmental biologist, best known for his pioneering research in nuclear transplantation and cloning.

Awarded the Lasker Award in 2009, in 2012, he and Shinya Yamanaka were jointly awarded the Nobel Prize for Physiology or Medicine for the discovery that mature cells can be converted to stem cells.

Career

Gurdon attended Edgeborough prep school before Eton College, where he ranked last out of the 250 boys in his year group at biology, and was in the bottom set in every other science subject. A schoolmaster wrote a report stating, "I believe he has ideas about becoming a scientist; on his present showing this is quite ridiculous." Gurdon explains it is the only document he ever framed; he also told a reporter: "When you have problems like an experiment doesn't work, which often happens, it's nice to remind yourself that perhaps after all you are not so good at this job and the schoolmaster may have been right!"

Gurdon went up to Christ Church, Oxford, to read classics then switched to zoology, graduating as MA. For his DPhil degree he studied nuclear transplantation in a frog species of the genus Xenopus, supervised by Dr Michail Fischberg at Oxford University. After pursuing further postdoctoral work at Caltech, he returned to England where his early posts were in the Department of Zoology at the University of Oxford (1962–71).

Gurdon spent much of his research career at the MRC Laboratory of Molecular Biology (1971–83) and then in the Department of Zoology (1983–present). In 1989, he became a founding member of the Wellcome/CRC Institute for Cell Biology and Cancer (later Wellcome/CR UK) at Cambridge, becoming its chairman until 2001. He served as a member of the Nuffield Council on Bioethics 1991–1995, then Master of Magdalene College, Cambridge, from 1995 to 2002.

Gurdon married Jean Elizabeth Margaret Curtis, by whom he has a son and a daughter.

Research:

Nuclear transfer

In 1958, Gurdon, then at the University of Oxford, successfully cloned a frog using intact nuclei from the somatic cells of a Xenopus tadpole. This work was an important extension of work of Briggs and King in 1952 on transplanting nuclei from embryonic blastula cells and the successful induction of polyploidy in the stickleback, Gasterosteus aculatus, in 1956 by Har Swarup reported in Nature. At that time he could not conclusively show that the transplanted nuclei derived from a fully differentiated cell. This was finally shown in 1975 by a group working at the Basel Institute for Immunology in Switzerland. They transplanted a nucleus from an antibody-producing lymphocyte (proof that it was fully differentiated) into an enucleated egg and obtained living tadpoles.

Gurdon's experiments captured the attention of the scientific community as it altered the notion of development and the tools and techniques he developed for nuclear transfer are still used today. The term clone (from the ancient Greek word (klōn, "twig")) had already been in use since the beginning of the 20th century in reference to plants. In 1963 the British biologist J. B. S. Haldane, in describing Gurdon's results, became one of the first to use the word "clone" in reference to animals.

Messenger RNA expression

Gurdon and colleagues also pioneered the use of Xenopus (genus of highly aquatic frog) eggs and oocytes to translate microinjected messenger RNA molecules, a technique which has been widely used to identify the proteins encoded and to study their function.

Recent research

Gurdon's recent research has focused on analysing intercellular signalling factors involved in cell differentiation, and on elucidating the mechanisms involved in reprogramming the nucleus in transplantation experiments, including the role of histone variants, and demethylation of the transplanted DNA.

Nobel Prize

In 2012, Gurdon was awarded, jointly with Shinya Yamanaka, the Nobel Prize for Physiology or Medicine "for the discovery that mature cells can be reprogrammed to become pluripotent". His Nobel Lecture was called "The Egg and the Nucleus: A Battle for Supremacy".

It appears to me that if one wants to make progress in mathematics, one should study the masters and not the pupils. - Niels Henrik Abel.

Nothing is better than reading and gaining more and more knowledge - Stephen William Hawking.

Offline

#1680 2025-01-23 15:47:00

- Jai Ganesh

- Administrator

- Registered: 2005-06-28

- Posts: 53,367

Re: crème de la crème

2143) Shinya Yamanaka

Gist:

Life

Shinya Yamanaka was born in Higashiosaka, Japan. He studied for his medical degree at Kobe University and later earned his PhD from Osaka City University in 1993. After spending several years at the Gladstone Institute at the University of California, San Francisco, he returned to Osaka, but later moved to the Nara Institute of Science and Technology, where he began his Nobel Prize-winning research. Yamanaka has been affiliated with Kyoto University since 2004. Shinya Yamanaka is married with two daughters.

Work

Our lives begin when a fertilized egg divides and forms new cells that, in turn, also divide. These cells are identical in the beginning, but become increasingly varied over time. It was long thought that a mature or specialized cell could not return to an immature state, but this has now been proven incorrect. In 2006, Shinya Yamanaka succeeded in identifying a small number of genes within the genome of mice that proved decisive in this process. When activated, skin cells from mice could be reprogrammed to immature stem cells, which, in turn, can grow into different types of cells within the body.

Summary

Shinya Yamanaka (born September 4, 1962, Ōsaka, Japan) is a Japanese physician and researcher who developed a revolutionary method for generating stem cells from existing cells of the body. This method involved inserting specific genes into the nuclei of adult cells (e.g., connective-tissue cells), a process that resulted in the reversion of cells from an adult state to a pluripotent state. As pluripotent cells, they had regained the capacity to differentiate into any cell type of the body. Thus, the reverted cells became known as induced pluripotent stem (iPS) cells. Yamanaka and British developmental biologist John B. Gurdon shared the 2012 Nobel Prize for Physiology or Medicine for the discovery that mature cells could be reprogrammed.

Yamanaka received an M.D. from Kōbe University in 1987 and a Ph.D. in pharmacology from the Ōsaka City University Graduate School in 1993. That year he joined the Gladstone Institute of Cardiovascular Disease, San Francisco, where he began investigating the c-Myc gene in different strains of knockout mice (mice in which a specific gene has been rendered nonfunctional in order to investigate the gene’s function). In 1996 Yamanaka returned to Ōsaka City University, where he remained until 1999, when he took a position at the Nara Institute of Science and Technology. During this period his research became increasingly focused on stem cells. In 2004 he moved to the Institute for Frontier Medical Sciences at Kyōto University, where he began his landmark studies on finding ways to induce pluripotency in cells. Yamanaka again sought research opportunities in the United States and subsequently was awarded funding that allowed him to split his time between Kyōto and the Gladstone Institute of Cardiovascular Disease. Yamanaka became a senior investigator at the Gladstone Institute in 2007.

In 2006 Yamanaka announced that he had succeeded in generating iPS cells. The cells had the properties of embryonic stem cells but were produced by inserting four specific genes into the nuclei of mouse adult fibroblasts (connective-tissue cells). The following year Yamanaka reported that he had derived iPS cells from human adult fibroblasts—the first successful attempt at generating human versions of these cells. This discovery marked a turning point in stem-cell research, because it offered a way of obtaining human stem cells without the controversial use of human embryos. Yamanaka’s technique to convert adult cells into iPS cells up to that time had employed a retrovirus that contained the c-Myc gene. This gene was believed to play a fundamental role in reprogramming the nuclei of adult cells. However, Yamanaka recognized that the activation of c-Myc during the process of creating iPS cells led to the formation of tumours when the stem cells were later transplanted into mice. He subsequently created iPS cells without c-Myc in order to render the cells noncancerous and thereby overcome a major concern in the therapeutic safety of iPS cells. In 2008 Yamanaka reported another breakthrough—the generation of iPS cells from mouse liver and stomach cells.

Yamanaka received multiple awards for his contributions to stem-cell research, including the Robert Koch Prize (2008), the Shaw Prize in Life Science and Medicine (2008), the Gairdner Foundation International Award (2009), the Albert Lasker Basic Medical Research Award (2009), and the Millennium Technology Prize (2012).

Details

Shinya Yamanaka (Yamanaka Shin'ya, born September 4, 1962) is a Japanese stem cell researcher and a Nobel Prize laureate. He is a professor and the director emeritus of Center for iPS Cell (induced Pluripotent Stem Cell) Research and Application, Kyoto University;[6] as a senior investigator at the UCSF-affiliated Gladstone Institutes in San Francisco, California; and as a professor of anatomy at University of California, San Francisco (UCSF). Yamanaka is also a past president of the International Society for Stem Cell Research (ISSCR).

He received the 2010 BBVA Foundation Frontiers of Knowledge Award in the biomedicine category, the 2011 Wolf Prize in Medicine with Rudolf Jaenisch, and the 2012 Millennium Technology Prize together with Linus Torvalds. In 2012, he and John Gurdon were awarded the Nobel Prize for Physiology or Medicine for the discovery that mature cells can be converted to stem cells.[8] In 2013, he was awarded the $3 million Breakthrough Prize in Life Sciences for his work.

Education

Yamanaka was born in Higashiōsaka, Japan, in 1962. After graduating from Tennōji High School attached to Osaka Kyoiku University, he received his M.D. degree at Kobe University in 1987 and his Ph.D. degree at Osaka City University, Graduate School of Medicine in 1993. After this, he went through a residency in orthopedic surgery at National Osaka Hospital and a postdoctoral fellowship at the Gladstone Institute of Cardiovascular disease, San Francisco.

Afterwards, he worked at the Gladstone Institutes in San Francisco, US, and Nara Institute of Science and Technology in Japan. Yamanaka is currently a professor and the director emeritus of Center for iPS Research and Application (CiRA), Kyoto University.[6] He is also a senior investigator at the Gladstone Institutes.

Professional career

Between 1987 and 1989, Yamanaka was a resident in orthopedic surgery at the National Osaka Hospital. His first operation was to remove a benign tumor from his friend Shuichi Hirata, a task he could not complete after one hour when a skilled surgeon would have taken ten minutes or so. Some seniors referred to him as "Jamanaka", a pun on the Japanese word for obstacle.

From 1993 to 1996, he was at the Gladstone Institute of Cardiovascular disease. Between 1996 and 1999, he was an assistant professor at Osaka City University Medical School, but found himself mostly looking after mice in the laboratory, not doing actual research.

His wife advised him to become a practicing doctor, but instead he applied for a position at the Nara Institute of Science and Technology. He stated that he could and would clarify the characteristics of embryonic stem cells, and this can-do attitude won him the job. From 1999 to 2003, he was an associate professor there, and started the research that would later win him the 2012 Nobel Prize. He became a full professor and remained at the institute in that position from 2003 to 2005. Between 2004 and 2010, Yamanaka was a professor at the Institute for Frontier Medical Sciences, Kyoto University. Between 2010 and 2022, Yamanaka was the director and a professor at the center for iPS Cell Research and Application (CiRA), Kyoto University. In April 2022, he stepped down and took place of the director emeritus of CiRA keeping with professor position.

In 2006, he and his team generated induced pluripotent stem cells (iPS cells) from adult mouse fibroblasts. iPS cells closely resemble embryonic stem cells, the in vitro equivalent of the part of the blastocyst (the embryo a few days after fertilization) which grows to become the embryo proper. They could show that his iPS cells were pluripotent, i.e. capable of generating all cell lineages of the body. Later he and his team generated iPS cells from human adult fibroblasts, again as the first group to do so. A key difference from previous attempts by the field was his team's use of multiple transcription factors, instead of transfecting one transcription factor per experiment. They started with 24 transcription factors known to be important in the early embryo, but could in the end reduce it to four transcription factors – Sox2, Oct4, Klf4 and c-Myc.

Yamanaka's Nobel Prize–winning research in iPS cells

The 2012 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine was awarded jointly to Sir John B. Gurdon and Shinya Yamanaka "for the discovery that mature cells can be reprogrammed to become pluripotent."

It appears to me that if one wants to make progress in mathematics, one should study the masters and not the pupils. - Niels Henrik Abel.

Nothing is better than reading and gaining more and more knowledge - Stephen William Hawking.

Offline

#1681 2025-01-24 16:17:41

- Jai Ganesh

- Administrator

- Registered: 2005-06-28

- Posts: 53,367

Re: crème de la crème

2144) François Englert

Gist:

Life

François Englert was born in Etterbeek, Belgium. His family was of Jewish origin and during the German occupation of Belgium during World War II, Englert concealed his Jewish roots and hid at different orphanages. He was first educated as an electrical-mechanical engineer and later received his Ph.D. in physics in 1959 from the Université Libre de Bruxelles. After spending two years at Cornell University in the U.S., Englert returned to Université Libre de Bruxelles, where he has continued his work. François Englert is married with five children.

Work

According to modern physics, matter consists of a set of particles that act as building blocks. Between these particles lie forces that are mediated by another set of particles. A fundamental property of the majority of particles is that they have a mass. Independently of one another, in 1964 both Peter Higgs and the team of François Englert and Robert Brout proposed a theory about the existence of a particle that explains why other particles have a mass. In 2012, two experiments conducted at the CERN laboratory confirmed the existence of the Higgs particle.

Summary

François Englert (born November 6, 1932, Etterbeek, Belgium) is a Belgian physicist who was awarded the 2013 Nobel Prize for Physics for proposing the existence of the Higgs field, which endows all elementary particles with mass through its interactions with them. He shared the prize with British physicist Peter Higgs, who hypothesized that the field had a carrier particle, later called the Higgs boson.

Englert received degrees in electromechanical engineering (1955) and physics (1958) from the Université Libre de Bruxelles (Free University of Brussels; ULB) before receiving a doctorate in physics from ULB in 1959. He was a research associate (1959–60) and an assistant professor (1960–61) in physics at Cornell University in Ithaca, New York. There he began a collaboration with Belgian physicist Robert Brout. Englert returned to ULB in 1961, becoming a professor there in 1964. With Brout he was codirector of the theoretical physics group at ULB from 1980 to 1998, when he became a professor emeritus. He also held visiting professorships at Tel Aviv University from 1984 and at Chapman University in Orange, California, from 2011.

In 1964 Englert and Brout wrote a paper, “Broken Symmetry and the Mass of Gauge Vector Mesons,” describing how particles can acquire mass through the interaction with a field that has a nonzero value (later called the Higgs mechanism). That same year Higgs later wrote two papers, one of which mentioned the existence of a boson associated with the field, and American physicists Gerald Guralnik and Carl Hagen and British physicist Tom Kibble also independently discovered the Higgs mechanism.

The ideas of these physicists were later incorporated into what became known as electroweak theory to describe the origin of particle masses. After the discovery of the W and Z particles in 1983, the only remaining part of electroweak theory that needed confirmation was the Higgs field and its boson. Particle physicists searched for the particle for decades, and in July 2012 scientists at the Large Hadron Collider at CERN announced, with Englert and Higgs in attendance, that they had detected an interesting signal that was likely from a Higgs boson with a mass of 125–126 giga-electron volts (GeV; billion electron volts). Definitive confirmation that the particle was the Higgs boson was announced in March 2013.

Englert received many honours for his work, including the Wolf Prize in physics (2004, shared with Brout and Higgs) and the J.J. Sakurai Prize (2010, shared with Brout, Higgs, Guralnik, Hagen, and Kibble).

Details

François, Baron Englert (born 6 November 1932) is a Belgian theoretical physicist and 2013 Nobel Prize laureate.

Englert is professor emeritus at the Université libre de Bruxelles (ULB), where he is a member of the Service de Physique Théorique. He is also a Sackler Professor by Special Appointment in the School of Physics and Astronomy at Tel Aviv University and a member of the Institute for Quantum Studies at Chapman University in California. He was awarded the 2010 J. J. Sakurai Prize for Theoretical Particle Physics (with Gerry Guralnik, C. R. Hagen, Tom Kibble, Peter Higgs, and Robert Brout), the Wolf Prize in Physics in 2004 (with Brout and Higgs) and the High Energy and Particle Prize of the European Physical Society (with Brout and Higgs) in 1997 for the mechanism which unifies short and long range interactions by generating massive gauge vector bosons.

Englert has made contributions in statistical physics, quantum field theory, cosmology, string theory and supergravity. He is the recipient of the 2013 Prince of Asturias Award in technical and scientific research, together with Peter Higgs and CERN.

Englert was awarded the 2013 Nobel Prize in Physics, together with Peter Higgs for the discovery of the Brout–Englert–Higgs mechanism.

Early life

François Englert is a Holocaust survivor. He was born in a Belgian Jewish family. During the German occupation of Belgium in World War II, he had to conceal his Jewish identity and live in orphanages and children's homes in the towns of Dinant, Lustin, Stoumont and, finally, Annevoie-Rouillon. These towns were eventually liberated by the US Army.

Academic career

He graduated as an electromechanical engineer in 1955 from the Free University of Brussels (ULB) where he received his PhD in physical sciences in 1959. From 1959 until 1961, he worked at Cornell University, first as a research associate of Robert Brout and then as assistant professor. He then returned to the ULB, where he became a university professor and was joined there by Robert Brout who, in 1980, with Englert coheaded the theoretical physics group. In 1998 Englert became professor emeritus. In 1984 Englert was first appointed as a Sackler Professor by Special Appointment in the School of Physics and Astronomy at Tel-Aviv University. Englert joined Chapman University's Institute for Quantum Studies in 2011, where he serves as a distinguished visiting professor.

Brout–Englert–Higgs–Guralnik–Hagen–Kibble mechanism

Brout and Englert showed in 1964 that gauge vector fields, abelian and non-abelian, could acquire mass if empty space were endowed with a particular type of structure that one encounters in material systems. Focusing on the failure of the Goldstone theorem for gauge fields, Higgs reached essentially the same result. A third paper on the subject was written later in the same year by Gerald Guralnik, C. R. Hagen, and Tom Kibble. The three papers written on this boson discovery by Higgs, Englert and Brout, and Guralnik, Hagen, Kibble were each recognized as milestone papers for this discovery by Physical Review Letters 50th anniversary celebration. While each of these famous papers took similar approaches, the contributions and differences between the 1964 PRL symmetry breaking papers is noteworthy.

To illustrate the structure, consider a ferromagnet which is composed of atoms each equipped with a tiny magnet. When these magnets are lined up, the inside of the ferromagnet bears a strong analogy to the way empty space can be structured. Gauge vector fields that are sensitive to this structure of empty space can only propagate over a finite distance. Thus, they mediate short range interactions and acquire mass. Those fields that are not sensitive to the structure propagate unhindered. They remain massless and are responsible for the long range interactions. In this way, the mechanism accommodates within a single unified theory both short and long-range interactions.

Brout and Englert, Higgs, and Gerald Guralnik, C. R. Hagen, and Tom Kibble introduced as agent of the vacuum structure a scalar field (most often called the Higgs field) which many physicists view as the agent responsible for the masses of fundamental particles. Brout and Englert also showed that the mechanism may remain valid if the scalar field is replaced by a more structured agent such as a fermion condensate. Their approach led them to conjecture that the theory is renormalizable. The eventual proof of renormalizability, a major achievement of twentieth century physics, is due to Gerardus 't Hooft and Martinus Veltman who were awarded the 1999 Nobel Prize for this work. The Brout–Englert–Higgs–Guralnik–Hagen–Kibble mechanism is the building stone of the electroweak theory of elementary particles and laid the foundation of a unified view of the basic laws of nature.

It appears to me that if one wants to make progress in mathematics, one should study the masters and not the pupils. - Niels Henrik Abel.

Nothing is better than reading and gaining more and more knowledge - Stephen William Hawking.

Offline

#1682 2025-01-25 16:07:06

- Jai Ganesh

- Administrator

- Registered: 2005-06-28

- Posts: 53,367

Re: crème de la crème

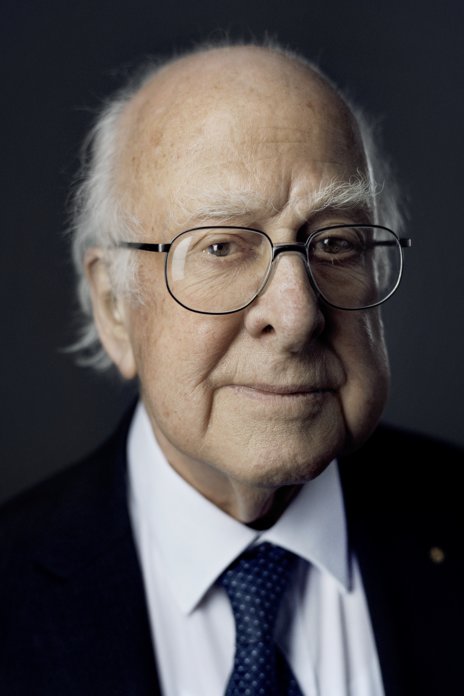

2145) Peter Higgs

Gist:

Life

Peter Higgs was born in Newcastle upon Tyne in the UK, to a Scottish mother and an English father who worked as a sound engineer at the BBC. Because he suffered from asthma, Higgs received part of his early education at his home in Bristol before moving to London to study math and physics at age 17. Higgs received his Ph.D. from King's College in 1954. He then moved to the University of Edinburgh, where he has remained, with the exception of a few years spent in London in the late 1950s. Peter Higgs has two sons.

Work

According to modern physics, matter consists of a set of particles that act as building blocks. Between these particles lie forces that are mediated by another set of particles. A fundamental property of the majority of particles is that they have a mass. Independently of one another, in 1964 both Peter Higgs and the team of François Englert and Robert Brout proposed a theory about the existence of a particle that explains why other particles have a mass. In 2012, two experiments conducted at the CERN laboratory confirmed the existence of the Higgs particle.

Summary

Peter Higgs (born May 29, 1929, Newcastle upon Tyne, Northumberland, England—died April 8, 2024, Edinburgh, Scotland) was a British physicist who was awarded the 2013 Nobel Prize for Physics for proposing the existence of the Higgs boson, a subatomic particle that is the carrier particle of a field that endows all elementary particles with mass through its interactions with them. He shared the prize with Belgian physicist François Englert.

Higgs received a bachelor’s degree (1950), master’s degree (1951), and doctorate (1954) in physics from King’s College, University of London. He was a research fellow (1955–56) at the University of Edinburgh and then a research fellow (1956–58) and lecturer (1959–60) at the University of London. He became a lecturer in mathematical physics at Edinburgh in 1960 and spent the remainder of his career there, becoming a reader in mathematical physics (1970–80) and a professor of theoretical physics (1980–96). He retired in 1996.

Higgs’s earliest work was in molecular physics and concerned calculating the vibrational spectra of molecules. In 1956 he began working in quantum field theory. He wrote two papers in 1964 describing what later became known as the Higgs mechanism, in which a scalar field (that is, a field present at all points in space) gives particles mass. To Higgs’s surprise, the journal to which he submitted the second paper rejected it. When Higgs revised the paper, he made the significant addition that his theory predicted the existence of a heavy boson. (The Higgs mechanism was independently discovered in 1964 by Englert and Belgian physicist Robert Brout and by another group consisting of American physicists Gerald Guralnik and Carl Hagen and British physicist Tom Kibble. However, neither group mentioned the possibility of a massive boson.)

In the late 1960s American physicist Steven Weinberg and Pakistani physicist Abdus Salam independently incorporated Higgs’s ideas into what later became known as electroweak theory to describe the origin of particle masses. After the discovery of the W and Z particles in 1983, the only remaining part of electroweak theory that needed confirmation was the Higgs field and its boson. Particle physicists searched for the particle for decades, and in July 2012 scientists at the Large Hadron Collider at CERN announced, with Higgs in attendance, that they had detected an interesting signal that was likely from a Higgs boson with a mass of 125–126 gigaelectron volts (billion electron volts; GeV). Definitive confirmation that the particle was the Higgs boson was announced in March 2013.

Higgs became a fellow of the Royal Society in 1983. He received many honours for his work, including the Wolf Prize in physics (2004, shared with Brout and Englert), the J.J. Sakurai Prize (2010, shared with Brout, Englert, Guralnik, Hagen, and Kibble), and the Copley Medal of the Royal Society (2015).

Details

Peter Ware Higgs (29 May 1929 – 8 April 2024) was a British theoretical physicist, professor at the University of Edinburgh,[7][8] and Nobel laureate in Physics for his work on the mass of subatomic particles.

In 1964, Higgs was the single author of one of the three milestone papers published in Physical Review Letters (PRL) that proposed that spontaneous symmetry breaking in electroweak theory could explain the origin of mass of elementary particles in general and of the W and Z bosons in particular. This Higgs mechanism predicted the existence of a new particle, the Higgs boson, the detection of which became one of the great goals of physics. In 2012, CERN announced the discovery of the Higgs boson at the Large Hadron Collider. The Higgs mechanism is generally accepted as an important ingredient in the Standard Model of particle physics, without which certain particles would have no mass.

For this work, Higgs received the Nobel Prize in Physics, which he shared with François Englert in 2013.

Early life and education

Higgs was born in the Elswick district of Newcastle upon Tyne, England, to Thomas Ware Higgs (1898–1962) and his wife Gertrude Maude née Coghill (1895–1969). His father worked as a sound engineer for the BBC, and as a result of childhood asthma, together with the family moving around because of his father's job and later World War II, Higgs missed some early schooling and was taught at home. When his father relocated to Bedford, Higgs stayed behind in Bristol with his mother, and was largely raised there. He attended Cotham Grammar School in Bristol from 1941 to 1946, where he was inspired by the work of one of the school's alumni, Paul Dirac, a founder of the field of quantum mechanics.

In 1946, at the age of 17, Higgs moved to City of London School, where he specialised in mathematics, then in 1947 to King's College London, where he graduated with a first-class honours degree in physics in 1950 and achieved a master's degree in 1952. He was awarded an 1851 Research Fellowship from the Royal Commission for the Exhibition of 1851, and performed his doctoral research in molecular physics under the supervision of Charles Coulson and Christopher Longuet-Higgins. He was awarded a PhD degree in 1954 with a thesis entitled Some problems in the theory of molecular vibrations from the university.

Career and research

After finishing his doctorate, Higgs was appointed a Senior Research Fellow at the University of Edinburgh (1954–56). He then held various posts at Imperial College London, and University College London (where he also became a temporary lecturer in mathematics). He returned to the University of Edinburgh in 1960 to take up the post of Lecturer at the Tait Institute of Mathematical Physics, allowing him to settle in the city he had enjoyed while hitchhiking to the Western Highlands as a student in 1949. He was promoted to Reader, became a Fellow of the Royal Society of Edinburgh (FRSE) in 1974 and was promoted to a personal chair of Theoretical Physics in 1980. On his retirement in 1996, he became an emeritus professor.

Higgs was elected Fellow of the Royal Society (FRS) in 1983 and Fellow of the Institute of Physics (FInstP) in 1991. He was awarded the Rutherford Medal and Prize in 1984. He received an honorary degree from the University of Bristol in 1997. In 2008, he received an Honorary Fellowship from Swansea University for his work in particle physics.[28] At Edinburgh, Higgs first became interested in mass, developing the idea that particles – massless when the universe began – acquired mass a fraction of a second later as a result of interacting with a theoretical field (which became known as the Higgs field). Higgs postulated that this field permeates space, giving mass to all elementary subatomic particles interacting with it.

The Higgs mechanism postulates the existence of the Higgs field, which confers mass on quarks and leptons; this causes only a tiny portion of the masses of other subatomic particles, such as protons and neutrons. In these, gluons that bind quarks together confer most of the particle mass. The original basis of Higgs's work came from the Japanese-born theorist and Nobel Prize laureate Yoichiro Nambu from the University of Chicago. Nambu had proposed a theory known as spontaneous symmetry breaking based on what was known to happen in superconductivity in condensed matter, which incorrectly predicted massless particles (the Goldstone's theorem).

Higgs reportedly developed the fundamentals of his theory after returning to his Edinburgh New Town apartment from a failed weekend camping trip to the Highlands. He stated that there was no "eureka moment" in the development of the theory. He wrote a short paper exploiting a loophole in Goldstone's theorem (massless Goldstone particles need not occur when local symmetry is spontaneously broken in a relativistic theory[35]) and published it in Physics Letters, a European physics journal edited at CERN, in Switzerland, in 1964.

Higgs wrote a second paper describing a theoretical model (the Higgs mechanism), but the paper was rejected (the editors of Physics Letters judged it "of no obvious relevance to physics"). Higgs wrote an extra paragraph and sent his paper to Physical Review Letters, another leading physics journal, which published it later in 1964. This paper predicted a new massive spin-zero boson (later named the Higgs boson). Other physicists, Robert Brout and François Englert and Gerald Guralnik, C. R. Hagen and Tom Kibble had reached similar conclusions at about the same time. In the published version, Higgs quotes Brout and Englert, and the third paper quotes the previous ones. The three papers written on this boson discovery by Higgs, Guralnik, Hagen, Kibble, Brout, and Englert were each recognised as milestone papers by Physical Review Letters 50th-anniversary celebration. While each of these famous papers took similar approaches, the contributions and differences between the 1964 PRL symmetry breaking papers are noteworthy. The mechanism had been proposed in 1962 by Philip Anderson although he did not include a crucial relativistic model.

On 4 July 2012, CERN announced the ATLAS and Compact Muon Solenoid (CMS) experiments had seen strong indications for the presence of a new particle, which could be the Higgs boson, in the mass region around 126 gigaelectronvolts (GeV). Speaking at the seminar in Geneva, Higgs commented "It's really an incredible thing that it's happened in my lifetime." Ironically, this probable confirmation of the Higgs boson was made at the same place where the editor of Physics Letters rejected Higgs's paper.

Awards and honours

Higgs was honoured with several awards in recognition of his work, including the 1981 Hughes Medal from the Royal Society; the 1984 Rutherford Medal from the Institute of Physics; the 1997 Dirac Medal and Prize for outstanding contributions to theoretical physics from the Institute of Physics; the 1997 High Energy and Particle Physics Prize by the European Physical Society; the 2004 Wolf Prize in Physics; the 2009 Oskar Klein Memorial Lecture medal from the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences; the 2010 American Physical Society J. J. Sakurai Prize for Theoretical Particle Physics; a unique Higgs Medal from the Royal Society of Edinburgh in 2012; and the Royal Society awarded him the 2015 Copley Medal, the world's oldest scientific prize.

It appears to me that if one wants to make progress in mathematics, one should study the masters and not the pupils. - Niels Henrik Abel.

Nothing is better than reading and gaining more and more knowledge - Stephen William Hawking.

Offline

#1683 2025-01-26 15:30:12

- Jai Ganesh

- Administrator

- Registered: 2005-06-28

- Posts: 53,367

Re: crème de la crème

2146) Martin Karplus

Gist:

Life

Martin Karplus was born in Vienna, Austria. His family fled to the U.S. prior to the German occupation in 1938. After studying at Harvard College in Cambridge, Massachusetts in the United States, Karplus moved to the California Institute of Technology, Pasadena, where he received his Ph.D. in 1953. He worked at the University of Illinois in Urbana-Champaign, at Columbia University in New York, and later at Harvard University from 1967. He is also associated with the University of Strasbourg, France. Martin Karplus is married with three children.

Work

The world around us is made up of atoms that are joined together to form molecules. During chemical reactions atoms change places and new molecules are formed. To accurately predict the course of the reactions at the sites where the reaction occurs advanced calculations based on quantum mechanics are required. For other parts of the molecules, it is possible to use the less complicated calculations of classical mechanics. In the 1970s, Martin Karplus, Michael Levitt, and Arieh Warshel successfully developed methods that combined quantum and classical mechanics to calculate the courses of chemical reactions using computers.

Summary

Martin Karplus (born March 15, 1930, Vienna, Austria—died December 28, 2024, Cambridge, Massachusetts, U.S.) was an American Austrian chemist who was awarded the 2013 Nobel Prize for Chemistry for developing accurate computer models of chemical reactions that were able to use features of both classical physics and quantum mechanics. He shared the prize with American-British-Israeli chemist Michael Levitt and American-Israeli chemist Arieh Warshel.

Karplus received a bachelor’s degree from Harvard University in Cambridge, Massachusetts, in 1951 and a doctorate from the California Institute of Technology in Pasadena in 1953. He was a postdoctoral fellow at the University of Oxford in England (1953–55) and a professor at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign (1955–60) and at Columbia University in New York City (1960–65). He joined the chemistry faculty at Harvard in 1966, eventually becoming professor emeritus. In 1996 he also became a professor at the Louis Pasteur University (later incorporated into the University of Strasbourg) in France.

In 1970, while at Harvard, Karplus was joined by Warshel, who was a postdoctoral fellow. Karplus had already worked on computer programs that used quantum mechanics in modeling chemical reactions, whereas Warshel had extensive experience with computer modeling of molecules using classical physics. They wrote a program that modeled the atomic nuclei and some electrons of a molecule using classical physics and other electrons using quantum mechanics. Their technique was initially limited to molecules with mirror symmetry. However, Karplus was particularly interested in modeling retinal, a large complex molecule found in the eye and crucial to vision, which changes shape when exposed to light. In 1974 Karplus, Warshel, and collaborators published a paper that successfully modeled retinal’s change in shape.

Karplus’s autobiography, Spinach on the Ceiling: The Multifaceted Life of a Theoretical Chemist, was published in 2020.

Details

Martin Karplus (March 15, 1930 – December 28, 2024) was an Austrian and American theoretical chemist. He was the Theodore William Richards Professor of Chemistry at Harvard University. He was also the director of the Biophysical Chemistry Laboratory, a joint laboratory between the French National Center for Scientific Research and the University of Strasbourg, France. Karplus received the 2013 Nobel Prize in Chemistry, together with Michael Levitt and Arieh Warshel, for "the development of multiscale models for complex chemical systems".

Early life

Martin Karplus was born on March 15, 1930, in Vienna, Austria. He was a child when his family fled from the Nazi-occupation in Austria a few days after the Anschluss in March 1938, spending several months in Zürich, Switzerland and La Baule, France before immigrating to the United States. Prior to their immigration to the United States, the family was known for being "an intellectual and successful secular Jewish family" in Vienna. His grandfather, Johann Paul Karplus (1866–1936) was a highly acclaimed professor of psychiatry at the University of Vienna. His great-aunt, Eugenie Goldstern, was an ethnologist who was killed during the Holocaust. He was the nephew, by marriage, of the sociologist, philosopher and musicologist Theodor W. Adorno and grandnephew of the physicist Robert von Lieben. His brother, Robert Karplus, was an internationally recognized physicist and educator at University of California, Berkeley. Continuing with the academic family theme, his nephew, Andrew Karplus, is a biochemistry and biophysics professor at Oregon State University.

Education

After earning an AB degree in Chemistry and Physics from Harvard College in 1951, Karplus pursued graduate studies at the California Institute of Technology. He completed his PhD in 1953 under Nobel laureate Linus Pauling. According to Pauling, Karplus "was [his] most brilliant student." He was an NSF Postdoctoral Fellow at the University of Oxford (1953–55) where he worked with Charles Coulson.

Teaching career

Karplus taught at the University of Illinois at Urbana–Champaign (1955–60) and then Columbia University (1960–65) before moving to join the Chemistry Department faculty at Harvard in 1966.

He was a professor at the Louis Pasteur University in 1996 where he established a research group in Strasbourg, France, after two sabbatical visits between 1992 and 1995 in the NMR laboratory of Jean-François Lefèvre. He has supervised more than 200 graduate students and postdoctoral researchers over his career since 1955.

Personal life and death

Karplus was married to Marci and had three children. He died at his home in Cambridge, Massachusetts, on December 28, 2024, at the age of 94.

Research

Karplus published his first academic paper when he was 17 years old. Karplus contributed to many fields in physical chemistry, including chemical dynamics, quantum chemistry, and most notably, molecular dynamics simulations of biological macromolecules. He has also been influential in nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy, particularly to the understanding of nuclear spin-spin coupling and electron spin resonance spectroscopy. The Karplus equation describing the correlation between coupling constants and dihedral angles in proton nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy is named after him.

From 1969 to 1970, Karplus visited the Structural Studies Division at the MRC Laboratory of Molecular Biology.

In 1970 postdoctoral fellow Arieh Warshel joined Karplus at Harvard. Together they wrote a computer program that modeled the atomic nuclei and some electrons of a molecule using classical physics and modeling other electrons using quantum mechanics. In 1974 Karplus, Warshel and other collaborators published a paper based on this type of modeling, which successfully modeled the change in shape of retinal, a large complex protein molecule important to vision.

His research was concerned primarily with the properties of molecules of biological interest. His group originated and coordinated the development of the CHARMM program for molecular dynamics simulations.

It appears to me that if one wants to make progress in mathematics, one should study the masters and not the pupils. - Niels Henrik Abel.

Nothing is better than reading and gaining more and more knowledge - Stephen William Hawking.

Offline

#1684 2025-01-27 16:20:51

- Jai Ganesh

- Administrator

- Registered: 2005-06-28

- Posts: 53,367

Re: crème de la crème

2147) Michael Levitt (biophysicist)

Gist:

Life

Michael Levitt was born in Pretoria, South Africa, to a Jewish family from Lithuania. He studied first at the University of Pretoria and later at King's College, London. After a period spent at the Weizmann Institute of Science in Rehovot, Israel, Levitt continued his postgraduate studies at the Laboratory of Molecular Biology in Cambridge, England, where he continued working until he returned to the Weizmann Institute in 1980. Since 1987, he has worked at Stanford University. Michael Levitt is married with three children.

Work

The world around us is made up of atoms that are joined together to form molecules. During chemical reactions atoms change places and new molecules are formed. To accurately predict the course of the reactions at the sites where the reaction occurs advanced calculations based on quantum mechanics are required. For other parts of the molecules, it is possible to use the less complicated calculations of classical mechanics. In the 1970s, Michael Levitt, Martin Karplus, and Arieh Warshel successfully developed methods that combined quantum and classical mechanics to calculate the courses of chemical reactions using computers.

Summary

Michael Levitt (born May 9, 1947, Pretoria, South Africa) is an American British Israeli chemist who was awarded the 2013 Nobel Prize for Chemistry for developing accurate computer models of chemical reactions that were able to use features of both classical physics and quantum mechanics. He shared the prize with American-Austrian chemist Martin Karplus and American-Israeli chemist Arieh Warshel.

Levitt received a bachelor’s degree in physics (1967) from King’s College in London. He worked as a visiting fellow at the Weizmann Institute of Science in Reḥovot, Israel, from 1967 to 1968. He received a doctorate in biophysics jointly granted by the Medical Research Council (MRC) Laboratory of Molecular Biology in Cambridge, England, and the University of Cambridge in 1971. He was a postdoctoral fellow at the Weizmann Institute from 1972 to 1974 and a staff scientist at the MRC Laboratory from 1974 to 1979. He became an associate professor in chemical physics at the Weizmann Institute in 1979 and left there as a full professor in 1987. Afterward he became a professor of structural biology at Stanford University in California.

During Levitt’s time as a visiting fellow at the Weizmann Institute, he worked with Warshel (then a graduate student) on computer modeling of molecules using classical physics. In 1972 Levitt reunited with Warshel at the Weizmann Institute and later at the MRC Laboratory. In 1975 they published results of a simulation of protein folding. They had long been interested in reactions involving enzymes, and they constructed a scheme in which they accounted for the interaction between those parts of the enzyme that were modeled classically and those modeled quantum mechanically. They also had to account for the interaction of both parts with the surrounding medium. In 1976 they published a paper that applied their general scheme to the first computer model of an enzymatic reaction. More significantly, their scheme could be used to model any molecule.

Details

Michael Levitt, (born 9 May 1947) is a South African-born biophysicist and a professor of structural biology at Stanford University, a position he has held since 1987. Levitt received the 2013 Nobel Prize in Chemistry, together with Martin Karplus and Arieh Warshel, for "the development of multiscale models for complex chemical systems". In 2018, Levitt was a founding co-editor of the Annual Review of Biomedical Data Science.

Early life and education

Michael Levitt was born in Pretoria, South Africa, to a Jewish family from Plungė, Lithuania; his father was from Lithuania and his mother from the Czech Republic. He attended Sunnyside Primary School and then Pretoria Boys High School between 1960 and 1962. The family moved to England when he was 15. Levitt spent 1963 studying applied mathematics at the University of Pretoria. He attended King's College London, graduating with a first-class honours degree in physics in 1967.

In 1967, he visited Israel for the first time. Together with his Israeli wife, Rina, a multimedia artist, he left to study at Cambridge, where their three children were born. Levitt was a PhD student in Computational biology at Peterhouse, Cambridge, and was based at the Laboratory of Molecular Biology from 1968 to 1972, where he developed a computer program for studying the conformations of molecules that underpinned much of his later work.

Career and research

In 1979, he returned to Israel and conducted research at the Weizmann Institute of Science in Rehovot, becoming an Israeli citizen in 1980. He served in the Israel Defense Forces for six weeks in 1985. In 1986, he began teaching at Stanford University, and since then has split his time between Israel and California. He went on to gain a research fellowship at Gonville and Caius College, Cambridge.

From 1980 to 1987, he was Professor of Chemical Physics at the Weizmann Institute of Science, Rehovot. Thereafter, he served as Professor of Structural biology, at Stanford University, California.

* Royal Society Exchange Fellow, Weizmann Institute, Israel, 1967–68

* Staff Scientist, MRC Laboratory of Molecular Biology, Cambridge, 1973–80

* Professor of Chemical Physics, Weizmann Institute, 1980–87 (dept. chair 1980–83)

* Professor of Structural Biology, Stanford University, 1987–present

Levitt was one of the first researchers to conduct molecular dynamics simulations of DNA and proteins and developed the first software for this purpose. He is currently well known for developing approaches to predict macromolecular structures, having participated in many Critical Assessment of Techniques for Protein Structure Prediction (CASP) competitions, where he criticised molecular dynamics for inability to refine protein structures. He has also worked on simplified representations of protein structure for analysing folding and packing, as well as developing scoring systems for large-scale sequence-structure comparisons. He has mentored many successful scientists, including Mark Gerstein and Ram Samudrala. Cyrus Chothia was one of his colleagues.

Industrial collaboration

Levitt has served on the Scientific Advisory Boards of the following companies: Dupont Merck Pharmaceuticals, AMGEN, Protein Design Labs, Affymetrix, Molecular Applications Group, 3D Pharmaceuticals, Algodign, Oplon Ltd, Cocrystal Discovery, InterX, and StemRad, Ltd,.

COVID-19

Levitt has been outspoken during the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic, and made a number of wrong predictions on the disease's spread based on his own modelling. On March 18, 2020, he predicted that Israel would see less than ten deaths from COVID-19, and on July 25, 2020, he incorrectly predicted that the outbreak in the U.S. would be over by the end of August 2020 with a total of fewer than 170,000 deaths. As of November 2021, the U.S. was recording COVID-19 deaths at the rate of about 1,000 per day, while Israel has reported over 8,000 COVID-19 deaths since the start of the pandemic.

Levitt has also raised concerns about potential damaging effects of COVID-19 lockdown orders on economic activity as well in increasing suicide and abuse rates, and has signed the Great Barrington Declaration, a statement supported by a group of academics advocating for alternatives to lockdowns which has been criticized by the WHO and other public health organizations as dangerous and lacking in sound scientific basis.