Math Is Fun Forum

You are not logged in.

- Topics: Active | Unanswered

Pages: 1

#1 2024-01-03 00:02:59

- Jai Ganesh

- Administrator

- Registered: 2005-06-28

- Posts: 53,247

Mastication

Mastication

Gist

Mastication is the technical word for chewing. It is the first step in digestion, in which food is broken into smaller pieces using the teeth. Grinding food increases its surface area. This allows for more efficient digestion and optimal nutrient extraction.

Mastication is the first step in digestion. Chewing food increases its surface area and allows for better digestion.

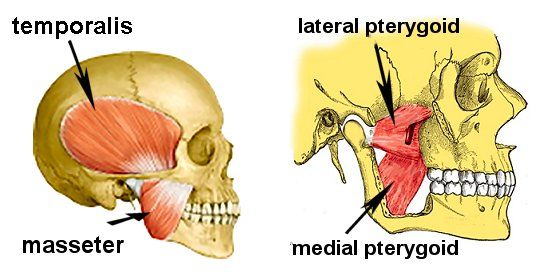

Chewing requires teeth, the maxilla and mandible bones, the lips, the cheeks, and the masseter, temporalis, medial pterygoid, and lateral pterygoid muscles.

While mastication is most often associated with digestion, it also serves another function. Chewing stimulates the hippocampus, supporting learning and memory formation.

Mastication Process

Digestion begins when food enters the mouth. However, not all food requires mastication. For example, you don't need to chew gelatin or ice cream. In addition to liquids and gels, researchers have found fish, eggs, cheese, and grains may be digested without chewing. Vegetables and meat are not properly digested unless they are ground.

Mastication may be voluntarily controlled, but it is normally a semi-automatic or unconscious activity. Proprioceptive nerves (those that sense the position of objects) in the joints and teeth determine how long and forcefully chewing occurs. The tongue and cheeks position food, while the jaws bring the teeth into contact and then apart. Chewing stimulates saliva production. As food is moved around the mouth, saliva warms, moistens it, and lubricates it and begins digestion of carbohydrates (sugars and starches). The chewed food, which is called a bolus, is then swallowed. It continues digestion by moving through the esophagus into the stomach and intestines.

In ruminants, such as cattle and giraffes, mastication occurs more than once. The chewed food is called cud. The animal swallows the bolus, which is then regurgitated back into the mouth to be chewed again. Chewing the cud allows a ruminant to extract nutrition from plant cellulose, which is normally not digestible. The reticulorumen of ruminants (first chamber of the alimentary canal) contains microbes that are able to degrade cellulose.

Summary

Chewing or mastication is the process by which food is crushed and ground by teeth. It is the first step of digestion, and it increases the surface area of foods to allow a more efficient break down by enzymes.

During the mastication process, the food is positioned by the cheek and tongue between the teeth for grinding. The muscles of mastication move the jaws to bring the teeth into intermittent contact, repeatedly occluding and opening. As chewing continues, the food is made softer and warmer, and the enzymes in saliva begin to break down carbohydrates in the food. After chewing, the food (now called a bolus) is swallowed. It enters the esophagus and via peristalsis continues on to the stomach, where the next step of digestion occurs. Increasing the number of chews per bite increases relevant gut hormones. Studies suggest that chewing may decrease self-reported hunger and food intake. Chewing gum has been around for many centuries; there is evidence that northern Europeans chewed birch bark tar 9,000 years ago.

Chewing, needing specialized teeth, is mostly a mammalian adaptation that appeared in early Synapsids, though some later herbivorous dinosaurs, since extinct, had developed chewing too. Nowadays, only mammals chew in the strict sense of the word, though some fishes have a somewhat similar behavior. Neither birds, nor amphibians or any living reptiles chew.

Premastication is sometimes performed by human parents for infants who are unable to do so for themselves. The food is masticated in the mouth of the parent into a bolus and then transferred to the infant for consumption (some other animals also premasticate).

Cattle and some other animals, called ruminants, chew food more than once to extract more nutrients. After the first round of chewing, this food is called cud.

Details:

Mastication Definition

Mastication is the mechanical grinding of food into smaller pieces by teeth; it is essentially a technical word for “chewing”. Mastication breaks down food so that it can go through the esophagus to the stomach. Breaking down food into smaller pieces also increases its surface area so that digestive enzymes can continue to break it down more efficiently. Muscles involved in mastication include the masseter, temporalis, medial pterygoid, and lateral pterygoid.

Function of Mastication

Mastication is step one of the digestion process. It breaks down food into smaller pieces so that it can be further digested by enzymes. Many different bones, such as the teeth and mandible (jaw bone), and muscles like the tongue and jaw muscles all work together to enable a person to chew food. Mastication should not be confused with maceration, which is the breaking down of food into chyme in the stomach.

Chewing originated with the evolution of herbivory in animals. Those animals that ate plants needed to grind them up before swallowing, and flat teeth such as molars were most efficient for masticating plant material. Carnivores, which have pointy canine teeth, do very little chewing of their food, sometimes even eating it whole. Humans are omnivores; we eat both plants and animals. This is reflected by the variety of shapes of our teeth. We have both molars and canine teeth in addition to premolars and incisors (front teeth).

Muscles of Mastication:

Masseter

The masseter muscles are powerful muscles that are located in the cheek area. There is one on either side of the face, so the two muscles are called the left and right masseter muscles. The function of the masseter muscles is to raise the lower jaw by elevating the mandible during chewing. Herbivorous animals have large, strong masseter muscles since they have to do a lot of chewing.

Temporalis

The temporalis (also called temporal) muscle is a large, semi-circle-shaped muscle that reaches from the molars to the temples and curls back around to the approximate location of the ear. It is the strongest muscle in the temporomandibular (jaw) joint. The anterior, or front, part of the muscle helps close the mouth, while the posterior, or back, part of the muscle moves the jaw backward in a movement known as retrusion.

Medial Pterygoid

The medial pterygoid muscle is a thick muscle that is located from the back of the molars to just under eye level (it is located behind the orbits). It has many functions including closing the jaw, moving the jaw back to the middle if excursion (side-to-side movement) has occurred, and aiding in protrusion of the mandible, which is when the jaw moves forward.

Lateral Pterygoid

The lateral pterygoid muscle is located above the medial pterygoid. It can lower the jaw and move the jaw from side to side (excursion). It also helps move the jaw forward. It is the only muscle involved with mastication that opens the jaw; all the others help close the jaw.

The Masticatory Cycle

The masticatory cycle is the pathway that the mandible takes while chewing food. During the opening phase, the mandible is depressed, which means that is opened; it is lowered to create space to take in food. During the closing phase, the jaw closes. This action is performed mainly by the masseter, temporalis, and medial pterygoid muscles. The third phase is the occlusal phase. During this phase, the teeth make contact with one another and the chewing motion is completed. Then the cycle begins again, with the jaw opening and closing and the teeth occluding until the food has been chewed enough to swallow.

The Temporomandibular Joint

The temporomandibular joint, or TMJ, is the jaw joint. It is named for the temporal bone and the mandible, which are two bones that articulate at this joint. The mandible is moved by the four muscles of mastication, while the temporal bone remains in one place; in other words, mastication is accomplished by moving only the lower jaw.

Experiencing pain, limited movement, and popping noises when opening the mouth is called temporomandibular joint dysfunction (TMD). It is relatively common, affecting 20-30% of the adult population worldwide; it also affects more women than men. Other symptoms include headache, a feeling of pressure on the jaw, and dizziness. Often, TMD can become chronic. It can be treated with medication, eating soft foods, physical therapy, and even cognitive-behavioral therapy to reduce stress since stress can exacerbate symptoms. Extreme measures such as surgery are avoided since they are invasive and cannot be easily reversed if problems occur.

Mastication Motor Program

Mastication is performed mostly unconsciously; we do not have to think about the movements of muscles, the TMJ and the tongue when chewing food. The way our brains organize a series of movements is called a motor program. The actions of mastication are thought to be one such motor program controlled by the central nervous system. Chewing and swallowing are largely unconscious, but we do learn to adjust the way we chew based on the type of food consumed (e.g. hard, soft) or the way the teeth meet in the mouth when the jaw closes.

It appears to me that if one wants to make progress in mathematics, one should study the masters and not the pupils. - Niels Henrik Abel.

Nothing is better than reading and gaining more and more knowledge - Stephen William Hawking.

Offline

Pages: 1