Math Is Fun Forum

You are not logged in.

- Topics: Active | Unanswered

Pages: 1

#1 2025-08-26 21:42:13

- Jai Ganesh

- Administrator

- Registered: 2005-06-28

- Posts: 52,730

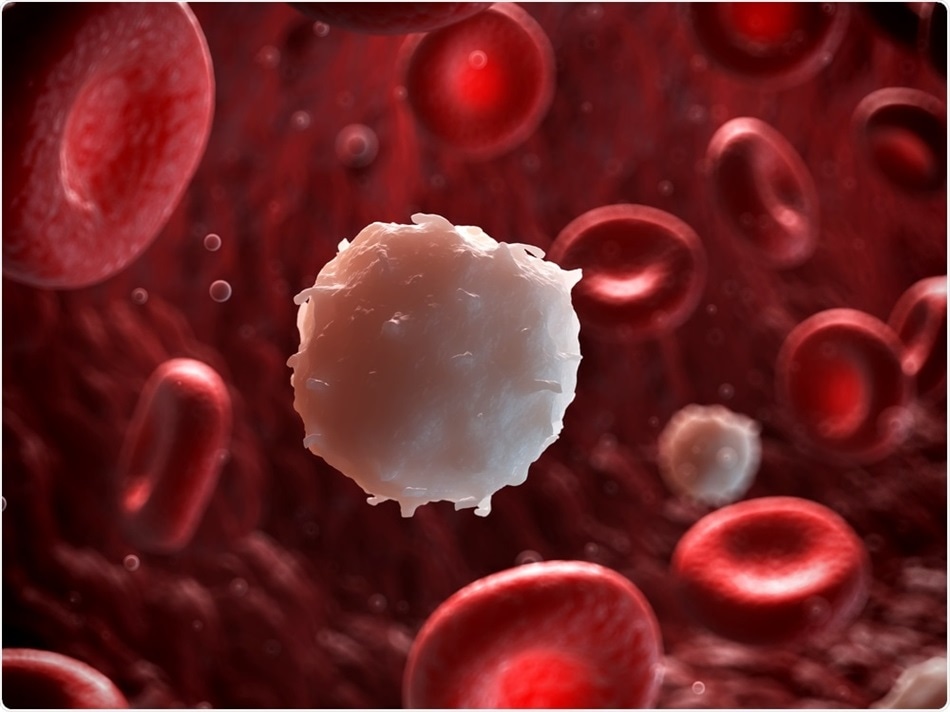

White Blood Cells

White Blood Cells

Gist

White Blood Cells are components of the immune system that protect the body from infection and disease. They circulate in the blood and lymph, and are produced in the bone marrow from stem cells. The main types of white blood cells include lymphocytes (T cells and B cells), monocytes, and granulocytes (neutrophils, eosinophils, and basophils), each with a distinct role in detecting and destroying pathogens, producing antibodies, and engulfing foreign materials.

White blood cells (WBCs), or leukocytes, are a crucial part of the immune system, produced in the bone marrow and circulating in the blood and lymph tissue to fight infections, other diseases, and foreign invaders. There are five main types—neutrophils, eosinophils, basophils, lymphocytes, and monocytes—each with specific roles in the body's defense. A white blood cell count (WBC count) is a common blood test that measures the number of WBCs, with an elevated count often indicating an infection or inflammatory condition.

Summary

White blood cells (scientific name leukocytes), also called immune cells or immunocytes, are cells of the immune system that are involved in protecting the body against both infectious disease and foreign entities. White blood cells are generally larger than red blood cells. They include three main subtypes: granulocytes, lymphocytes and monocytes.

All white blood cells are produced and derived from multipotent cells in the bone marrow known as hematopoietic stem cells. Leukocytes are found throughout the body, including the blood and lymphatic system. All white blood cells have nuclei, which distinguishes them from the other blood cells, the anucleated red blood cells (RBCs) and platelets. The different white blood cells are usually classified by cell lineage (myeloid cells or lymphoid cells). White blood cells are part of the body's immune system. They help the body fight infection and other diseases. Types of white blood cells are granulocytes (neutrophils, eosinophils, and basophils), and agranulocytes (monocytes, and lymphocytes (T cells and B cells)). Myeloid cells (myelocytes) include neutrophils, eosinophils, mast cells, basophils, and monocytes.[6] Monocytes are further subdivided into dendritic cells and macrophages. Monocytes, macrophages, and neutrophils are phagocytic. Lymphoid cells (lymphocytes) include T cells (subdivided into helper T cells, memory T cells, cytotoxic T cells), B cells (subdivided into plasma cells and memory B cells), and natural killer cells. Historically, white blood cells were classified by their physical characteristics (granulocytes and agranulocytes), but this classification system is less frequently used now. Produced in the bone marrow, white blood cells defend the body against infections and disease. An excess of white blood cells is usually due to infection or inflammation. Less commonly, a high white blood cell count could indicate certain blood cancers or bone marrow disorders.

The number of leukocytes in the blood is often an indicator of disease, and thus the white blood cell count is an important subset of the complete blood count. The normal white cell count is usually between 4 billion/L and 11 billion/L. In the US, this is usually expressed as 4,000 to 11,000 white blood cells per microliter of blood. White blood cells make up approximately 1% of the total blood volume in a healthy adult, making them substantially less numerous than the red blood cells at 40% to 45%. However, this 1% of the blood makes a huge difference to health because immunity depends on it. An increase in the number of leukocytes over the upper limits is called leukocytosis. It is normal when it is part of healthy immune responses, which happen frequently. It is occasionally abnormal when it is neoplastic or autoimmune in origin. A decrease below the lower limit is called leukopenia, which indicates a weakened immune system.

Details

White blood cells are a part of your immune system that protects your body from infection. These cells circulate through your bloodstream and tissues to respond to injury or illness by attacking any unknown organisms that enter your body.

What are white blood cells?

White blood cells, also known as leukocytes, are responsible for protecting your body from infection. As part of your immune system, white blood cells circulate in your blood and respond to injury or illness.

Function:

What do white blood cells do?

White blood cells protect your body against infection. As your white blood cells travel through your bloodstream and tissues, they locate the site of an infection and act as an army general to notify other white blood cells of their location to help defend your body from an attack of an unknown organism. Once your white blood cell army arrives, they fight the invader by producing antibody proteins to attach to the organism and destroy it.

Anatomy:

Where are white blood cells located?

Your white blood cells are in your bloodstream and travel through blood vessel walls and tissues to locate the site of an infection.

What do white blood cells look like?

Contrary to their name, white blood cells are colorless but can appear as a very light purple to pink color when examined under a microscope and colored with dye. These extremely tiny cells have a round shape with a distinct center membrane (nucleus).

How big are white blood cells?

You can only see white blood cells under a microscope, as they are extremely small.

How many white blood cells are in my body?

White blood cells account for 1% of your blood. There are more red blood cells in your body than white blood cells.

How are white blood cells formed?

White blood cell formation occurs in the soft tissue inside of your bones (bone marrow). Two types of white blood cells (lymphocytes) grow in the thymus gland (T cells) and lymph nodes and spleen (B cells).

What are white blood cells made of?

White blood cells originate from cells that morph into other cells in the body (stem cell) within the soft tissue of your bones (bone marrow).

What are the types of white blood cells?

There are five types of white blood cells:

* Neutrophils: Help protect your body from infections by killing bacteria, fungi and foreign debris.

* Lymphocytes: Consist of T cells, natural killer cells and B cells to protect against viral infections and produce proteins to help you fight infection (antibodies).

* Eosinophils: Identify and destroy parasites, cancer cells and assists basophils with your allergic response.

* Basophils: Produce an allergic response like coughing, sneezing or a runny nose.

* Monocytes: Defend against infection by cleaning up damaged cells.

Conditions and DisordersWhat are the common conditions and disorders that affect white blood cells?

If you have a low white blood cell count, you are likely to get infections (leukopenia). If your white blood cell count is too high (leukocytosis), you may have an infection or an underlying medical condition like leukemia, lymphoma or an immune disorder.

What are common signs or symptoms of white blood cell conditions?

Symptoms of white blood cell conditions, where you may have a count that is too high or too low, include:

* Fever, body aches and chills.

* Wound that is red, swollen, oozes pus or won’t heal.

* Frequent infections.

* Persistent cough or difficulty breathing.

What is a normal white blood cell count?

It is normal for you to produce nearly 100 billion white blood cells each day. After completing a blood draw, a test counts your white blood cells, which equals number of cells per microliter of blood. The normal white blood cell count ranges between 4,000 and 11,000 cells per microliter.

What are common tests to check the number of white blood cells?

A complete blood count (CBC) test identifies information about the cells in your blood. A lab completes this test after a medical professional draws your blood and examines your white and red blood cell count.

White blood cells scan is a test to detect infection or abscesses in your body’s soft tissues. This test involves withdrawing your blood, separating the white blood cells from the sample, tagging them with a radioactive isotope, returning those white blood cells back into your body, then an imaging test will identify areas that show infection or abscess on your body.

What causes a low white blood cell count?

Causes of low white blood cell count include:

* Bone marrow failure (aplastic anemia).

* Bone marrow attacked by cancer cells (leukemia).

* Drug exposure (chemotherapy).

* Vitamin deficiency (B12).

* HIV/AIDS.

A blood test with fewer than 4,000 cells per microliter of blood diagnoses low white blood cells.

What causes a high white blood cell count?

Causes of high white blood cell count include:

* Autoimmune disorders (lupus, rheumatoid arthritis).

* Viral infections (mononucleosis).

* Bacterial infections (sepsis).

* Physical injury or stress.

* Leukemia or Hodgkins disease.

* Allergies.

A blood test with more than 11,000 cells per microliter of blood diagnoses high white blood cells.

What are common treatments for white blood cell disorders?

Treatment for white blood cell disorders vary based on the diagnosis and severity of the condition. Treatment ranges from:

* Taking vitamins.

* Taking antibiotics.

* Surgery to replace or repair bone marrow.

* Blood transfusion.

* Stem cell transplant.

Care:

How do I take care of my white blood cells?

You can take care of your white blood cells by:

* Practicing good hygiene to prevent infection.

* Taking vitamins to boost your immune system.

* Treating medical conditions where white blood cell disorders are a side effect.

White blood cells serve as your first line of defense against injury or illness. Keep your white blood cells healthy by taking vitamins to boost your immune system and practicing good hygiene to prevent infection. If you experience any symptoms like fever and chills, frequent infection, persistent cough or difficulty breathing, contact your healthcare provider to test if your white blood cell count is abnormal.

Additional Information

A white blood cell is a cellular component of the blood that lacks hemoglobin, has a nucleus, is capable of motility, and defends the body against infection and disease by ingesting foreign materials and cellular debris, by destroying infectious agents and cancer cells, or by producing antibodies.

Characteristics of white blood cells

In adults, the bone marrow produces 60 to 70 percent of the white cells (i.e., the granulocytes). The lymphatic tissues, particularly the thymus, the spleen, and the lymph nodes, produce the lymphocytes (comprising 20 to 30 percent of the white cells). The reticuloendothelial tissues of the spleen, liver, lymph nodes, and other organs produce the monocytes (4 to 8 percent of the white cells). A healthy adult human has between 4,500 and 11,000 white blood cells per cubic millimetre of blood. Fluctuations in white cell number occur during the day; lower values are obtained during rest and higher values during exercise.

The survival of white blood cells, as living cells, depends on their continuous production of energy. The chemical pathways utilized are more complex than those of the red cells and are similar to those of other tissue cells. White cells, containing a nucleus and able to produce ribonucleic acid (RNA), can synthesize protein.

Although white cells are found in the circulation, most occur outside the circulation, within tissues, where they fight infections; the few in the bloodstream are in transit from one site to another. As living cells, their survival depends on their continuous production of energy. The chemical pathways utilized are more complex than those of red blood cells and are similar to those of other tissue cells. White cells, containing a nucleus and able to produce ribonucleic acid (RNA), can synthesize protein. White cells are highly differentiated for their specialized functions, and they do not undergo cell division (mitosis) in the bloodstream; however, some retain the capability of mitosis. On the basis of their appearance under a light microscope, white cells are grouped into three major classes—lymphocytes, granulocytes, and monocytes—each of which carries out somewhat different functions.

Major classes of white blood cells

Lymphocytes, which are further divided into B cells and T cells, are responsible for the specific recognition of foreign agents and their subsequent removal from the host. B lymphocytes secrete antibodies, which are proteins that bind to foreign microorganisms in body tissues and mediate their destruction. Typically, T cells recognize virally infected or cancerous cells and destroy them, or they serve as helper cells to assist the production of antibody by B cells. Also included in this group are natural killer (NK) cells, so named for their inherent ability to kill a variety of target cells. In a healthy person, about 25 to 33 percent of white blood cells are lymphocytes.

Granulocytes, the most numerous of the white cells, rid the body of large pathogenic organisms such as protozoans or helminths and are also key mediators of allergy and other forms of inflammation. These cells contain many cytoplasmic granules, or secretory vesicles, that harbour potent chemicals important in immune responses. They also have multilobed nuclei, and because of this they are often called polymorphonuclear cells. On the basis of how their granules take up dye in the laboratory, granulocytes are subdivided into three categories: neutrophils, eosinophils, and basophils. The most numerous of the granulocytes—making up 50 to 80 percent of all white cells—are neutrophils. They are often one of the first cell types to arrive at a site of infection, where they engulf and destroy the infectious microorganisms through a process called phagocytosis. Eosinophils and basophils, as well as the tissue cells called mast cells, typically arrive later. The granules of basophils and of the closely related mast cells contain a number of chemicals, including histamine and leukotrienes, that are important in inducing allergic inflammatory responses. Eosinophils destroy parasites and also help to modulate inflammatory responses.

Monocytes, which constitute between 4 and 8 percent of the total number of white blood cells in the blood, move from the blood to sites of infection, where they differentiate further into macrophages. These cells are scavengers that phagocytose whole or killed microorganisms and are therefore effective at direct destruction of pathogens and cleanup of cellular debris from sites of infection. Neutrophils and macrophages are the main phagocytic cells of the body, but macrophages are much larger and longer-lived than neutrophils. Some macrophages are important as antigen-presenting cells, cells that phagocytose and degrade microbes and present portions of these organisms to T lymphocytes, thereby activating the specific acquired immune response.

Diseases of white blood cells

Specific types of cells are associated with different illnesses and reflect the special function of that cell type in body defense. In general, newborns have a high white blood cell count that gradually falls to the adult level during childhood. An exception is the lymphocyte count, which is low at birth, reaches its highest levels in the first four years of life, and thereafter falls gradually to a stable adult level.

An abnormal increase in white cell number is known as leukocytosis. This condition is usually caused by an increase in the number of granulocytes (especially neutrophils), some of which may be immature (myelocytes). White cell count may increase in response to intense physical exertion, convulsions, acute emotional reactions, pain, pregnancy, labour, and certain disease states, such as infections and intoxications.

A large increase in the numbers of white blood cells in the circulation or bone marrow is a sign of leukemia, a type of cancer of the blood-forming tissues. Some types of leukemia have been related to radiation exposure, as noted in the Japanese population exposed to the first atomic bomb at Hiroshima; other evidence suggests hereditary susceptibility. A number of different leukemias are classified according to the course of the disease and the predominant type of white blood cell involved. For example, myelogenous leukemia affects granulocytes and monocytes, white blood cells that destroy bacteria and some parasites.

An abnormal decrease in white blood cell numbers is known as leukopenia. The count may decrease in response to certain types of infections or drugs or in association with certain conditions, such as chronic anemia, malnutrition, or anaphylaxis.

Certain types of infections are characterized from the beginning by an increase in the number of small lymphocytes unaccompanied by increases in monocytes or granulocytes. Such lymphocytosis is usually of viral origin. Moderate degrees of lymphocytosis are encountered in certain chronic infections, such as tuberculosis and brucellosis. Infectious mononucleosis, caused by the Epstein-Barr virus, is associated with the appearance of unusually large lymphocytes (atypical lymphocytes). These cells represent part of the complex defense mechanism against the virus, and they disappear from the blood when the attack of infectious mononucleosis subsides.

It appears to me that if one wants to make progress in mathematics, one should study the masters and not the pupils. - Niels Henrik Abel.

Nothing is better than reading and gaining more and more knowledge - Stephen William Hawking.

Offline

Pages: 1