Math Is Fun Forum

You are not logged in.

- Topics: Active | Unanswered

#526 2019-11-06 00:09:03

- Jai Ganesh

- Administrator

- Registered: 2005-06-28

- Posts: 52,479

Re: Miscellany

426) Rhinoceros

Rhinoceros, (family Rhinocerotidae), plural rhinoceroses, rhinoceros, or rhinoceri, any of five or six species of giant horn-bearing herbivores that include some of the largest living land mammals. Only African and Asian elephants are taller at the shoulder than the two largest rhinoceros species—the white, or square-lipped (Ceratotherium simum, which some divide into two species [northern white rhinoceros, C. cottoni, and southern white rhinoceros, C. simum]), rhinoceros and the Indian, or greater one-horned (Rhinoceros unicornis), rhinoceros. The white and the black (Diceros bicornis) rhinoceros live in Africa, while the Indian, the Javan (R. sondaicus), and the Sumatran (Dicerorhinus sumatrensis) rhinoceros live in Asia. The precarious state of the surviving species (all but one are endangered) is in direct contrast to the early history of this group as one of the most successful lineages of hoofed mammals. Today the total population of all the rhinoceros species combined is probably less than 30,000. Rhinoceroses today are restricted to eastern and southern Africa and to subtropical and tropical Asia.

Rhinoceroses are characterized by the possession of one or two horns on the upper surface of the snout; these horns are not true horns but are composed of keratin, a fibrous protein found in hair. Modern rhinoceroses are large animals, ranging from 2.5 metres (8 feet) long and 1.5 metres (5 feet) high at the shoulder in the Sumatran rhinoceros to about 4 metres (13 feet) long and nearly 2 metres (7 feet) high in the white rhinoceros. Adults of larger species weigh 3–5 tons. Rhinoceroses are noted for their thick skin, which forms platelike folds, especially at the shoulders and thighs. All rhinos are gray or brown in colour, including the white rhinoceros, which tends to be paler than the others. Aside from the Sumatran rhinoceros, they are nearly or completely hairless, except for the tail tip and ear fringes, but some fossil species were covered with dense fur. The feet of the modern species have three short toes, tipped with broad, blunt nails.

Most rhinoceroses are solitary. Individuals usually avoid each other, but the white rhinoceros lives in groups of up to 10 animals. In solitary species the home territory is crisscrossed with well-worn trails and often marked at the borders with urine and piles of dung.

Rhinoceroses have poor eyesight but acute senses of hearing and smell. Most prefer to avoid humans, but males, and females with calves, may charge with little provocation. The black rhinoceros (Diceros bicornis) is normally ill-tempered and unpredictable and may charge any unfamiliar sound or smell. Despite their bulk, rhinoceroses are remarkably agile; the black rhinoceros can attain a speed of about 45 km (30 miles) per hour, even in thick brush, and can turn around rapidly after missing a charge. Like elephants, rhinoceroses communicate using infrasonic frequencies that are below the threshold of human hearing. The use of infrasonic frequencies is likely an adaptation for rhinoceroses to keep in touch with each other where they inhabit dense vegetation and probably for females to advertise to males when females are receptive to breeding.

Rhinoceroses are by far the largest of the perissodactyls, an order of hoofed mammals that also includes the horses and zebras. One of the features of very large body size in mammals is a low reproductive rate. In rhinoceroses, females do not conceive until about six years of age; gestation is long (16 months in most species), and they give birth to only one calf at a time. The period of birth between calves can range from 2 to 4.5 years. Thus, the loss of a number of breeding-age females to poachers can greatly slow the recovery of rhinoceros populations. However, an Indian rhinoceros female will conceive again quickly if she loses her calf. In this species tigers kill about 10–20 percent of calves. Tigers rarely kill calves older than 1 year, so those Indian rhinoceroses that survive past that point are invulnerable to nonhuman predators.

The three Asian species fight with their razor-sharp lower outer incisor teeth, not with their horns. In Indian rhinoceroses such teeth, or tusks, can reach 13 cm (5 inches) in length among dominant males and inflict lethal wounds on other males competing for access to breeding females. The African species, in contrast, lack these long tusk-like incisors and instead fight with their horns.

The rhinoceros’s horn is also the cause of its demise. Powdered rhinoceros horn has been a highly sought commodity in traditional Chinese medicine—not as an aphrodisiac, as is often widely reported, but as an antifever agent. Substitute agents have been found, particularly pig bone and water buffalo horn, but rhinoceros horn commands tens of thousands of dollars per kilogram in Asian markets. Today poaching remains a serious problem throughout the range of all species of rhinoceros.

The term rhinoceros is sometimes also applied to other, extinct members of the family Rhinocerotidae, a diverse group that includes several dozen fossil genera, among them the woolly rhinoceros (Coelodonta antiquitatis). Early rhinoceroses resembled small horses and lacked horns. (Horns are a relatively recent development in the lineage.) The largest land mammal ever to have lived was not an elephant but Indricotherium, a perissodactyl that was 6 metres (20 feet) long and could browse treetops like a giraffe.

It appears to me that if one wants to make progress in mathematics, one should study the masters and not the pupils. - Niels Henrik Abel.

Nothing is better than reading and gaining more and more knowledge - Stephen William Hawking.

Offline

#527 2019-11-06 14:29:53

- Monox D. I-Fly

- Member

- From: Indonesia

- Registered: 2015-12-02

- Posts: 2,000

Re: Miscellany

The black rhinoceros (Diceros bicornis) is normally ill-tempered and unpredictable and may charge any unfamiliar sound or smell. Despite their bulk, rhinoceroses are remarkably agile; the black rhinoceros can attain a speed of about 45 km (30 miles) per hour, even in thick brush, and can turn around rapidly after missing a charge.

When I was a kid, I was told that a rhinoceros can't turn while charging. It was a lie?

Actually I never watch Star Wars and not interested in it anyway, but I choose a Yoda card as my avatar in honor of our great friend bobbym who has passed away.

May his adventurous soul rest in peace at heaven.

Offline

#528 2019-11-07 00:30:28

- Jai Ganesh

- Administrator

- Registered: 2005-06-28

- Posts: 52,479

Re: Miscellany

Unable to tell.

It appears to me that if one wants to make progress in mathematics, one should study the masters and not the pupils. - Niels Henrik Abel.

Nothing is better than reading and gaining more and more knowledge - Stephen William Hawking.

Offline

#529 2019-11-08 00:07:28

- Jai Ganesh

- Administrator

- Registered: 2005-06-28

- Posts: 52,479

Re: Miscellany

427) Koala

Koala, (Phascolarctos cinereus), also called koala bear, tree-dwelling marsupial of coastal eastern Australia classified in the family Phascolarctidae (suborder Vombatiformes).

The koala is about 60 to 85 cm (24 to 33 inches) long and weighs up to 14 kg (31 pounds) in the southern part of its range (Victoria) but only about half that in subtropical Queensland to the north. Virtually tailless, the body is stout and gray, with a pale yellow or cream-coloured chest and mottling on the rump. The broad face has a wide, rounded, leathery nose, small yellow eyes, and big fluffy ears. The feet are strong and clawed; the two inner digits of the front feet and the innermost digit of the hind feet are opposable for grasping. Owing to the animal’s superficial resemblance to a small bear, the koala is sometimes called, albeit erroneously, the koala bear.

The koala feeds very selectively on the leaves of certain eucalyptus trees. Generally solitary, individuals move within a home range of more than a dozen trees, one of which is favoured over the others. If koalas become too numerous in a restricted area, they defoliate preferred food trees and, unable to subsist on even closely related species, decline rapidly. To aid in digesting as much as 1.3 kg (3 pounds) of leaves daily, the koala has an intestinal pouch (cecum) about 2 metres (7 feet) long, where symbiotic bacteria degrade the tannins and other toxic and complex substances abundant in eucalyptus. This diet is relatively poor in nutrients and provides the koala little spare energy, so the animal spends long hours simply sitting or sleeping in tree forks, exposed to the elements but insulated by thick fur. Although placid most of the time, koalas produce loud, hollow grunts.

The koala is the only member of the family Phascolarctidae. Unlike those of other arboreal marsupials, its pouch opens rearward. Births are single, occurring after a gestation of 34 to 36 days. The youngster (called a joey) first puts its head out of the pouch at about five months of age. For up to six weeks, it is weaned on a soupy predigested eucalyptus called pap that is lapped directly from the mother’s math. Pap is thought to be derived from the cecum. After weaning, the joey emerges completely from the pouch and clings to the mother’s back until it is nearly a year old. A koala can live to about 15 years of age in the wild, somewhat longer in captivity.

Formerly killed in huge numbers for their fur, especially during the 1920s and ’30s, koalas dwindled in number from several million to a few hundred thousand. In the southern part of their range, they became practically extinct except for a single population in Gippsland, Victoria. Some were translocated onto small offshore islands, especially Phillip Island, where they did so well that these koalas were used to restock much of the original range in Victoria and southern New South Wales. Though once again widespread, koala populations are now scattered and separated by urban areas and farmland, which makes them locally vulnerable to extinction. Another problem is the infection of many populations with Chlamydia, which makes the females infertile.

Despite the koala’s having been considered a species of least concern since 1996 by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN), the Australian government added the koala to the country’s threatened species list in 2012.

It appears to me that if one wants to make progress in mathematics, one should study the masters and not the pupils. - Niels Henrik Abel.

Nothing is better than reading and gaining more and more knowledge - Stephen William Hawking.

Offline

#530 2019-11-10 00:12:54

- Jai Ganesh

- Administrator

- Registered: 2005-06-28

- Posts: 52,479

Re: Miscellany

428) Ant

Ant, (family Formicidae), any of approximately 10,000 species of insects (order Hymenoptera) that are social in habit and live together in organized colonies. Ants occur worldwide but are especially common in hot climates. They range in size from about 2 to 25 mm (about 0.08 to 1 inch). Their colour is usually yellow, brown, red, or black. A few genera (e.g., Pheidole of North America) have a metallic lustre.

Typically, an ant has a large head and a slender, oval abdomen joined to the thorax, or midsection, by a small waist. In all ants there are either one or two finlike extensions running across the thin waist region. The antennae are always elbowed. There are two sets of jaws: the outer pair is used for carrying objects such as food and for digging, and the inner pair is used for chewing. Some species have a powerful sting at the tip of the abdomen.

There are generally three castes, or classes, within a colony: queens, males, and workers. Some species live in the nests of other species as parasites. In these species the parasite larvae are given food and nourishment by the host workers. Wheeleriella santschii is a parasite in the nests of Monomorium salomonis, the most common ant of northern Africa.

Most ants live in nests, which may be located in the ground or under a rock or built above ground and made of twigs, sand, or gravel. Carpenter ants (Camponotus) are large black ants common in North America that live in old logs and timbers. Some species live in trees or in the hollow stems of weeds. Tailor, or weaver, ants, found in the tropics of Africa (e.g., Tetramorium), make nests of leaves and similar materials held together with silk secreted by the larvae. Dolichoderus, a genus of ants that are found worldwide, glues together bits of animal feces for its nest. The widely distributed pharaoh ant (Monomarium pharaonis), a small yellowish insect, builds its nest either in houses, when found in cool climates, or outdoors, when it occurs in warm climates.

Army ants, of the subfamily Dorylinae, are nomadic and notorious for the destruction of plant and animal life in their path. The army ants of tropical America (Eciton), for example, travel in columns, eating insects and other invertebrates along the way. Periodically, the colony rests for several days while the queen lays her eggs. As the colony travels, the growing larvae are carried along by the workers. Habits of the African driver ant (Dorylus) are similar.

The red imported fire ant (Solenopsis invicta), introduced into Alabama from South America, had spread throughout the southern United States by the mid-1970s. It inflicts a painful sting and is considered a pest because of the large soil mounds associated with its nests. In some areas the red imported fire ant has been displaced by the invasive tawny crazy ant (also called hairy crazy ant, Nylanderia fulva), a species known in South America that was first detected in the United States (in Texas) in 2002. The hairy crazy ant is extremely difficult to control and is considered to be a major pest and threat to native species and ecosystems.

The life cycle of the ant has four stages, including egg, larva, pupa, and adult, and spans a period of 8 to 10 weeks. The queen spends her life laying eggs. The workers are females and do the work of the colony, with larger individuals functioning as soldiers who defend the colony. At certain times of the year, many species produce winged males and queens that fly into the air, where they mate. The male dies soon afterward, and the fertilized queen establishes a new nest.

The food of ants consists of both plant and animal substances. Certain species, including those of the genus Formica, often eat the eggs and larvae of other ants or those of their own species. Some species eat the liquid secretions of plants. The honey ants (Camponotinae, Dolichoderinae) eat honeydew, a by-product of digestion secreted by certain aphids. The ant usually obtains the liquid by gently stroking the aphid’s abdomen with its antennae. Some genera (Leptothorax) eat the honeydew that has fallen onto the surface of a leaf. The so-called Argentine ant (Iridomyrmex humilis) and the fire ant also eat honeydew. Harvester ants (Messor, Pogonomyrmex) store grass, seeds, or berries in the nest, whereas ants of the genus Trachymyrmex of South America eat only fungi, which they cultivate in their nests. The Texas leafcutter ant (Atta texana) is a pest that often strips the leaves from plants to provide nourishment for its fungus gardens.

The social behaviour of the ants, along with that of the honeybees, is the most complex in the insect world. Slave-making ants, of which there are many species, have a variety of methods for “enslaving” the ants of other species. The queen of Bothriomyrmex decapitans of Africa, for example, allows herself to be dragged by Tapinoma ants into their nest. She then bites off the head of the Tapinoma queen and begins laying her own eggs, which are cared for by the “enslaved” Tapinoma workers. Workers of the slave-making ant Protomognathus americanus raid nests of Temnothorax ants, stealing the latter’s pupae. The pupae are raised by P. americanus to serve as slaves, and, because the Temnothorax pupae become imprinted on the chemical odour of the slave-making ants, the captive ants forage and routinely return to the slave-making ant nest.

It appears to me that if one wants to make progress in mathematics, one should study the masters and not the pupils. - Niels Henrik Abel.

Nothing is better than reading and gaining more and more knowledge - Stephen William Hawking.

Offline

#531 2019-11-10 15:42:03

- Monox D. I-Fly

- Member

- From: Indonesia

- Registered: 2015-12-02

- Posts: 2,000

Re: Miscellany

The red imported fire ant (Solenopsis invicta), introduced into Alabama from South America, had spread throughout the southern United States by the mid-1970s. It inflicts a painful sting and is considered a pest because of the large soil mounds associated with its nests. In some areas the red imported fire ant has been displaced by the invasive tawny crazy ant (also called hairy crazy ant, Nylanderia fulva), a species known in South America that was first detected in the United States (in Texas) in 2002. The hairy crazy ant is extremely difficult to control and is considered to be a major pest and threat to native species and ecosystems.

Wow. Is the bite of a crazy ant very painful to the point that fire ants are nothing compared to them?

Actually I never watch Star Wars and not interested in it anyway, but I choose a Yoda card as my avatar in honor of our great friend bobbym who has passed away.

May his adventurous soul rest in peace at heaven.

Offline

#532 2019-11-12 00:18:11

- Jai Ganesh

- Administrator

- Registered: 2005-06-28

- Posts: 52,479

Re: Miscellany

429) Pancreas

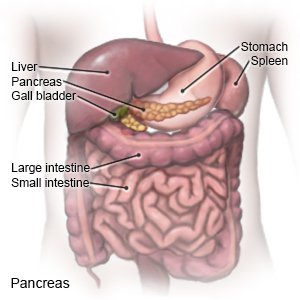

Pancreas, compound gland that discharges digestive enzymes into the gut and secretes the hormones insulin and glucagon, vital in carbohydrate (sugar) metabolism, into the bloodstream.

Anatomy And Exocrine And Endocrine Functions

In humans the pancreas weighs approximately 80 grams (about 3 ounces) and is shaped like a pear. It is located in the upper abdomen, with the head lying immediately adjacent to the duodenum (the upper portion of the small intestine) and the body and tail extending across the midline nearly to the spleen. In adults, most of the pancreatic tissue is devoted to exocrine function, in which digestive enzymes are secreted via the pancreatic ducts into the duodenum. The cells in the pancreas that produce digestive enzymes are called acinar cells (from Latin acinus, meaning “grape”), so named because the cells aggregate to form bundles that resemble a cluster of grapes. Located between the clusters of acinar cells are scattered patches of another type of secretory tissue, collectively known as the islets of Langerhans, named for the 19th-century German pathologist Paul Langerhans. The islets carry out the endocrine functions of the pancreas, though they account for only 1 to 2 percent of pancreatic tissue.

A large main duct, the duct of Wirsung, collects pancreatic juice and empties into the duodenum. In many individuals a smaller duct (the duct of Santorini) also empties into the duodenum. Enzymes active in the digestion of carbohydrates, fat, and protein continuously flow from the pancreas through these ducts. Their flow is controlled by the vagus nerve and by the hormones secretin and cholecystokinin, which are produced in the intestinal mucosa. When food enters the duodenum, secretin and cholecystokinin are released into the bloodstream by secretory cells of the duodenum. When these hormones reach the pancreas, the pancreatic cells are stimulated to produce and release large amounts of water, bicarbonate, and digestive enzymes, which then flow into the intestine.

The endocrine pancreas consists of the islets of Langerhans. There are approximately one million islets that weigh about 1 gram (about 0.04 ounce) in total and are scattered throughout the pancreas. The cells that make up the islets arise from both endodermal and neuroectodermal precursor cells. Approximately 75 percent of the cells in each islet are insulin-producing beta cells, which are clustered centrally in the islet. The remainder of each islet consists of alpha, delta, and F (or PP) cells, which secrete glucagon, somatostatin, and pancreatic polypeptide, respectively, and are located at the periphery of the islet. Each islet is supplied by one or two very small arteries (arterioles) that branch into numerous capillaries. These capillaries emerge and coalesce into small veins outside the islet. The islets also contain many nerve endings (predominantly involuntary, or autonomic, nerves that monitor and control internal organs). The principal function of the endocrine pancreas is the secretion of insulin and other polypeptide hormones necessary for the cellular storage or mobilization of glucose, amino acids, and triglycerides. Islet function may be regulated by signals initiated by autonomic nerves, circulating metabolites (e.g., glucose, amino acids, ketone bodies), circulating hormones, or local (paracrine) hormones.

The pancreas may be the site of acute and chronic infections, tumours, and cysts. Should it be surgically removed, life can be sustained by the administration of insulin and potent pancreatic extracts. Approximately 80 to 90 percent of the pancreas can be surgically removed without producing an insufficiency of either endocrine hormones (insulin and glucagon) or exocrine substances (water, bicarbonate, and enzymes).

Hormonal Control Of Energy Metabolism

The discovery of insulin in 1921 was one of the most important events in modern medicine. It saved the lives of countless patients affected by diabetes mellitus, a disorder of carbohydrate metabolism characterized by the inability of the body to produce or respond to insulin. The discovery of insulin also ushered in the present-day understanding of the function of the endocrine pancreas. The importance of the endocrine pancreas lies in the fact that insulin plays a central role in the regulation of energy metabolism. A relative or absolute deficiency of insulin leads to diabetes mellitus, which is a major cause of disease and death throughout the world.

The pancreatic hormone glucagon, in conjunction with insulin, also plays a key role in maintaining glucose homeostasis and in regulating nutrient storage. An adequate supply of glucose is required for optimal body growth and development and for the function of the central nervous system, for which glucose is the major source of energy. Therefore, elaborate mechanisms have evolved to ensure that blood glucose concentrations are maintained within narrow limits during both feast and famine. Excess nutrients that are consumed can be stored in the body and made available later—for example, when nutrients are in short supply, as during fasting, or when the body is using energy, as during physical activity. Adipose tissue is the principal site of nutrient storage, nearly all in the form of fat. A single gram of fat contains twice as many calories as a single gram of carbohydrate or protein. In addition, the content of water is very low (10 percent) in adipose tissue. Thus, a kilogram of adipose tissue has 10 times the caloric value as the same weight of muscle tissue.

After food is ingested, molecules of carbohydrate are digested and absorbed as glucose. The resulting increase in blood glucose concentrations is followed by a 5- to 10-fold increase in serum insulin concentrations, which stimulates glucose uptake by liver, adipose, and muscle tissues and inhibits glucose release from liver tissue. Fatty acids and amino acids derived from the digestion of fat and protein are also taken up by and stored in the liver and peripheral tissues, especially adipose tissue. Insulin also inhibits lipolysis (the breakdown of fat), preventing the mobilization of fat. Thus, during the “fed,” or anabolic, state, ingested nutrients that are not immediately utilized are stored, a process largely dependent on the food-associated increase in insulin secretion.

A few hours after a meal, when intestinal absorption of nutrients is complete and blood glucose concentrations have decreased toward pre-meal values, insulin secretion decreases, and glucose production by the liver resumes in order to sustain the needs of the brain. Similarly, lipolysis increases, providing fatty acids that can be used as fuel by muscle tissue and glycerol that can be converted into glucose in the liver. As the period of fasting lengthens (e.g., 12 to 14 hours), blood glucose concentrations and insulin secretion continue to decrease, and glucagon secretion increases. The increase in glucagon secretion and concomitant decrease in insulin secretion stimulate the breakdown of glycogen to form glucose (glycogenolysis) and the production of glucose from amino acids and glycerol (gluconeogenesis) in the liver. After liver glycogen is depleted, blood glucose concentrations are maintained by gluconeogenesis. Thus, the fasting, or catabolic, state is characterized by decreased insulin secretion, increased glucagon secretion, and nutrient mobilization from stores in the liver, muscle, and adipose tissue.

With further fasting, the rate of lipolysis continues to increase for several days and then plateaus. A large proportion of the fatty acids released from adipose tissue is converted to keto acids (beta-hydroxybutyric acid and acetoacetic acid, also known as ketone bodies) in the liver, a process that is stimulated by glucagon. These keto acids are small molecules that contain two carbon atoms. The brain, which generally utilizes glucose for energy, begins to use keto acids in addition to glucose. Eventually, more than half of the brain’s daily metabolic energy needs are met by the keto acids, substantially diminishing the need for glucose production by the liver and the need for gluconeogenesis in general. This reduces the need for amino acids produced by muscle breakdown, thus sparing muscle tissue. Starvation is characterized by low serum insulin concentrations, high serum glucagon concentrations, and high serum free fatty acid and keto acid concentrations.

In summary, in the fed state, insulin stimulates the transport of glucose into tissues (to be consumed as fuel or stored as glycogen), the transport of amino acids into tissues (to build or replace protein), and the transport of fatty acids into tissues (to provide a depot of fat for future energy needs). In the fasting state, insulin secretion decreases and glucagon secretion increases. Liver glycogen stores, followed later by protein and fat stores, are mobilized to produce glucose. Ultimately, most nutrient needs are provided by fatty acids mobilized from fat stores.

It appears to me that if one wants to make progress in mathematics, one should study the masters and not the pupils. - Niels Henrik Abel.

Nothing is better than reading and gaining more and more knowledge - Stephen William Hawking.

Offline

#533 2019-11-14 00:37:57

- Jai Ganesh

- Administrator

- Registered: 2005-06-28

- Posts: 52,479

Re: Miscellany

430) Tonsillitis

Overview

Inflamed tonsils

Tonsillitis is inflammation of the tonsils, two oval-shaped pads of tissue at the back of the throat — one tonsil on each side. Signs and symptoms of tonsillitis include swollen tonsils, sore throat, difficulty swallowing and tender lymph nodes on the sides of the neck.

Most cases of tonsillitis are caused by infection with a common virus, but bacterial infections also may cause tonsillitis.

Because appropriate treatment for tonsillitis depends on the cause, it's important to get a prompt and accurate diagnosis. Surgery to remove tonsils, once a common procedure to treat tonsillitis, is usually performed only when bacterial tonsillitis occurs frequently, doesn't respond to other treatments or causes serious complications.

Symptoms

Tonsillitis most commonly affects children between preschool ages and the mid-teenage years. Common signs and symptoms of tonsillitis include:

• Red, swollen tonsils

• White or yellow coating or patches on the tonsils

• Sore throat

• Difficult or painful swallowing

• Fever

• Enlarged, tender glands (lymph nodes) in the neck

• A scratchy, muffled or throaty voice

• Bad breath

• Stomachache, particularly in younger children

• Stiff neck

• Headache

In young children who are unable to describe how they feel, signs of tonsillitis may include:

• Drooling due to difficult or painful swallowing

• Refusal to eat

• Unusual fussiness

When to see a doctor

It's important to get an accurate diagnosis if your child has symptoms that may indicate tonsillitis.

Call your doctor if your child is experiencing:

• A sore throat that doesn't go away within 24 to 48 hours

• Painful or difficult swallowing

• Extreme weakness, fatigue or fussiness

Get immediate care if your child has any of these symptoms:

• Difficulty breathing

• Extreme difficulty swallowing

• Drooling

Causes

Tonsillitis is most often caused by common viruses, but bacterial infections can also be the cause.

The most common bacterium causing tonsillitis is Streptococcus pyogenes (group A streptococcus), the bacterium that causes strep throat. Other strains of strep and other bacteria also may cause tonsillitis.

Why do tonsils get infected?

The tonsils are the immune system's first line of defense against bacteria and viruses that enter your mouth. This function may make the tonsils particularly vulnerable to infection and inflammation. However, the tonsil's immune system function declines after puberty — a factor that may account for the rare cases of tonsillitis in adults.

Risk factors

Risk factors for tonsillitis include:

• Young age. Tonsillitis most often occurs in children, but rarely in those younger than age 2. Tonsillitis caused by bacteria is most common in children ages 5 to 15, while viral tonsillitis is more common in younger children.

• Frequent exposure to germs. School-age children are in close contact with their peers and frequently exposed to viruses or bacteria that can cause tonsillitis.

Complications

Inflammation or swelling of the tonsils from frequent or ongoing (chronic) tonsillitis can cause complications such as:

• Difficulty breathing

• Disrupted breathing during sleep (obstructive sleep apnea)

• Infection that spreads deep into surrounding tissue (tonsillar cellulitis)

• Infection that results in a collection of pus behind a tonsil (peritonsillar abscess)

Strep infection

If tonsillitis caused by group A streptococcus or another strain of streptococcal bacteria isn't treated, or if antibiotic treatment is incomplete, your child has an increased risk of rare disorders such as:

• Rheumatic fever, an inflammatory disorder that affects the heart, joints and other tissues

• Poststreptococcal glomerulonephritis, an inflammatory disorder of the kidneys that results in inadequate removal of waste and excess fluids from blood

Prevention

The germs that cause viral and bacterial tonsillitis are contagious. Therefore, the best prevention is to practice good hygiene. Teach your child to:

• Wash his or her hands thoroughly and frequently, especially after using the toilet and before eating

• Avoid sharing food, drinking glasses, water bottles or utensils

• Replace his or her toothbrush after being diagnosed with tonsillitis

To help your child prevent the spread of a bacterial or viral infection to others:

• Keep your child at home when he or she is ill

• Ask your doctor when it's all right for your child to return to school

• Teach your child to cough or sneeze into a tissue or, when necessary, into his or her elbow

• Teach your child to wash his or her hands after sneezing or coughing

It appears to me that if one wants to make progress in mathematics, one should study the masters and not the pupils. - Niels Henrik Abel.

Nothing is better than reading and gaining more and more knowledge - Stephen William Hawking.

Offline

#534 2019-11-16 00:12:09

- Jai Ganesh

- Administrator

- Registered: 2005-06-28

- Posts: 52,479

Re: Miscellany

431) Hyena

Hyena, (family Hyaenidae), also spelled hyaena, any of three species of coarse-furred, doglike carnivores found in Asia and Africa and noted for their scavenging habits. Hyenas have long forelegs and a powerful neck and shoulders for dismembering and carrying prey. Hyenas are tireless trotters with excellent sight, hearing, and smell for locating carrion, and they are proficient hunters as well. All hyenas are more or less nocturnal.

Intelligent, curious, and opportunistic in matters of diet, hyenas frequently come into contact with humans. The spotted, or laughing, hyena (Crocuta crocuta) is the largest species and will burglarize food stores, steal livestock, occasionally kill people, and consume wastes—habits for which they are usually despised, even by the Masai, who leave out their dead for hyenas. Even so, hyena body parts are sought for traditional tokens and potions made to cure barrenness, grant wisdom, and enable the blind to find their way around. Brown hyenas (Parahyaena brunnea or sometimes Hyaena brunnea) are blamed for many livestock deaths that they probably do not cause. Similarly, from North Africa eastward to India, striped hyenas (H. hyaena) are blamed when small children disappear and for supposedly attacking small livestock and digging up graves. In consequence, some populations have been persecuted nearly to extinction. All three species are in decline outside protected areas.

Spotted hyenas range south of the Sahara except in rainforests. They are ginger-coloured with patterns of dark spots unique to each individual, and females are larger than males. Weighing up to 82 kg (180 pounds), they can measure almost 2 metres (6.6 feet) long and about 1 metre tall at the shoulder. Spotted hyenas communicate using moans, yells, giggles, and whoops, and these sounds may carry several kilometres. Gestation is about 110 days, and annual litter size is usually two cubs, born in any month.

The spotted hyena hunts everything from young hippos to fish, though antelopes are more common. In East and Southern Africa, they kill most of their own food, chasing wildebeest, gazelles, and zebras at up to 65 km (40 miles) per hour for 3 km. Contrary to popular belief, healthy as well as weakened individuals are taken. One or two animals may start the chase, but dozens might be in on the kill; an adult zebra mare and her two-year-old foal (370 kg total weight) were observed being torn apart and consumed by 35 hyenas in half an hour. Strong jaws and broad molars allow the animal to get at every part of a carcass and crush bones, which are digested in the stomach by highly concentrated hydrochloric acid. Spotted hyenas sometimes go several days between meals, as the stomach can hold 14.5 kg of meat.

Living in clans of 5 to 80 individuals, spotted hyenas mark the boundaries of their territory with dung piles (“latrines”) and scent from anal glands. Females’ genitals externally resemble males’ and have social importance in the genital greeting, in which animals lift the hind leg to allow mutual inspection. The males/females have a linear dominance hierarchy, the lowest female outranking the highest male. The dominant female monopolizes carcasses when she can, which results in better nutrition for her cubs. The dominant male obtains most matings. For 6 months the cubs’ only food is mother’s milk; nursing bouts may last four hours. Where prey is migratory, the mother “commutes” 30 km or more from the den, and she may not see her cubs for three days. After 6 months the cubs begin eating meat from kills, but they continue to drink milk until 14 months old. Female cubs inherit the status of their mothers; young males sometimes move to other clans, where they are more likely to breed.

The smaller brown hyena weighs about 40 kg; the coat is shaggy and dark with an erectile white mane over the neck and shoulders and horizontal white bands on the legs. The brown hyena lives in Southern Africa and western coastal deserts, where it is called the beach, or strand, wolf. Birds and their eggs, insects, and fruit are staples, but leftovers from kills made by lions, cheetahs, and spotted hyenas are very important seasonally. Small mammals and reptiles are occasionally killed. After 3 months’ gestation, cubs (usually three) are born anytime during the year and are weaned by 15 months of age. Like spotted hyenas, brown hyenas live in clans that mark and defend territory, but behaviour differs in several critical ways: adult females nurse each other’s cubs; other clan members take food to the cubs; and females do not outrank males.

Five races of striped hyenas live in scrub woodland as well as in arid and semiarid open country from Morocco to Egypt and Tanzania, Asia Minor, the Arabian Peninsula, the Caucasus, and India. These small hyenas average 30–40 kg. Colour is pale gray with black throat fur and stripes on the body and legs. The hair is long, with a crest running from behind the ears to the tail; the crest is erected to make the animal look larger. Striped hyenas apparently do not scent-mark or defend territory. Litters of one to four cubs are born any time during the year after a 3-month gestation; they are weaned at 10–12 months. A female’s offspring may stay and help raise her new cubs. Striped hyenas have a diet much like that of brown hyenas: insects, fruit, and small vertebrates. In Israel striped hyenas are pests of melon and date crops.

Order Carnivora branched into dog and cat lineages 50 million years ago; hyenas arose from the cat group. Thus, although hyenas look like dogs, they are actually more closely related to cats. Family Hyaenidae diverged about 30 million years ago. Early hyaenids did not all have bone-crushing molars; those were probably a recent development as some hyenas exploited large carcasses left by sabre-toothed cats. Hyaenidae also includes the aardwolf, which looks like a small striped hyena. It has a specialized diet of insects and belongs to a subfamily separate from hyenas.

It appears to me that if one wants to make progress in mathematics, one should study the masters and not the pupils. - Niels Henrik Abel.

Nothing is better than reading and gaining more and more knowledge - Stephen William Hawking.

Offline

#535 2019-11-18 00:29:52

- Jai Ganesh

- Administrator

- Registered: 2005-06-28

- Posts: 52,479

Re: Miscellany

432) Mosquito

Mosquito, (family Culicidae), any of approximately 3,500 species of familiar insects in the fly order, Diptera, that are important in public health because of the bloodsucking habits of the females. Mosquitoes are known to transmit serious diseases, including yellow fever, Zika fever, malaria, filariasis, and dengue.

Physical Features And Behaviour

The slender, elongated body of the adult is covered with scales as are the veins of the wings. Mosquitoes are also characterized by long, fragile-looking legs and elongated, piercing mouthparts. The feathery antennae of the male are generally bushier than those of the female. The males, and sometimes the females, feed on nectar and other plant juices. In most species, however, the females require the proteins obtained from a blood meal in order to mature their eggs. Different species of mosquitoes show preferences and, in many cases, narrow restrictions as to host animals.

The eggs are laid on a surface of water and hatch into aquatic larvae, or wrigglers, which swim with a jerking, wriggling movement. In most species, larvae feed on algae and organic debris, although a few are predatory and may even feed on other mosquitoes. Unlike most insects, mosquitoes in the pupal stage, called tumblers, are active and free-swimming. The pupae breathe by means of tubes on the thorax. The adults mate soon after emerging from their pupal cases. The duration of the life cycle varies greatly depending on the species.

Mosquitoes are apparently attracted to host animals by moisture, lactic acid, carbon dioxide, body heat, and movement. The mosquito’s hum results from the high frequency of its wingbeats, and the female’s wingbeat frequency may serve as a means of gender recognition.

Anopheles Mosquitoes

There are three important mosquito genera. Anopheles, the only known carrier of malaria, also transmits filariasis and encephalitis. Anopheles mosquitoes are easily recognized in their resting position, in which the proboscis, head, and body are held on a straight line to each other but at an angle to the surface. The spotted colouring on the wings results from coloured scales. Egg laying usually occurs in water containing heavy vegetation. The female deposits her eggs singly on the water surface. Anopheles larvae lie parallel to the water surface and breathe through posterior spiracular plates on the abdomen instead of through a tube, as do most other mosquito larvae. The life cycle is from 18 days to several weeks.

Culex Mosquitoes

The genus Culex is a carrier of viral encephalitis and, in tropical and subtropical climates, of filariasis. It holds its body parallel to the resting surface and its proboscis is bent downward relative to the surface. The wings, with scales on the veins and the margin, are uniform in colour. The tip of the female’s abdomen is blunt and has retracted cerci (sensory appendages). Egg laying may occur on almost any body of fresh water, including standing polluted water. The eggs, which float on the water, are joined in masses of 100 or more. The long and slender Culex larvae have breathing tubes that contain hair tufts. They hang head downward at an angle of 45° from the water surface. The life cycle, usually 10 to 14 days, may be longer in cold weather. The northern house mosquito (C. pipiens) is the most abundant species in northern regions, while the southern house mosquito (C. quinquefasciatus) is abundant in southern regions, namely the tropics and subtropics.

Aedes Mosquitoes

The genus Aedes carries the pathogens that cause yellow fever, dengue, Zika fever, and encephalitis. Like Culex, it holds its body parallel to the surface with the proboscis bent down. The wings are uniformly coloured. Aedes may be distinguished from Culex by its silver thorax with white markings and posterior spiracular bristles. The tip of the female’s abdomen is pointed and has protruding cerci. Aedes usually lays eggs in floodwater, rain pools, or salt marshes. The eggs are capable of withstanding long periods of dryness. The short, stout larvae have a breathing tube containing a pair of tufts, and the larvae hang head down at a 45° angle from the water surface. The life cycle may be as short as 10 days or, in cool weather, as long as several months. A. aegypti, the important carrier of the virus responsible for yellow fever, has white bands on its legs and spots on its abdomen and thorax. This domestic species breeds in almost any kind of container, from flower pots to discarded car-tire casings. The eastern salt marsh mosquito (A. sollicitans), the black salt marsh mosquito (A. taeniorhynchus), and the summer salt marsh mosquito (A. dorsalis) are important mosquitoes in coastal marsh areas that experience daily or occasional flooding with brackish or salt water. They are prolific breeders, strong fliers, and irritants to animals, including humans.

Mosquito Control

Because mosquitoes are such prolific carriers of infectious diseases, preventing them from feeding on humans is considered a key global health strategy. The likelihood of disease transmission can be reduced through the use of mosquito repellent, long clothing that covers the arms and legs, screens in open doors and windows, and insecticide-treated mosquito bed nets. Mosquito populations can be controlled in part through the elimination of sources of standing water, which provide ideal breeding sites for mosquitoes. A surface film of oil can be applied to standing water to clog the breathing tubes of wrigglers, which may also be killed by larvicides. Insecticides at times are used to destroy adult mosquitoes indoors.

Researchers have investigated the possibility of manipulating mosquito populations to prevent the production of viable mosquito offspring, thereby reducing the number of mosquitoes. Researchers have also identified ways in which male mosquitoes may be genetically engineered to transmit a gene to their offspring that causes the offspring to die before becoming mature in mating. Scientists have found that female mosquitoes are less attracted to humans when exposed to small compounds related to the neurotransmitter molecule neuropeptide Y. These compounds potentially can be emitted via dispensers in areas where mosquitoes are abundant, helping to deter them from biting humans.

It appears to me that if one wants to make progress in mathematics, one should study the masters and not the pupils. - Niels Henrik Abel.

Nothing is better than reading and gaining more and more knowledge - Stephen William Hawking.

Offline

#536 2019-11-18 15:33:11

- Monox D. I-Fly

- Member

- From: Indonesia

- Registered: 2015-12-02

- Posts: 2,000

Re: Miscellany

Unlike most insects, mosquitoes in the pupal stage, called tumblers, are active and free-swimming.

Now, what chrysalis would be scarier than a free-moving chrysalis of a vampire bug...

Actually I never watch Star Wars and not interested in it anyway, but I choose a Yoda card as my avatar in honor of our great friend bobbym who has passed away.

May his adventurous soul rest in peace at heaven.

Offline

#537 2019-11-20 00:31:47

- Jai Ganesh

- Administrator

- Registered: 2005-06-28

- Posts: 52,479

Re: Miscellany

433) Shrew

Shrew, (family Soricidae), any of more than 350 species of insectivores having a mobile snout that is covered with long sensitive whiskers and overhangs the lower lip. Their large incisor teeth are used like forceps to grab prey; the upper pair is hooked, and the lower pair extends forward. Shrews have a foul odour caused by scent glands on the flanks as well as other parts of the body.

Shrews are small mammals with cylindrical bodies, short and slender limbs, and clawed digits. Their eyes are small but are usually visible in the fur, and the ears are rounded and moderately large, except in short-tailed shrews and water shrews. Tail length varies among species, some being much shorter than the body and others appreciably longer. The genders are not immediately distinguishable, as the testes are retained in the male’s abdominal cavity and do not descend. The brain’s cerebral hemispheres are small, but the olfactory lobes are prominent, which reflects less intelligence and manipulative ability but an enhanced sense of smell. The 26 to 32 white or red-tipped teeth are not replaced during the animal’s life (milk teeth are shed before birth).

Natural History

Most shrews are active all year and by day and night, with regular periods of rest. They eat primarily insects and other invertebrates but also take small vertebrates, seeds, and fungi. North American short-tailed shrews (genus Blarina) and Old World water shrews (genus Neomys) produce toxic saliva for immobilizing prey. Shrews have high metabolic rates and may consume more than their own weight in food daily; they cannot survive for more than a few hours without eating. As a result, shrew life consists largely of a frenetic search for food. Terrestrial shrews have acute senses of hearing, smell, and touch. They probe in litter and soil with their muzzle and dig out any invertebrates detected by smell and by their sensitive whiskers. Large prey is pinned with the front feet but grabbed by the mouth and manipulated with the flexible muzzle, with food being pushed sideways as it is chewed. Amphibious species depend almost entirely on touch to detect prey underwater. Shrews emit clicks, twitters, chirps, squeaks, churls, whistles, barks, and ultrasonic sounds in contexts of alarm, defense, aggression, courtship, interactions between mother and young, and exploration and foraging. Shrews have 2 to 10 blind, hairless young in one or more annual litters; gestation lasts up to 28 days. The mother is attentive and occasionally relocates, carrying the young by the neck or pushing them along to the new nest. When the young are old enough, they may form a chain, each grasping the base of the tail of the one ahead, trailing behind the mother as she escapes from disturbances or relocates. This behaviour is called caravanning.

Shrews are found throughout North America to northwestern South America, Africa, Eurasia, and island groups east of mainland Asia to the Aru Islands on the Australian continental shelf. They have adapted to a wide variety of environments, inhabiting tundra, coniferous, deciduous, and tropical forests, savannas, humid and arid grasslands, and deserts. More than 40 percent of the living species (145 of 325) are indigenous to Africa, with 16 species being recorded from one location in southeastern Central African Republic. The Asian house shrew (Suncus murinus) has been introduced into parts of Arabia, Africa, Madagascar, and some Pacific and Indian Ocean islands.

Form And Function

The common Eurasian shrew (Sorex araneus) represents the average size of most species, weighing up to 14 grams (0.5 ounce) and having a body 6 to 8 cm (2 to 3 inches) long and a shorter tail (5 to 6 cm). One of the smallest mammals known is the pygmy white-toothed shrew (Suncus etruscus) of Eurasia and North Africa, weighing between 1.2 and 2.7 grams (0.04 to 1 ounce) and having a body 4 to 5 cm (1.6 to 2 inches) long and a shorter tail (2 to 3 cm [0.8 to 1.2 inches]). Among the largest is the armoured shrew (Scutisorex somereni) of equatorial Africa, which weighs up to 113 grams (about 4 ounces) and has a body 12 to 15 cm (4.7 to 5.9 inches) long and a tail 8 to 10 cm (3.1 to 3.9 inches) long. The short, dense, soft fur of shrews ranges from gray to black, with either slightly paler tones or white on the underparts. Some species of Sorex are tricoloured, having a dark brown back, grayish brown sides, and grayish undersides. The piebald shrew (genus Diplomesodon) is white with gray along the head and back.

Body form is similar in all shrews, but modifications in anatomical details reflect different lifestyles. For example, most shrews live on the ground, but some tropical species, such as the forest musk shrews (genus Sylvisorex) of Africa and white-toothed shrews (genus Crocidura) of Asia also forage and travel in bushes, vines, and small trees beneath the forest canopy. These species have long feet and toes and a tail much longer than the body.

Other shrews are adapted for burrowing. These are the North American short-tailed shrews (genus Blarina), Kenyan shrews (genus Surdisorex), the Asian mole shrew (Anourosorex squamipes), and Kelaart’s long-clawed shrew (Feroculus feroculus) of Sri Lanka. All have minute eyes obscured by the fur, very small ears also hidden in the fur, long digging claws on the forefeet, and short tails. They construct and forage within subsurface burrows, spending only limited time on the surface.

Water shrews have especially small eyes (covered with skin in genus Nectogale). These are amphibious species that den on land and forage in water. A bizarre and unexplained specialization is shown by the African Scutisorex somereni. It has additional and enlarged lumbar vertebrae interlocked by numerous bony spines, forming a flexible and very strong backbone. This shrew can support the weight of a person.

Classification And Paleontology

The 24 genera of “true” shrews are classified in three subfamilies (Crocidurinae, Soricinae, and Myosoricinae) within the family Soricidae. Soricids are members of the order Soricimorpha, which belongs to a larger group of mammals called insectivores. Elephant shrews and tree shrews are not classified with soricids as part of this group. The evolutionary history of shrews is long, extending to the Middle Eocene Epoch (48 to 41.3 million years ago) of North America; more recent fossils have been found in Africa, Asia, Europe, and South America.

It appears to me that if one wants to make progress in mathematics, one should study the masters and not the pupils. - Niels Henrik Abel.

Nothing is better than reading and gaining more and more knowledge - Stephen William Hawking.

Offline

#538 2019-11-22 00:19:31

- Jai Ganesh

- Administrator

- Registered: 2005-06-28

- Posts: 52,479

Re: Miscellany

434) Flamingo

Flamingo, (order Phoenicopteriformes), any of six species of tall, pink wading birds with thick downturned bills. Flamingos have slender legs, long, graceful necks, large wings, and short tails. They range from about 90 to 150 cm (3 to 5 feet) tall.

Flamingos are highly gregarious birds. Flocks numbering in the hundreds may be seen in long, curving flight formations and in wading groups along the shore. On some of East Africa’s large lakes, more than a million lesser flamingos (Phoeniconaias minor) gather during the breeding season. In flight, flamingos present a striking and beautiful sight, with legs and neck stretched out straight, looking like white and rosy crosses with black arms. No less interesting is the flock at rest, with their long necks twisted or coiled upon the body in any conceivable position. Flamingos are often seen standing on one leg. Various reasons for this habit have been suggested, such as regulation of body temperature, conservation of energy, or merely to dry out the legs.

The nest is a truncated cone of muddy clay piled up a few inches in a shallow lagoon; both parents share the monthlong incubation of the one or two chalky-white eggs that are laid in the hollow of the cone. Downy white young leave the nest in two or three days and are fed by regurgitation of partly digested food by the adults.

Subadults are whitish, acquiring the pink plumage with age. To feed, flamingos tramp the shallows, head down and bill underwater, stirring up organic matter with their webbed feet. They eat various types of food, including diatoms, algae, blue-green algae, and invertebrates such as minute mollusks and crustaceans. While the head swings from side to side, food is strained from the muddy water with small comblike structures inside the bill. The bird’s pink colour comes from its food, which contains carotenoid pigments. The diet of flamingos kept in zoos is sometimes supplemented with food colouring to keep their plumage from fading.

The greater flamingo (Phoenicopterus ruber) breeds in large colonies on the coasts of the Atlantic Ocean and Gulf of Mexico in tropical and subtropical America. There are two subspecies of the greater flamingo: the Caribbean flamingo (P. ruber ruber) and the Old World flamingo (P. ruber roseus) of Africa and southern Europe and Asia. The Chilean flamingo (Phoenicopterus chilensis) is primarily an inland species. Two smaller species that live high in the Andes Mountains of South America are the Andean flamingo (Phoenicoparrus andinus) and the puna, or James’s, flamingo (Phoenicoparrus jamesi). The former has a pink band on each of its yellow legs, and the latter was thought extinct until a remote population was discovered in 1956.

The lesser flamingo (Phoeniconaias minor), which inhabits the lake district of East Africa and parts of South Africa, Madagascar, and India, is the most abundant. It is also the smallest and the deepest in colour. In ancient Rome, flamingo tongues were eaten as a rare delicacy.

Flamingos constitute the family Phoenicopteridae, which is the only family in the order Phoenicopteriformes. They are sometimes classified in the order Ciconiiformes (herons and storks) but also show similarities to anseriforms (ducks and geese), charadriiforms (shorebirds), and pelecaniforms (pelicans and cormorants).

It appears to me that if one wants to make progress in mathematics, one should study the masters and not the pupils. - Niels Henrik Abel.

Nothing is better than reading and gaining more and more knowledge - Stephen William Hawking.

Offline

#539 2019-11-22 15:32:46

- Monox D. I-Fly

- Member

- From: Indonesia

- Registered: 2015-12-02

- Posts: 2,000

Re: Miscellany

The bird’s pink colour comes from its food, which contains carotenoid pigments.

Isn't carotene orange instead of pink, though?

Actually I never watch Star Wars and not interested in it anyway, but I choose a Yoda card as my avatar in honor of our great friend bobbym who has passed away.

May his adventurous soul rest in peace at heaven.

Offline

#540 2019-11-22 16:21:50

- Jai Ganesh

- Administrator

- Registered: 2005-06-28

- Posts: 52,479

Re: Miscellany

ganesh wrote:The bird’s pink colour comes from its food, which contains carotenoid pigments.

Isn't carotene orange instead of pink, though?

Carotenoids, also called tetraterpenoids, are yellow, orange, and red organic pigments that are produced by plants and algae, as well as several bacteria and fungi. Carotenoids give the characteristic color to pumpkins, carrots, corn, tomatoes, canaries, flamingos, and daffodils.

“Carotenoids” is a generic term used to designate the majority of pigments naturally found in animal and plant kingdoms. This group of fat-soluble pigments comprises more than 700 compounds responsible for the red, orange, and yellow colors. Most carotenoids are hydrocarbons containing 40 carbon atoms and two terminal rings.

Carotenes contain no oxygen atoms. They absorb ultraviolet, violet, and blue light and scatter orange or red light, and (in low concentrations) yellow light.

The bright pink color of flamingos comes from beta carotene, a red-orange pigment that’s found in high numbers within the algae, larvae, and brine shrimp that flamingos eat in their wetland environment.

It appears to me that if one wants to make progress in mathematics, one should study the masters and not the pupils. - Niels Henrik Abel.

Nothing is better than reading and gaining more and more knowledge - Stephen William Hawking.

Offline

#541 2019-11-24 00:33:58

- Jai Ganesh

- Administrator

- Registered: 2005-06-28

- Posts: 52,479

Re: Miscellany

435) Pen

Pen, tool for writing or drawing with a coloured fluid such as ink.

The earliest ancestor of the pen probably was the brush the Chinese used for writing by the 1st millennium BCE. The early Egyptians employed thick reeds for pen like implements about 300 BCE. A specific allusion to the quill pen occurs in the 7th-century writings of St. Isidore of Sevilla, but such pens made of bird feathers were probably in use at an even earlier date. They provided a degree of writing ease and control never realized before and were used in Europe until the mid-19th century, when metallic pens and pen nibs (writing points) largely supplanted them. Such devices were known in Classical times but were little used (a bronze pen was found in the ruins of Pompeii). John Mitchell of Birmingham, England, is credited with having introduced the machine-made steel pen point in 1828. Two years later the English inventor James Perry sought to produce more-flexible steel points by cutting a centre hole at the top of a central slit and then making additional slits on either side.

The inconvenience of having to continually dip a pen to replenish its ink supply stimulated the development of the fountain pen, a type of pen in which ink is held in a reservoir and passes to the writing point through capillary channels. The first practical version of the fountain pen was produced in 1884 by the American inventor L.E. Waterman.

Ballpoint pens date from the late 19th century. Commercial models appeared in 1895, but the first satisfactory model was patented by Lázló Bíró, a Hungarian living in Argentina. His ballpoint pen, commonly called the “biro,” became popular in Great Britain during the late 1930s, and by the mid-1940s pens of this type were widely used throughout much of the world. The writing tip of a ballpoint pen consists of a metal ball, housed in a socket, that rotates freely and rolls quick-drying ink onto the writing surface. The ball is constantly bathed in ink from a reservoir, one end of which is open and attached to the writing tip.

Soft-tip pens that use points made of porous materials became commercially available during the 1960s. In such pens a synthetic polymer of controlled porosity transfers ink from the reservoir to the writing surface. These fibre-tipped pens can be used for lettering and drawing as well as for writing and may be employed on surfaces such as plastic and glass.

It appears to me that if one wants to make progress in mathematics, one should study the masters and not the pupils. - Niels Henrik Abel.

Nothing is better than reading and gaining more and more knowledge - Stephen William Hawking.

Offline

#542 2019-11-26 00:20:41

- Jai Ganesh

- Administrator

- Registered: 2005-06-28

- Posts: 52,479

Re: Miscellany

436) Yak

Yak, (Bos grunniens), long-haired, short-legged oxlike mammal that was probably domesticated in Tibet but has been introduced wherever there are people at elevations of 4,000–6,000 metres (14,000–20,000 feet), mainly in China but also in Central Asia, Mongolia, and Nepal.

Wild yaks are sometimes referred to as a separate species (Bos mutus) to differentiate them from domestic yaks, although they are freely interbred with various kinds of cattle. Wild yaks are larger, the bulls standing up to 2 metres tall at the shoulder and weighing over 800 kg (1,800 pounds); cows weigh less than half as much. In China, where they are known as “hairy cattle,” yaks are heavily fringed with long black hair over a shorter blackish or brown undercoat that can keep them warm to –40 °C (−40 °F). Colour in domesticated yaks is more variable, and white splotches are common. Like bison (genus Bison), the head droops before high massive shoulders; horns are 80 cm (30 inches) long in the males, 50 cm in females.

It is not known with certainty when yaks were domesticated, although it is likely that they were first bred as beasts of burden for the caravans of Himalayan trade routes. Yaks’ lung capacity is about three times that of cattle, and they have more and smaller red blood cells, improving the blood’s ability to transport oxygen. Domesticated yaks number at least 12 million and were bred for tractability and high milk production. Yaks are also used for plowing and threshing, as well as for meat, hides, and fur. The dried dung of the yak is the only obtainable fuel on the treeless Tibetan plateau.

Ruminant grazers, wild yaks migrate seasonally to the lower plains to eat grasses and herbs. When it gets too warm, they retreat to higher plateaus to eat mosses and lichens, which they rasp off rocks with their rough tongues. Their dense fur and few sweat glands make life below 3,000 metres difficult, even in winter. Yaks obtain water by eating snow when necessary. In the wild, they live in mixed herds of about 25, though some males live in bachelor groups or alone. Yaks seasonally aggregate into larger groups. Breeding occurs in September–October. Calves are born about nine months later and nursed for a full year. The mother breeds again in the fall after the calf has been weaned.

Wild yaks once extended from the Himalayas to Lake Baikal in Siberia, and in the 1800s they were still numerous in Tibet. After 1900 they were hunted almost to extinction by Tibetan and Mongolian herders and military personnel. Small numbers survive in northern Tibet and the Ladakh steppe of India, but they are not effectively protected. They are also endangered because of interbreeding with domestic cattle.

In the family Bovidae, the yak belongs to the same genus as cattle as well as the banteng, gaur, and kouprey of Southeast Asia. More distantly related are the American and European bison. Bos and Bison diverged from water buffalo (genus Bubalus) and other wild bovines about three million years ago. Despite its ability to breed with cattle, it has been argued that the yak should be returned to its former genus, Poephagus.

It appears to me that if one wants to make progress in mathematics, one should study the masters and not the pupils. - Niels Henrik Abel.

Nothing is better than reading and gaining more and more knowledge - Stephen William Hawking.

Offline

#543 2019-11-26 14:05:49

- Monox D. I-Fly

- Member

- From: Indonesia

- Registered: 2015-12-02

- Posts: 2,000

Re: Miscellany

In the family Bovidae, the yak belongs to the same genus as cattle as well as the banteng, gaur, and kouprey of Southeast Asia.

Huh? We Indonesian think that "bull" is just the English word for "banteng". They are different?

Actually I never watch Star Wars and not interested in it anyway, but I choose a Yoda card as my avatar in honor of our great friend bobbym who has passed away.

May his adventurous soul rest in peace at heaven.

Offline

#544 2019-11-26 14:21:50

- Jai Ganesh

- Administrator

- Registered: 2005-06-28

- Posts: 52,479

Re: Miscellany

ganesh wrote:In the family Bovidae, the yak belongs to the same genus as cattle as well as the banteng, gaur, and kouprey of Southeast Asia.

Huh? We Indonesian think that "bull" is just the English word for "banteng". They are different?

I think they are all the same!

It appears to me that if one wants to make progress in mathematics, one should study the masters and not the pupils. - Niels Henrik Abel.

Nothing is better than reading and gaining more and more knowledge - Stephen William Hawking.

Offline

#545 2019-11-28 00:48:17

- Jai Ganesh

- Administrator

- Registered: 2005-06-28

- Posts: 52,479

Re: Miscellany

437) Strawberry

Strawberry, (genus Fragaria), genus of more than 20 species of flowering plants in the rose family (Rosaceae) and their edible fruit. Strawberries are native to the temperate regions of the Northern Hemisphere, and cultivated varieties are widely grown throughout the world. The fruits are rich in vitamin C and are commonly eaten fresh as a dessert fruit, are used as a pastry or pie filling, and may be preserved in many ways. The strawberry shortcake—made of fresh strawberries, sponge cake, and whipped cream—is a traditional American dessert.

Strawberries are low-growing herbaceous plants with a fibrous root system and a crown from which arise basal leaves. The leaves are compound, typically with three leaflets, sawtooth-edged, and usually hairy. The flowers, generally white, rarely reddish, are borne in small clusters on slender stalks arising, like the surface-creeping stems, from the axils of the leaves. As a plantages, the root system becomes woody, and the “mother” crown sends out runners (e.g., stolons) that touch ground and root, thus enlarging the plant vegetatively. Botanically, the strawberry fruit is considered an “accessory fruit” and is not a true berry. The flesh consists of the greatly enlarged flower receptacle and is embedded with the many true fruits, or achenes, which are popularly called seeds.

The cultivated large-fruited strawberry (Fragaria ×ananassa) originated in Europe in the 18th century. Most countries developed their own varieties during the 19th century, and those are often specially suitable for the climate, day length, altitude, or type of production required in a particular region. Strawberries are produced commercially both for immediate consumption and for processing as frozen, canned, or preserved berries or as juice. Given the perishable nature of the berries and the unlikelihood of mechanical picking, the fruit is generally grown near centres of consumption or processing and where sufficient labour is available. The berries are hand picked directly into small baskets and crated for marketing or put into trays for processing. Early crops can be produced under glass or plastic covering. Strawberries are very perishable and require cool dry storage.

The strawberry succeeds in a surprisingly wide range of soils and situations and, compared with other horticultural crops, has a low fertilizer requirement. It is, however, susceptible to drought and requires moisture-retaining soil or irrigation by furrow or sprinkler. Additionally, the plants are susceptible to nematodes and pathogenic soil fungi, and many growers sterilize the soil with chemicals such as methyl bromide prior to planting. Runner plants are planted in early autumn if a crop is required the next year. If planted in winter or spring, the plants are deblossomed to avoid a weakening crop the first year. Plants are usually retained for one to four years. Runners may be removed from the spaced plants, or a certain number may be allowed to form a matted row alongside the original parent plants. In areas with severe winters, plants are put out in the spring and protected during the following winters by covering the rows with straw or other mulches.

Wild strawberries grow in a variety of habitats, ranging from open woodlands and meadows to sand dunes and beaches. The woodland, or alpine, strawberry (F. vesca) can be found throughout much of the Northern Hemisphere and bears small intensely flavourful fruits. Common North American species include the Virginia wild strawberry (F. virginiana) and the beach, or coastal, strawberry (F. chiloensis). The musk, or hautbois, strawberry (F. moschata) is native to Europe and is cultivated commercially in some areas for its unique musky aroma and flavour.

It appears to me that if one wants to make progress in mathematics, one should study the masters and not the pupils. - Niels Henrik Abel.

Nothing is better than reading and gaining more and more knowledge - Stephen William Hawking.

Offline

#546 2019-11-30 01:13:54

- Jai Ganesh

- Administrator

- Registered: 2005-06-28

- Posts: 52,479

Re: Miscellany

438) Dactyloscopy

Dactyloscopy, the science of fingerprint identification.

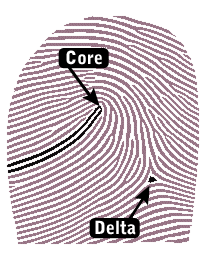

Dactyloscopy relies on the analysis and classification of patterns observed in individual prints. Fingerprints are made of series of ridges and furrows on the surface of a finger; the loops, whorls, and arches formed by those ridges and furrows generally follow a number of distinct patterns. Fingerprints also contain individual characteristics called “minutiae,” such as the number of ridges and their groupings, that are not perceptible to the unaided eye. The fingerprints left by people on objects that they have touched can be either visible or latent. Visible prints may be left behind by substances that stick to the fingers—such as dirt or blood—or they may take the form of an impression made in a soft substance, such as clay. Latent fingerprints are traces of sweat, oil, or other natural secretions on the skin, and they are not ordinarily visible. Latent fingerprints can be made visible by dusting techniques when the surface is hard and by chemical techniques when the surface is porous.

Fingerprints provide police with extremely strong physical evidence tying suspects to evidence or crime scenes. Yet, until the computerization of fingerprint records, there was no practical way of identifying a suspect solely on the basis of latent fingerprints left at a crime scene because police would not know which set of prints on file (if any) might match those left by the suspect. This changed in the 1980s when the Japanese National Police Agency established the first practical system for matching prints electronically. Today police in most countries use such systems, called automated fingerprint identification systems (AFIS), to search rapidly through millions of digitized fingerprint records. Fingerprints recognized by AFIS are examined by a fingerprint analyst before a positive identification or match is made.

Fingerprint identification, known as dactyloscopy, or hand print identification, is the process of comparing two instances of friction ridge skin impressions, from human fingers or toes, or even the palm of the hand or sole of the foot, to determine whether these impressions could have come from the same individual. The flexibility of friction ridge skin means that no two finger or palm prints are ever exactly alike in every detail; even two impressions recorded immediately after each other from the same hand may be slightly different. Fingerprint identification, also referred to as individualization, involves an expert, or an expert computer system operating under threshold scoring rules, determining whether two friction ridge impressions are likely to have originated from the same finger or palm (or toe or sole).

An intentional recording of friction ridges is usually made with black printer's ink rolled across a contrasting white background, typically a white card. Friction ridges can also be recorded digitally, usually on a glass plate, using a technique called Live Scan. A "latent print" is the chance recording of friction ridges deposited on the surface of an object or a wall. Latent prints are invisible to the unaided eye, whereas "patent prints" or "plastic prints" are viewable with the unaided eye. Latent prints are often fragmentary and require the use of chemical methods, powder, or alternative light sources in order to be made clear. Sometimes an ordinary bright flashlight will make a latent print visible.

When friction ridges come into contact with a surface that will take a print, material that is on the friction ridges such as perspiration, oil, grease, ink, or blood, will be transferred to the surface. Factors which affect the quality of friction ridge impressions are numerous. Pliability of the skin, deposition pressure, slippage, the material from which the surface is made, the roughness of the surface, and the substance deposited are just some of the various factors which can cause a latent print to appear differently from any known recording of the same friction ridges. Indeed, the conditions surrounding every instance of friction ridge deposition are unique and never duplicated. For these reasons, fingerprint examiners are required to undergo extensive training. The scientific study of fingerprints is called dermatoglyphics.

It appears to me that if one wants to make progress in mathematics, one should study the masters and not the pupils. - Niels Henrik Abel.

Nothing is better than reading and gaining more and more knowledge - Stephen William Hawking.

Offline

#547 2019-12-02 01:16:15

- Jai Ganesh

- Administrator

- Registered: 2005-06-28

- Posts: 52,479

Re: Miscellany

439) Python

Python, any of about 40 species of snakes, all but one of which are found in the Old World tropics and subtropics. Most are large, with the reticulated python (Python reticulatus) of Asia attaining a maximum recorded length of 9.6 metres (31.5 feet).

Eight species of genus Python live in sub-Saharan Africa and from India to southern China into Southeast Asia, including the Philippines and the Moluccas islands of Indonesia. Other related genera inhabit New Guinea and Australia. Some Australian pythons (genus Liasis) never grow much longer than one metre, but some pythons of Africa (P. sebae), India (P. molurus), New Guinea (L. papuanus), and Australia (L. amethistinus) regularly exceed 3 metres (10 feet). Despite their large size, some of these species survive in urban and suburban areas, where their secretive habits and recognized value as rat catchers par excellence serve to protect them.

Most pythons are terrestrial to semiarboreal, and a few, such as the green tree python (Morelia viridis) of Australia and New Guinea, are strongly arboreal. Terrestrial pythons are regularly found near water and are proficient swimmers, but they hunt and eat almost exclusively on land. Larger pythons prey mainly on mammals and birds; smaller species also eat amphibians and reptiles. Pythons have good senses of smell and sight, and most can also detect heat. Pits lying between the lip scales have receptors that are sensitive to infrared radiation and enable pythons to “see” the heat shadow of mammals and birds even during the darkest night. Prey is captured by striking and biting, usually followed by constriction. When swallowing prey, pythons secrete a mucus that contains harmless trace amounts of venom proteins.

Pythons are egg layers (oviparous) rather than live-bearers (viviparous). Females of most, if not all, species coil around the eggs, and some actually brood them. Brooders select thermally stable nesting sites, then lay their eggs and coil around them so that the eggs are in contact only with the female’s body. When the air temperature begins to drop, she generates heat by shivering in a series of minuscule muscle contractions and thus maintains an elevated and fairly constant incubation temperature.

Taxonomists divide the family Pythonidae into either four or eight genera. The only New World python (Loxocemus bicolor) is classified as the sole member of the family Loxocemidae. It is an egg layer found in forests from southern Mexico to Costa Rica. Usually less than 1 metre (3.3 feet) long, it is reported to reach nearly 1.5 metres (5 feet). It seems to be predominantly nocturnal, foraging on the ground for a variety of small vertebrates. The so-called earth, or burrowing, python (Calabaria reinhardtii or Charina reinhardtii) of West Africa appears to be a member of the boa family (Boidae).

Python Facts

Pythons are one of the largest snakes. Unlike many other snake species, pythons don’t produce venom - they are non-venomous snakes. Pythons live in the tropical areas of Africa and Asia. They can be found in rainforests, savannas and deserts. A lot of people keep them as pets. Pythons don’t attack humans, unless they are provoked or stressed.

Interesting Python Facts:

Pythons are constrictors. They kill their prey by squeezing them until they stop breathing.

After they kill an animal, they will swallow it in one piece.