Math Is Fun Forum

You are not logged in.

- Topics: Active | Unanswered

#626 2019-11-05 00:05:40

- Jai Ganesh

- Administrator

- Registered: 2005-06-28

- Posts: 51,610

Re: crème de la crème

592) Jarkko Oikarinen

Jarkko Oikarinen (born 16 August 1967) is a Finnish IT professional and the inventor of the first Internet chat network, called Internet Relay Chat (IRC), where he is known as WiZ.

Biography and career

Oikarinen was born in Kuusamo. While working at the University of Oulu in August 1988, he wrote the first IRC server and client programs, which he produced to replace the MUT (MultiUser Talk) program on the Finnish BBS OuluBox. Using the Bitnet Relay chat system as inspiration, Oikarinen continued to develop IRC over the next four years, receiving assistance from Darren Reed in co-authoring the IRC Protocol. In 1997, his development of IRC earned Oikarinen a Dvorak Award for Personal Achievement—Outstanding Global Interactive Personal Communications System; in 2005, the Millennium Technology Prize Foundation, a Finnish public-private partnership, honored him with one of three Special Recognition Awards.

He started working for medical image processing in 1990 in Oulu University Hospital, developing research software for neurosurgical workstation, and between 1993 and 1996 he worked for Elekta in Stockholm, Sweden and Grenoble, France putting the research into commercial products marketed by Elekta. In 1997 he returned to Oulu University Hospital to finish his Ph.D. as Joint Assistant Professor / Research Engineer, receiving the Ph.D. from the University of Oulu in 1999, in areas of computer graphics and medical imaging. During these years he focused on telemedicine, volume rendering, signal processing and computed axial tomography. Once finishing his Ph.D., he has held the positions of Chief Software Architect of Add2Phone Oy (Helsinki, Finland), Head of R&D in Capricode (Oulu, Finland) and General Manager in Nokia.

He is also partner and chief software architect at an electronic games developer called Numeric Garden (Espoo, Finland).

Oikarinen and his wife, Kaija-Leena, were married in 1996 and have three children: Kasper, Matleena, and Marjaana.

Oikarinen has been working for Google since 2011, initially in Stockholm, Sweden, and since 2016 in Kirkland, Washington. He is working on the Google Hangouts and Google Meet projects.

It appears to me that if one wants to make progress in mathematics, one should study the masters and not the pupils. - Niels Henrik Abel.

Nothing is better than reading and gaining more and more knowledge - Stephen William Hawking.

Offline

#627 2019-11-07 00:21:57

- Jai Ganesh

- Administrator

- Registered: 2005-06-28

- Posts: 51,610

Re: crème de la crème

593) Morita Akio

Morita Akio, (born Jan. 26, 1921, Nagoya, Japan—died Oct. 3, 1999, Tokyo), Japanese businessman who was cofounder, chief executive officer (from 1971), and chairman of the board (from 1976 through 1994) of Sony Corporation, world-renowned manufacturer of consumer electronics products.

Morita came from a family with a long tradition of sake brewing and was expected to follow in the family business. Instead he showed an early interest in technology, eventually attending Ōsaka Imperial University and graduating in 1944 with a degree in physics. During World War II he was assigned to the Air Armoury at Yokosuka, where he met Ibuka Masaru, industry’s representative on the Wartime Research Committee. Together the two men worked to develop thermal guidance systems and night-vision devices.

After the war Morita worked with Ibuka to establish a communications laboratory in Tokyo. In 1946 they cofounded Tokyo Telecommunications Engineering Corporation (Tōkyō Tsūshin Kōgyō), renamed Sony Corporation in 1958. Morita’s major concerns were the financial and business matters; he was responsible for marketing Sony products worldwide. Some of Morita and Ibuka’s product successes include early consumer versions of the tape recorder (1950; Ibuka had developed magnetic recording tape a year earlier), the transistorized radio (1955), and the “pocket-sized” transistor radio (1957).

Morita had a corporate vision that was global in scope. Indeed, the name Sony was chosen after the founders searched dictionaries trying to find a name that would be pronounceable in any language. (Sony was derived from the Latin sonus, “sound.”) In 1961, under Morita’s direction, Sony became the first Japanese company to sell its shares on the New York Stock Exchange. In addition, he moved himself and his family to the United States for a year in 1963 in order to better understand American business practices and American ways of thinking. Once Sony products began to sell well internationally, Morita opened factories in the United States and Europe in addition to those in Japan.

With Ibuka’s innovative consumer products and Morita’s business savvy, Sony became a major competitor in the electronics industry. Morita pioneered the concept of branding, making sure that the name Sony was prominent on all products and refusing to sell products to other businesses to be packaged under their labels. The corporation also used American-style advertising to great advantage. Frequently, however, Morita helped Sony to prosper by recognizing the potential in new products. It was at Morita’s urging that the Sony Walkman portable tape player was developed and marketed (company insiders doubted that there was enough consumer demand for the device). The Walkman was one of Sony’s most popular consumer products in the 1980s and ’90s.

Not all decisions made by Morita were so successful; the belief and determination he invested in winning products were sometimes invested in missteps as well. For instance, Sony was one of the first to release videocassette recorders (VCRs) for home use, but Sony’s version, Betamax (Beta), was soon overwhelmed by the more popular VHS version; it was some time before Morita was willing to allow Sony to shift to the industry standard of VHS. After the Beta problem, however, Morita concluded that Sony must forge partnerships with other electronics firms. Thus, when Sony developed the CD storage disk that would eventually revolutionize computer data storage and the music industry, it was done in partnership with the Dutch firm Philips Electronics NV to ensure that an industry standard for the product was achieved from the start.

As Sony’s stature grew, so did Morita’s in the international business community. He sat on a number of boards representing Japanese business. He was vice-chairman of the Keidanren (Japanese Federation of Economic Organizations), a group that has a powerful influence over decisions made by the Japanese government concerning business and economics. Morita also was a longtime member of the “Wise Men” (as the eight-member Japan–U.S. Economic Relations Group is informally called).

Morita was closely involved in the management of the Sony company until his retirement, owing to ill health, in 1994. His autobiography, Made in Japan: Akio Morita and Sony, was published in 1986.

It appears to me that if one wants to make progress in mathematics, one should study the masters and not the pupils. - Niels Henrik Abel.

Nothing is better than reading and gaining more and more knowledge - Stephen William Hawking.

Offline

#628 2019-11-09 00:14:47

- Jai Ganesh

- Administrator

- Registered: 2005-06-28

- Posts: 51,610

Re: crème de la crème

594) Adolphe Quetelet

Lambert Adolphe Jacques Quetelet (22 February 1796 – 17 February 1874 was a Belgian astronomer, mathematician, statistician and sociologist. He founded and directed the Brussels Observatory and was influential in introducing statistical methods to the social sciences. His name is sometimes spelled with an accent as Quételet. He founded the science of anthropometry and developed the body mass index scale, originally called the Quetelet Index.

Biography

Adolphe was born in Ghent (which, at the time was a part of the new French Republic). He was the son of François-Augustin-Jacques-Henri Quetelet, a Frenchman and Anne Françoise Vandervelde, a Flemish woman. His father was born at Ham, Picardy, and being of a somewhat adventurous spirit, he crossed the English Channel and became both a British citizen and the secretary of a Scottish nobleman. In that capacity, he traveled with his employer on the Continent, particularly spending time in Italy. At about 31, he settled in Ghent and was employed by the city, where Adolphe was born, the fifth of nine children, several of whom died in childhood.

Francois died when Adolphe was only seven years old. Adolphe studied at the Ghent Lycée, where he afterwards started teaching mathematics in 1815 at the age of 19. In 1819, he moved to the Athenaeum in Brussels and in the same year he completed his dissertation (De quibusdam locis geometricis, necnon de curva focal – Of some new properties of the focal distance and some other curves).

Quetelet received a doctorate in mathematics in 1819 from the University of Ghent. Shortly thereafter, the young man set out to convince government officials and private donors to build an astronomical observatory in Brussels; he succeeded in 1828. He became a member of the Royal Academy in 1820. He lectured at the museum for sciences and letters and at the Belgian Military School. In 1825, he became correspondent of the Royal Institute of the Netherlands, in 1827 he became member. From 1841 to 1851, he was supernumerary associate in the Institute, and when it became Royal Netherlands Academy of Arts and Sciences he became foreign member. In 1850, he was elected a foreign member of the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences.

Quetelet also founded several statistical journals and societies, and was especially interested in creating international cooperation among statisticians. He encouraged the creation of a statistical section of the British Association for the Advancement of Science (BA), which later became the Royal Statistical Society, of which he became the first overseas member.

In 1855, Quetelet suffered from apoplexy, which diminished but did not end his scientific activity.

He died in Brussels on 17 February 1874, and is buried in the Brussels Cemetery.

Family

In 1825, he married Cécile-Virginie Curtet.

Work

His scientific research encompassed a wide range of different scientific disciplines: meteorology, astronomy, mathematics, statistics, demography, sociology, criminology and history of science. He made significant contributions to scientific development, but he also wrote several monographs directed to the general public. He founded the Royal Observatory of Belgium, founded or co-founded several national and international statistical societies and scientific journals, and presided over the first series of the International Statistical Congresses. Quetelet was a liberal and an anticlerical, but not an atheist or materialist nor a socialist.

Social physics

The new science of probability and statistics was mainly used in astronomy at the time, where it was essential to account for measurement errors around means. This was done using the method of least squares. Quetelet was among the first to apply statistics to social science, planning what he called "social physics". He was keenly aware of the overwhelming complexity of social phenomena, and the many variables that needed measurement. His goal was to understand the statistical laws underlying such phenomena as crime rates, marriage rates etc. He wanted to explain the values of these variables by other social factors. These ideas were rather controversial among other scientists at the time who held that it contradicted the concept of freedom of choice.

His most influential book was Sur l'homme et le développement de ses facultés, ou Essai de physique sociale, published in 1835 (In English translation, it is titled Treatise on Man, but a literal translation would be "On Man and the Development of his Faculties, or Essays on Social Physics"). In it, he outlines the project of a social physics and describes his concept of the "average man" (l'homme moyen) who is characterized by the mean values of measured variables that follow a normal distribution. He collected data about many such variables.

Quetelet's student Pierre François Verhulst developed the logistic function in the 1830s as a model of population growth; see Logistic function History for details.

When Auguste Comte discovered that Quetelet had appropriated the term 'social physics', which Comte had originally introduced, Comte found it necessary to invent the term 'sociologie' (sociology) because he disagreed with Quetelet's notion that a theory of society could be derived from a collection of statistics.

Criminology

Quetelet was an influential figure in criminology. Along with Andre-Michel Guerry, he helped to establish the cartographic school and positivist schools of criminology which made extensive use of statistical techniques. Through statistical analysis, Quetelet gained insight into the relationships between crime and other social factors. Among his findings were strong relationships between age and crime, as well as gender and crime. Other influential factors he found included climate, poverty, education, and alcohol consumption, with his research findings published in Of the Development of the Propensity to Crime.

Anthropometry

In his 1835 text on social physics, in which he presented his theory of human variance around the average, with human traits being distributed according to a normal curve, he proposed that normal variation provided a basis for the idea that populations produce sufficient variation for artificial or natural selection to operate.

In terms of influence over later public health agendas, one of Quetelet's lasting legacies was the establishment of a simple measure for classifying people's weight relative to an ideal for their height. His proposal, the body mass index (or Quetelet index), has endured with minor variations to the present day. Anthropometric data is used in modern applications and referenced in the development of every consumer-based product.

Awards and honours

Quetelet was elected a Foreign Member of the Royal Society (ForMemRS) in 1839.

The asteroid 1239 Queteleta is named after him. The title of Quetelet professor at Columbia University is awarded in his name.

It appears to me that if one wants to make progress in mathematics, one should study the masters and not the pupils. - Niels Henrik Abel.

Nothing is better than reading and gaining more and more knowledge - Stephen William Hawking.

Offline

#629 2019-11-11 00:11:23

- Jai Ganesh

- Administrator

- Registered: 2005-06-28

- Posts: 51,610

Re: crème de la crème

595) Forrest Parry

Forrest Corry Parry (July 4, 1921 – December 31, 2005) was the IBM engineer who invented the Magnetic stripe card used for Credit cards and identification badges.

Parry was born in Cedar City, Utah to Edward H. Parry and Marguerite C. Parry. Forrest attended the Branch Agricultural College (BAC) now Southern Utah University, in Cedar City before entering the U.S. Naval Academy at Annapolis, Md, in 1942. He graduated from the Naval Academy in June 1945. When the Korean War began in 1950, Parry served on the USS Walke as First Lieutenant and Damage Control Officer. After the Walke was hit by a torpedo or floating mine which killed 26 sailors and wounded 40, Parry was awarded a Bronze Star with Valor.

Career

After leaving the Navy in 1952, Parry went to work at Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory and married Dorothea Tillia. They raised five children. Parry left Livermore in 1954 to work for Dow Chemical and then at Unette Corporation, a small plastic packaging firm.

In May 1957, Parry began his 30-year career with IBM, mostly in Rochester, Minnesota. While at IBM, he developed devices and systems for high-speed printers, optical character readers, Universal Product Code (UPC) checkout systems, and an Advanced Optical Character Reader (AOCR) which reads addresses from mailed letters and reprints it as bar codes for easy resorting at smaller post offices that have simpler and cheaper sorting machines.

In 1960, while at IBM, Parry invented the magnetic stripe card for use by the U.S. Government. He had the idea of gluing short pieces of magnetic tape to each plastic card, but the glue warped the tape, making it unusable. When he returned home, Parry's wife Dorothea was using a flat iron to iron clothes. When he explained his inability to get the tape to "stick" to the plastic in a way that would work, she suggested that he use the iron to melt the stripe onto the card. He tried it and it worked. The heat of the iron was just high enough to bond the tape to the card. Magnetic stripes are now used on credit cards, debit cards, gift cards, stored-value cards, hotel keycards, and security identification badges.

It appears to me that if one wants to make progress in mathematics, one should study the masters and not the pupils. - Niels Henrik Abel.

Nothing is better than reading and gaining more and more knowledge - Stephen William Hawking.

Offline

#630 2019-11-13 00:18:59

- Jai Ganesh

- Administrator

- Registered: 2005-06-28

- Posts: 51,610

Re: crème de la crème

596) Petrache Poenaru

Petrache Poenaru (1799–1875) was a Romanian inventor of the Enlightenment era.

Poenaru, who had studied in Paris and Vienna and, later, completed his specialized studies in England, was a mathematician, physicist, engineer, inventor, teacher and organizer of the educational system, as well as a politician, agronomist, and zootechnologist, founder of the Philharmonic Society, the Botanical Gardens and the National Museum of Antiquities in Bucharest.

While a student in Paris, Petrache Poenaru invented the world's first fountain pen, an invention for which the French Government issued a patent on 25 May 1827.

Biography

He was born in 1799 in Băneşti, Vâlcea County. His uncle, Iordache Otetelişanu, was one of the promoters of an institutionalized educational system, in a time when a great part of the population was illiterate. Poenaru attended the secondary school Obedeanu in Craiova and worked as a copyist at the office of the bishop of Râmnicu Vâlcea. Later on, between 1820 and 1821, he taught Greek language at the Metropolitan School in Bucharest.

In 1821, the Revolution led by Tudor Vladimirescu began. At that time, Wallachia was under Turkish domination and was ruled by the Phanariots (Greeks originating from Constantinople and very loyal to the Sultan), who burdened the country with numerous taxes and an expensive and corrupt court. Tudor Vladimirescu gathered an army of Oltenian soldiers called panduri and moved towards Bucharest to overthrow them. He was joined by many and, among them, was the young Petrache Poenaru. During his first skirmish, he proved he didn’t have any fighting abilities and his comrades took him in front of the revolution’s leader, for punishment. But Vladimirescu was impressed by the young man’s educated spirit and sharp mind and made him his personal assistant. From this position, he elaborated the army’s manifesto, now considered one of the first Romanian newspapers.

Poenaru was lucky enough not to be around Tudor Vladimirescu when the leader was lured in a trap and assassinated, as he was sent in a diplomatic mission to advocate the Romanian cause to the representatives of the great powers, Russia, Austria or England. After news of Vladimirescu’s death spread, he took refuge in Sibiu.

When the political situation improved, he was able to earn a scholarship to study in Vienna, in 1822. There, he learnt about measuring tools and micrometers, unknown to the underdeveloped Romanian engineering field and discovered a great appetite for technical sciences, while also fervently studying Greek, Latin, French, Italian and English. In a letter sent to his family, he confessed that he thought the sweetest pleasure a man can experience is learning.

In 1824, the Wallachian ruler Grigore Ghica granted him another scholarship, which compelled Poenaru to return to the country after the studies ended and share his acquired knowledge as a teacher.

Poenaru's fountain pen

In 1826 he went to France and attended the École Polytechnique in Paris, where he studied geodesy and surveying. He was so busy taking notes and copying courses, that he invented a fountain pen that used a swan's quill as an ink reservoir. On 25 May 1827, the Manufacture Department of the French Ministry of the Interior registered Poenaru’s invention with the code number 3208 and the description ”plume portable sans fin, qui s’alimente elle-meme avec de l’ancre" ("never-ending portable pen, which recharges itself with ink").

It appears to me that if one wants to make progress in mathematics, one should study the masters and not the pupils. - Niels Henrik Abel.

Nothing is better than reading and gaining more and more knowledge - Stephen William Hawking.

Offline

#631 2019-11-15 00:28:44

- Jai Ganesh

- Administrator

- Registered: 2005-06-28

- Posts: 51,610

Re: crème de la crème

597) Charlie Chaplin

Charlie Chaplin, byname of Sir Charles Spencer Chaplin, (born April 16, 1889, London, England—died December 25, 1977, Corsier-sur-Vevey, Switzerland), British comedian, producer, writer, director, and composer who is widely regarded as the greatest comic artist of the screen and one of the most important figures in motion-picture history.

Early Life And Career

Chaplin was named after his father, a British music-hall entertainer. He spent his early childhood with his mother, the singer Hannah Hall, after she and his father separated, and he made his own stage debut at age five, filling in for his mother. The mentally unstable Hall was later confined to an asylum. Charlie and his half brother Sydney were sent to a series of bleak workhouses and residential schools.

Using his mother’s show-business contacts, Charlie became a professional entertainer in 1897 when he joined the Eight Lancashire Lads, a clog-dancing act. His subsequent stage credits include a small role in William Gillette’s Sherlock Holmes (1899) and a stint with the vaudeville act Casey’s Court Circus. In 1908 he joined the Fred Karno pantomime troupe, quickly rising to star status as The Drunk in the ensemble sketch A Night in an English Music Hall.

While touring America with the Karno company in 1913, Chaplin was signed to appear in Mack Sennett’s Keystone comedy films. Though his first Keystone one-reeler, Making a Living (1914), was not the failure that historians have claimed, Chaplin’s initial screen character, a mercenary dandy, did not show him to best advantage. Ordered by Sennett to come up with a more-workable screen image, Chaplin improvised an outfit consisting of a too-small coat, too-large pants, floppy shoes, and a battered derby. As a finishing touch, he pasted on a postage-stamp mustache and adopted a cane as an all-purpose prop. It was in his second Keystone film, Kid Auto Races at Venice (1914), that Chaplin’s immortal screen alter ego, “the Little Tramp,” was born.

In truth, Chaplin did not always portray a tramp; in many of his films his character was employed as a waiter, store clerk, stagehand, fireman, and the like. His character might be better described as the quintessential misfit—shunned by polite society, unlucky in love, jack-of-all-trades but master of none. He was also a survivor, forever leaving past sorrows behind, jauntily shuffling off to new adventures. The Tramp’s appeal was universal: audiences loved his cheekiness, his deflation of pomposity, his casual savagery, his unexpected gallantry, and his resilience in the face of adversity. Some historians have traced the Tramp’s origins to Chaplin’s Dickinson childhood, while others have suggested that the character had its roots in the motto of Chaplin’s mentor, Fred Karno: “Keep it wistful, gentlemen, keep it wistful.” Whatever the case, within months after his movie debut, Chaplin was the screen’s biggest star.

His 35 Keystone comedies can be regarded as the Tramp’s gestation period, during which a caricature became a character. The films improved steadily once Chaplin became his own director. In 1915 he left Sennett to accept a $1,250-weekly contract at Essanay Studios. It was there that he began to inject elements of pathos into his comedy, notably in such shorts as The Tramp (1915) and Burlesque on Carmen (1915). He moved on to an even more lucrative job ($670,000 per year) at the Mutual Company Film Corporation. There, during an 18-month period, he made the 12 two-reelers that many regard as his finest films, among them such gems as One A.M. (1916), The Rink (1916), The Vagabond (1916), and Easy Street (1917). It was then, in 1917, that Chaplin found himself attacked for the first (though hardly the last) time by the press. He was criticized for not enlisting to fight in World War I. To aid the war effort, Chaplin raised funds for the troops via bond drives.

In 1918 Chaplin jumped studios again, accepting a $1 million offer from the First National Film Corporation for eight shorts. That same year he married 16-year-old film extra Mildred Harris—the first in a procession of child brides. For his new studio he made shorts such as Shoulder Arms (1918) and The Pilgrim (1923) and his first starring feature, The Kid (1921), which starred the irresistible Jackie Coogan as the kid befriended and aided by the Little Tramp. Some have suggested that the increased dramatic content of those films is symptomatic of Chaplin’s efforts to justify the praise lavished upon him by the critical intelligentsia. A painstaking perfectionist, he began spending more and more time on the preparation and production of each film. In his personal life too, Chaplin was particular. Having divorced Mildred in 1921, Chaplin married in 1924 16-year-old Lillita MacMurray, who shortly would become known to the world as film star Lita Grey. (They would be noisily divorced in 1927.)

From 1923 through 1929 Chaplin made only three features: A Woman of Paris (1923), which he directed but did not star in (and his only drama); The Gold Rush (1925), widely regarded as his masterpiece; and The Circus (1928), an underrated film that may rank as his funniest. All three were released by United Artists, the company cofounded in 1919 by Chaplin, husband-and-wife superstars Douglas Fairbanks and Mary Pickford, and director D.W. Griffith. Of the three films, The Gold Rush is one of the most-memorable films of the silent era. Chaplin placed the Little Tramp in the epic setting of the Yukon, amid bears, snowstorms, and a fearsome prospector (Mack Swain); his love interest was a beautiful dance-hall queen (Georgia Hale). The scene in which the Tramp must eat his shoe to stay alive epitomizes the film’s blend of rich comedy and well-earned pathos.

The Sound Era: City Lights To Limelight

As the Little Tramp, Chaplin had mastered the subtle art of pantomime, and the advent of sound gave him cause for alarm. After much hesitation, he released his 1931 feature City Lights as a silent, despite the ubiquity of talkies after 1929. It was a sweet, unabashedly sentimental story in which the Little Tramp falls in love with a blind flower girl (Virginia Cherrill) and he vows to restore her sight. The musical score, the lone “sound” element the film offered, was composed by Chaplin, and he conducted its recording; no matter the lack of dialogue, it was a huge success.

In 1932 Chaplin began a relationship with young starlet Paulette Goddard. His next film, Modern Times (1936), was a hybrid, essentially a silent film with music, sound effects, and brief passages of dialogue. Chaplin also gave his Little Tramp a voice, as he performed a gibberish song. Chaplin played a nameless factory worker who has been dehumanized by the mindless task he has to perform—tightening bolts on parts that fly by on an assembly line; Goddard played “A Gamin,” the waif who comes under his wing. It was the last silent feature to come out of Hollywood, but audiences still turned out to see it. Most significantly, it was the Little Tramp’s final performance.

The Great Dictator (1940) was Chaplin’s most overt political satire and his first sound picture. Chaplin starred in a dual role as a nameless Jewish barber and as Adenoid Hynkel, Dictator of Tomania—a dead-on parody of German dictator Adolf Hitler, to whom Chaplin bore a remarkable physical resemblance. Goddard played Hannah, the barber’s Jewish friend, who flees Tomania after the barber is arrested and sent to a concentration camp, and Jack Oakie gave a hilarious impersonation of Italian dictator Benito Mussolini as Napaloni, Dictator of Bacteria. The japing tone of the picture’s lampooning was a movement away from Chaplin’s usual poetic approach; The Great Dictator was simply too bitter and too outraged to permit much in the way of gentle comedy. The film did well at the box office, and he received his only Academy Award nomination as best actor.

After making just three movies over a 10-year period, Chaplin would take seven more years before his next film. Problems in his personal life were again partly to blame. In 1942 he and Goddard divorced (despite likely never having officially married). In 1943 a paternity suit was brought against him by young would-be actress Joan Barry. That same year he married 18-year-old Oona O’Neill, daughter of playwright Eugene O’Neill; again he was accused of cradle robbing. In the Barry suit the courts ruled against Chaplin in 1944; he was named the father of Barry’s child, although he was cleared of the more serious charges of violating the Mann Act, which prohibited interstate transportation of women for “immoral purposes.”

His darkest comedy, Monsieur Verdoux, was released in 1947, and by then Chaplin was in the headlines again, as possibly being called before the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC) to testify about his relations with communists, especially exiled German composer Hanns Eisler. Chaplin starred in that “Comedy of Murders” (as Monsieur Verdoux was promoted) as Henri Verdoux, a happily married father and former bank clerk who becomes the scourge of 1930s Paris by romancing and then killing a series of rich widows and spinsters for their fortunes. (Chaplin’s character was based on French murderer Henri Landru, who was known as the Bluebeard of France when he went on his killing spree during the 1910s.) Monsieur Verdoux was an utter failure commercially upon its release—his first since A Woman of Paris 24 years earlier—and critical opinion was divided, although Chaplin’s screenplay was nominated for an Oscar. It is still difficult to determine whether Monsieur Verdoux would have been better received had he not been suffering from the attentions of HUAC. When Chaplin heard news that he would be summoned before the committee, he immediately accepted, saying, “I am not a communist. I am a peacemonger.” He planned a rerelease of Monsieur Verdoux in Washington, D.C., for the week Eisler was to testify before HUAC, and he invited the committee members to the premiere. However, HUAC chairman J. Parnell Roberts canceled Chaplin’s appearance and said he would not be a part of publicity for Monsieur Verdoux.

Chaplin took another five years to launch his next film, the melancholy Limelight (1952). He played Calvero, a music-hall idol whose day has passed, and British actress Claire Bloom (then 19) costarred as Terry, a ballet dancer whom Calvero saves from a suicide attempt; he shelters, encourages, and finally helps elevate her to the top of her profession, even as his own star dims and then blinks out. Chaplin’s half brother Sydney and his son Charlie, Jr., both had small parts, and silent comedy star Buster Keaton had a key role as a theatre pianist who watches Calvero expire. (Limelight would be given an Oscar for its score, to which Chaplin contributed, in 1973, after the film finally received the requisite release in Los Angeles.)

For Chaplin, Limelight’s release was further tainted by the U.S. Immigration and Naturalization Service advising him (as he sailed on an ocean liner with Oona to the film’s premiere in London) that he would be denied reentry to the United States unless he was willing to answer charges “of a political nature and of moral turpitude.” The Chaplins continued on their way to England; she returned to the States to close out their business affairs, while he kept going, finally settling in Corsier-sur-Vevey, Switzerland, where he and Oona would live for the rest of their lives. He liquidated his interest in United Artists.

Final Works: A King In New York And A Countess From Hong Kong

Chaplin made use of his own experiences as a victim of McCarthyism in his next film, the British-made A King in New York (1957). Satirizing the very witch hunts that had sent him into self-imposed exile, Chaplin fashioned a diatribe against the foibles of 1950s America that only occasionally managed to nail its target. (Ironically, the film was not released in the United States until 1973.)

While an anthology titled The Chaplin Revue (comprising the shorts A Dog’s Life [1918], Shoulder Arms [1918], and The Pilgrim [1923]) was being given a theatrical release in the United States in 1959, Chaplin began work on his memoirs. My Autobiography (1964) provided a great deal of information about Chaplin’s childhood and rise to stardom but was less forthcoming about his work and adult life. Nevertheless, the warm reception it was accorded made another film project viable.

The passing of a full decade since A King in New York and the radical change in the political climate of the United States ensured that there was much anticipation surrounding A Countess from Hong Kong (1967), a British-made romantic comedy starring Marlon Brando and Sophia Loren, the biggest names he had worked with since he himself was a premier box-office draw. However, it proved to be a critical and commercial disappointment.

In his last years Chaplin was accorded many of the honours that had been withheld from him for so long. In 1972 he returned to the United States for the first time in 20 years to accept a special Academy Award for “the incalculable effect he has had on making motion pictures the art form of this century.” It was a bittersweet homecoming. Chaplin had come to deplore the United States, but he was visibly and deeply moved by the 12-minute standing ovation he received at the Oscar ceremonies. As Alistair Cooke described the events,

He was very old and trembly and groping through the thickening fog of memory for a few simple sentences. A senile, harmless doll, he was now—as the song says—“easy to love,” absolutely safe to admire.

Chaplin made one of his final public appearances in 1975, when he was knighted. Several months after his death, his body was briefly kidnapped from a Swiss cemetery by a pair of bungling thieves—a macabre coda that Chaplin might have concocted for one of his own two-reelers.

It appears to me that if one wants to make progress in mathematics, one should study the masters and not the pupils. - Niels Henrik Abel.

Nothing is better than reading and gaining more and more knowledge - Stephen William Hawking.

Offline

#632 2019-11-17 00:09:31

- Jai Ganesh

- Administrator

- Registered: 2005-06-28

- Posts: 51,610

Re: crème de la crème

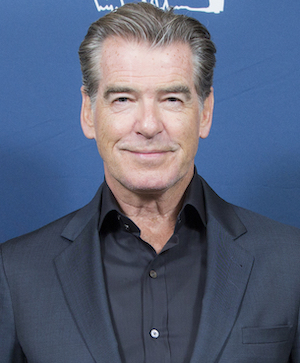

598) Pierce Brosnan

Pierce Brosnan , in full Pierce Brendan Brosnan, (born May 16, 1953, County Meath, Ireland), Irish American actor who was perhaps best known for playing James Bond in a series of films.

Brosnan, whose father left home shortly after his birth, was raised by relatives after his mother left to work in England. At age 15 he set out on his own in London to be an actor. He joined a theatre group and later studied at the Drama Centre of London. He married actress Cassandra Harris, and the two subsequently moved to the United States; he became a U.S. citizen in 2004. Brosnan was soon cast as a charming con man in the NBC television detective series Remington Steele. The show, which premiered in 1982, was a success, and in 1986 he was chosen as the successor to Roger Moore as James Bond—the suave British secret service agent 007 created by novelist Ian Fleming. His NBC contract, however, prevented him from accepting, and Timothy Dalton took the role instead. Remington Steele ended in 1987, and Brosnan continued to take on television and film roles. In 1991 he dealt with the loss of his wife, who died after a four-year battle with ovarian cancer.

Meanwhile, Dalton’s two Bond films were seen as relative failures, and in 1994 Brosnan was finally able to accept the role. His first film in the series, GoldenEye (1995), made more than $350 million worldwide, the most ever for a Bond film at that time. The second, Tomorrow Never Dies (1997), scored record grosses for a Bond film in the United States. Brosnan brought out the human side of the Bond character, and the series producers sought to emphasize that in The World Is Not Enough (1999). Brosnan made his final appearance as James Bond in Die Another Day (2002).

While making the Bond films, Brosnan expanded his repertoire and took advantage of his popularity to choose new projects. In 1999 he produced and starred in a remake of the 1968 film The Thomas Crown Affair. He later appeared in the espionage-thriller The Tailor of Panama (2001), a film adaptation of John le Carré’s novel; the romantic comedy Laws of Attraction (2004); and The Matador (2005), in which he played a weary hit man. In 2007 Brosnan starred opposite Liam Neeson in the Civil War film Seraphim Falls. The following year he appeared with Meryl Streep and Colin Firth in Mamma Mia!, a musical featuring songs by the Swedish pop group ABBA. Brosnan later reprised his role in the sequel, Mamma Mia! Here We Go Again (2018).

Brosnan’s subsequent movies included the children’s fantasy Percy Jackson and the Olympians: The Lightning Thief (2010) and Roman Polanski’s The Ghost Writer (2010), in which he played a former British prime minister accused of war crimes. In 2011 he appeared as a flirtatious businessman in the comedy I Don’t Know How She Does It and as a widowed writer in the TV miniseries Bag of Bones, which was based on a Stephen King novel. Brosnan then took a leading role in Love Is All You Need (2012), a romantic comedy set in Europe with a mainly Danish cast. In 2014 he featured in the ensemble cast of the drama A Long Way Down, based on the novel by Nick Hornby about four suicidal people, and in the thriller The November Man, in which he portrayed a retired CIA agent who is pulled onto a high-stakes mission. The next year Brosnan appeared in No Escape as an undercover British agent who assists a family in escaping from a fictional Asian country in the midst of a coup. In 2017 he starred opposite Jackie Chan in the revenge thriller The Foreigner. Brosnan portrayed a powerful Texas rancher in the television series The Son (2017– ).

It appears to me that if one wants to make progress in mathematics, one should study the masters and not the pupils. - Niels Henrik Abel.

Nothing is better than reading and gaining more and more knowledge - Stephen William Hawking.

Offline

#633 2019-11-19 00:18:56

- Jai Ganesh

- Administrator

- Registered: 2005-06-28

- Posts: 51,610

Re: crème de la crème

599) Bill Gates

Bill Gates, in full William Henry Gates III, (born October 28, 1955, Seattle, Washington, U.S.), American computer programmer and entrepreneur who cofounded Microsoft Corporation, the world’s largest personal-computer software company.

Gates wrote his first software program at the age of 13. In high school he helped form a group of programmers who computerized their school’s payroll system and founded Traf-O-Data, a company that sold traffic-counting systems to local governments. In 1975 Gates, then a sophomore at Harvard University, joined his hometown friend Paul G. Allen to develop software for the first microcomputers. They began by adapting BASIC, a popular programming language used on large computers, for use on microcomputers. With the success of this project, Gates left Harvard during his junior year and, with Allen, formed Microsoft. Gates’s sway over the infant microcomputer industry greatly increased when Microsoft licensed an operating system called MS-DOS to International Business Machines Corporation—then the world’s biggest computer supplier and industry pacesetter—for use on its first microcomputer, the IBM PC (personal computer). After the machine’s release in 1981, IBM quickly set the technical standard for the PC industry, and MS-DOS likewise pushed out competing operating systems. While Microsoft’s independence strained relations with IBM, Gates deftly manipulated the larger company so that it became permanently dependent on him for crucial software. Makers of IBM-compatible PCs, or clones, also turned to Microsoft for their basic software. By the start of the 1990s he had become the PC industry’s ultimate kingmaker.

Largely on the strength of Microsoft’s success, Gates amassed a huge paper fortune as the company’s largest individual shareholder. He became a paper billionaire in 1986, and within a decade his net worth had reached into the tens of billions of dollars—making him by some estimates the world’s richest private individual. With few interests beyond software and the potential of information technology, Gates at first preferred to stay out of the public eye, handling civic and philanthropic affairs indirectly through one of his foundations. Nevertheless, as Microsoft’s power and reputation grew, and especially as it attracted the attention of the U.S. Justice Department’s antitrust division, Gates, with some reluctance, became a more public figure. Rivals (particularly in competing companies in Silicon Valley) portrayed him as driven, duplicitous, and determined to profit from virtually every electronic transaction in the world. His supporters, on the other hand, celebrated his uncanny business acumen, his flexibility, and his boundless appetite for finding new ways to make computers and electronics more useful through software.

All of these qualities were evident in Gates’s nimble response to the sudden public interest in the Internet. Beginning in 1995 and 1996, Gates feverishly refocused Microsoft on the development of consumer and enterprise software solutions for the Internet, developed the Windows CE operating system platform for networking noncomputer devices such as home televisions and personal digital assistants, created the Microsoft Network to compete with America Online and other Internet providers, and, through Gates’s company Corbis, acquired the huge Bettmann photo archives and other collections for use in electronic distribution.

In addition to his work at Microsoft, Gates was also known for his charitable work. With his wife, Melinda, he launched the William H. Gates Foundation (renamed the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation in 1999) in 1994 to fund global health programs as well as projects in the Pacific Northwest. During the latter part of the 1990s, the couple also funded North American libraries through the Gates Library Foundation (renamed Gates Learning Foundation in 1999) and raised money for minority study grants through the Gates Millennium Scholars program. In June 2006 Warren Buffett announced an ongoing gift to the foundation, which would allow its assets to total roughly $60 billion in the next 20 years. At the beginning of the 21st century, the foundation continued to focus on global health and global development, as well as community and education causes in the United States. After a short transition period, Gates relinquished day-to-day oversight of Microsoft in June 2008—although he remained chairman of the board—in order to devote more time to the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation. In February 2014 he stepped down as chairman but continued to serve as a board member. Two years later he was awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom. The documentary series ‘Inside Bill’s Brain: Decoding Bill Gates’ appeared in 2019.

It remains to be seen whether Gates’s extraordinary success will guarantee him a lasting place in the pantheon of great Americans. At the very least, historians seem likely to view him as a business figure as important to computers as John D. Rockefeller was to oil. Gates himself displayed an acute awareness of the perils of prosperity in his 1995 best seller, ‘The Road Ahead’, where he observed, “Success is a lousy teacher. It seduces smart people into thinking they can’t lose.”

It appears to me that if one wants to make progress in mathematics, one should study the masters and not the pupils. - Niels Henrik Abel.

Nothing is better than reading and gaining more and more knowledge - Stephen William Hawking.

Offline

#634 2019-11-21 00:44:11

- Jai Ganesh

- Administrator

- Registered: 2005-06-28

- Posts: 51,610

Re: crème de la crème

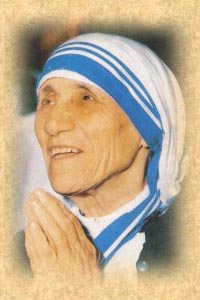

600) Mother Teresa

Mother Teresa, in full St. Teresa of Calcutta, also called St. Mother Teresa, original name Agnes Gonxha Bojaxhiu, (baptized August 27, 1910, Skopje, Macedonia, Ottoman Empire [now in Republic of Macedonia]—died September 5, 1997, Calcutta [now Kolkata], India; canonized September 4, 2016; feast day September 5), founder of the Order of the Missionaries of Charity, a Roman Catholic congregation of women dedicated to the poor, particularly to the destitute of India. She was the recipient of numerous honours, including the 1979 Nobel Prize for Peace.

The daughter of an ethnic Albanian grocer, she went to Ireland in 1928 to join the Sisters of Loretto at the Institute of the Blessed Virgin Mary and sailed only six weeks later to India as a teacher. She taught for 17 years at the order’s school in Calcutta (Kolkata).

In 1946 Sister Teresa experienced her “call within a call,” which she considered divine inspiration to devote herself to caring for the sick and poor. She then moved into the slums she had observed while teaching. Municipal authorities, upon her petition, gave her a pilgrim hostel, near the sacred temple of Kali, where she founded her order in 1948. Sympathetic companions soon flocked to her aid. Dispensaries and outdoor schools were organized. Mother Teresa adopted Indian citizenship, and her Indian nuns all donned the sari as their habit. In 1950 her order received canonical sanction from Pope Pius XII, and in 1965 it became a pontifical congregation (subject only to the pope). In 1952 she established Nirmal Hriday (“Place for the Pure of Heart”), a hospice where the terminally ill could die with dignity. Her order also opened numerous centres serving the blind, the aged, and the disabled. Under Mother Teresa’s guidance, the Missionaries of Charity built a leper colony, called Shanti Nagar (“Town of Peace”), near Asansol, India.

In 1962 the Indian government awarded Mother Teresa the Padma Shri, one of its highest civilian honours, for her services to the people of India. Pope Paul VI on his trip to India in 1964 gave her his ceremonial limousine, which she immediately raffled to help finance her leper colony. She was summoned to Rome in 1968 to found a home there, staffed primarily with Indian nuns. In recognition of her apostolate, she was honoured on January 6, 1971, by Pope Paul, who awarded her the first Pope John XXIII Peace Prize. In 1979 she received the Nobel Peace Prize for her humanitarian work, and the following year the Indian government conferred on her the Bharat Ratna, the country’s highest civilian honour.

In her later years Mother Teresa spoke out against divorce, contraception, and abortion. She also suffered ill health and had a heart attack in 1989. In 1990 she resigned as head of the order but was returned to office by a nearly unanimous vote—the lone dissenting voice was her own. A worsening heart condition forced her retirement, and the order chose the Indian-born Sister Nirmala as her successor in 1997. At the time of Mother Teresa’s death, her order included hundreds of centres in more than 90 countries with some 4,000 nuns and hundreds of thousands of lay workers. Within two years of her death, the process to declare her a saint was begun, and Pope John Paul II issued a special dispensation to expedite the process of canonization. She was beatified on October 19, 2003, reaching the ranks of the blessed in what was then the shortest time in the history of the church. She was canonized by Pope Francis I on September 4, 2016.

Although Mother Teresa displayed cheerfulness and a deep commitment to God in her daily work, her letters (which were collected and published in 2007) indicate that she did not feel God’s presence in her soul during the last 50 years of her life. The letters reveal the suffering she endured and her feeling that Jesus had abandoned her at the start of her mission. Continuing to experience a spiritual darkness, she came to believe that she was sharing in Christ’s Passion, particularly the moment in which Christ asks, “My God, my God, why have you forsaken me?” Despite this hardship, Mother Teresa integrated the feeling of absence into her daily religious life and remained committed to her faith and her work for Christ.

It appears to me that if one wants to make progress in mathematics, one should study the masters and not the pupils. - Niels Henrik Abel.

Nothing is better than reading and gaining more and more knowledge - Stephen William Hawking.

Offline

#635 2019-11-23 00:24:14

- Jai Ganesh

- Administrator

- Registered: 2005-06-28

- Posts: 51,610

Re: crème de la crème

601) Smithson Tennant

(b. Selby, Yorkshire, England, 30 November 1761; d. Boulogne, France, 22 February 1815)

Tennant’s father was the Reverend Calvert Tennant, a fellow of St. John’s College, Cambridge, and later vicar of Selby; his mother, Mary Daunt Tennant, was the daughter of an apothecary. Both parents had died by the time he was twenty, leaving him an inheritance of land. During 1781 he was a medical student at Edinburgh, where he attended Joseph Black’s lectures. In October 1782, he moved to Christ’s College, Cambridge, from which he received the M.B. in 1788 and the M.D. in 1796. He was elected fellow of the Royal Society in January 1785 and received the Copley Medal in 1804. In 1799 he was a founding member of the Askesian Society, which soon became the Geological Society. In 1813 he was appointed professor of chemistry at Cambridge. Tennant’s travels included a visit to Sweden in 1784, where he met Scheele and Gahn, and a journey to France in 1814–1815 that ended in a fatal riding accident.

Tennant wrote little and consequently was accused of indolence. In 1796 he communicated to the Royal Society his study of the combustion of the diamond. Lavoisier had carried out a series of similar experiments and observed that the gaseous product turned limewater cloudy, as in the burning of charcoal. However, he maintained that this common result merely showed that both charcoal and diamond were in the class of combustibles. Reluctant to stress the analogy further, Lavoisier even wrote that the nature of diamond might never be known. But Tennant insisted that since equal quantities of charcoal and diamond were entirely converted in combustion to equal quantities of fixed air, then both substances must be chemically identical. Certain scientists, notably Humphry Davy, continued to suspect that there were minute chemical differences between these forms of carbon; but Davy soon returned to the interpretation first given by Tennant.

Tennant’s most important work, the discovery of two new elements in platinum ore, was described in a paper to the Royal Society in 1804. The extraction of pure, malleable platinum from its crude ore was a problem that taxed eighteenth-century chemists. A notebook preserved at Cambridge on Tennant’s travels shows that he had discussed the problem with Gahn and Crell in 1784. At that time the standard procedure was to digest the crude ore in aqua regia; this technique left an insoluble black residue that Proust mistook for graphite. At about the same time Collet-Descotils, Fourcroy, Vauquelin, and Tennant realized that this residue contained something new. Collet-Descotils inferred the existence of a new metal from the red color it gave to platinum precipitates; Fourcroy and Vauquelin called the new metal ptáne but soon admitted that they had confused two different metals. Tennant alone recognized that the black powder contained two new metals, which he proceeded to isolate and characterize. He called one iridium on account of the variety of colors it produced; the other he named osmium because of the distinctive odor of its volatile compounds.

Tennant had interested William Wollaston in platinum while they were students at Cambridge. By 1800 they had became business partners, selling platinum boilers for the concentration of sulfuric acid and other products made of platinum.

It appears to me that if one wants to make progress in mathematics, one should study the masters and not the pupils. - Niels Henrik Abel.

Nothing is better than reading and gaining more and more knowledge - Stephen William Hawking.

Offline

#636 2019-11-25 00:09:10

- Jai Ganesh

- Administrator

- Registered: 2005-06-28

- Posts: 51,610

Re: crème de la crème

602) Tadeus Reichstein

adeus Reichstein was born on July 20th, 1897, at Wloclawek, Poland. He was the son of Isidor Reichstein and Gastava Brockmann. After passing his early childhood at Kiev, where his father was an engineer, Reichstein was educated, first at a boarding-school at Jena and later, when his family moved to Zurich (where he was naturalized), he first went to a private tutor and later to the Oberrealschule (technical school of junior college grade) and the Eidgenössische Technische Hochschule (E.T.H.) (State Technical College).

In 1916 Reichstein passed his school-leaving examination and began to study chemistry at the E.T.H. at Zurich, taking his diploma there in 1920. He then spent a year in industry and then began to work for his doctorate under Professor H. Staudinger. In 1922 he graduated and then began research under Professor Staudinger on the composition of the flavouring substances in roasted coffee.

After leaving Professor Staudinger, he continued to work for nine years on this subject, being financed for this purpose by an industrial firm, who provided him with an assistant. The aroma of coffee is, he found, composed of extremely complex substances, among which are derivatives of furan and pyrrole, and substances containing sulphur. Reichstein published during this period a series of papers on these substances and on new methods of demonstrating and making them, and also on the aromatic substances in chicory.

In 1929 he qualified as a lecturer at the E.T.H. Here he lectured on organic and physiological chemistry and in 1931, when his work on aromatic substances in coffee and chicory ended, he became assistant to Professor L. Ruzicka and was then able to devote himself exclusively to scientific research.

In 1934 he was appointed Titular Professor, in 1937 Associate Professor, and in 1938 Professor in Pharmaceutical Chemistry, and Director of the Pharmaceutical Institute in the University of Basel. In 1946 he took over, in addition, the Chair of Organic Chemistry and he held both these appointments until 1950, when a new Director of the Pharmaceutical Institute was appointed.

Between the years 1948-1952 he supervised the building and equipment of a new Institute of Organic Chemistry, which was ready for occupation in 1952, Reichstein becoming its Director in 1960. He now lives in Basel.

In 1933 Reichstein succeeded, independently of Sir Norman Haworth and his collaborators in Birmingham, in synthesizing vitamin C (ascorbic acid). Otherwise he has worked on the glycosides of plants, and during the years 1953-1954 he worked in collaboration with S. A. S. Simpson and J. F. Tait (London), with A. Wettstein and R. Neher (Ciba Ltd., Basel), and M. Tausk (N.V. Organon, Oss, The Netherlands), and isolated and explained the constitution of aldosterone, a hormone of the adrenal cortex, which until then had not been isolated. Reichstein also collaborated with E. C. Kendall and P. S. Hench in their work on the hormones of the adrenal cortex which culminated in the isolation of cortisone and the discovery of its therapeutic value in the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. For this work, Reichstein, Kendall, and Hench were jointly awarded the Nobel Prize for Physiology or Medicine in 1950.

In 1947 he received the Honorary Doctorate of the Sorbonne, Paris, and in 1952 he was elected a Foreign Member of the Royal Society, London.

Reichstein married Henriette Louise Quarles van Ufford, of Dutch nobility, in 1927. They have one daughter.

Tadeus Reichstein died on August 1, 1996.

It appears to me that if one wants to make progress in mathematics, one should study the masters and not the pupils. - Niels Henrik Abel.

Nothing is better than reading and gaining more and more knowledge - Stephen William Hawking.

Offline

#637 2019-11-27 00:51:03

- Jai Ganesh

- Administrator

- Registered: 2005-06-28

- Posts: 51,610

Re: crème de la crème

603) Lars Fredrik Nilson

Lars Fredrik Nilson (27 May 1840 – 14 May 1899) was a Swedish chemist who discovered scandium in 1879.

Nilson was born in Skönberga parish in Östergötland, Sweden. His father, Nikolaus, was a farmer. The family moved to Gotland when Lars Fredrik was young. After graduating from school, Lars Fredrik enrolled at Uppsala University, and there he studied the natural sciences. His talent for chemistry drew attention from chemistry professor Lars Fredrik Svanberg, who was a former student of Jöns Jakob Berzelius.

In 1874 Nilson became associate professor of chemistry, and from then on he could devote more time to research. While working on rare earths, in 1879 he discovered scandium. During this time he also studied the gas density of metals which made it possible to determine the valence of various metals.

In 1882 he became director of the chemistry research department of the Royal Swedish Academy of Agriculture and Forestry. His research partially took a new direction from then on. He conducted studies on cow milk and various fodder plants.

Nilson was a member of several academies and got several awards, including the Order of the Polar Star.

It appears to me that if one wants to make progress in mathematics, one should study the masters and not the pupils. - Niels Henrik Abel.

Nothing is better than reading and gaining more and more knowledge - Stephen William Hawking.

Offline

#638 2019-11-29 00:14:45

- Jai Ganesh

- Administrator

- Registered: 2005-06-28

- Posts: 51,610

Re: crème de la crème

604) Max Müller

Max Müller, in full Friedrich Max Müller, (born Dec. 6, 1823, Dessau, duchy of Anhalt [Germany]—died Oct. 28, 1900, Oxford, Eng.), German scholar of comparative language, religion, and mythology. Müller’s special areas of interest were Sanskrit philology and the religions of India.

Life And Chief Works

The son of Wilhelm Müller, a noted poet, Max Müller was educated in Sanskrit, the classical language of India, and other languages in Leipzig, Berlin, and Paris. He moved to England in 1846 and settled in Oxford in 1848, where he became deputy professor of modern languages in 1850. He was appointed professor of comparative philology in 1868 and retired in 1875.

Müller was instrumental in editing and translating into English some of the most ancient and revered religious and philosophical texts of Asia. Especially noteworthy are his edition of the great collection of Sanskrit hymns the Rigveda, Rig-Veda-samhitâ: The Sacred Hymns of the Bráhmans (6 vol., 1849–74); his work as editor of the 51-volume series of translations The Sacred Books of the East; and his initial editing of the series Sacred Books of the Buddhists. In addition, Müller was an important early proponent of a discipline that he called the “science of religion”; indeed, some credit him with founding that field. His most important writings on the subject include Essays on the Science of Religion (1869), vol. 1 of Chips from a German Workshop; Introduction to the Science of Religion (1873); and Lectures on the Origin and Growth of Religion (1878).

Ideas On Religion

Müller’s views on religion were shaped by German idealism and the comparative study of language. From the former he derived the conviction that at heart religion is a consciousness of the Infinite; from the latter he formed the belief that religion could only be understood through comparison. As he famously put it, “He who knows one, knows none.”

Like many of his contemporaries, Müller believed that genuine understanding of various aspects of life, including religion, required knowledge of their origins. Accordingly, he expected the science of religion to determine “how religion is possible; how human beings, such as we are, come to have any religion at all; what religion is, and how it came to be what it is.” In pursuing this aim he rejected any reliance on divine revelation—a move more unusual then than now—and sought to limit himself to sense perception and reason, two universally accepted sources of knowledge.

As a philologist, Müller was critical of contemporaries who sought to identify the origins of religion through ethnography. His critique of the then-prevalent theory of fetishism (belief in the magical and protective powers of material objects) is remarkable both for its recognition of Africa’s linguistic and cultural history and diversity and for its identification of the ways in which European Christians constructed images of non-Christians and their religions. Instead of using the prevailing ethnographic approach, Müller pursued the science of religion by studying words and texts. He acknowledged that religion had developed differently in different linguistic spheres and that his training limited him to a consideration of Aryan peoples—that is, speakers of Indo-European languages. Nevertheless, he was convinced that the Rigveda provided unparalleled access to the process by which religion arose.

Müller’s account of that process was largely lexicographical. He began with words and their meanings and sought to show how the idea of gods eventually emerged from them. In his view, human beings first encountered the Infinite when they perceived and named objects that were intangible, such as the Sun, Moon, and stars, or semitangible, such as mountains, rivers, seas, and trees.

It was to such objects that the hymns of the Rigveda were addressed. These hymns were neither polytheistic nor monotheistic but henotheistic (involving worship of one god without denying the existence of other gods): they addressed one object at a time, but they never claimed that it was the only true God. In fact, Müller claimed that, although these natural phenomena provided genuine intimations of the Infinite, they were not originally regarded as gods. If they were called deva (“divine”), a Sanskrit word related to Latin deus (“god”), it was only because they shared the quality of brightness; Müller was especially fond of interpreting myths in terms of solar phenomena. Eventually, however, the objects that shared this and similar qualities were grouped together into classes, conceived of anthropomorphically, and made the subjects of mythology. In terms frequently associated with Müller, the numina (Latin: “deities”) were at first nomina (Latin: “names”); mythology was a kind of disease of language.

Legacy

Even during Müller’s lifetime his ideas were strongly contested by scholars of religions. They found his reliance upon the Rigveda in studying the origin of religions unwarranted and his naturalizing interpretations of mythology strained. A contemporary theologian and Orientalist, R.F. Littledale, suggested that Müller, who had risen in the east (Germany) and come to the west (England) to bring illumination, was himself a solar myth. Nevertheless, Müller’s enthusiasm for the study of religions was undiminished. “The Science of Religion,” he wrote, “may be the last of the sciences which man is destined to elaborate; but when it is elaborated, it will change the aspect of the world” (Chips, xix). This enthusiasm helped to stimulate the scholarship that made Müller’s own ideas obsolete.

It appears to me that if one wants to make progress in mathematics, one should study the masters and not the pupils. - Niels Henrik Abel.

Nothing is better than reading and gaining more and more knowledge - Stephen William Hawking.

Offline

#639 2019-12-01 00:09:02

- Jai Ganesh

- Administrator

- Registered: 2005-06-28

- Posts: 51,610

Re: crème de la crème

605) Elmer Ambrose Sperry

Elmer Ambrose Sperry, (baptized Oct. 12, 1860, Cortland, N.Y., U.S.—died June 16, 1930, Brooklyn, N.Y.), versatile American inventor and industrialist, best known for his gyroscopic compasses and stabilizers.

As a boy, Sperry developed a keen interest in machinery and electricity. At the age of 19 he persuaded a Cortland manufacturer to finance him in developing an improved dynamo as well as an arc lamp. The next year (1880) he went to Chicago and opened a factory, the Sperry Electric Company, to make dynamos and arc lamps. He invented the electric rotary and chain undercutting machines, and, to manufacture them, he established the Sperry Electric Mining Machine Company (1888).

Two years later, he turned his attention to transportation. First, he designed an electrical industrial locomotive and motor transmission machinery for streetcars, founding the Sperry Electric Railway Company in Cleveland (later sold to General Electric Company). From 1894 he made electric automobiles powered by his patented storage battery.

After 1900 he established an electrochemical research laboratory with C.P. Townsend at Washington, D.C. There they invented the chlorine detinning process—for salvaging tin from old cans and scrap—and processes for producing white lead from impure lead and caustic soda from salt. Around this time he also founded the Chicago Fuse Wire Company to manufacture electric fuse wire by machines he had invented. In the meantime, he had not forsaken his old interest in lighting; by 1918 he was producing a high-intensity arc searchlight six times brighter than any earlier light.

Sperry’s greatest inventions sprang from what for decades had been a toy—the gyroscope, which, once properly aligned, always points to true north. The German inventor H. Anschütz-Kaempfe developed the first workable gyrocompass in 1908; Sperry’s version was first installed on the U.S. battleship Delaware in 1911. Sperry set up his Sperry Gyroscope Company in Brooklyn in 1910. He extended the gyro principle to guidance of torpedoes, to gyropilots for the steering of ships and for stabilizing airplanes, and finally to a ship stabilizer.

The Sperry Corporation (now part of Unisys Corporation) manufactured computers, precision instruments and controls, farm machinery, and electric and hydraulic equipment and was a direct descendant of his gyroscope firm. In his lifetime, Sperry founded eight manufacturing companies and took out more than 400 patents.

(Gyrocompass, navigational instrument which makes use of a continuously driven gyroscope to accurately seek the direction of true (geographic) north. It operates by seeking an equilibrium direction under the combined effects of the force of gravity and the daily rotation of Earth. As such, it is immune to magnetic interferences such as those caused by ore deposits, steel structures, or electric circuits. These properties make the gyrocompass a prime navigational device in ships and submarines. It has found extensive use on ore ships on the Great Lakes, as the azimuth reference for gun and torpedo control on warships, and as a reliable compass for navigation of any ship. It is not suitable as an aircraft compass because the speed of several hundred knots associated with such vehicles seriously affects the north-seeking properties of the instrument.)

It appears to me that if one wants to make progress in mathematics, one should study the masters and not the pupils. - Niels Henrik Abel.

Nothing is better than reading and gaining more and more knowledge - Stephen William Hawking.

Offline

#640 2019-12-03 00:46:37

- Jai Ganesh

- Administrator

- Registered: 2005-06-28

- Posts: 51,610

Re: crème de la crème

606) Wilhelm Normann

Wilhelm Normann (16 January 1870, in Petershagen – 1 May 1939, in Chemnitz) (sometimes also spelled Norman) was a German chemist who introduced the hydrogenation of fats in 1901, creating what later became known as trans fats. This invention, protected by German patent 141,029 in 1902, had a profound influence on the production of margarine and vegetable shortening.

Early life and education

His father, Julius Normann, was the principal of the elementary school and Selekta in Petershagen. His mother was Luise Normann, née Siveke.

Normann attended primary school from 31 March 1877. At Easter of his sixth grade he moved to the Friedrichs Gymnasium in Herford. After his father applied for a teacher's job at the municipal secondary school in Kreuznach, Wilhelm changed to the Royal Secondary School in Kreuznach. He passed his examinations and left school at the age of 18.

Career

Normann began work at the Herford machine fat and oil factory Leprince & Siveke in 1888. The founder of that company was his uncle, Wilhelm Siveke. After running a branch of the company in Hamburg for two years, he started studying chemistry at the laboratory of Professor Carl Remigius Fresenius in Wiesbaden. From April 1892 Normann continued his studies at the department of oil analytics at the Berlin Institute of Technology under the supervision of Professor D. Holde. From 1895 to 1900 he studied chemistry under supervision of Prof. Claus and Prof. Willgerod and geology under supervision of Prof. Steinmann at the Albert Ludwigs University of Freiburg. There he received his doctorate in 1900 with a work about Beiträge zur Kenntnis der Reaktion zwischen unterchlorigsauren Salzen und primären aromatischen Aminen ("Contributions to the knowledge of the reactions of hypochlorite salts and primary aromatic amines"). In 1901 Normann was appointed as correspondent of the Federal Geological Institute.

Primary work

From 1901 to 1909 he was head of the laboratory at Leprince & Siveke, where conducted investigations of the properties of fats and oils.

In 1901 Normann heard about Paul Sabatier publishing an article, in which Sabatier stated that only with vaporizable organic compounds it is possible to bind catalytic hydrogen to fluid tar oils. Normann investigated and disproved Sabatier's assertion. He was able to transform liquid oleic acid into solid stearic acid by the use of catalytic hydrogenation with dispersed nickel. This was the precursor of saturated fat hardening.

On 27 February 1901 Normann invented what he called fat hardening, which was the process of producing saturated fats. On 14 August 1902 the German Imperial patent office granted patent 141,029 to the Leprince & Siveke Company, and on 21 January 1903 Normann was granted the British patent, GB 190301515 "Process for Converting Unsaturated Fatty Acids or their Glycerides into Saturated Compounds".

During the years 1905 to 1910 Normann built a fat hardening facility in the Herford company. In 1908 the patent was bought by Joseph Crosfield & Sons Limited of Warrington, England. From the autumn of 1909 hardened fat was being successfully produced in what in a large scale plant in Warrington. The initial year's production was nearly 3,000 tonnes (3,000 long tons; 3,300 short tons). When Lever Brothers produced a rival process Crosfield took them to court over patent infringement, which Crosfield lost.

From 1911 to 1922, Normann was scientific director of Ölwerke Germania (Germania Oil Factory) in Emmerich am Rhein, which was established by the Dutch Jürgens company.

From 1917, Normann built a fat hardening factory in Antwerp for the margarine company SAPA Societe anonyme des grasses, huiles et produits africaines, which operated in India. He served as technical director by order of the Belgian Colonial Society.

On 25 April 1920 he filed for German patent 407180 Verfahren zur Herstellung von gemischten Glyceriden (Procedure for the production of mixed glycerides), which was approved on 9 December 1924.

On 26 June 1920 the Firma Oelwerke Germania and Dr Wilhelm Normann filed for German patent 417215, Verfahren zur Umesterung von Fettsaurestern. (Procedure for the transesterification of fatty esters), which was approved on 27 September 1925.

From 1924 to 1927 Normann was a consultant for fat hardening facilities for foreign companies.

On 30 October 1926 Normann and the Volkmar Haenig & Comp, Metallochemische Werk Rodlebe company filed for German patent 564894, for Elektrisch beheizter Etagenroester (Electrically heated esters), approved 24 November 1932.

On 14 May 1929 he applied for German patent 582266, Verfahren zur Darstellung von Estern (Procedure for the representation of esters), which was approved on 11 August 1933.

Personal life

Normann married Martha Uflerbäumer of Herford on 12 September 1916.

On 1 January 1939 Normann retired, and he died on 1 May 1939 after an illness in the Küchwald Hospital in Chemnitz. He was entombed on 5 May 1939 in the family grave at the old cemetery on Hermannstrasse in Herford.

Awards

• 8 June 1922: Award of the Liebig Medal by the German Chemical Society.

• February 1939: awarded an honorary doctorate of natural sciences by the Faculty of Natural Sciences and the senate of the University of Münster in Westfalen.

• 1939: awarded honorary membership in the Deutsche Gesellschaft für Fettforschung (DGF; German Society for Fat Research), today Deutsche Gesellschaft für Fettwissenschaft (German Society for Fat Science), Münster.

In commemoration of the inventor of fat hardening the DGF donated the Wilhelm Normann Medal on 15 May 1940. Since 1940 it has been irregularly awarded.

The Wilhelm-Normann-Berufskolleg (Wilhelm Normann Professional College) in Herford was named after Normann.

It appears to me that if one wants to make progress in mathematics, one should study the masters and not the pupils. - Niels Henrik Abel.

Nothing is better than reading and gaining more and more knowledge - Stephen William Hawking.

Offline

#641 2019-12-05 00:08:10

- Jai Ganesh

- Administrator

- Registered: 2005-06-28

- Posts: 51,610

Re: crème de la crème

607) Marcel Roland de Quervain

Marcel Roland de Quervain, (born May 17, 1915, Zürich, Switzerland—died February 2007), Swiss glaciologist known for his fundamental work on the metamorphism and physical properties of snow.

Quervain was assistant director (1943–50) and director (from 1950 until his retirement in 1980) of the Swiss Snow and Avalanche Research Institute. He offered major contributions in the understanding of snow structure and the development of avalanche warning systems. In 1959 he was a member of the International Glaciological Expedition to Greenland, where he studied the stratification and structure of the ice sheet. He served as vice president of the International Association for Scientific Hydrology from 1968 to 1971, and in 1975 Quervain was elected president of the International Glaciological Society.

It appears to me that if one wants to make progress in mathematics, one should study the masters and not the pupils. - Niels Henrik Abel.

Nothing is better than reading and gaining more and more knowledge - Stephen William Hawking.

Offline

#642 2019-12-05 01:13:13

- Jai Ganesh

- Administrator

- Registered: 2005-06-28

- Posts: 51,610

Re: crème de la crème

608) Kary Mullis

Kary Mullis, in full Kary Banks Mullis, (born December 28, 1944, Lenoir, North Carolina, U.S.—died August 7, 2019, Newport Beach, California), American biochemist, cowinner of the 1993 Nobel Prize for Chemistry for his invention of the polymerase chain reaction (PCR), a simple technique that allows a specific stretch of DNA to be copied billions of times in a few hours.

After receiving a doctorate in biochemistry from the University of California, Berkeley, in 1973, Mullis held research posts at various universities. In 1979 he joined Cetus Corp., a California biotechnology firm, where he carried out his prizewinning research. From 1986 to 1988 he was director of molecular biology for Xytronyx, Inc., in San Diego, California; thereafter he worked as a freelance consultant.

Mullis developed PCR in 1983. Earlier methods for obtaining a specific sequence of DNA in quantities sufficient for study were difficult, time-consuming, and expensive. PCR uses four ingredients: the double-stranded DNA segment to be copied, called the template DNA; two oligonucleotide primers (short segments of single-stranded DNA, each of which is complementary to a short sequence on one of the strands of the template DNA); nucleotides, the chemical building blocks that make up DNA; and a polymerase enzyme that copies the template DNA by joining the free nucleotides in the correct order. These ingredients are heated, causing the template DNA to separate into two strands. The mixture is cooled, allowing the primers to attach themselves to the complementary sites on the template strands. The polymerase is then able to begin copying the template strands by adding nucleotides onto the end of the primers, producing two molecules of double-stranded DNA. Repeating this cycle increases the amount of DNA exponentially: some 30 cycles, each lasting only a few minutes, will produce more than a billion copies of the original DNA sequence.