Math Is Fun Forum

You are not logged in.

- Topics: Active | Unanswered

#851 2021-01-27 00:09:22

- Jai Ganesh

- Administrator

- Registered: 2005-06-28

- Posts: 52,766

Re: crème de la crème

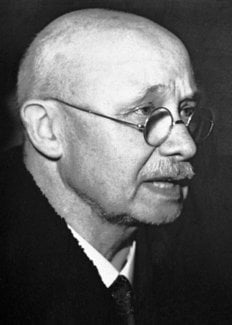

817) Otto Diels

Otto Paul Hermann Diels was born in Hamburg, Germany, on January 23, 1876. When he was two years of age the family moved to Berlin, where his father was appointed to a professorship. His early education, from 1882 to 1895, was at the Joachimsthalsches Gymnasium, Berlin. In 1895 he went to Berlin University where he studied chemistry, together with other science subjects, under Emil Fischer, graduating in 1899. He was at once appointed assistant at the Institute of Chemistry at Berlin University, becoming a lecturer in 1904. Promotion to Professor followed in 1906, and he was appointed Head of Department in 1913. He became Professor at the University of Berlin in 1915 but, the following year, moved to the University of Kiel as Professor and Director of the Institute of Chemistry. There he remained until his retirement in 1945.

His earliest research was in the field of inorganic chemistry, where he was the discoverer of an oxide of carbon having some unusual properties – carbon suboxide. His subsequent work was in the domain of organic chemistry. He was responsible for introducing the use of selenium as a specific reagent for the dehydrogenation of hydroaromatic compounds (1927). This proved to be a very useful tool in elucidating chemical structures in the complicated steroid series, where his name is associated with the hydrocarbon 3′-methyl-1,2-cyclopentenophenanthrene. Diels obtained this skeletal steroid structure by dehydrogenating cholesterol, and other members of the series, with selenium.

His best known work was done in collaboration with Kurt Alder on the chemical reaction which bears their joint names (1928). This, sometimes known also as the diene synthesis, consists in the reaction of a diene with a second component which has carbonyl or carboxyl groups adjoining an ethylenic bond, to give unsaturated cyclic compounds. As the two reactants can be varied widely within the scope of this definition, a very large range of new compounds can be prepared. The reaction takes place without the need for forcing conditions and, by its use, many complicated natural products, and modifications thereof, may be synthesized.

Diels was the author of the ‘Einführung in die organische Chemie’ (1907), which went through fifteen editions. He had many papers published, mostly in German scientific periodicals such as ‘Liebigs Annalen der Chemie’.

One of his earliest awards was in 1904, when he was awarded a Gold Medal at the St. Louis (USA) International Exhibition. He won the Adolf v. Baeyer Medallion in 1930 and the Grosskreuz des Verdienstordens der Bundesrepublik Deutschland in 1952. He held the honorary degree of Doctor of Medicine from the University of Kiel and was a member of the Academies of Halle, Munich, and Göttingen.

Diels married, in 1909, Paula Geyer. They had three sons and two daughters; two of their sons were killed in action during World War II. He was interested in reading, music, and travel for his recreation, and, in his younger days, he had been fond of mountaineering. He died on March 7, 1954.

It appears to me that if one wants to make progress in mathematics, one should study the masters and not the pupils. - Niels Henrik Abel.

Nothing is better than reading and gaining more and more knowledge - Stephen William Hawking.

Offline

#852 2021-01-29 00:22:55

- Jai Ganesh

- Administrator

- Registered: 2005-06-28

- Posts: 52,766

Re: crème de la crème

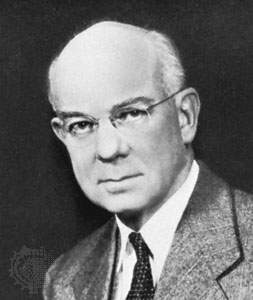

818) Kurt Alder

Kurt Alder was born in Königshütte, Upper Silesia, on the 10th of July 1902. His childhood and school years were spent in these industrial surroundings, but after the end of the First World War he was forced to leave his home, due to political circumstances.

He started reading chemistry at Berlin University in 1922, and later continued these studies at Kiel, where he obtained his degree of Ph.D. in 1926. The thesis for the doctorate, on which Alder worked under O. Diels, was entitled: Über die Ursachen der Azoester-reaktion (On the causes of the azoester reaction).

In 1930 Alder was appointed reader for chemistry by the Faculty of Philosophy at Kiel University; promotion to lecturer followed in 1934. Alder left Kiel in 1936 to take up the appointment as head of department in the science laboratories of the I. G. Farben-Industrie, at their works in Leverkusen, where he worked on the preparation and constitution of synthetic rubber (“Buna”). By this work some of his earlier interests were reawakened and stimulated.

In 1940 Alder was appointed to the Chair for Experimental Chemistry and Chemical Technology at Cologne University and also became Principal of the Institute of Chemistry. He received invitations from Berlin University in 1944 and from the University of Marburg in 1950, but declined both.

As early as 1927-1928, whilst at Kiel, Alder had studied problems of systematic organic chemistry in collaboration with his teacher O. Diels, and this lead to their joint discovery of the principle of the diene-synthesis, which they investigated and determined in all its aspects. At the same time Alder also worked in collaboration with younger colleagues on extensive stereochemical investigations, prompted by selection phenomena during organic chemical reactions, particularly in unsaturated systems. A series of other problems, such as the behaviour of double bonds in stressed carbon rings and the phenomena of intermolecular rearrangements, were investigated.

Although conditions in Cologne during the 1940’s were not favourable for scientific research, Alder was nevertheless able to continue his original work systematically and even discover relationships which were decisive for future developments. These are characterized by the transition from pure additive processes, of which the diene-synthesis is the most important, to processes of substitution. The purpose of these investigations was the analysis and the elimination of the dualism existing between addition and substitution. These studies covered a wide field and include also the reaction of molecular oxygen on unsaturated substrates.

Kurt Alder’s investigations have been described in about 150 papers, which were published mainly in Justus Liebig’s Annalen der Chemie, in the Berichte der Deutschen Chemischen Gesellschaft and in Angewandte Chemie.

In recognition of his work, Alder received the Emil Fischer Memorial Medal from the Association of German Chemists, in 1938. In the same year he became a member of the Kaiserlich Leopold.-Karol.-Deutsche Akademie der Naturforscher (Imperial Leopold.-Karol.-German Academy of Natural Philosophers) in Halle. The Medical Faculty of the University of Cologne conferred the honorary degree of M.D. on Alder in 1950, and in 1954 he received the honorary doctorate of the University of Salamanca.

Kurt Alder died on June 20, 1958.

It appears to me that if one wants to make progress in mathematics, one should study the masters and not the pupils. - Niels Henrik Abel.

Nothing is better than reading and gaining more and more knowledge - Stephen William Hawking.

Offline

#853 2021-01-31 00:27:55

- Jai Ganesh

- Administrator

- Registered: 2005-06-28

- Posts: 52,766

Re: crème de la crème

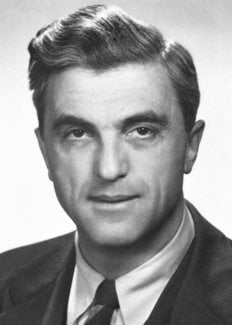

819) Philip S. Hench

Philip Showalter Hench was born in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania on February 28, 1896, the son of Jacob Bixler Hench and Clara Showalter. After attending local schools he entered Lafayette College, Easton, Penn., where he graduated Bachelor of Arts in 1916. He enlisted in the Medical Corps of the United States Army in 1917 but was transferred to the reserve corps to finish his medical training. In 1920 he received his doctorate in medicine from the University of Pittsburgh. After a year as an interne at Saint Francis Hospital, Pittsburgh, he became a Fellow of the Mayo Foundation, the graduate school of the University of Minnesota’s Department of Medicine. His association with the Mayo Clinic began in 1923 when he became first an assistant, then, three years later, Head of its Department of Rheumatic Diseases. Between 1928 and 1929, Dr. Hench studied abroad, at Freiburg University and at the von Müller Clinic, Munich. He was appointed an instructor in the Mayo Foundation in 1928, Assistant Professor 1932, Associate Professor 1935 and, in 1947, Professor of Medicine, a position which he still holds.

In 1942 Dr. Hench entered military service as a lieutenant-colonel in the Medical Corps, becoming Chief of the Medical Service and Director of the Army’s Rheumatism Centre at the Army and Navy General Hospital. Leaving the army with the rank of colonel, in 1946, he became expert consultant to the Army Surgeon General, which position is still held by him.

At the Mayo Clinic he specialized in arthritic disease. In the course of his work he observed the favourable effects of jaundice on arthritic patients, causing a remission of pain. Other bodily changes, for example pregnancy, produced the same effect. These and other observations led him gradually to the conclusion that the pain-alleviating substance was a steroid.

In the period 1930-1938, Dr. E. C. Kendall had isolated several steroids from the adrenal gland cortex. After several years of collaboration with Dr. Kendall, it was decided to try the effect of one of these substances, Compound E (later named cortisone), on arthritic patients. Delay in implementing this decision was caused by Dr. Hench’s military service in World War II and by the costly and complicated isolation of the substance. In 1948-1949, cortisone was successfully tested on arthritic patients. Hench also treated patients with ACTH, a hormone produced by the pituitary gland which stimulates the adrenal gland.

Dr. Hench is the author of several papers in the field of rheumatology, contributed mainly to ‘Hygeia and the Annals of Rheumatic Diseases’. His many awards include the Heberden Medal (London), the 1949 Lasker Award, presented by the American Public Health Association, the Passano Foundation Award and the Criss Award (1951). He has received honorary doctorates in science from Lafayette College, Washington and Jefferson College, Western Reserve University, the National University of Ireland and the University of Pittsburgh. He holds the degree of master of science from the University of Minnesota.

A Fellow of the American Medical Association and of the American College of Physicians, he is one of the leaders in American rheumatology. He is a founder member of the American Rheumatism Association (President 1940-1941), and holds office in many rheumatism organizations. He holds honorary membership of the Royal Society of Medicine (London) and of rheumatism societies in Argentina, Brazil, Canada, Denmark and Spain.

In 1927, Dr. Hench married Mary Genevieve Kahler, daughter of John Henry Kahler. They have two sons and two daughters. He is interested in music, photography and tennis, and is an authority on medical history.

Philip S. Hench died on March 30, 1965.

It appears to me that if one wants to make progress in mathematics, one should study the masters and not the pupils. - Niels Henrik Abel.

Nothing is better than reading and gaining more and more knowledge - Stephen William Hawking.

Offline

#854 2021-02-02 00:03:07

- Jai Ganesh

- Administrator

- Registered: 2005-06-28

- Posts: 52,766

Re: crème de la crème

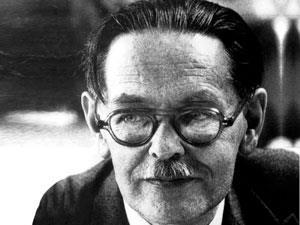

820) Edward C. Kendall

Edward Calvin Kendall was born on March 8, 1886, at South Norwalk, Connecticut, U.S.A. He was educated at Columbia University, where he obtained the degrees of Bachelor of Science in 1908 and Master of Science, specializing in Chemistry, in 1909. From 1909 until 1910 he was Goldschmidt Fellow of this University, and in 1910 he obtained his Ph.D. in Chemistry.

From 1910 until 1911 he was research chemist for Parke, Davis and Co., at Detroit, Michigan, U.S.A. Here he did research on the thyroid gland, and from 1911 until 1914 he continued this work at St. Luke’s Hospital, New York.

In 1914 he was appointed Head of the Biochemistry Section in the Graduate School of the Mayo Foundation, Rochester which is affiliated with the University of Minnesota, and in 1915 he was appointed Director of the Division of Biochemistry there and subsequently Professor of Physiological Chemistry. On April 1, 1951, Kendall reached the age of retirement from the Mayo Foundation and he accepted the position of Visiting Professor in the Department of Biochemistry at Princeton University, a position, which at the time of writing, he still holds.

Kendall’s name will always be associated with his isolation of thyroxine, the active principle of the thyroid gland, but he is also known for his crystallization of glutathione, the chemical nature of which he established, and also for his work on the oxidation systems in animals. Perhaps his greatest achievement, however, was his work on the hormones of the cortex of the adrenal glands. Chemical investigation of the adrenal cortex was carried out simultaneously but independently by Kendall and T. Reichstein with their associates. The former at the Mayo Foundation, Rochester, Minnesota; the latter at Zurich, Switzerland.

After many years the hormones of the adrenal cortex were isolated, identified, and prepared by synthetic methods in small amounts. Subsequently, they were made commercially on a scale sufficiently large to permit a study of their physiological effects. Previous to this, Dr. Philip Hench, also at the Mayo Foundation, had observed that patients who had rheumatoid arthritis were sometimes relieved if they developed jaundice. In women, rheumatoid arthritis was sometimes relieved during pregnancy. When one of the hormones of the adrenal cortex was given to patients by Dr. Hench, the anti-inflammatory effect of the compound, cortisone, was discovered. It was then found that many other diseases of an inflammatory nature were relieved by cortisone. Although it was found later that cortisone, like insulin, acts only so long as it is given to the patient, and that it does not cure the disease, the discovery of the activity of cortisone was a great step forward. It has led to our modern knowledge of the hormones of the adrenal cortex and their uses in medicine. For their work, Kendall, Hench, and Reichstein jointly were given the Nobel Prize for Physiology and Medicine for 1950. Since his retirement to Princeton University, Kendall has continued his studies of the chemistry of the adrenal cortex.

Kendall received many awards and other honours, some of these (Lasker Award of the American Public Health Service, Passano Award of the Passano Foundation in San Francisco, and Page One Award of the Newspaper Guild of New York) jointly with Dr. Hench. On December 1915, he married Rebecca Kennedy; they have two children.

Edward C. Kendall died on May 4, 1972.

It appears to me that if one wants to make progress in mathematics, one should study the masters and not the pupils. - Niels Henrik Abel.

Nothing is better than reading and gaining more and more knowledge - Stephen William Hawking.

Offline

#855 2021-02-04 00:15:18

- Jai Ganesh

- Administrator

- Registered: 2005-06-28

- Posts: 52,766

Re: crème de la crème

821) Edwin Mattison McMillan

Edwin Mattison McMillan, (born September 18, 1907, Redondo Beach, California, U.S.—died September 7, 1991, El Cerrito, California), American nuclear physicist who shared the Nobel Prize for Chemistry in 1951 with Glenn T. Seaborg for his discovery of element 93, neptunium, the first element heavier than uranium, thus called a transuranium element.

McMillan was educated at the California Institute of Technology and at Princeton University, where he earned a Ph.D. in 1932. He then joined the faculty of the University of California, Berkeley, and became a full professor in 1946 and director of the Lawrence Radiation Laboratory in 1958. He retired in 1973.

While studying nuclear fission, McMillan discovered neptunium, a decay product of uranium-239. In 1940, in collaboration with Philip H. Abelson, he isolated the new element and obtained final proof of his discovery. Neptunium was the first of a host of transuranium elements that provide important nuclear fuels and contributed greatly to the knowledge of chemistry and nuclear theory. During World War II McMillan also did research on radar and sonar and worked on the first atomic bomb. He served as a member of the General Advisory Committee to the U.S. Atomic Energy Commission from 1954 to 1958.

McMillan also made a major advance in the development of Ernest Lawrence’s cyclotron, which in the early 1940s had run up against its theoretical limit. Accelerated in an ever-widening spiral by synchronized electrical pulses, atomic particles in a cyclotron are unable to attain a velocity beyond a certain point, as a relativistic mass increase tends to put them out of step with the pulses. In 1945, independently of the Russian physicist Vladimir I. Veksler, McMillan found a way of maintaining synchronization for indefinite speeds. He coined the name synchrocyclotron for accelerators using this principle. McMillan was chairman of the National Academy of Sciences from 1968 to 1971.

It appears to me that if one wants to make progress in mathematics, one should study the masters and not the pupils. - Niels Henrik Abel.

Nothing is better than reading and gaining more and more knowledge - Stephen William Hawking.

Offline

#856 2021-02-06 00:25:31

- Jai Ganesh

- Administrator

- Registered: 2005-06-28

- Posts: 52,766

Re: crème de la crème

822) Tadeus Reichstein

Tadeus Reichstein, (born July 20, 1897, Włocławek, Pol.—died Aug. 1, 1996, Basel, Switz.), Swiss chemist who, with Philip S. Hench and Edward C. Kendall, received the Nobel Prize for Physiology or Medicine in 1950 for his discoveries concerning hormones of the adrenal cortex.

Reichstein was educated in Zürich and held posts in the department of organic chemistry at the Federal Institute of Technology, Zürich, from 1930. From 1946 to 1967 he was professor of organic chemistry at the University of Basel. He received the Nobel Prize for research carried out independently on the steroid hormones produced by the adrenal cortex, the outer layer of the adrenal gland. Reichstein and his colleagues isolated about 29 hormones and determined their structure and chemical composition. One of the hormones they isolated, cortisone, was later discovered to be an anti-inflammatory agent useful in the treatment of arthritis. Reichstein was also involved in developing methods to synthesize the hormones he had discovered, among them cortisone and desoxycorticosterone, which was used for many years to treat Addison’s disease.

Apart from hormone research, Reichstein is also known for his synthesis of vitamin C, a feat achieved about the same time (1933) in England by Sir Walter N. Haworth and coworkers. In the latter part of his career, Reichstein studied plant glycosides, chemicals that can be used in the development of therapeutic drugs. He was awarded the Copley Medal of the British Royal Society in 1968.

It appears to me that if one wants to make progress in mathematics, one should study the masters and not the pupils. - Niels Henrik Abel.

Nothing is better than reading and gaining more and more knowledge - Stephen William Hawking.

Offline

#857 2021-02-08 00:06:52

- Jai Ganesh

- Administrator

- Registered: 2005-06-28

- Posts: 52,766

Re: crème de la crème

823) Max Theiler

Max Theiler, (born January 30, 1899, Pretoria, South Africa—died August 11, 1972, New Haven, Connecticut, U.S.), South African-born American microbiologist who won the 1951 Nobel Prize for Physiology or Medicine for his development of a vaccine against yellow fever.

Theiler received his medical training at St. Thomas’s Hospital, London, and the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, graduating in 1922. In that year he joined the department of tropical medicine at Harvard Medical School, Boston. There he carried out important studies of amebic dysentery and rat-bite fever and began work on yellow fever.

In 1930 Theiler joined the laboratories at the Rockefeller Foundation’s International Health Division in New York City, where he continued his research on infectious diseases, including yellow fever. With the discovery in 1928 that rhesus monkeys were susceptible to the virus responsible for yellow fever, researchers began to develop vaccines against the disease. Theiler discovered that the common mouse is also susceptible to the yellow fever virus, a finding that facilitated the vaccine research. In the late 1930s Theiler developed the first attenuated, or weakened, strain of the virus. Further studies led to the development of the improved 17D strain that became widely used for human immunization against yellow fever.

Theiler was director of the Rockefeller Foundation Virus Laboratories from 1951 to 1963. After retiring from the Rockefeller Foundation in 1964, he became professor of epidemiology and microbiology at Yale University, where he remained until 1967.

It appears to me that if one wants to make progress in mathematics, one should study the masters and not the pupils. - Niels Henrik Abel.

Nothing is better than reading and gaining more and more knowledge - Stephen William Hawking.

Offline

#858 2021-02-10 00:17:55

- Jai Ganesh

- Administrator

- Registered: 2005-06-28

- Posts: 52,766

Re: crème de la crème

824) Felix Bloch

Felix Bloch, (born Oct. 23, 1905, Zürich, Switz.—died Sept. 10, 1983, Zürich), Swiss-born American physicist who shared (with E.M. Purcell) the Nobel Prize for Physics in 1952 for developing the nuclear magnetic resonance method of measuring the magnetic field of atomic nuclei.

Bloch’s doctoral dissertation (University of Leipzig, 1928) promulgated a quantum theory of solids that provided the basis for understanding electrical conduction. Bloch taught at the University of Leipzig until 1933; when Adolf Hitler came to power he emigrated to the United States and was naturalized in 1939. After joining the faculty of Stanford University, Palo Alto, Calif., in 1934, he proposed a method for splitting a beam of neutrons into two components that corresponded to the two possible orientations of a neutron in a magnetic field. In 1939, using this method, he and Luis Alvarez (winner of the Nobel Prize for Physics in 1968) measured the magnetic moment of the neutron (a property of its magnetic field). Bloch worked on atomic energy at Los Alamos, N.M., and radar countermeasures at Harvard University during World War II.

Bloch returned to Stanford in 1945 to develop, with physicists W.W. Hansen and M.E. Packard, the principle of nuclear magnetic resonance, which helped establish the relationship between nuclear magnetic fields and the crystalline and magnetic properties of various materials. It later became useful in determining the composition and structure of molecules. Nuclear magnetic resonance techniques have become increasingly important in diagnostic medicine.

Bloch was the first director general of the European Organization for Nuclear Research (1954–55; CERN).

It appears to me that if one wants to make progress in mathematics, one should study the masters and not the pupils. - Niels Henrik Abel.

Nothing is better than reading and gaining more and more knowledge - Stephen William Hawking.

Offline

#859 2021-02-12 00:07:52

- Jai Ganesh

- Administrator

- Registered: 2005-06-28

- Posts: 52,766

Re: crème de la crème

825) E. M. Purcell

Edward Mills Purcell was born in Taylorville, Illinois, U.S.A., on August 30, 1912. His parents, Edward A. Purcell and Mary Elizabeth Mills, were both natives of Illinois. He was educated in the public schools in Taylorville and in Mattoon, Illinois, and in 1929 entered Purdue University in Indiana. He graduated from Purdue in electrical engineering in 1933.

His interest had already turned to physics, and through the kindness of Professor K. Lark-Horovitz he was enabled, while an undergraduate, to take part in experimental research in electron diffraction. As an Exchange Student of the Institute of International Education, he spent one year at the Technische Hochschule, Karlsruhe, Germany, where he studied under Professor W. Weizel. He returned to the United States in 1934 to enter Harvard University, where he received the Ph.D. degree in 1938. After serving two years as instructor in physics at Harvard, he joined the Radiation Laboratory, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, which was organized in 1940 for military research and development of microwave radar. He became Head of the Fundamental Developments Group in the Radiation Laboratory, which was concerned with the exploration of new frequency bands and the development of new microwave techniques. This experience turned out to be very valuable. Perhaps equally influential in his subsequent scientific work was the association at this time with a number of physicists, among them I.I. Rabi, with a continuing interest in the study of molecular and nuclear properties by radio methods.

The discovery of nuclear magnetic resonance absorption was made just after the end of the War, and at about that time Purcell returned to Harvard as Associate Professor of Physics. He became Professor of Physics in 1949; his present title is Gerhard Gade University Professor. He has continued to work in the field of nuclear magnetism, with particular interest in relaxation phenomena, related problems of molecular structure, measurement of atomic constants, and nuclear magnetic behaviour at low temperatures. He has made some contribution to the subject of radioastronomy.

He is a Fellow of the American Physical Society, a member of the National Academy of Sciences, of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, and of the President’s Science Advisory Committee under President Eisenhower from 1957-1960 and under President Kennedy as from 1960.

In 1937, Purcell married Beth C. Busser. They have two sons, Dennis and Frank.

E.M. Purcell died on March 7, 1997.

It appears to me that if one wants to make progress in mathematics, one should study the masters and not the pupils. - Niels Henrik Abel.

Nothing is better than reading and gaining more and more knowledge - Stephen William Hawking.

Offline

#860 2021-02-14 00:04:38

- Jai Ganesh

- Administrator

- Registered: 2005-06-28

- Posts: 52,766

Re: crème de la crème

826) A.J.P. Martin

A.J.P. Martin, in full Archer John Porter Martin, (born March 1, 1910, London, England —died July 28, 2002, Llangarron, Herefordshire), British biochemist who was awarded (with R.L.M. Synge) the Nobel Prize for Chemistry in 1952 for development of paper partition chromatography, a quick and economical analytical technique permitting extensive advances in chemical, medical, and biological research.

Martin obtained a Ph.D. from the University of Cambridge in 1936 and worked as a research chemist for the Wool Industries Research Association in Leeds from 1938 to 1946. He then became head of biochemical research at the Boots Pure Drug Company, Nottingham, and held the post until 1948, when he was appointed to the staff of the British Medical Research Council. From 1959 to 1970 he was director of Abbotsbury Laboratories, Ltd. Martin also taught at the University of Houston in Texas (1974–79).

Martin and Synge invented paper partition chromatography in 1944. Partition chromatography depends on the partition, or distribution, of each component of a mixture between two immiscible liquids. One of the liquids is held stationary by strong adsorption on the surface of a finely divided solid while the other flows through the interstices of the solid particles. Any substance that preferentially dissolves in the mobile liquid is more rapidly transported in the direction of flow than is a substance that has greater affinity for the stationary liquid. In 1953 Martin and A.T. James helped perfect gas chromatography, the separation of chemical vapours by differential absorption on a porous solid.

It appears to me that if one wants to make progress in mathematics, one should study the masters and not the pupils. - Niels Henrik Abel.

Nothing is better than reading and gaining more and more knowledge - Stephen William Hawking.

Offline

#861 2021-02-16 00:07:49

- Jai Ganesh

- Administrator

- Registered: 2005-06-28

- Posts: 52,766

Re: crème de la crème

827) R.L.M. Synge

R.L.M. Synge, in full Richard Laurence Millington Synge, (born Oct. 28, 1914, Liverpool, Eng.—died Aug. 18, 1994, Norwich, Norfolk), British biochemist who in 1952 shared the Nobel Prize for Chemistry with A.J.P. Martin for their development of partition chromatography, notably paper chromatography.

Synge studied at Winchester College, Cambridge, and received his Ph.D. at Trinity College there in 1941. He spent his entire professional career conducting research, initially with Martin under the auspices of the Wool Industries Research Association, Leeds (1941–43). The two men developed partition chromatography, a technique that is used to separate mixtures of closely related chemicals such as amino acids for identification and further study. Synge used paper chromatography to work out the exact structure of the simple protein molecule gramicidin S, which helped to pave the way for the English biochemist Frederick Sanger’s elucidation of the structure of the insulin molecule.

Synge did research at the Lister Institute of Preventive Medicine, London (1943–48), and at the Rowett Research Institute, near Aberdeen, Scot. (1948–67). He became a biochemist at the Food Research Institute, Norwich (1967–76), and was also an honorary professor of biological sciences at the University of East Anglia (1968–84).

It appears to me that if one wants to make progress in mathematics, one should study the masters and not the pupils. - Niels Henrik Abel.

Nothing is better than reading and gaining more and more knowledge - Stephen William Hawking.

Offline

#862 2021-02-18 00:03:21

- Jai Ganesh

- Administrator

- Registered: 2005-06-28

- Posts: 52,766

Re: crème de la crème

828) Selman Abraham Waksman

Selman Abraham Waksman, (born July 22, 1888, Priluka, Ukraine, Russian Empire [now Pryluky, Ukraine]—died August 16, 1973, Hyannis, Massachusetts, U.S.), Ukrainian-born American biochemist who was one of the world’s foremost authorities on soil microbiology. After the discovery of penicillin, he played a major role in initiating a calculated, systematic search for antibiotics among microbes. His screening methods and consequent codiscovery of the antibiotic streptomycin, the first specific agent effective in the treatment of tuberculosis, brought him the 1952 Nobel Prize for Physiology or Medicine.

A naturalized U.S. citizen (1916), Waksman spent most of his career at Rutgers University, New Brunswick, New Jersey, where he served as professor of soil microbiology (1930–40), professor of microbiology and chairman of the department (1940–58), and director of the Rutgers Institute of Microbiology (1949–58). During his extensive study of the actinomycetes (filamentous, bacteria-like microorganisms found in the soil), he extracted from them antibiotics (a term he coined in 1941) valuable for their killing effect not only on gram-positive bacteria, such as the tubercle bacillus (Mycobacterium tuberculosis, which unlike other gram-positive microbes is insensitive to penicillin), but also on gram-negative bacteria, such as the organisms that cause cholera (Vibrio cholerae) and typhoid fever (Salmonella typhi).

In 1940 Waksman, along with his graduate student H. Boyd Woodruff, isolated actinomycin from soil bacteria. Although the substance was effective against strains of gram-negative and gram-positive bacteria, including M. tuberculosis, it was extremely toxic when given to test animals. Four years later Waksman and graduate students Albert Schatz and Elizabeth Bugie published a paper describing their discovery of the relatively nontoxic streptomycin, which they extracted from the actinomycete Streptomyces griseus. They found that the antibiotic exercised repressive influence on tuberculosis. In combination with other chemotherapeutic agents, streptomycin has become a major factor in controlling the disease. Waksman also isolated and developed several other antibiotics, including neomycin, that have been used in treating many infectious diseases of humans, domestic animals, and plants.

Among Waksman’s books are ‘Principles of Soil Microbiology (1927)’, regarded as one of the most exhaustive works on the subject, and ‘My Life with the Microbes (1954)’, an autobiography.

It appears to me that if one wants to make progress in mathematics, one should study the masters and not the pupils. - Niels Henrik Abel.

Nothing is better than reading and gaining more and more knowledge - Stephen William Hawking.

Offline

#863 2021-02-20 00:06:18

- Jai Ganesh

- Administrator

- Registered: 2005-06-28

- Posts: 52,766

Re: crème de la crème

829) Frits Zernike

Frits Zernike, (born July 16, 1888, Amsterdam, Neth.—died March 10, 1966, Groningen), Dutch physicist, winner of the Nobel Prize for Physics in 1953 for his invention of the phase-contrast microscope, an instrument that permits the study of internal cell structure without the need to stain and thus kill the cells.

Zernike obtained a doctorate from the University of Amsterdam in 1915. He became an assistant at the State University of Groningen in 1913 and served as a full professor there from 1920 to 1958. His earliest work in optics was concerned with astronomical telescopes. While studying the flaws that occur in some diffraction gratings because of the imperfect spacing of engraved lines, he discovered the phase-contrast principle. He noted that he could distinguish the light rays that passed through different transparent materials. He built a microscope using that principle in 1938. In 1952 Zernike was awarded the Rumford Medal of the Royal Society of London.

-1959.jpg)

It appears to me that if one wants to make progress in mathematics, one should study the masters and not the pupils. - Niels Henrik Abel.

Nothing is better than reading and gaining more and more knowledge - Stephen William Hawking.

Offline

#864 2021-02-22 00:20:47

- Jai Ganesh

- Administrator

- Registered: 2005-06-28

- Posts: 52,766

Re: crème de la crème

830) Hermann Staudinger

Hermann Staudinger, (born March 23, 1881, Worms, Germany—died September 8, 1965, Freiburg im Breisgau, West Germany [now Germany]), German chemist who won the 1953 Nobel Prize for Chemistry for demonstrating that polymers are long-chain molecules. His work laid the foundation for the great expansion of the plastics industry later in the 20th century.

Staudinger studied chemistry at the universities of Darmstadt and Munich, and he received a Ph.D. from the University of Halle in 1903. He held academic posts at the universities of Strassburg (now Strasbourg) and Karlsruhe before joining the faculty at the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology in Zürich in 1912. He left the institute in 1926 to become a lecturer at the Albert Ludwig University of Freiburg im Breisgau, where in 1940 an Institute for Macromolecular Chemistry was established under his directorship. Staudinger’s wife, the Latvian plant physiologist Magda Woit, was his coworker and coauthor. He retired in 1951.

Staudinger’s first discovery was that of the highly reactive organic compounds known as ketenes. His work on polymers began with research he conducted for the German chemical firm BASF on the synthesis of isoprene (1910), the monomer of which natural rubber is composed. The prevalent belief at the time was that rubber and other polymers are composed of small molecules that are held together by “secondary” valences or other forces. In 1922 Staudinger and J. Fritschi proposed that polymers are actually giant molecules (macromolecules) that are held together by normal covalent bonds, a concept that met with resistance from many authorities. Throughout the 1920s, the researches of Staudinger and others showed that small molecules form long, chainlike structures (polymers) by chemical interaction and not simply by physical aggregation. Staudinger showed that such linear molecules could be synthesized by a variety of processes and that they could maintain their identity even when subject to chemical modification.

Staudinger’s pioneering work provided the theoretical basis for polymer chemistry and greatly contributed to the development of modern plastics. His researches on polymers eventually contributed to the development of molecular biology, which seeks to understand the structure of proteins and other macromolecules found in living organisms. Staudinger wrote numerous papers and books, including Arbeitserinnerungen (1961; “Working Memories”). Two of his students, Leopold Ružička and Tadeus Reichstein, also won Nobel Prizes.

It appears to me that if one wants to make progress in mathematics, one should study the masters and not the pupils. - Niels Henrik Abel.

Nothing is better than reading and gaining more and more knowledge - Stephen William Hawking.

Offline

#865 2021-02-24 00:08:06

- Jai Ganesh

- Administrator

- Registered: 2005-06-28

- Posts: 52,766

Re: crème de la crème

831) Sir Hans Adolf Krebs

Sir Hans Adolf Krebs, (born Aug. 25, 1900, Hildesheim, Ger.—died Nov. 22, 1981, Oxford, Eng.), German-born British biochemist who received (with Fritz Lipmann) the 1953 Nobel Prize for Physiology or Medicine for the discovery in living organisms of the series of chemical reactions known as the tricarboxylic acid cycle (also called the citric acid cycle, or Krebs cycle). These reactions involve the conversion—in the presence of oxygen—of substances that are formed by the breakdown of sugars, fats, and protein components to carbon dioxide, water, and energy-rich compounds.

At the University of Freiburg (1932), Krebs discovered (with the German biochemist Kurt Henseleit) a series of chemical reactions (now known as the urea cycle) by which ammonia is converted to urea in mammalian tissue; the urea, far less toxic than ammonia, is subsequently excreted in the urine of most mammals. This cycle also serves as a major source of the amino acid arginine.

The son of a Jewish physician, Krebs was forced in 1933 to leave Nazi Germany for England, where he continued his research at the University of Cambridge (1933–35). At Sheffield University, Yorkshire (1935–54), Krebs measured the amounts of certain four-carbon and six-carbon acids generated in pigeon liver and breast muscle when sugars are oxidized completely to yield carbon dioxide, water, and energy.

In 1937 Krebs demonstrated the existence of a cycle of chemical reactions that combines the end-product of sugar breakdown, later shown to be an “activated” form of the two-carbon acetic acid, with the four-carbon oxaloacetic acid to form citric acid. The cycle regenerates oxaloacetic acid through a series of intermediate compounds while liberating carbon dioxide and electrons that are immediately utilized to form high-energy phosphate bonds in the form of adenosine triphosphate (ATP; the chemical-energy reservoir of the cell). The discovery of the tricarboxylic acid cycle, which is central to nearly all metabolic reactions and the source of two-thirds of the food-derived energy in higher organisms, was of vital importance to a basic understanding of cell metabolism and molecular biology.

Krebs served on the faculty of the University of Oxford from 1954 to 1967. He wrote (with the British biochemist Hans Kornberg) ‘Energy Transformations in Living Matter’ (1957) and also coauthored (with Anne Martin) ‘Reminiscences and Reflections’ (1981). He was knighted in 1958, and the Royal Society awarded him its Copley Medal in 1961.

It appears to me that if one wants to make progress in mathematics, one should study the masters and not the pupils. - Niels Henrik Abel.

Nothing is better than reading and gaining more and more knowledge - Stephen William Hawking.

Offline

#866 2021-02-26 00:11:39

- Jai Ganesh

- Administrator

- Registered: 2005-06-28

- Posts: 52,766

Re: crème de la crème

832) Fritz Albert Lipmann

Fritz Albert Lipmann, (born June 12, 1899, Königsberg, Ger. [now Kaliningrad, Russia]—died July 24, 1986, Poughkeepsie, N.Y., U.S.), German-born American biochemist, who received (with Sir Hans Krebs) the 1953 Nobel Prize for Physiology or Medicine for the discovery of coenzyme A, an important catalytic substance involved in the cellular conversion of food into energy.

Lipmann earned an M.D. degree (1924) and a Ph.D. degree (1927) from the University of Berlin. He conducted research in the laboratory of the biochemist Otto Meyerhof at the University of Heidelberg (1927–30) and then did research at the Biological Institute of the Carlsberg Foundation (Carlsbergfondets Biologiske Institut), Copenhagen (1932–39), and at the Cornell Medical School, New York City (1939–41).

At Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston (1941–57), where he directed the biochemistry research department, and as professor of biological chemistry at the Harvard Medical School (1949–57), Lipmann found a catalytically active, heat-stable factor in pigeon liver extracts. He subsequently isolated (1947), named, and determined the molecular structure (1953) of this factor, coenzyme A (or CoA), which is now known to be bound to acetic acid as the end product of sugar and fat breakdown in the absence of oxygen. Coenzyme A is one of the most important substances involved in cellular metabolism; it helps in the conversion of amino acids, steroids, fatty acids, and hemoglobins into energy.

Lipmann taught or conducted research at the Rockefeller Institute, now Rockefeller University, New York City, from 1957 until his death.

It appears to me that if one wants to make progress in mathematics, one should study the masters and not the pupils. - Niels Henrik Abel.

Nothing is better than reading and gaining more and more knowledge - Stephen William Hawking.

Offline

#867 2021-02-28 00:18:25

- Jai Ganesh

- Administrator

- Registered: 2005-06-28

- Posts: 52,766

Re: crème de la crème

833) Max Born

Max Born, (born Dec. 11, 1882, Breslau, Ger. [now Wrocław, Pol.]—died Jan. 5, 1970, Göttingen, W.Ger.), German physicist who shared the Nobel Prize for Physics in 1954 with Walther Bothe for his probabilistic interpretation of quantum mechanics.

Born came from an upper-middle-class, assimilated, Jewish family. At first he was considered too frail to attend public school, so he was tutored at home before being allowed to attend the König Wilhelm Gymnasium in Breslau. Thereafter he continued his studies in physics and mathematics at universities in Breslau, Heidelberg, Zürich, and Göttingen. At the University of Göttingen he wrote his dissertation (1906), on the stability of elastic wires and tapes, under the direction of the mathematician Felix Klein, for which he was awarded a doctorate in 1907.

After brief service in the army and a stay at the University of Cambridge, where he worked with physicists Joseph Larmor and J.J. Thomson, Born returned to Breslau for the academic year 1908–09 and began an extensive study of Albert Einstein’s theory of special relativity. On the strength of his papers in this field, Born was invited back to Göttingen as an assistant to the mathematical physicist Hermann Minkowski. In 1912 Born met Hedwig Ehrenberg, whom he married a year later. Three children, two girls and a boy, were born from the union. It was a troubled relationship, and Born and his wife often lived apart.

In 1915 Born accepted a professorship to assist physicist Max Planck at the University of Berlin, but World War I intervened and he was drafted into the German army. Nonetheless, while an officer in the army, he found time to publish his first book, Dynamik der Kristallgitter (1915; Dynamics of Crystal Lattices).

In 1919 Born was appointed to a full professorship at the University of Frankfurt am Main, and in 1921 he accepted the position of professor of theoretical physics at the University of Göttingen. James Franck had been appointed professor of experimental physics at Göttingen the previous year. The two of them made the University of Göttingen one of the most important centres for the study of atomic and molecular phenomena. A measure of Born’s influence can be gauged by the students and assistants who came to work with him—among them, Wolfgang Pauli, Werner Heisenberg, Pascual Jordan, Enrico Fermi, Fritz London, P.A.M. Dirac, Victor Weisskopf, J. Robert Oppenheimer, Walter Heitler, and Maria Goeppert-Mayer.

The Göttingen years were Born’s most creative and seminal. In 1912 Born and Hungarian engineer Theodore von Karman formulated the dynamics of a crystal lattice, which incorporated the symmetry properties of the lattice, allowed the imposition of quantum rules, and permitted thermal properties of the crystal to be calculated. This work was elaborated when Born was in Göttingen, and it formed the basis of the modern theory of lattice dynamics.

In 1925 Heisenberg gave Born a copy of the manuscript of his first paper on quantum mechanics, and Born immediately recognized that the mathematical entities with which Heisenberg had represented the observable physical quantities of a particle—such as its position, momentum, and energy—were matrices. Joined by Heisenberg and Jordan, Born formulated all the essential aspects of quantum mechanics in its matrix version. A short time later, Erwin Schrödinger formulated a version of quantum mechanics based on his wave equation. It was soon proved that the two formulations were mathematically equivalent. What remained unclear was the meaning of the wave function that appeared in Schrödinger’s equation. In 1926 Born submitted two papers in which he formulated the quantum mechanical description of collision processes and found that in the case of the scattering of a particle by a potential, the wave function at a particular spatiotemporal location should be interpreted as the probability amplitude of finding the particle at that specific space-time point. In 1954 he was awarded the Nobel Prize for this work.

Born remained at Göttingen until April 1933, when all Jews were dismissed from their academic posts in Germany. Born and his family went to England, where he accepted a temporary lectureship at Cambridge. In 1936 he was appointed Tait Professor of Natural Philosophy at the University of Edinburgh. He became a British citizen in 1939 and remained at Edinburgh until his retirement in 1953. The next year, he and his wife moved to Bad Pyrmont, a small spa town near Göttingen.

It appears to me that if one wants to make progress in mathematics, one should study the masters and not the pupils. - Niels Henrik Abel.

Nothing is better than reading and gaining more and more knowledge - Stephen William Hawking.

Offline

#868 2021-03-01 00:07:45

- Jai Ganesh

- Administrator

- Registered: 2005-06-28

- Posts: 52,766

Re: crème de la crème

834) Walther Bothe

Walther Bothe, in full Walther Wilhelm Georg Bothe, (born Jan. 8, 1891, Oranienburg, Ger.—died Feb. 8, 1957, Heidelberg, W.Ger.), German physicist who shared the Nobel Prize for Physics in 1954 with Max Born for his invention of a new method of detecting subatomic particles and for other resulting discoveries.

Bothe taught at the universities of Berlin (1920–31), Giessen (1931–34), and Heidelberg (1934–57). In 1925 he and Hans Geiger used two Geiger counters to gather data on the Compton effect—the dependence of the increase in the wavelength of a beam of X rays upon the angle through which the beam is scattered as a result of collision with electrons. Their experiments, which simultaneously measured the energies and directions of single photons and electrons emerging from individual collisions, refuted a statistical interpretation of the Compton effect and definitely established the particle nature of electromagnetic radiation.

With the astronomer Werner Kolhörster, Bothe again applied this coincidence-counting method in 1929 and found that cosmic rays are not composed exclusively of gamma rays, as was previously believed. In 1930 Bothe discovered an unusual radiation emitted by beryllium when it is bombarded with alpha particles. This radiation was later identified by Sir James Chadwick as the neutron.

During World War II Bothe was one of the leaders of German research on nuclear energy. He was responsible for the planning and building of Germany’s first cyclotron, which was completed in 1943.

It appears to me that if one wants to make progress in mathematics, one should study the masters and not the pupils. - Niels Henrik Abel.

Nothing is better than reading and gaining more and more knowledge - Stephen William Hawking.

Offline

#869 2021-03-03 00:25:31

- Jai Ganesh

- Administrator

- Registered: 2005-06-28

- Posts: 52,766

Re: crème de la crème

835) John Franklin Enders

John Franklin Enders, (born Feb. 10, 1897, West Hartford, Conn., U.S.—died Sept. 8, 1985, Waterford, Conn.), American virologist and microbiologist who, with Frederick C. Robbins and Thomas H. Weller, was awarded the Nobel Prize for Physiology or Medicine for 1954 for his part in cultivating the poliomyelitis virus in nonnervous-tissue cultures, a preliminary step to the development of the polio vaccine.

Enders was a student of English literature at Harvard University (M.A., 1922) before he turned to bacterial studies there (Ph.D., 1930). His early researches contributed new and basic knowledge to problems of tuberculosis, pneumococcal infections, and resistance to bacterial diseases. In 1929 he joined the Harvard faculty as an assistant in the department of bacteriology and immunology, later advancing to assistant professor (1935) and associate professor (1942) in the university’s medical school.

In World War II he was a civilian consultant on infectious diseases to the U.S. War Department. From 1945 to 1949 he served the U.S. Army in a like capacity, with particular work on the mumps virus and rickettsial diseases. During this period Enders, with his coworkers Weller and Robbins, began research into new methods of producing in quantity the virus of poliomyelitis. Until that time the only effective method of growing the virus had been in the nerve tissue of living monkeys, and the vaccine thus produced had been proved dangerous to humans. The Enders–Weller–Robbins method of production, achieved in test tubes using cultures of nonnerve tissue from human embryos and monkeys, led to the development of the Salk vaccine for polio in 1954. Similarly, their production in the late 1950s of a vaccine against the measles led to the development of a licensed vaccine in the United States in 1963. Much of Enders’ research on viruses was conducted at the Children’s Hospital in Boston, where he had established a laboratory in 1946.

It appears to me that if one wants to make progress in mathematics, one should study the masters and not the pupils. - Niels Henrik Abel.

Nothing is better than reading and gaining more and more knowledge - Stephen William Hawking.

Offline

#870 2021-03-05 00:21:50

- Jai Ganesh

- Administrator

- Registered: 2005-06-28

- Posts: 52,766

Re: crème de la crème

836) Frederick Chapman Robbins

Frederick Chapman Robbins, (born August 25, 1916, Auburn, Alabama, U.S.—died August 4, 2003, Cleveland, Ohio), American pediatrician and virologist who received (with John Enders and Thomas Weller) the 1954 Nobel Prize for Physiology or Medicine for successfully cultivating poliomyelitis virus in tissue cultures. This accomplishment made possible the production of polio vaccines, the development of sophisticated diagnostic methods, and the isolation of new viruses.

A graduate of Harvard University Medical School (1940), Robbins served in the United States, Italy, and North Africa during World War II (1942–46) as chief of the U.S. Army’s 15th medical general laboratory virus and rickettsia section, where he investigated epidemics of infectious hepatitis, typhus, and Q fever.

After joining Enders and Weller at the Children’s Hospital in Boston in 1948, Robbins helped solve the difficult problem of propagating viruses—then known to grow only in living organisms—in laboratory suspensions of actively metabolizing cells in nutrient solutions. At that time it was believed that the virus responsible for poliomyelitis grew and multiplied only in mammalian nerve tissue, which is highly difficult to maintain outside the living animal. By 1952 Robbins and his colleagues had succeeded in cultivating the virus in mixtures of human embryonic skin and muscle tissue suspended in cell cultures, dramatically demonstrating that the polio virus subsists in extraneural tissue, only later attacking the lower part of the brain and sections of the spinal cord.

Robbins served as director of the department of pediatrics and contagious diseases at the Cleveland Metropolitan General Hospital (1952–66) and as professor of pediatrics (1952–80) and dean (1966–80) at the Case Western Reserve University School of Medicine, Cleveland, Ohio. He later served as president of the Institute of Medicine of the National Academy of Sciences (1980–85).

It appears to me that if one wants to make progress in mathematics, one should study the masters and not the pupils. - Niels Henrik Abel.

Nothing is better than reading and gaining more and more knowledge - Stephen William Hawking.

Offline

#871 2021-03-07 00:03:54

- Jai Ganesh

- Administrator

- Registered: 2005-06-28

- Posts: 52,766

Re: crème de la crème

837) Thomas H. Weller

Thomas H. Weller, in full Thomas Huckle Weller, (born June 15, 1915, Ann Arbor, Mich., U.S.—died Aug. 23, 2008, Needham, Mass.), American physician and virologist who was the corecipient (with John Enders and Frederick Robbins) of the Nobel Prize for Physiology or Medicine in 1954 for the successful cultivation of poliomyelitis virus in tissue cultures. This made it possible to study the virus “in the test tube”—a procedure that led to the development of polio vaccines.

After his education at the University of Michigan at Ann Arbor (A.B., 1936; M.S., 1937) and Harvard University (M.D., 1940), Weller became a teaching fellow at the Harvard Medical School (1940–42) and served in the U.S. Army Medical Corps during World War II. He was appointed assistant director of Enders’ infectious diseases laboratory at the Children’s Medical Center, Boston (1949–55), and, working with Enders and Robbins, soon achieved the propagation of poliomyelitis virus in laboratory suspensions of human embryonic skin and muscle tissue. He was also the first (with the American physician Franklin Neva) to achieve the laboratory propagation of rubella (German measles) virus and to isolate chicken pox virus from human cell cultures. Weller became professor of tropical public health at Harvard University in 1954 and from 1966 to 1981 served also as director of the Center for the Prevention of Infectious Diseases at the Harvard University School of Public Health. Weller’s autobiography, ‘Growing Pathogens in Tissue Cultures: Fifty Years in Academic Tropical Medicine, Pediatrics, and Virology’, was published in 2004.

It appears to me that if one wants to make progress in mathematics, one should study the masters and not the pupils. - Niels Henrik Abel.

Nothing is better than reading and gaining more and more knowledge - Stephen William Hawking.

Offline

#872 2021-03-09 00:09:40

- Jai Ganesh

- Administrator

- Registered: 2005-06-28

- Posts: 52,766

Re: crème de la crème

838) Willis Eugene Lamb, Jr.

Willis Eugene Lamb, Jr., (born July 12, 1913, Los Angeles, Calif., U.S.—died May 15, 2008, Tucson, Ariz.), American physicist and corecipient, with Polykarp Kusch, of the 1955 Nobel Prize for Physics for experimental work that spurred refinements in the quantum theories of electromagnetic phenomena.

Lamb joined the faculty of Columbia University, New York City, in 1938 and worked in the Radiation Laboratory there during World War II. Though the quantum mechanics of P.A.M. Dirac had predicted the hyperfine structure of the lines that appear in the spectrum (dispersed light, as by a prism), Lamb applied new methods to measure the lines and in 1947 found their positions to be slightly different from what had been predicted. While a professor of physics (1951–56) at Stanford University, California, Lamb devised microwave techniques for examining the hyperfine structure of the spectral lines of helium. He was a professor of theoretical physics at the University of Oxford until 1962, when he was appointed a professor of physics at Yale University. In 1974 he became a professor of physics and optical sciences at the University of Arizona; he retired as professor emeritus in 2002.

It appears to me that if one wants to make progress in mathematics, one should study the masters and not the pupils. - Niels Henrik Abel.

Nothing is better than reading and gaining more and more knowledge - Stephen William Hawking.

Offline

#873 2021-03-11 00:21:22

- Jai Ganesh

- Administrator

- Registered: 2005-06-28

- Posts: 52,766

Re: crème de la crème

839) Ernest Thomas Sinton Walton

Ernest Thomas Sinton Walton, (born Oct. 6, 1903, Dungarvan, County Waterford, Ire.—died June 25, 1995, Belfast, N.Ire.), Irish physicist, corecipient, with Sir John Douglas math of England, of the 1951 Nobel Prize for Physics for the development of the first nuclear particle accelerator, known as the math-Walton generator.

After studying at the Methodist College, Belfast, and graduating in mathematics and experimental science from Trinity College, Dublin (1926), Walton went in 1927 to Trinity College, Cambridge, where he was to work with math in the Cavendish Laboratory under Lord Rutherford until 1934. In 1928 he attempted two methods of high-energy particle acceleration. Both failed, mainly because the available power sources could not generate the necessary energies, but his methods were later developed and used in the betatron and the linear accelerator. Then in 1929 math and Walton devised an accelerator that generated large numbers of particles at lower energies. With this device in 1932 they disintegrated lithium nuclei with protons, the first artificial nuclear reaction not utilizing radioactive substances.

After gaining his Ph.D. at Cambridge, Walton returned to Trinity College, Dublin, in 1934, where he remained as a fellow for the next 40 years and a fellow emeritus thereafter. He was Erasmus Smith professor of natural and experimental philosophy from 1946 to 1974 and chairman of the School of Cosmic Physics at the Dublin Institute for Advanced Studies after 1952.

It appears to me that if one wants to make progress in mathematics, one should study the masters and not the pupils. - Niels Henrik Abel.

Nothing is better than reading and gaining more and more knowledge - Stephen William Hawking.

Offline

#874 2021-03-13 00:21:14

- Jai Ganesh

- Administrator

- Registered: 2005-06-28

- Posts: 52,766

Re: crème de la crème

840) Polykarp Kusch

Polykarp Kusch, (born Jan. 26, 1911, Blankenburg, Ger.—died March 20, 1993, Dallas, Texas, U.S.), German-American physicist who, with Willis E. Lamb, Jr., was awarded the Nobel Prize for Physics in 1955 for his accurate determination that the magnetic moment of the electron is greater than its theoretical value, thus leading to reconsideration of and innovations in quantum electrodynamics.

Kusch was brought to the United States in 1912 and became a citizen in 1922. In 1937, at Columbia University, he worked with the physicist Isidor I. Rabi on studies of the effects of magnetic fields on beams of atoms. He spent the wartime years in research on radar and returned to Columbia in 1946 as professor of physics, a position he held until 1972. Among other posts held by Kusch at Columbia were department chairman (1949–52, 1960–63), director of the radiation laboratory (1952–60), and academic vice president and provost (1969–72). In 1972 he took a position as professor at the University of Texas, Dallas, where he remained until his retirement in 1982.

In 1947, through precise atomic beam studies, Kusch demonstrated that the magnetic properties of the electron were not in agreement with existing theories. Subsequently, he made accurate measurements of the magnetic moment of the electron and its behaviour in hydrogen. In work characterized by great accuracy and reliability, he measured numerous atomic, molecular, and nuclear properties by radio-frequency beam techniques.

It appears to me that if one wants to make progress in mathematics, one should study the masters and not the pupils. - Niels Henrik Abel.

Nothing is better than reading and gaining more and more knowledge - Stephen William Hawking.

Offline

#875 2021-03-15 00:09:48

- Jai Ganesh

- Administrator

- Registered: 2005-06-28

- Posts: 52,766

Re: crème de la crème

841) Vincent du Vigneaud

Vincent du Vigneaud, (born May 18, 1901, Chicago, Illinois, U.S.—died December 11, 1978, White Plains, New York), American biochemist and winner of the Nobel Prize for Chemistry in 1955 for the isolation and synthesis of two pituitary hormones: vasopressin, which acts on the muscles of the blood vessels to cause elevation of blood pressure; and oxytocin, the principal agent causing contraction of the uterus and secretion of milk.

Du Vigneaud studied at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, took a doctorate from the University of Rochester, New York (1927), and then studied at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute, Berlin, and the University of Edinburgh. He headed the biochemistry department of the George Washington University Medical School, Washington, D.C. (1932–38), and was professor and head of the department of biochemistry at the Cornell University Medical College, New York City (1938–67), and professor of chemistry at Cornell University, Ithaca, New York (1967–75).

Du Vigneaud and his staff at Cornell helped identify the chemical structure of the hormone insulin in the late 1930s, and in the early 1940s they established the structure of the sulfur-bearing vitamin biotin. Later that decade, they isolated vasopressin and oxytocin and analyzed both those hormones’ chemical structure. Du Vigneaud found that the oxytocin molecule contains only eight different amino acids (nine amino acids in total, whereby a disulfide bond forms a link between two cysteines), in contrast to the hundreds of amino acids most other proteins contain. In 1953 he was able to synthesize oxytocin, becoming the first to achieve the synthesis of a protein hormone. In 1946 du Vigneaud and his colleagues at Cornell achieved another breakthrough, the synthesis of penicillin.

It appears to me that if one wants to make progress in mathematics, one should study the masters and not the pupils. - Niels Henrik Abel.

Nothing is better than reading and gaining more and more knowledge - Stephen William Hawking.

Offline