Math Is Fun Forum

You are not logged in.

- Topics: Active | Unanswered

#926 2021-06-21 00:28:30

- Jai Ganesh

- Administrator

- Registered: 2005-06-28

- Posts: 53,161

Re: crème de la crème

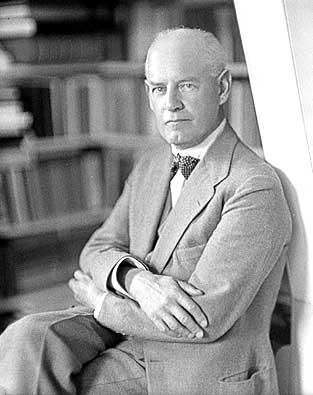

892) Sinclair Lewis

Sinclair Lewis, in full Harry Sinclair Lewis, (born Feb. 7, 1885, Sauk Centre, Minn., U.S.—died Jan. 10, 1951, near Rome, Italy), American novelist and social critic who punctured American complacency with his broadly drawn, widely popular satirical novels. He won the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1930, the first given to an American.

Lewis graduated from Yale University (1907) and was for a time a reporter and also worked as an editor for several publishers. His first novel, ‘Our Mr. Wrenn’ (1914), attracted favourable criticism but few readers. At the same time he was writing with ever-increasing success for such popular magazines as ‘The Saturday Evening Post’ and ‘Cosmopolitan’, but he never lost sight of his ambition to become a serious novelist. He undertook the writing of Main Street as a major effort, assuming that it would not bring him the ready rewards of magazine fiction. Yet its publication in 1920 made his literary reputation. Main Street’ is seen through the eyes of Carol Kennicott, an Eastern girl married to a Midwestern doctor who settles in Gopher Prairie, Minnesota (modeled on Lewis’ hometown of Sauk Centre). The power of the book derives from Lewis’ careful rendering of local speech, customs, and social amenities. The satire is double-edged—directed against both the townspeople and the superficial intellectualism that despises them. In the years following its publication, ‘Main Street’ became not just a novel but the textbook on American provincialism.

In 1922 Lewis published ‘Babbitt’, a study of the complacent American whose individuality has been sucked out of him by Rotary clubs, business ideals, and general conformity. The name Babbitt passed into general usage to represent the optimistic, self-congratulatory, middle-aged businessman whose horizons were bounded by his village limits.

He followed this success with ‘Arrowsmith’ (1925), a satiric study of the medical profession, with emphasis on the frustration of fine scientific ideals. His next important book, ‘Elmer Gantry’ (1927), was an attack on the ignorant, gross, and predatory leaders who had crept into the Protestant church. ‘Dodsworth’ (1929), concerning the experiences of a retired big businessman and his wife on a European tour, offered Lewis a chance to contrast American and European values and the very different temperaments of the man and his wife.

Lewis’ later books were not up to the standards of his work in the 1920s. ‘It Can’t Happen Here’ (1935) dramatized the possibilities of a Fascist takeover of the United States. It was produced as a play by the Federal Theatre with 21 companies in 1936. ‘Kingsblood Royal’ (1947) is a novel of race relations.

In his final years Lewis lived much of the time abroad. His reputation declined steadily after 1930. His two marriages (the second was to the political columnist Dorothy Thompson) ended in divorce, and he drank excessively.

It appears to me that if one wants to make progress in mathematics, one should study the masters and not the pupils. - Niels Henrik Abel.

Nothing is better than reading and gaining more and more knowledge - Stephen William Hawking.

Offline

#927 2021-06-23 00:07:47

- Jai Ganesh

- Administrator

- Registered: 2005-06-28

- Posts: 53,161

Re: crème de la crème

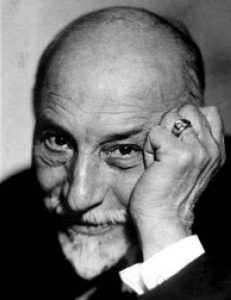

893) Erik Axel Karlfeldt

Erik Axel Karlfeldt, (born July 20, 1864, Folkärna, Sweden—died April 8, 1931, Stockholm), Swedish poet whose essentially regional, tradition-bound poetry was extremely popular and won him the Nobel Prize for Literature posthumously in 1931; he had refused it in 1918, at least in part because of his position as secretary to the Swedish Academy, which awards the prize.

Karlfeldt’s strong ties to the peasant culture of his rural homeland remained a dominant influence on him all his life. The peasants whom he portrayed are, as one critic put it, “in harmony with nature and the seasons”; their culture is sometimes threatened by the erotic, anarchic Pan. Karlfeldt published his most important works in six volumes of verse: ‘Vildmarks- och kärleksvisor’ (1895; “Songs of Wilderness and of Love”), ‘Fridolins visor’ (1898; “Fridolin’s Songs”), ‘Fridolins lustgård’ (1901; “Fridolin’s Pleasure Garden”), ‘Flora och Pomona’ (1906; “Flora and Pomona”), ‘Flora och Bellona’ (1918; “Flora and Bellona”), and finally, four years before his death, ‘Hösthorn’ (1927; “The Horn of Autumn”). Some of his poems have been published in English translation in ‘Arcadia Borealis: Selected Poems of Erik Axel Karlfeldt’ (1938). He was a beloved Neoromantic poet whose occasional artistic complexity was emotional rather than intellectual. In time, even some of his admirers criticized him for employing his gifts so exclusively in the service of a dying local culture.

It appears to me that if one wants to make progress in mathematics, one should study the masters and not the pupils. - Niels Henrik Abel.

Nothing is better than reading and gaining more and more knowledge - Stephen William Hawking.

Offline

#928 2021-06-25 00:14:52

- Jai Ganesh

- Administrator

- Registered: 2005-06-28

- Posts: 53,161

Re: crème de la crème

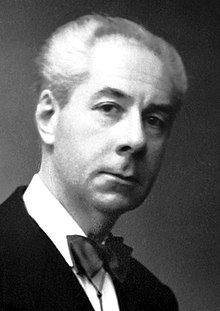

894) John Galsworthy

John Galsworthy, (born Aug. 14, 1867, Kingston Hill, Surrey, Eng.—died Jan. 31, 1933, Grove Lodge, Hampstead), English novelist and playwright, winner of the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1932.

Galsworthy’s family, of Devonshire farming stock traceable to the 16th century, had made a comfortable fortune in property in the 19th century. His father was a solicitor. Educated at Harrow and New College, Oxford, Galsworthy was called to the bar in 1890. With a view to specializing in marine law, he took a voyage around the world, during which he encountered Joseph Conrad, then mate of a merchant ship. They became lifelong friends. Galsworthy found law uncongenial and took to writing. For his first works, From the Four Winds (1897), a collection of short stories, and the novel Jocelyn (1898), both published at his own expense, he used the pseudonym John Sinjohn. ‘The Island Pharisees’ (1904) was the first book to appear under his own name.

‘The Man of Property’ (1906) began the novel sequence known as ‘The Forsyte Saga’, by which Galsworthy is chiefly remembered; others in the same series are “Indian Summer of a Forsyte” (1918, in ‘Five Tales’), ‘In Chancery’ (1920), ‘Awakening’ (1920), and ‘To Let’ (1921). The saga chronicles the lives of three generations of a large, upper middle-class family at the turn of the century. Having recently risen to wealth and success in the profession and business world, the Forsytes are tenaciously clannish and anxious to increase their wealth. The novels imply that their desire for property is morally wrong. The saga intersperses diatribes against wealth with lively passages describing character and background. In The Man of Property’, Galsworthy attacks the Forsytes through the character of Soames Forsyte, a solicitor who considers his wife Irene as a mere form of property. Irene finds her husband physically unattractive and falls in love with a young architect who dies. The other two novels of the saga, ‘In Chancery’ and ‘To Let’, trace the subsequent divorce of Soames and Irene, the second marriages they make, and the eventual romantic entanglements of their children. The story of the Forsyte family after World War I was continued in ‘The White Monkey’ (1924), ‘The Silver Spoon’ (1926), and ‘Swan Song’ (1928), collected in ‘A Modern Comedy’ (1929). Galsworthy’s other novels include ‘The Country House’ (1907), ‘The Patrician’ (1911), and ‘The Freelands’ (1915).

Galsworthy was also a successful dramatist, his plays, written in a naturalistic style, usually examining some controversial ethical or social problem. They include ‘The Silver Box’ (1906), which, like many of his other works, has a legal theme and depicts a bitter contrast of the law’s treatment of the rich and the poor; ‘Strife’ (1909), a study of industrial relations; ‘Justice’ (1910), a realistic portrayal of prison life that roused so much feeling that it led to reform; and ‘Loyalties’ (1922), the best of his later plays. He also wrote verse.

In 1905 Galsworthy married Ada Pearson, the divorced wife of his first cousin, A.J. Galsworthy. Galsworthy had, in secret, been closely associated with his future wife for about ten years before their marriage. Irene in ‘The Forsyte Saga’ is to some extent a portrait of Ada Galsworthy, although her first husband was wholly unlike Soames Forsyte.

Galsworthy’s novels, by their abstention from complicated psychology and their greatly simplified social viewpoint, became accepted as faithful patterns of English life for a time. Galsworthy is remembered for this evocation of Victorian and Edwardian upper middle-class life and for his creation of Soames Forsyte, a dislikable character who nevertheless compels the reader’s sympathy.

A television serial of ‘The Forsyte Saga’ by the British Broadcasting Corporation achieved immense popularity in Great Britain in 1967 and later in many other nations, especially the United States, reviving interest in an author whose reputation had plummeted after his death.

It appears to me that if one wants to make progress in mathematics, one should study the masters and not the pupils. - Niels Henrik Abel.

Nothing is better than reading and gaining more and more knowledge - Stephen William Hawking.

Offline

#929 2021-06-27 00:15:10

- Jai Ganesh

- Administrator

- Registered: 2005-06-28

- Posts: 53,161

Re: crème de la crème

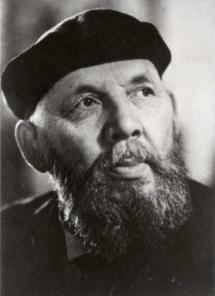

895) Ivan Bunin

Ivan Bunin, in full Ivan Alekseyevich Bunin, (born October 10 [October 22, New Style], 1870, Voronezh, Russia—died November 8, 1953, Paris, France), poet and novelist, the first Russian to receive the Nobel Prize for Literature (1933), and one of the finest of Russian stylists.

Bunin, the descendant of an old noble family, spent his childhood and youth in the Russian provinces. He attended secondary school in Yelets, in western Russia, but did not graduate; his older brother subsequently tutored him. Bunin began publishing poems and short stories in 1887, and in 1889–92 he worked for the newspaper Orlovsky Vestnik (“The Orlovsky Herald”). His first book, Stikhotvoreniya: 1887–1891 (“Poetry: 1887–1891”), appeared in 1891 as a supplement to that newspaper. In the mid-1890s he was strongly drawn to the ideas of the novelist Leo Tolstoy, whom he met in person. During this period Bunin gradually entered the Moscow and St. Petersburg literary scenes, including the growing Symbolist movement. Bunin’s Listopad (1901; “Falling Leaves”), a book of poetry, testifies to his association with the Symbolists, primarily Valery Bryusov. However, Bunin’s work had more in common with the traditions of classical Russian literature of the 19th century, of which his older contemporaries Tolstoy and Anton Chekhov were models.

By the beginning of the 20th century, Bunin had become one of Russia’s most popular writers. His sketches and stories Antonovskiye yabloki (1900; “Antonov Apples”), Grammatika lyubvi (1929; “Grammar of Love”), Lyogkoye dykhaniye (1922; “Light Breathing”), Sny Changa (1916; “The Dreams of Chang”), Sukhodol (1912; “Dry Valley”), Derevnya (1910; “The Village”), and Gospodin iz San-Frantsisko (1916; “The Gentleman from San Francisco”) show Bunin’s penchant for extreme precision of language, delicate description of nature, detailed psychological analysis, and masterly control of plot. While his democratic views gave rise to criticism in Russia, they did not turn him into a politically engaged writer. Bunin also believed that change was inevitable in Russian life. His urge to keep his independence is evident in his break with the writer Maxim Gorky and other old friends after the Russian Revolution of 1917, which he perceived as the triumph of the basest side of the Russian people.

Bunin’s articles and diaries of 1917–20 are a record of Russian life during its years of terror. In May 1918 he left Moscow and settled in Odessa (now in Ukraine), and at the beginning of 1920 he emigrated first to Constantinople (now Istanbul) and then to France, where he lived for the rest of his life. There he became one of the most famous Russian émigré writers. His stories, the novella Mitina lyubov (1925; Mitya’s Love), and the autobiographical novel Zhizn math (The Life of math)—which Bunin began writing during the 1920s and of which he published parts in the 1930s and 1950s—were recognized by critics and Russian readers abroad as testimony of the independence of Russian émigré culture.

Bunin lived in the south of France during World War II, refusing all contact with the Nazis and hiding Jews in his villa. Tyomnye allei (1943; Dark Avenues, and Other Stories), a book of short stories, was one of his last great works. After the end of the war, Bunin was invited to return to the Soviet Union, but he remained in France.Vospominaniya (Memories and Portraits), which appeared in 1950. An unfinished book, O Chekhove (1955; “On Chekhov”; Eng. trans. About Chekhov: The Unfinished Symphony), was published posthumously. Bunin was one of the first Russian émigré writers whose works were published in the Soviet Union after the death of Soviet leader Joseph Stalin.

It appears to me that if one wants to make progress in mathematics, one should study the masters and not the pupils. - Niels Henrik Abel.

Nothing is better than reading and gaining more and more knowledge - Stephen William Hawking.

Offline

#930 2021-06-29 00:05:37

- Jai Ganesh

- Administrator

- Registered: 2005-06-28

- Posts: 53,161

Re: crème de la crème

896) Luigi Pirandello

Luigi Pirandello, (born June 28, 1867, Agrigento, Sicily, Italy—died Dec. 10, 1936, Rome), Italian playwright, novelist, and short-story writer, winner of the 1934 Nobel Prize for Literature. With his invention of the “theatre within the theatre” in the play Sei personaggi in cerca d’autore (1921; Six Characters in Search of an Author), he became an important innovator in modern drama.

Pirandello was the son of a sulfur merchant who wanted him to enter commerce. Pirandello, however, was not interested in business; he wanted to study. He first went to Palermo, the capital of Sicily, and, in 1887, to the University of Rome. After a quarrel with the professor of classics there, he went in 1888 to the University of Bonn, Ger., where in 1891 he gained his doctorate in philology for a thesis on the dialect of Agrigento.

In 1894 his father arranged his marriage to Antonietta Portulano, the daughter of a business associate, a wealthy sulfur merchant. This marriage gave him financial independence, allowing him to live in Rome and to write. He had already published an early volume of verse, Mal giocondo (1889), which paid tribute to the poetic fashions set by Giosuè Carducci. This was followed by other volumes of verse, including Pasqua di Gea (1891; dedicated to Jenny Schulz-Lander, the love he had left behind in Bonn) and a translation of J.W. von Goethe’s Roman Elegies (1896; Elegie romane). But his first significant works were short stories, which at first he contributed to periodicals without payment.

In 1903 a landslide shut down the sulfur mine in which his wife’s and his father’s capital was invested. Suddenly poor, Pirandello was forced to earn his living not only by writing but also by teaching Italian at a teacher’s college in Rome. As a further result of the financial disaster, his wife developed a persecution mania, which manifested itself in a frenzied jealousy of her husband. His torment ended only with her removal to a sanatorium in 1919 (she died in 1959). It was this bitter experience that finally determined the theme of his most characteristic work, already perceptible in his early short stories—the exploration of the tightly closed world of the forever changeable human personality.

Pirandello’s early narrative style stems from the verismo (“realism”) of two Italian novelists of the late 19th century—Luigi Capuana and Giovanni Verga. The titles of Pirandello’s early collections of short stories—Amori senza amore (1894; “Loves Without Love”) and Beffe della morte e della vita (1902–03; “The Jests of Life and Death”)—suggest the wry nature of his realism that is seen also in his first novels: L’esclusa (1901; The Outcast) and Il turno (1902; Eng. trans. The Merry-Go-Round of Love). Success came with his third novel, often acclaimed as his best, Il fu Mattia Pascal (1904; The Late Mattia Pascal). Although the theme is not typically “Pirandellian,” since the obstacles confronting its hero result from external circumstances, it already shows the acute psychological observation that was later to be directed toward the exploration of his characters’ subconscious.

Pirandello’s understanding of psychology was sharpened by reading such works as Les altérations de la personnalité (1892), by the French experimental psychologist Alfred Binet; and traces of its influence can be seen in the long essay L’umorismo (1908; On Humor), in which he examines the principles of his art. Common to both books is the theory of the subconscious personality, which postulates that what a person knows, or thinks he knows, is the least part of what he is. Pirandello had begun to focus his writing on the themes of psychology even before he knew of the work of Sigmund Freud, the founder of psychoanalysis. The psychological themes used by Pirandello found their most complete expression in the volumes of short stories La trappola (1915; “The Trap”) and E domani, lunedì . . . (1917; “And Tomorrow, Monday . . . ”), and in such individual stories as “Una voce,” “Pena di vivere così,” and “Con altri occhi.”

Meanwhile, he had been writing other novels, notably I vecchi e i giovani (1913; The Old and The Young) and Uno, nessuno e centomila (1925–26; One, None, and a Hundred Thousand). Both are more typical than Il fu Mattia Pascal. The first, a historical novel reflecting the Sicily of the end of the 19th century and the general bitterness at the loss of the ideals of the Risorgimento (the movement that led to the unification of Italy), suffers from Pirandello’s tendency to “discompose” rather than to “compose” (to use his own terms, in L’umorismo), so that individual episodes stand out at the expense of the work as a whole. Uno, nessuno e centomila, however, is at once the most original and the most typical of his novels. It is a surrealistic description of the consequences of the hero’s discovery that his wife (and others) see him with quite different eyes than he does himself. Its exploration of the reality of personality is of a type better known from his plays.

Pirandello wrote over 50 plays. He had first turned to the theatre in 1898 with L’epilogo, but the accidents that prevented its production until 1910 (when it was retitled La morsa) kept him from other than sporadic attempts at drama until the success of Così è (se vi pare) in 1917. This delay may have been fortunate for the development of his dramatic powers. L’epilogo does not greatly differ from other drama of its period, but Così è (se vi pare) began the series of plays that were to make him world famous in the 1920s. Its title can be translated as Right You Are (If You Think You Are). A demonstration, in dramatic terms, of the relativity of truth, and a rejection of the idea of any objective reality not at the mercy of individual vision, it anticipates Pirandello’s two great plays, Six Characters in Search of an Author (1921) and Enrico IV (1922; Henry IV). Six Characters is the most arresting presentation of the typical Pirandellian contrast between art, which is unchanging, and life, which is an inconstant flux. Characters that have been rejected by their author materialize on stage, throbbing with a more intense vitality than the real actors, who, inevitably, distort their drama as they attempt its presentation. And in Henry IV the theme is madness, which lies just under the skin of ordinary life and is, perhaps, superior to ordinary life in its construction of a satisfying reality. The play finds dramatic strength in its hero’s choice of retirement into unreality in preference to life in the uncertain world.

The production of Six Characters in Paris in 1923 made Pirandello widely known, and his work became one of the central influences on the French theatre. French drama from the existentialistic pessimism of Jean Anouilh and Jean-Paul Sartre to the absurdist comedy of Eugène Ionesco and Samuel Beckett is tinged with “Pirandellianism.” His influence can also be detected in the drama of other countries, even in the religious verse dramas of T.S. Eliot.

In 1920 Pirandello said of his own art:

‘I think that life is a very sad piece of buffoonery; because we have in ourselves, without being able to know why, wherefore or whence, the need to deceive ourselves constantly by creating a reality (one for each and never the same for all), which from time to time is discovered to be vain and illusory . . . My art is full of bitter compassion for all those who deceive themselves; but this compassion cannot fail to be followed by the ferocious derision of destiny which condemns man to deception.’

This despairing outlook attained its most vigorous expression in Pirandello’s plays, which were criticized at first for being too “cerebral” but later recognized for their underlying sensitivity and compassion. The plays’ main themes are the necessity and the vanity of illusion, and the multifarious appearances, all of them unreal, of what is presumed to be the truth. A human being is not what he thinks he is, but instead is “one, no one and a hundred thousand,” according to his appearance to this person or that, which is always different from the image of himself in his own mind. Pirandello’s plays reflect the verismo of Capuana and Verga in dealing mostly with people in modest circumstances, such as clerks, teachers, and lodging-house keepers, but from whose vicissitudes he draws conclusions of general human significance.

The universal acclaim that followed Six Characters and Henry IV sent Pirandello touring the world (1925–27) with his own company, the Teatro d’Arte in Rome. It also emboldened him to disfigure some of his later plays (e.g., Ciascuno a suo modo [1924]) by calling attention to himself, just as in some of the later short stories it is the surrealistic and fantastic elements that are accentuated.

After the dissolution, because of financial losses, of the Teatro d’Arte in 1928, Pirandello spent his remaining years in frequent and extensive travel. In his will he requested that there should be no public ceremony marking his death—only “a hearse of the poor, the horse and the coachman.”

It appears to me that if one wants to make progress in mathematics, one should study the masters and not the pupils. - Niels Henrik Abel.

Nothing is better than reading and gaining more and more knowledge - Stephen William Hawking.

Offline

#931 2021-07-01 00:10:26

- Jai Ganesh

- Administrator

- Registered: 2005-06-28

- Posts: 53,161

Re: crème de la crème

897) Eugene O'Neill

Eugene O’Neill, in full Eugene Gladstone O’Neill, (born October 16, 1888, New York, New York, U.S.—died November 27, 1953, Boston, Massachusetts), foremost American dramatist and winner of the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1936. His masterpiece, ‘Long Day’s Journey into Night’ (produced posthumously 1956), is at the apex of a long string of great plays, including ‘Beyond the Horizon’ (1920), ‘Anna Christie’ (1922), ‘Strange Interlude’ (1928), ‘Ah! Wilderness’ (1933), and ‘The Iceman Cometh’ (1946).

Early life

O’Neill was born into the theatre. His father, James O’Neill, was a successful touring actor in the last quarter of the 19th century whose most famous role was that of the Count of Monte Cristo in a stage adaptation of the Alexandre Dumas père novel. His mother, Ella, accompanied her husband back and forth across the country, settling down only briefly for the birth of her first son, James, Jr., and of Eugene.

Eugene, who was born in a hotel, spent his early childhood in hotel rooms, on trains, and backstage. Although he later deplored the nightmare insecurity of his early years and blamed his father for the difficult, rough-and-tumble life the family led—a life that resulted in his mother’s drug addiction—Eugene had the theatre in his blood. He was also, as a child, steeped in the peasant Irish Catholicism of his father and the more genteel, mystical piety of his mother, two influences, often in dramatic conflict, which account for the high sense of drama and the struggle with God and religion that distinguish O’Neill’s plays.

O’Neill was educated at boarding schools—Mt. St. Vincent in the Bronx and Betts Academy in Stamford, Connecticut. His summers were spent at the family’s only permanent home, a modest house overlooking the Thames River in New London, Connecticut. He attended Princeton University for one year (1906–07), after which he left school to begin what he later regarded as his real education in “life experience.” The next six years very nearly ended his life. He shipped to sea, lived a derelict’s existence on the waterfronts of Buenos Aires, Liverpool, and New York City, submerged himself in alcohol, and attempted suicide. Recovering briefly at the age of 24, he held a job for a few months as a reporter and contributor to the poetry column of the New London Telegraph but soon came down with tuberculosis. Confined to the Gaylord Farm Sanitarium in Wallingford, Connecticut, for six months (1912–13), he confronted himself soberly and nakedly for the first time and seized the chance for what he later called his “rebirth.” He began to write plays.

Entry into theatre

O’Neill’s first efforts were awkward melodramas, but they were about people and subjects—prostitutes, derelicts, lonely sailors, God’s injustice to man—that had, up to that time, been in the province of serious novels and were not considered fit subjects for presentation on the American stage. A theatre critic persuaded his father to send him to Harvard to study with George Pierce Baker in his famous playwriting course. Although what O’Neill produced during that year (1914–15) owed little to Baker’s academic instruction, the chance to work steadily at writing set him firmly on his chosen path.

O’Neill’s first appearance as a playwright came in the summer of 1916, in the quiet fishing village of Provincetown, Massachusetts, where a group of young writers and painters had launched an experimental theatre. In their tiny, ramshackle playhouse on a wharf, they produced his one-act sea play ‘Bound East for Cardiff’. The talent inherent in the play was immediately evident to the group, which that fall formed the Playwrights’ Theater in Greenwich Village. Their first bill, on November 3, 1916, included ‘Bound East for Cardiff’—O’Neill’s New York debut. Although he was only one of several writers whose plays were produced by the Playwrights’ Theater, his contribution within the next few years made the group’s reputation. Between 1916 and 1920, the group produced all of O’Neill’s one-act sea plays, along with a number of his lesser efforts. By the time his first full-length play, ‘Beyond the Horizon’, was produced on Broadway, February 2, 1920, at the Morosco Theater, the young playwright already had a small reputation.

‘Beyond the Horizon’ impressed the critics with its tragic realism, won for O’Neill the first of four Pulitzer prizes in drama—others were for ‘Anna Christie’, ‘Strange Interlude’, and ‘Long Day’s Journey into Night’—and brought him to the attention of a wider theatre public. For the next 20 years his reputation grew steadily, both in the United States and abroad; after Shakespeare and Shaw, O’Neill became the most widely translated and produced dramatist.

Period of the major works of Eugene O'Neill

O’Neill’s capacity for and commitment to work were staggering. Between 1920 and 1943 he completed 20 long plays—several of them double and triple length—and a number of shorter ones. He wrote and rewrote many of his manuscripts half a dozen times before he was satisfied, and he filled shelves of notebooks with research notes, outlines, play ideas, and other memoranda. His most-distinguished short plays include the four early sea plays, ‘Bound East for Cardiff’, ‘In the Zone’, ‘The Long Voyage Home’, and ‘The Moon of the Caribbees’, which were written between 1913 and 1917 and produced in 1924 under the overall title ‘S.S. Glencairn; The Emperor Jones’ (about the disintegration of a Pullman porter turned tropical-island dictator); and ‘The Hairy Ape’ (about the disintegration of a displaced steamship coal stoker).

O’Neill’s plays were written from an intensely personal point of view, deriving directly from the scarring effects of his family’s tragic relationships—his mother and father, who loved and tormented each other; his older brother, who loved and corrupted him and died of alcoholism in middle age; and O’Neill himself, caught and torn between love for and rage at all three.

Among his most-celebrated long plays is ‘Anna Christie’, perhaps the classic American example of the ancient “harlot with a heart of gold” theme; it became an instant popular success. O’Neill’s serious, almost solemn treatment of the struggle of a poor Swedish American girl to live down her early, enforced life of prostitution and to find happiness with a likable but unimaginative young sailor is his least-complicated tragedy. He himself disliked it from the moment he finished it, for, in his words, it had been “too easy.”

The first full-length play in which O’Neill successfully evoked the starkness and inevitability of Greek tragedy that he felt in his own life was ‘Desire Under the Elms’ (1924). Drawing on Greek themes of incest, infanticide, and fateful retribution, he framed his story in the context of his own family’s conflicts. This story of a lustful father, a weak son, and an adulterous wife who kills her infant son was told with a fine disregard for the conventions of the contemporary Broadway theatre. Because of the sparseness of its style, its avoidance of melodrama, and its total honesty of emotion, the play was acclaimed immediately as a powerful tragedy and has continued to rank among the great American plays of the 20th century.

In ‘The Great God Brown’, O’Neill dealt with a major theme that he expressed more effectively in later plays—the conflict between idealism and materialism. Although the play was too metaphysically intricate to be staged successfully when it was first produced, in 1926, it was significant for its symbolic use of masks and for the experimentation with expressionistic dialogue and action—devices that since have become commonly accepted both on the stage and in motion pictures. In spite of its confusing structure, the play is rich in symbolism and poetry, as well as in daring technique, and it became a forerunner of avant-garde movements in American theatre.

O’Neill’s innovative writing continued with ‘Strange Interlude’. This play was revolutionary in style and length: when first produced, it opened in late afternoon, broke for a dinner intermission, and ended at the conventional hour. Techniques new to the modern theatre included spoken asides or soliloquies to express the characters’ hidden thoughts. The play is the saga of Everywoman, who ritualistically acts out her roles as daughter, wife, mistress, mother, and platonic friend. Although it was innovative and startling in 1928, its obvious Freudian overtones have rapidly dated the work.

One of O’Neill’s enduring masterpieces, ‘Mourning Becomes Electra’ (1931), represents the playwright’s most complete use of Greek forms, themes, and characters. Based on the ‘Oresteia’ trilogy by Aeschylus, it was itself three plays in one. Following a long succession of tragic visions, O’Neill’s only comedy, ‘Ah, Wilderness!’, appeared on Broadway in 1933. Written in a lighthearted, nostalgic mood, the work was inspired in part by the playwright’s mischievous desire to demonstrate that he could portray the comic as well as the tragic side of life. Significantly, the play is set in the same place and period, a small New England town in the early 1900s, as his later tragic masterpiece, ‘Long Day’s Journey into Night’. Dealing with the growing pains of a sensitive, adolescent boy, ‘Ah, Wilderness!’ was characterized by O’Neill as “the other side of the coin,” meaning that it represented his fantasy of what his own youth might have been, rather than what he believed it to have been (as dramatized later in ‘Long Day’s Journey into Night’).

‘The Iceman Cometh’, the most complex and perhaps the finest of the O’Neill tragedies, followed in 1939, although it did not appear on Broadway until 1946. Laced with subtle religious symbolism, the play is a study of man’s need to cling to his hope for a better life, even if he must delude himself to do so.

Even in his last writings, O’Neill’s youth continued to absorb his attention. The posthumous production of ‘Long Day’s Journey into Night’ brought to light an agonizingly autobiographical play, one of O’Neill’s greatest. It is straightforward in style but shattering in its depiction of the agonized relations between father, mother, and two sons. Spanning one day in the life of a family, the play strips away layer after layer from each of the four central figures, revealing the mother as a defeated drug addict, the father as a man frustrated in his career and failed as a husband and father, the older son as a bitter alcoholic, and the younger son as a tubercular, disillusioned youth with only the slenderest chance for physical and spiritual survival.

O’Neill’s tragic view of life was perpetuated in his relationships with the three women he married—two of whom he divorced—and with his three children. His daughter, Oona (also by Agnes Boulton), was cut out of his life when, at 18, she infuriated him by marrying Charlie Chaplin, who was O’Neill’s age.

Until some years after his death in 1953, O’Neill, although respected in the United States, was more highly regarded abroad. Sweden, in particular, always held him in high esteem, partly because of his publicly acknowledged debt to the influence of the Swedish playwright August Strindberg, whose tragic themes often echo in O’Neill’s plays. In 1936 the Swedish Academy gave O’Neill the Nobel Prize for Literature, the first time the award had been conferred on an American playwright.

O’Neill’s most ambitious project for the theatre was one that he never completed. In the late 1930s he conceived of a cycle of 11 plays, to be performed on 11 consecutive nights, tracing the lives of an American family from the early 1800s to modern times. He wrote scenarios and outlines for several of the plays and drafts of others but completed only one in the cycle—‘A Touch of the Poet’—before a crippling illness ended his ability to hold a pencil. An unfinished rough draft of another of the cycle plays, ‘More Stately Mansions’, was published in 1964 and produced three years later on Broadway, in spite of written instructions left by O’Neill that the incomplete manuscript be destroyed after his death.

O’Neill’s final years were spent in grim frustration. Unable to work, he longed for his death and sat waiting for it in a Boston hotel, seeing no one except his doctor, a nurse, and his third wife, Carlotta Monterey. O’Neill died as broken and tragic a figure as any he had created for the stage.

Legacy of Eugene O'Neill

O’Neill was the first American dramatist to regard the stage as a literary medium and the only American playwright ever to receive the Nobel Prize for Literature. Through his efforts, the American theatre grew up during the 1920s, developing into a cultural medium that could take its place with the best in American fiction, painting, and music. Until his ‘Beyond the Horizon’ was produced, in 1920, Broadway theatrical fare, apart from musicals and an occasional European import of quality, had consisted largely of contrived melodrama and farce. O’Neill saw the theatre as a valid forum for the presentation of serious ideas. Imbued with the tragic sense of life, he aimed for a contemporary drama that had its roots in the most powerful of ancient Greek tragedies—a drama that could rise to the emotional heights of Shakespeare. For more than 20 years, both with such masterpieces as ‘Desire Under the Elms’, ‘Mourning Becomes Electra’, and ‘The Iceman Cometh’ and by his inspiration to other serious dramatists, O’Neill set the pace for the blossoming of the Broadway theatre.

It appears to me that if one wants to make progress in mathematics, one should study the masters and not the pupils. - Niels Henrik Abel.

Nothing is better than reading and gaining more and more knowledge - Stephen William Hawking.

Offline

#932 2021-07-03 00:06:45

- Jai Ganesh

- Administrator

- Registered: 2005-06-28

- Posts: 53,161

Re: crème de la crème

898) Roger Martin du Gard

Roger Martin du Gard, (born March 23, 1881, Neuilly-sur-Seine, France—died Aug. 22, 1958, Bellême), French author and winner of the 1937 Nobel Prize for Literature. Trained as a paleographer and archivist, Martin du Gard brought to his works a spirit of objectivity and a scrupulous regard for details. For his concern with documentation and with the relationship of social reality to individual development, he has been linked with the realist and naturalist traditions of the 19th century.

Martin du Gard first attracted attention with ‘Jean Barois’ (1913), which traced the development of an intellectual torn between the Roman Catholic faith of his childhood and the scientific materialism of his maturity; it also described the full impact of the Dreyfus affair on French minds. He is best known for the eight-part novel cycle ‘Les Thibault’ (1922–40; parts 1–6 as ‘The Thibaults’; parts 7–8 as ‘Summer 1914’). This record of a family’s development chronicles the social and moral issues confronting the French bourgeoisie from the turn of the 19th century to World War I. Reacting against a bourgeois patriarch, the younger son, Jacques, renounces his Roman Catholic past to embrace revolutionary socialism, and the elder son, Antoine, accepts his middle-class heritage but loses faith in its religious foundation. Both sons eventually die in World War I. The outstanding features of ‘Les Thibaults’ are the wide range of human relationships patiently explored, the graphic realism of the sickbed and death scenes, and, in the seventh volume, ‘L’Été 1914’ (“Summer 1914”), the dramatic description of Europe’s nations being swept into war.

Other works by Martin du Gard include ‘Vielle France’ (1933; ‘The Postman’), biting sketches of French country life, and ‘Notes sur André Gide’ (1951; ‘Recollections of André Gide’), a candid study of the author, who was his friend. In 1941 he began work on ‘Le Journal du colonel de Maumort’, a vast novel that he hoped would prove to be his masterpiece, but it was still unfinished at his death.

It appears to me that if one wants to make progress in mathematics, one should study the masters and not the pupils. - Niels Henrik Abel.

Nothing is better than reading and gaining more and more knowledge - Stephen William Hawking.

Offline

#933 2021-07-05 00:12:11

- Jai Ganesh

- Administrator

- Registered: 2005-06-28

- Posts: 53,161

Re: crème de la crème

899) Pearl S. Buck

Pearl S. Buck, née Pearl Comfort Sydenstricker, pseudonym John Sedges, (born June 26, 1892, Hillsboro, West Virginia, U.S.—died March 6, 1973, Danby, Vermont), American author noted for her novels of life in China. She received the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1938.

Pearl Sydenstricker was raised in Zhenjiang in eastern China by her Presbyterian missionary parents. Initially educated by her mother and a Chinese tutor, she was sent at 15 to a boarding school in Shanghai. Two years later she entered Randolph-Macon Woman’s College in Lynchburg, Virginia; she graduated in 1914 and remained for a semester as an instructor in psychology.

In May 1917 she married missionary John L. Buck; although later divorced and remarried, she retained the name Buck professionally. She returned to China and taught English literature in Chinese universities in 1925–30. During that time she briefly resumed studying in the United States at Cornell University, where she took an M.A. in 1926. She began contributing articles on Chinese life to American magazines in 1922. Her first published novel, ‘East Wind, West Wind’ (1930), was written aboard a ship headed for America.

‘The Good Earth’ (1931), a poignant tale of a Chinese peasant and his slave-wife and their struggle upward, was a best seller. The book, which won a Pulitzer Prize (1932), established Buck as an interpreter of the East to the West and was adapted for stage and screen. ‘The Good Earth’, widely translated, was followed by ‘Sons’ (1932) and ‘A House Divided’ (1935); the trilogy was published as ‘The House of Earth’ (1935). Buck was awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1938.

From 1935 Buck lived in the United States. She and her second husband, Richard Walsh, adopted six children through the years. Indeed, adoption became a personal crusade for Buck. In 1949, in a move to aid the mixed-race children fathered in Asia by U.S. servicemen, she and others established an adoption agency, Welcome House. She also founded another child-sponsorship agency, the Pearl S. Buck Foundation (1964; later renamed Opportunity House), to which in 1967 she turned over most of her earnings—more than $7 million. Welcome House and Opportunity House merged in 1991 to form Pearl S. Buck International, headquartered on Buck’s estate, Green Hills Farm in Pennsylvania, which is a national historic landmark.

After Buck’s return to the United States, she turned to biography, writing lives of her father, Absalom Sydenstricker (‘Fighting Angel’, 1936), and her mother, Caroline (‘The Exile’, 1936). Later novels include ‘Dragon Seed’ (1942) and ‘Imperial Woman’ (1956). She also published short stories, such as ‘The First Wife and Other Stories’ (1933), ‘Far and Near’ (1947), and ‘The Good Deed’ (1969); a nonfictional work, ‘The Child Who Never Grew’ (1950), about her mentally disabled daughter, Carol (1920–92); an autobiography, ‘My Several Worlds’ (1954); and a number of children’s books. Under the name John Sedges she published five novels unlike her others, including a best seller, ‘The Townsman’ (1945). In December 2012 an unpublished manuscript completed just prior to Buck’s death was discovered in a storage locker in Texas, and it was published the next year. The novel, titled ‘The Eternal Wonder’, chronicles the peregrinations of a young genius.

It appears to me that if one wants to make progress in mathematics, one should study the masters and not the pupils. - Niels Henrik Abel.

Nothing is better than reading and gaining more and more knowledge - Stephen William Hawking.

Offline

#934 2021-07-06 00:11:47

- Jai Ganesh

- Administrator

- Registered: 2005-06-28

- Posts: 53,161

Re: crème de la crème

900) Frans Eemil Sillanpää

Frans Eemil Sillanpää, (born Sept. 16, 1888, Hämeenkyrö, Finland, Russian Empire—died June 3, 1964, Helsinki, Fin.), first Finnish writer to win the Nobel Prize for Literature (1939).

The son of a peasant farmer, Sillanpää began studying natural science but in 1913 returned to the country, married, and began to write. His first short stories were published in journals in 1915. From 1924 to 1927 he worked for a publishing company in Porvoo. A new creative period followed in the early 1930s, when he wrote several of his best works.

Sillanpää’s first novel, ‘Elämä ja aurinko’ (1916; “Life and the Sun”), the story of a young man who returns home in midsummer and falls in love, is characteristic. People are seen as essentially part of nature. Instinct, through which life’s hidden purpose is revealed, rules human actions.

Shocked by the Finnish civil war of 1918, Sillanpää wrote his most substantial novel, ‘Hurskas kurjuus’ (1919; ‘Meek Heritage’), describing how a humble cottager becomes involved with the Red Guards without clearly realizing the ideological implications. The novelette Hiltu ja Ragnar (1923) is the tragic love story of a city boy and a country servant-girl. After several collections of short stories in the late 1920s, Sillanpää published his best-known, though not his most perfect, work, ‘Nuorena nukkunut’ (1931; ‘Fallen Asleep While Young’, or ‘The Maid Silja’), a story of an old peasant family. Realistic and lyric elements are blended in ‘Miehen tie’ (1932; ‘Way of a Man’), which describes a young farmer’s growth to maturity. ‘Ihmiset suviyössä’ (1934; ‘People in the Summer Night’) is stylistically his most finished and poetic novel. His reminiscences, ‘Poika eli elämäänsa’ (1953; “Telling and Describing”) and ‘Päivä korkeimmillaan’ (1956; “The High Moment of the Day”), throw new light on him as a writer.

It appears to me that if one wants to make progress in mathematics, one should study the masters and not the pupils. - Niels Henrik Abel.

Nothing is better than reading and gaining more and more knowledge - Stephen William Hawking.

Offline

#935 2021-07-08 00:04:03

- Jai Ganesh

- Administrator

- Registered: 2005-06-28

- Posts: 53,161

Re: crème de la crème

901) Johannes V. Jensen

Johannes V. Jensen, in full Johannes Vilhelm Jensen, (born Jan. 20, 1873, Farsø, Den.—died Nov. 25, 1950, Copenhagen), Danish novelist, poet, essayist, and writer of many myths, whose attempt, in his later years, to depict man’s development in the light of an idealized Darwinian theory caused his work to be much debated. He received the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1944.

Of old peasant stock and the son of a veterinarian, Jensen went to Copenhagen to study medicine but turned to writing. He first made an impression as a writer of tales. These works fall into three groups: tales from the Himmerland, tales from Jensen’s travels in the Far East (for which he was called Denmark’s Kipling), and more than 100 tales published under the recurrent title Myter (“Myths”). His early writings also include a historical trilogy, Kongens Fald (1900–01; The Fall of the King, 1933), a fictional biography of King Christian II of Denmark. Shortly thereafter, as a result of his travels in the United States, came his Madame d’Ora (1904) and Hjulet (1905; “The Wheel”). In 1906 he published a volume of poems, and late in life he returned to poetry, his Digte, 1901–43 being the result.

Jensen then worked on the six novels that are his best known work; they bear the common title Den lange rejse, 6 vol. (1908–22; The Long Journey, 3 vol., 1922–24). This story of the rise of man from the most primitive times to the discovery of America by Columbus exhibits both his imagination and his skill as an amateur anthropologist.

It appears to me that if one wants to make progress in mathematics, one should study the masters and not the pupils. - Niels Henrik Abel.

Nothing is better than reading and gaining more and more knowledge - Stephen William Hawking.

Offline

#936 2021-07-09 00:06:25

- Jai Ganesh

- Administrator

- Registered: 2005-06-28

- Posts: 53,161

Re: crème de la crème

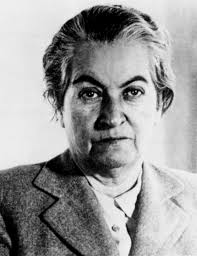

902) Gabriela Mistral

Gabriela Mistral, pseudonym of Lucila Godoy Alcayaga, (born April 7, 1889, Vicuña, Chile—died January 10, 1957, Hempstead, New York, U.S.), Chilean poet, who in 1945 became the first Latin American to win the Nobel Prize for Literature.

Of Spanish, Basque, and Indian descent, Mistral grew up in a village of northern Chile and became a schoolteacher at age 15, advancing later to the rank of college professor. Throughout her life she combined writing with a career as an educator, cultural minister, and diplomat; her diplomatic assignments included posts in Madrid, Lisbon, Genoa, and Nice.

Her reputation as a poet was established in 1914 when she won a Chilean prize for three “Sonetos de la muerte” (“Sonnets of Death”). They were signed with the name by which she has since been known, which she coined from those of two of her favourite poets, Gabriele D’Annunzio and Frédéric Mistral. A collection of her early works, 'Desolación' (1922; “Desolation”), includes the poem “Dolor,” detailing the aftermath of a love affair that was ended by the suicide of her lover. Because of this tragedy, she never married, and a haunting, wistful strain of thwarted maternal tenderness informs her work. 'Ternura' (1924, enlarged 1945; “Tenderness”), 'Tala' (1938; “Destruction”), and 'Lagar' (1954; “The Wine Press”) evidence a broader interest in humanity, but love of children and of the downtrodden remained her principal themes.

Mistral’s extraordinarily passionate verse, which is frequently coloured by figures and words peculiarly her own, is marked by warmth of feeling and emotional power. Selections of her poetry have been translated into English by the American writer Langston Hughes (1957; reissued 1972), by Mistral’s secretary and companion Doris Dana (1957; reissued 1971), by American writer Ursula K. Le Guin (2003), and by Paul Burns and Salvador Ortiz-Carboneres (2005). 'A Gabriela Mistral Reader' (1993; reissued in 1997) was translated by Maria Giachetti and edited by Marjorie Agosín. 'Selected Prose and Prose-Poems' (2002) was translated by Stephen Tapscott.

It appears to me that if one wants to make progress in mathematics, one should study the masters and not the pupils. - Niels Henrik Abel.

Nothing is better than reading and gaining more and more knowledge - Stephen William Hawking.

Offline

#937 2021-07-11 00:13:08

- Jai Ganesh

- Administrator

- Registered: 2005-06-28

- Posts: 53,161

Re: crème de la crème

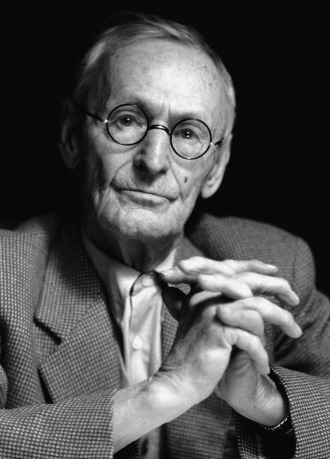

903) Hermann Hesse

Hermann Hesse, (born July 2, 1877, Calw, Germany—died August 9, 1962, Montagnola, Switzerland), German novelist and poet who was awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1946. The main theme of his work is the individual’s efforts to break out of the established modes of civilization so as to find an essential spirit and identity.

Hesse grew up in Calw and in Basel. He attended school briefly in Göppingen before, at the behest of his father, he entered the Maulbronn seminary in 1891. Though a model student, he was unable to adapt and left less than a year later. As he would later explain ,

I was a good learner, good at Latin though only fair at Greek, but I was not a very manageable boy, and it was only with difficulty that I fitted into the framework of a pietist education that aimed at subduing and breaking the individual personality.

Hesse, who aspired to be a poet, was apprenticed in a Calw tower-clock factory and later in a Tübingen bookstore. He would express his disgust with conventional schooling in the novel Unterm Rad (1906; Beneath the Wheel), in which an overly diligent student is driven to self-destruction.

Hesse published his first book, a collection of poems, in 1899. He remained in the bookselling business until 1904, when he became a freelance writer and brought out his first novel, Peter Camenzind, about a failed and dissipated writer. The novel was a success, and Hesse returned to the theme of an artist’s inward and outward search in Gertrud (1910) and Rosshalde (1914). A visit to India in these years was later reflected in Siddhartha (1922), a poetic novel, set in India at the time of the Buddha, about the search for enlightenment.

During World War I, Hesse lived in neutral Switzerland, wrote denunciations of militarism and nationalism, and edited a journal for German war prisoners and internees. He became a permanent resident of Switzerland in 1919 and a citizen in 1923, settling in Montagnola.

A deepening sense of personal crisis led Hesse to psychoanalysis with J.B. Lang, a disciple of Carl Jung. The influence of analysis appears in Demian (1919), an examination of the achievement of self-awareness by a troubled adolescent. This novel had a pervasive effect on a troubled Germany and made its author famous. Hesse’s later work shows his interest in Jungian concepts of introversion and extraversion, the collective unconscious, idealism, and symbols. Hesse also came to be preoccupied with what he saw as the duality of human nature.

Der Steppenwolf (1927; Steppenwolf ) describes the conflict between bourgeois acceptance and spiritual self-realization in a middle-aged man. In Narziss und Goldmund (1930; Narcissus and Goldmund), an intellectual ascetic who is content with established religious faith is contrasted with an artistic sensualist pursuing his own form of salvation. Hesse’s last and longest novel, Das Glasperlenspiel (1943; English titles The Glass Bead Game and Magister Ludi), is set in the 23rd century. In it Hesse again explores the dualism of the contemplative and the active life, this time through the figure of a supremely gifted intellectual. He subsequently published letters, essays, and stories.

After World War II, Hesse’s popularity among German readers soared, though it had crashed by the 1950s. His appeal for self-realization and his celebration of Eastern mysticism transformed him into something of a cult figure to young people in the English-speaking world in the 1960s and ’70s, and this vein of his work ensured an international audience for his work afterward.

It appears to me that if one wants to make progress in mathematics, one should study the masters and not the pupils. - Niels Henrik Abel.

Nothing is better than reading and gaining more and more knowledge - Stephen William Hawking.

Offline

#938 2021-07-13 00:08:52

- Jai Ganesh

- Administrator

- Registered: 2005-06-28

- Posts: 53,161

Re: crème de la crème

904) André Gide

André Gide, in full André-Paul-Guillaume Gide, (born Nov. 22, 1869, Paris, France—died Feb. 19, 1951, Paris), French writer, humanist, and moralist who received the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1947.

Heritage and youth

Gide was the only child of Paul Gide and his wife, Juliette Rondeaux. His father was of southern Huguenot peasant stock; his mother, a Norman heiress, although Protestant by upbringing, belonged to a northern Roman Catholic family long established at Rouen. When Gide was eight he was sent to the École Alsacienne in Paris, but his education was much interrupted by neurotic bouts of ill health. After his father’s early death in 1880, his well-being became the chief concern of his devoutly austere mother; often kept at home, he was taught by indifferent tutors and by his mother’s governess. While in Rouen Gide formed a deep attachment for his cousin, Madeleine Rondeaux.

Gide returned to the École Alsacienne to prepare for his ‘baccalauréat’ examination, and after passing it in 1889, he decided to spend his life in writing, music, and travel. His first work was an autobiographical study of youthful unrest entitled ‘Les Cahiers d’André Walter’ (1891; ‘The Notebooks of André Walter’). Written, like most of his later works, in the first person, it uses the confessional form in which Gide was to achieve his greatest successes.

Symbolist period

In 1891 a school friend, the writer Pierre Louÿs, introduced Gide into the poet Stéphane Mallarmé’s famous “Tuesday evenings,” which were the centre of the French Symbolist movement, and for a time Gide was influenced by Symbolist aesthetic theories. His works “Narcissus” (1891), ‘Le Voyage d’Urien’ (1893; ‘Urien’s Voyage’), and “The Lovers’ Attempt” (1893) belong to this period.

In 1893 Gide paid his first visit to North Africa, hoping to find release there from his dissatisfaction with the restrictions imposed by his puritanically strict Protestant upbringing. Gide’s contact with the Arab world and its radically different moral standards helped to liberate him from the Victorian social and sexual conventions he felt stifled by. One result of this nascent intellectual revolt against social hypocrisy was his growing awareness of his homosexuality. The lyrical prose poem ‘Les Nourritures terrestres’ (1897; ‘Fruits of the Earth’) reflects Gide’s personal liberation from the fear of sin and his acceptance of the need to follow his own impulses. But after he returned to France, Gide’s relief at having shed the shackles of convention evaporated in what he called the “stifling atmosphere” of the Paris salons. He satirized his surroundings in Marshlands (1894), a brilliant parable of animals who, living always in dark caves, lose their sight because they never use it.

In 1894 Gide returned to North Africa, where he met Oscar Wilde and Lord Alfred Douglas, who encouraged him to embrace his homosexuality. He was recalled to France because of his mother’s illness, however, and she died in May 1895.

In October 1895 Gide married his cousin Madeleine, who had earlier refused him. Early in 1896 he was elected mayor of the commune of La Roque. At 27, he was the youngest mayor in France. He took his duties seriously but managed to complete ‘Fruits of the Earth’. It was published in 1897 and fell completely flat, although after World War I it was to become Gide’s most popular and influential work. In the postwar generation, its call to each individual to express fully whatever is in him evoked an immediate response.

Great creative period

‘Le Prométhée mal enchaîné’ (1899; ‘Prometheus Misbound’), a return to the satirical style of ‘Urien’s Voyage’ and ‘Marshland’, is Gide’s last discussion of man’s search for individual values. His next tales mark the beginning of his great creative period. ‘L’Immoraliste’ (1902; ‘The Immoralist’), ‘La Porte étroite’ (1909; ‘Strait Is the Gate’), and ‘La Symphonie pastorale’ (1919; “The Pastoral Symphony”) reflect Gide’s attempts to achieve harmony in his marriage in their treatment of the problems of human relationships. They mark an important stage in his development: adapting his works’ treatment and style to his concern with psychological problems. ‘The Immoralist and ‘Strait Is the Gate’ are in the prose form which Gide termed a ‘récit’; i.e., a studiedly simple but deeply ironic tale in which a first-person narrator reveals the inherent moral ambiguities of life by means of his seemingly innocuous reminiscences. In these works Gide achieves a mastery of classical construction and a pure, simple style.

During most of this period Gide was suffering deep anxiety and distress. Although his love for Madeleine had given his life what he called its “mystic orientation,” he found himself unable, in a close, permanent relationship, to reconcile this love with his need for freedom and for experience of every kind. ‘Les Caves du Vatican’ (1914; ‘The Vatican Swindle’) marks the transition to the second phase of Gide’s great creative period. He called it not a tale but a sotie, by which he meant a satirical work whose foolish or mad characters are treated farcically within an unconventional narrative structure. This was the first of his works to be violently attacked for anticlericalism.

In the early 1900s Gide had already begun to be widely known as a literary critic, and in 1908 he was foremost among those who founded ‘La Nouvelle Revue Française’, the literary review that was to unite progressive French writers until World War II. During World War I Gide worked in Paris, first for the Red Cross, then in a soldiers’ convalescent home, and finally in providing shelter to war refugees. In 1916 he returned to Cuverville, his home since his marriage, and began to write again.

The war had intensified Gide’s anguish, and early in 1916 he had begun to keep a second ‘Journal’ (published in 1926 as ‘Numquid et tu?’) in which he recorded his search for God. Finally, however, unable to resolve the dilemma (expressed in his statement “Catholicism is inadmissible, Protestantism is intolerable; and I feel profoundly Christian”), he resolved to achieve his own ethic, and by casting off his sense of guilt to become his true self. Now, in a desire to liquidate the past, he began his autobiography, ‘Si le grain ne meurt’ (1926; ‘If It Die . . ‘), an account of his life from birth to marriage that is among the great works of confessional literature. In 1918 his friendship for the young Marc Allégret caused a serious crisis in his marriage, when his wife in jealous despair destroyed her “dearest possession on earth”—his letters to her.

After the war a great change took place in Gide, and his face began to assume the serene expression of his later years. Gide called his next work, ‘Les Faux-Monnayeurs’ (1926; ‘The Counterfeiters’), his only novel. He meant by this that in conception, range, and scope it was on a vaster scale than his tales or his ‘soties’. It is the most complex and intricately constructed of his works, dealing as it does with the relatives and teachers of a group of schoolboys subject to corrupting influences both in and out of the classroom. ‘The Counterfeiters’ treats all of Gide’s favourite themes in a progression of discontinuous scenes and happenings that come close to approximating the texture of daily life itself.

In 1925 Gide set off for French Equatorial Africa. When he returned he published ‘Voyage au Congo’ (1927; ‘Travels in the Congo’), in which he criticized French colonial policies. The compassionate, objective concern for humanity that marks the final phase of Gide’s life found expression in political activities at this time. He became the champion of society’s victims and outcasts, demanding more humane conditions for criminals and equality for women. For a time it seemed to him that he had found a faith in Communism. In 1936 he set out on a visit to the Soviet Union, but later expressed his disillusionment with the Soviet system in ‘Retour de l’U.R.S.S.’ (1936; ‘Return from the U.S.S.R.’) and ‘Retouches à mon retour de l’U.R.S.S.’ (1937; ‘Afterthoughts on the U.S.S.R.’).

Late works of André Gide

In 1938 Gide’s wife, Madeleine, died. After a long estrangement they had been brought together by her final illness. To him she was always the great—perhaps the only—love of his life. With the outbreak of World War II, Gide began to realize the value of tradition and to appreciate the past. In a series of imaginary interviews written in 1941 and 1942 for ‘Le Figaro’, he expressed a new concept of liberty, declaring that absolute freedom destroys both the individual and society: freedom must be linked with the discipline of tradition. From 1942 until the end of the war Gide lived in North Africa. There he wrote “Theseus,” whose story symbolizes Gide’s realization of the value of the past: Theseus returns to Ariadne only because he has clung to the thread of tradition.

In June 1947 Gide received the first honour of his life: the Doctor of Letters of the University of Oxford. It was followed in November by the Nobel Prize for Literature. In 1950 he published the last volume of his Journal, which took the record of his life up to his 80th birthday. All Gide’s writings illuminate some aspect of his complex character. He is seen at his most characteristic, however, in the Journal he kept from 1889, a unique work of more than a million words in which he records his experiences, impressions, interests, and moral crises during a period of more than 60 years. After its publication he resolved to write no more.

Gide’s lifelong emphasis on the self-aware and sincere individual as the touchstone of both collective and individual morality was complemented by the tolerant and enlightened views he expressed on literary, social, and political questions throughout his career. For most of his life a controversial figure, Gide was long regarded as a revolutionary for his open support of the claims of the individual’s freedom of action in defiance of conventional morality. Before his death he was widely recognized as an important humanist and moralist in the great 17th-century French tradition. The integrity and nobility of his thought and the purity and harmony of style that characterize his stories, verse, and autobiographical works have ensured his place among the masters of French literature.

It appears to me that if one wants to make progress in mathematics, one should study the masters and not the pupils. - Niels Henrik Abel.

Nothing is better than reading and gaining more and more knowledge - Stephen William Hawking.

Offline

#939 2021-07-15 00:04:59

- Jai Ganesh

- Administrator

- Registered: 2005-06-28

- Posts: 53,161

Re: crème de la crème

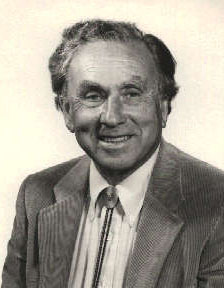

905) Robert Hofstadter

Robert Hofstadter, (born February 5, 1915, New York, New York, U.S.—died November 17, 1990, Stanford, California), American scientist who was a joint recipient of the Nobel Prize for Physics in 1961 for his investigations of protons and neutrons, which revealed the hitherto unknown structure of these particles. He shared the prize with Rudolf Ludwig Mössbauer of Germany.

Hofstadter was educated at Princeton University, where he earned a Ph.D. in 1938. As a physicist at the National Bureau of Standards during World War II, he was instrumental in developing the proximity fuse, which was used to detonate antiaircraft and other artillery shells. He joined the faculty of Princeton in 1946, where his principal scientific work dealt with the study of infrared rays, photoconductivity, and crystal and scintillation counters.

Hofstadter taught at Stanford University from 1950 to 1985. At Stanford he used a linear electron accelerator to measure and explore the constituents of atomic nuclei. At the time, protons, neutrons, and electrons were all thought to be structureless particles; Hofstadter discovered that protons and neutrons have a definite size and form. He was able to determine the precise size of the proton and neutron and provide the first reasonably consistent picture of the structure of the atomic nucleus. Hofstadter found that both the proton and neutron have a central, positively charged core surrounded by a double cloud of pi-mesons. Both clouds are positively charged in the proton, but in the neutron the inner cloud is negatively charged, thus giving a net zero charge for the entire particle.

It appears to me that if one wants to make progress in mathematics, one should study the masters and not the pupils. - Niels Henrik Abel.

Nothing is better than reading and gaining more and more knowledge - Stephen William Hawking.

Offline

#940 2021-07-17 00:11:03

- Jai Ganesh

- Administrator

- Registered: 2005-06-28

- Posts: 53,161

Re: crème de la crème

906) Rudolf Ludwig Mössbauer

Rudolf Ludwig Mössbauer, (born January 31, 1929, Munich, Germany—died September 14, 2011, Grünwald), German physicist and winner, with Robert Hofstadter of the United States, of the Nobel Prize for Physics in 1961 for his discovery of the Mössbauer effect.

Mössbauer discovered the effect in 1957, one year before he received his doctorate from the Technical University in Munich. Under normal conditions, atomic nuclei recoil when they emit gamma rays, and the wavelength of the emission varies with the amount of recoil. Mössbauer found that at a low temperature a nucleus can be embedded in a crystal lattice that absorbs its recoil. The discovery of the Mössbauer effect made it possible to produce gamma rays at specific wavelengths, and this proved a useful tool because of the highly precise measurements it allowed. The sharply defined gamma rays of the Mössbauer effect have been used to verify Albert Einstein’s general theory of relativity and to measure the magnetic fields of atomic nuclei.

Mössbauer became professor of physics at the California Institute of Technology, Pasadena, in 1961. Three years later he returned to Munich to become professor of physics at the Technical University, where he retired as professor emeritus in 1997.

(Mössbauer effect, also called recoil-free gamma-ray resonance absorption, nuclear process permitting the resonance absorption of gamma rays. It is made possible by fixing atomic nuclei in the lattice of solids so that energy is not lost in recoil during the emission and absorption of radiation. The process, discovered by the German-born physicist Rudolf L. Mössbauer in 1957, constitutes a useful tool for studying diverse scientific phenomena.

In order to understand the basis of the Mössbauer effect, it is necessary to understand several fundamental principles. The first of these is the Doppler shift. When a locomotive whistles, the frequency, or pitch, of the sound waves is increased while the whistle is approaching a listener and decreased as the whistle recedes. The Doppler formula expresses this change, or shift in frequency, of the waves as a linear function of the velocity of the locomotive. Similarly, when the nucleus of an atom radiates electromagnetic energy in the form of a wave packet known as a gamma-ray photon it is also subject to the Doppler shift. The frequency change, which is perceived as an energy change, depends on how fast the nucleus is moving with respect to the observer.

The second concept, that of nuclear recoil, may be illustrated by the behaviour of a rifle. If it is held loosely during firing, its recoil, or “kick,” will be violent. If it is firmly held against the marksman’s shoulder, the recoil will be greatly reduced. The difference in the two situations results from the fact that momentum (the product of mass and velocity) is conserved: the momentum of the system that fires a projectile must be opposite and equal to that of the projectile. By supporting the rifle firmly, the marksman includes his body, with its much greater mass, as part of the firing system and the backward velocity of the system is correspondingly reduced. An atomic nucleus is subject to the same law. When radiation is emitted in the form of a gamma ray, the atom with its nucleus experiences a recoil due to the momentum of the gamma ray. A similar recoil occurs during absorption of radiation by a nucleus.

Finally, it is necessary to understand the principles governing the absorption of gamma rays by nuclei. Nuclei can exist only in certain definite energy states. For a gamma ray to be absorbed its energy must be exactly equal to the difference between two of these states. Such an absorption is called resonance absorption. A gamma ray that is ejected from a nucleus in a free atom cannot be resonantly absorbed by a similar nucleus in another atom because its energy is less than the resonance energy by an amount equal to the kinetic energy given to the recoiling source nucleus.)

It appears to me that if one wants to make progress in mathematics, one should study the masters and not the pupils. - Niels Henrik Abel.

Nothing is better than reading and gaining more and more knowledge - Stephen William Hawking.

Offline

#941 2021-07-19 00:19:32

- Jai Ganesh

- Administrator

- Registered: 2005-06-28

- Posts: 53,161

Re: crème de la crème

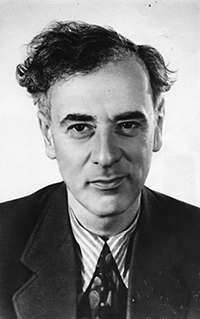

907) Lev Davidovich Landau

Lev Davidovich Landau, (born Jan. 9 [Jan. 22, New Style], 1908, Baku, Russian Empire (now Azerbaijan)—died April 1, 1968, Moscow, Russia, U.S.S.R.), Soviet theoretical physicist, one of the founders of the quantum theory of condensed matter whose pioneering research in this field was recognized with the 1962 Nobel Prize for Physics.

Landau was a mathematical prodigy and enfant terrible. His schooling reflected the zigzags of radical educational reforms during the turbulent period following the Russian Revolution of 1917. Like many scientists of the first Soviet generation, Landau did not formally complete some educational stages, such as high school. He never wrote a doctoral thesis either, as academic degrees had been abolished and were not restored until 1934. He did complete the undergraduate course in physics at Leningrad State University, where he studied from 1924 to 1927. In 1934 Landau was granted a doctorate as an already established scholar.

While still a student, Landau published his first articles. A new theory of quantum mechanics appeared in Germany during those years, and the 20-year-old complained that he had arrived a little too late to take part in the great scientific revolution. By 1927 quantum mechanics was essentially completed, and physicists started working on its relativistic generalization and applications to solid-state and nuclear physics. Landau matured professionally in Yakov I. Frenkel’s seminar at the Leningrad Physico-Technical Institute and then during his foreign trip of 1929–31. Supported by a Soviet stipend and a Rockefeller fellowship, he visited universities in Zürich, Copenhagen, and Cambridge, learning especially from physicists Wolfgang Pauli and Niels Bohr. In 1930 Landau pointed out a new effect resulting from the quantization of free electrons in crystals—the Landau diamagnetism, opposite to the spin paramagnetism earlier treated by Pauli. In a joint paper with physicist Rudolf Peierls, Landau argued for the need of yet another radical conceptual revolution in physics in order to resolve the mounting difficulties in relativistic quantum theory.

In 1932, soon after his return to the Soviet Union, Landau moved to the Ukrainian Physico-Technical Institute (UFTI) in Kharkov (now Kharkiv). Recently organized and run by a group of young physicists, UFTI burst into the new fields of nuclear, theoretical, and low-temperature physics. Together with his first students—Evgeny math, Isaak Pomeranchuk, and Aleksandr Akhiezer—Landau calculated effects in quantum electrodynamics and worked on the theory of metals, ferromagnetism, and superconductivity in close collaboration with Lev Shubnikov’s experimental cryogenics laboratory at the institute. In 1937 Landau published his theory of phase transitions of the second order, in which thermodynamic parameters of the system change continuously but its symmetry switches abruptly.

That same year, political problems caused his abrupt move to Pyotr Kapitsa’s Institute of Physical Problems in Moscow. Institutional conflicts at UFTI and Kharkov University, and Landau’s own iconoclastic behaviour, became politicized in the context of the Stalinist purge, producing a life-threatening situation. Later in 1937 several UFTI scientists were arrested by the political police and some, including Shubnikov, were executed. Surveillance followed Landau to Moscow, where he was arrested in April 1938 after discussing an anti-Stalinist leaflet with two colleagues. One year later, Kapitsa managed to get Landau released from prison by writing to the Russian prime minister, Vyacheslav M. Molotov, that he required the theoretician’s help in order to understand new phenomena observed in liquid helium.

A quantum theoretical explanation of Kapitsa’s discovery of superfluidity in liquid helium was published by Landau in 1941. Landau’s theory relied on a concept of collective excitations that had been suggested somewhat earlier by Frenkel and physicist Igor Tamm. A quantized unit of collective motion of many atomic particles, such excitation can be mathematically described as if it were a single particle of some novel kind, often called a “quasiparticle.” To explain superfluidity, Landau postulated that in addition to the phonon (the quantum of a sound wave) there exists another collective excitation, the roton (the quantum of vortex movement). Landau’s theory of superfluidity won acceptance in the 1950s after several experiments confirmed some new effects and quantitative predictions based on it.

In 1946 Landau was elected a full member of the U.S.S.R. Academy of Sciences. He organized a theoretical group in the Institute of Physical Problems with Isaak Khalatnikov and later Alexey A. Abrikosov. New students had to pass a series of challenging exams, called the Landau minimum, in order to join the group. The group’s weekly colloquium served as the major discussion centre for theoretical physics in Moscow, although many speakers could not cope with the devastating level of criticism considered normal at its meetings. Over the years, Landau and math published their multivolume ‘Course of Theoretical Physics’, a major learning tool for several generations of research students worldwide.

The collective work of Landau’s group embraced practically every branch of theoretical physics. In 1946 he described the phenomenon of Landau damping of electromagnetic waves in plasma. Together with Vitaly L. Ginzburg, in 1950 Landau obtained the correct equations of the macroscopic (phenomenological) theory of superconductivity. During the 1950s he and collaborators discovered that even in renormalized quantum electrodynamics, a new divergence difficulty appears (the Moscow zero, or the Landau pole). The phenomenon of the coupling constant becoming infinite or vanishing at some energy is an important feature of modern quantum field theories. In addition to his 1941 theory of superfluidity, in 1956–58 Landau introduced a different kind of quantum liquid, whose collective excitations behave statistically as fermions (such as electrons, neutrons, and protons) rather than bosons (such as mesons). His Fermi-liquid theory provided the basis for the modern theory of electrons in metals and also helped explain superfluidity in He-3, the lighter isotope of helium. In the works of Landau and his students, the method of quasiparticles was successfully applied to various problems and developed into an indispensable foundation of the theory of condensed matter.