Math Is Fun Forum

You are not logged in.

- Topics: Active | Unanswered

#1776 2025-09-18 21:43:55

- Jai Ganesh

- Administrator

- Registered: 2005-06-28

- Posts: 53,025

Re: crème de la crème

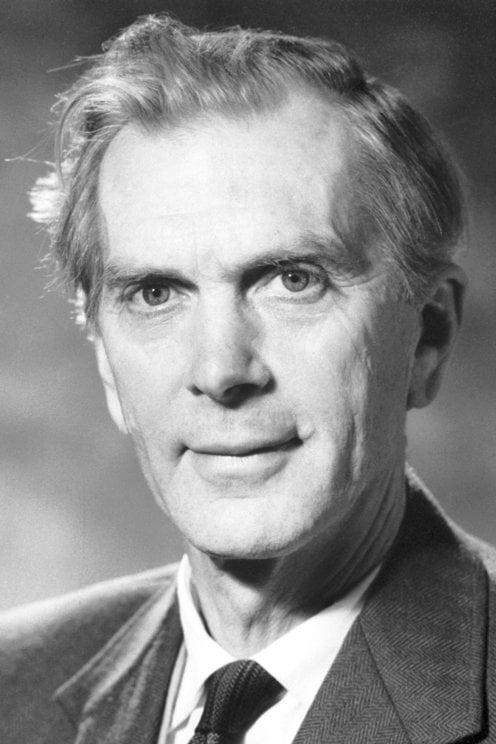

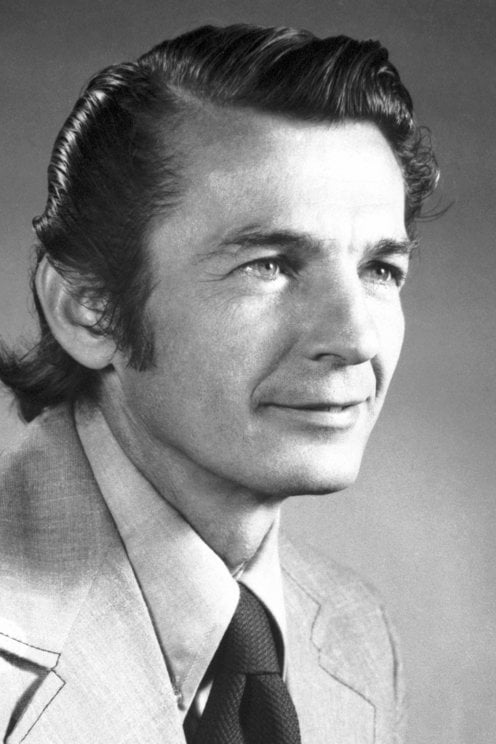

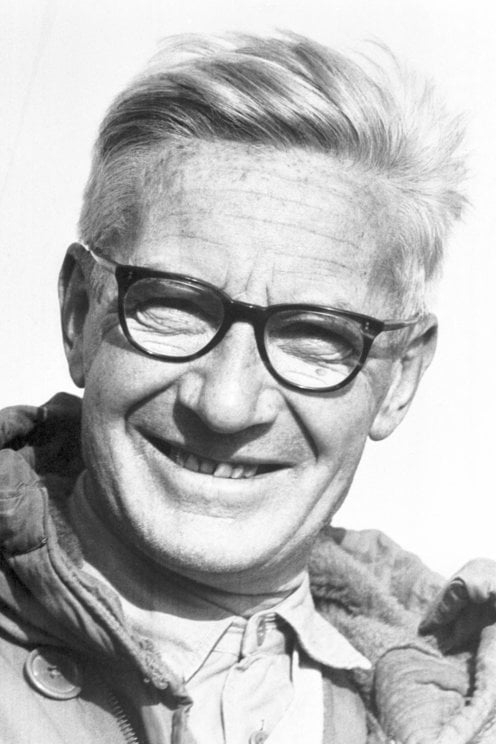

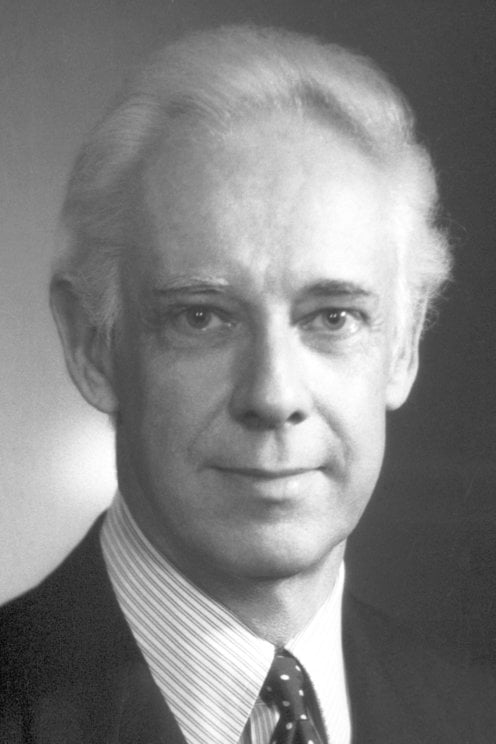

2339) Martin Ryle

Gist:

Work

Stars and other astronomical objects emit not only visible light, but also radio waves. In the 1940s Martin Ryle developed a telescope designed to capture radio waves and methods for reading and processing the data received. By connecting a number of telescopes several kilometers from one another, he created the equivalent of a telescope as large as the entire surface between the individual telescopes. This paved the way for a precise mapping of stars and galaxies and a clearer picture of the universe’s evolution.

Summary

Sir Martin Ryle (born Sept. 27, 1918, Brighton, Sussex, Eng.—died Oct. 14, 1984, Cambridge, Cambridgeshire) was a British radio astronomer who developed revolutionary radio telescope systems and used them for accurate location of weak radio sources. With improved equipment, he observed the most distant known galaxies of the universe. Ryle and Antony Hewish shared the Nobel Prize for Physics in 1974, the first Nobel prize awarded in recognition of astronomical research.

Ryle was the nephew of the philosopher Gilbert Ryle. After earning a degree in physics at the University of Oxford in 1939, he worked with the Telecommunications Research Establishment on the design of radar equipment during World War II. After the war he received a fellowship at the Cavendish Laboratory of the University of Cambridge, where he became an early investigator of extraterrestrial radio sources and developed advanced radio telescopes using the principles of radar. While serving as university lecturer in physics at Cambridge from 1948 to 1959, he became director of the Mullard Radio Astronomy Observatory (1957), and he became professor of radio astronomy in 1959. He was elected a fellow of the Royal Society in 1952, was knighted in 1966, and succeeded Sir Richard Woolley as Astronomer Royal (1972–82).

Ryle’s early work centred on studies of radio waves from the Sun, sunspots, and a few nearby stars. He guided the Cambridge radio astronomy group in the production of radio source catalogues. The Third Cambridge Catalogue (1959) helped lead to the discovery of the first quasi-stellar object (quasar).

To map such distant radio sources as quasars, Ryle developed a technique called aperture synthesis. By using two radio telescopes and changing the distance between them, he obtained data that, upon computer analysis, provided tremendously increased resolving power. In the mid-1960s Ryle put into operation two telescopes on rails that at the maximum distance of 1.6 km (1 mile) provided results comparable to a single telescope 1.6 km in diameter. This telescope system was used to locate the first pulsar, which had been discovered in 1967 by Hewish and Jocelyn Bell of the Cambridge group.

Details

Sir Martin Ryle (27 September 1918 – 14 October 1984) was an English radio astronomer who developed revolutionary radio telescope systems (see e.g. aperture synthesis) and used them for accurate location and imaging of weak radio sources. In 1946 Ryle and Derek Vonberg were the first people to publish interferometric astronomical measurements at radio wavelengths. With improved equipment, Ryle observed the most distant known galaxies in the universe at that time. He was the first Professor of Radio Astronomy in the University of Cambridge and founding director of the Mullard Radio Astronomy Observatory. He was the twelfth Astronomer Royal from 1972 to 1982. Ryle and Antony Hewish shared the Nobel Prize for Physics in 1974, the first Nobel prize awarded in recognition of astronomical research. In the 1970s, Ryle turned the greater part of his attention from astronomy to social and political issues which he considered to be more urgent. He was also an enthusiastic amateur radio operator (callsign G3CY).

Education and early life

Martin Ryle was born in Brighton, England, the son of Professor John Alfred Ryle and Miriam (née Scully) Ryle. He was the nephew of Oxford University Professor of Philosophy Gilbert Ryle. Martin had four siblings, and at first was educated at home by a governess. After studying at Bradfield College, Ryle studied physics at Christ Church, Oxford. In 1939, Ryle worked with the Telecommunications Research Establishment (TRE) on the design of antennas for airborne radar equipment during World War II. After the war, he received a fellowship at the Cavendish Laboratory.

Career and research

The focus of Ryle's early work in Cambridge was on radio waves from the Sun. His interest quickly shifted to other areas, however, and he decided early on that the Cambridge group should develop new observing techniques. As a result, Ryle was the driving force in the creation and improvement of astronomical interferometry and aperture synthesis, which paved the way for massive upgrades in the quality of radio astronomical data. In 1946 Ryle built the first multi-element astronomical radio interferometer.

Ryle guided the Cambridge radio astronomy group in the production of several important radio source catalogues. One such catalogue, the Third Cambridge Catalogue of Radio Sources (3C) in 1959 helped lead to the discovery of the first quasi-stellar object (quasar).

While serving as university lecturer in physics at Cambridge from 1948 to 1959, Ryle became director of the Mullard Radio Astronomy Observatory in 1957 and professor of radio astronomy in 1959. He was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society (FRS) in 1952, was knighted in 1966 and succeeded Sir Richard Woolley as Astronomer Royal from 1972 to 1982. Ryle and Antony Hewish shared the Nobel Prize for Physics in 1974, the first Nobel prize awarded in recognition of astronomical research. In 1968 Ryle served as professor of astronomy at Gresham College, London.

Personality

According to numerous reports Ryle was quick-thinking, impatient with those slower than himself and charismatic. He was also idealistic, a characteristic he shared with his father. In an interview in 1982 he said "At times one feels that one should almost have a car sticker saying 'Stop Science Now' because we're getting cleverer and cleverer, but we do not increase the wisdom to go with it."

He was also intense and volatile, the latter characteristic being associated with his mother.. The historian Owen Chadwick described him as "a rare personality, of exceptional sensitivity of mind, fears and anxieties, care and compassion, humour and anger."

Ryle was sometimes considered difficult to work with – he often worked in an office at the Mullard Radio Astronomy Observatory to avoid disturbances from other members of the Cavendish Laboratory and to avoid getting into heated arguments, as Ryle had a hot temper. Ryle worried that Cambridge would lose its standing in the radio astronomy community as other radio astronomy groups had much better funding, so he encouraged a certain amount of secrecy about his aperture synthesis methods in order to keep an advantage for the Cambridge group. Ryle had heated arguments with Fred Hoyle of the Institute of Astronomy about Hoyle's steady state universe, which restricted collaboration between the Cavendish Radio Astronomy Group and the Institute of Astronomy during the 1960s.

War, peace and energy

Ryle was a new physics graduate and an experienced amateur radio enthusiast in 1939, when the Second World War started. He played an important part in the Allied war effort, working mainly in radar countermeasures. After the war, "He returned to Cambridge with a determination to devote himself to pure science, unalloyed by the taint of war."

In the 1970s, Ryle turned the greater part of his attention from astronomy to social and political issues which he considered to be more urgent. With publications from 1976 and continuing, despite illness until he died in 1984, he pursued a passionate and intensive program on the socially responsible use of science and technology. His main themes were:

* Warning the world of the horrific dangers of nuclear armaments, notably in his pamphlet Towards the Nuclear Holocaust.

* Criticism of nuclear power, as in Is there a case for nuclear power?

* Research and promotion of alternative energy and energy efficiency, as in Short-term Storage and Wind Power Availability.

* Calling for the responsible use of science and technology. "...we should strive to see how the vast resources now diverted towards the destruction of life are turned instead to the solution of the problems which both rich - but especially the poor - countries of the world now face."

In 1983 Ryle responded to a request from the President of the Pontifical Academy of Sciences for suggestions of topics to be discussed at a meeting on Science and Peace. Ryle's reply was published posthumously in Martin Ryle's Letter. An abridged version appears in New Scientist with the title Martin Ryle's Last Testament. The letter ends with "Our cleverness has grown prodigiously – but not our wisdom."

It appears to me that if one wants to make progress in mathematics, one should study the masters and not the pupils. - Niels Henrik Abel.

Nothing is better than reading and gaining more and more knowledge - Stephen William Hawking.

Offline

#1777 2025-09-19 20:13:40

- Jai Ganesh

- Administrator

- Registered: 2005-06-28

- Posts: 53,025

Re: crème de la crème

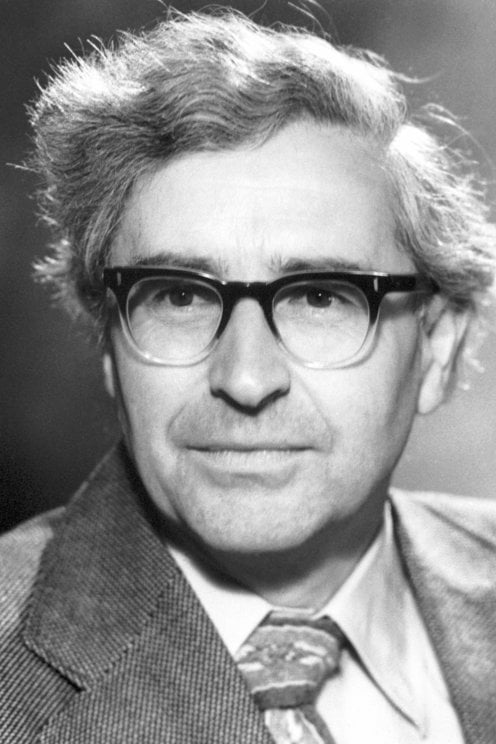

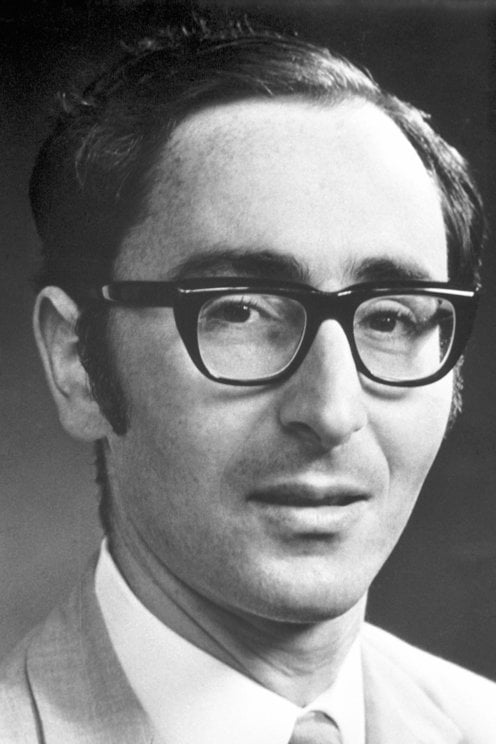

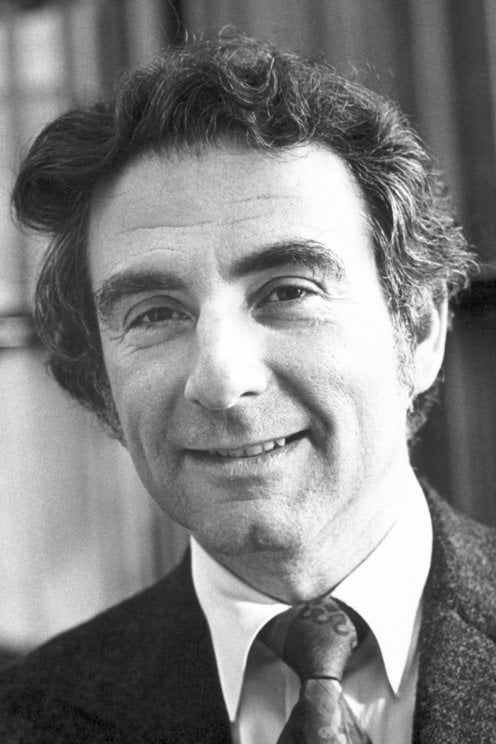

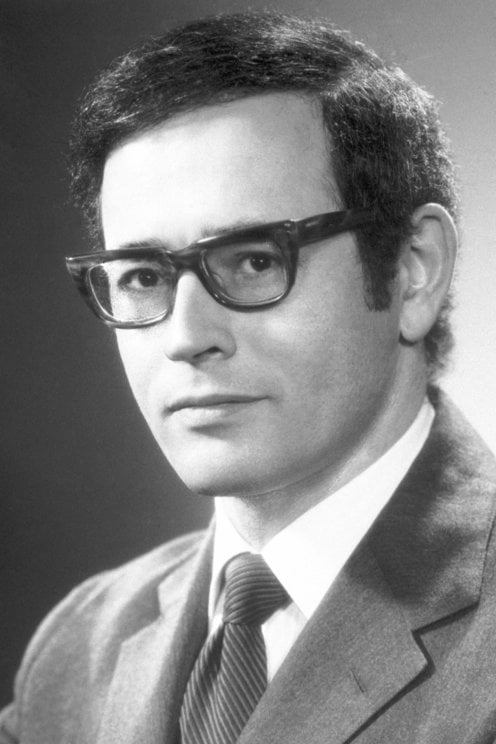

2340) Antony Hewish

Gist:

Work

Stars and other astronomical objects emit not only visible light, but also radio waves. In 1967 Antony Hewish and Jocelyn Bell discovered a previously unknown source of radiation that emitted radio waves in the form of pulses at intervals that were extremely regular. It turned out that this type of astronomical object, which became known as pulsars, has a core consisting of an extremely compact star, a neutron star. Their discovery allowed scientists to prove these stars exist.

Summary

Antony Hewish (born May 11, 1924, Fowey, Cornwall, England—died September 13, 2021) was a British astrophysicist who won the Nobel Prize for Physics in 1974 for his discovery of pulsars (cosmic objects that emit extremely regular pulses of radio waves).

Hewish was educated at the University of Cambridge and in 1946 joined the radio astronomy group there led by Sir Martin Ryle. While directing a research project at the Mullard Radio Astronomy Observatory at Cambridge in 1967, Hewish recognized the significance of an observation made by a graduate assistant, Jocelyn Bell. He determined that the regularly patterned radio signals, or pulses, that Bell had detected were not caused by earthly interference or, as some speculated, by intelligent life forms trying to communicate with distant planets but rather were energy emissions from certain stars. For this work in identifying pulsars as a new class of stars, he was awarded jointly with Ryle the Nobel Prize for Physics in 1974, the first time the prize had been given for observational astronomy.

Hewish was professor of radio astronomy at the Cavendish Laboratory, Cambridge, from 1971 to 1989.

Details

Antony Hewish (11 May 1924 – 13 September 2021) was a British radio astronomer who won the Nobel Prize for Physics in 1974 (together with fellow radio-astronomer Martin Ryle) for his role in the discovery of pulsars. He was also awarded the Eddington Medal of the Royal Astronomical Society in 1969.

Early life and education

Hewish attended King's College, Taunton. His undergraduate degree, at Gonville and Caius College, Cambridge, was interrupted by the Second World War. He was assigned to war service at the Royal Aircraft Establishment, and at the Telecommunications Research Establishment where he worked with Martin Ryle. Returning to the University of Cambridge in 1946, Hewish completed his undergraduate degree and became a postgraduate student in Ryle's research team at the Cavendish Laboratory. For his PhD thesis, awarded in 1952, Hewish made practical and theoretical advances in the observation and exploitation of the scintillations of astronomical radio sources, due to foreground plasma.

Career and research

Hewish proposed the construction of a large phased array radio telescope, which could be used to perform a survey at high time resolution, primarily for studying interplanetary scintillation. In 1965 he secured funding to construct his design, the Interplanetary Scintillation Array, at the Mullard Radio Astronomy Observatory (MRAO) outside Cambridge. It was completed in 1967. One of Hewish's PhD students, Jocelyn Bell (later known as Jocelyn Bell Burnell), helped to build the array and was assigned to analyse its output. Bell soon discovered a radio source which was ultimately recognised as the first pulsar. Hewish initially thought that the signal might be radio frequency interference, but it remained at a constant right ascension, which is unlikely for a terrestrial source. The scientific paper announcing the discovery had five authors, Hewish's name being listed first, Bell's second.

Hewish and Ryle were awarded the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1974 for work on the development of radio aperture synthesis and for Hewish's decisive role in the discovery of pulsars. The exclusion of Bell from the Nobel prize was controversial. Fellow Cambridge astronomer Fred Hoyle argued that Bell should have received a share of the prize, although Bell herself stated "it would demean Nobel Prizes if they were awarded to research students, except in very exceptional cases, and I do not believe this is one of them". Michael Rowan-Robinson later wrote that "Hewish was undoubtedly the major player in the work that led to the discovery, inventing the scintillation technique in 1952, leading the team that built the array and made the discovery, and providing the interpretation".

Hewish was professor of radio astronomy in the Cavendish Laboratory from 1971 to 1989 and head of the MRAO from 1982 to 1988. He developed an association with the Royal Institution in London when it was directed by Sir Lawrence Bragg. In 1965 he was invited to co-deliver the Royal Institution Christmas Lecture on "Exploration of the Universe". He subsequently gave several Friday Evening Discourses and was made a Professor of the Royal Institution in 1977. Hewish was a fellow of Churchill College, Cambridge. He was also a member of the Advisory Council for the Campaign for Science and Engineering.

Awards and honours

Hewish had honorary degrees from six universities, including Manchester, Exeter and Cambridge, was a foreign member of the Belgian Royal Academy, American Academy of Arts and Sciences and the Indian National Science Academy. The National Portrait Gallery holds multiple portraits of him in its permanent collection. Other awards and honours include:

* Elected a Fellow of the Royal Society (FRS) in 1968

* Eddington Medal, Royal Astronomical Society (1969)

* Dellinger Gold Medal, International Union of Radio Science (1972)

* Albert A. Michelson Medal, Franklin Institute (1973, jointly with Jocelyn Bell Burnell)

* Fernand Holweck Medal and Prize (1974)

* Nobel Prize for Physics (jointly) (1974)

* Hughes Medal, Royal Society (1976)

* Elected a Fellow of the Institute of Physics (FInstP) in 1998

Personal life

Hewish married Marjorie Elizabeth Catherine Richards in 1950. They had a son, a physicist, and a daughter, a language teacher. Hewish died on 13 September 2021, aged 97.

Religious views

Hewish argued that religion and science are complementary. In the foreword to Questions of Truth, Hewish writes, "The ghostly presence of virtual particles defies rational common sense and is non-intuitive for those unacquainted with physics. Religious belief in God, and Christian belief ... may seem strange to common-sense thinking. But when the most elementary physical things behave in this way, we should be prepared to accept that the deepest aspects of our existence go beyond our common-sense understanding."

It appears to me that if one wants to make progress in mathematics, one should study the masters and not the pupils. - Niels Henrik Abel.

Nothing is better than reading and gaining more and more knowledge - Stephen William Hawking.

Offline

#1778 2025-09-20 18:48:31

- Jai Ganesh

- Administrator

- Registered: 2005-06-28

- Posts: 53,025

Re: crème de la crème

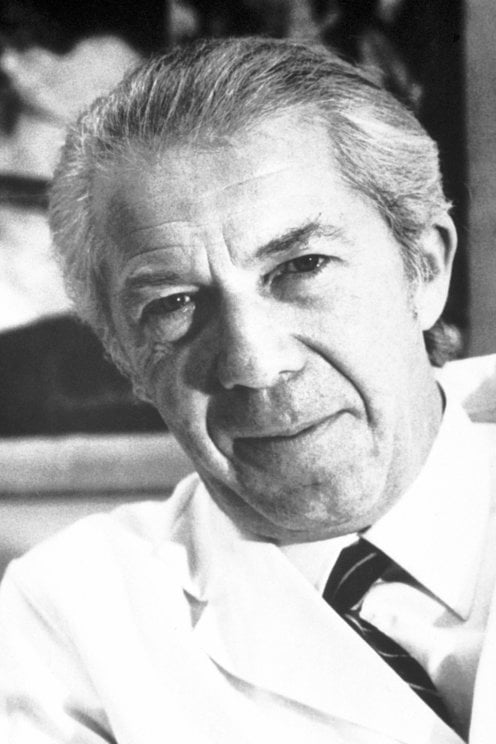

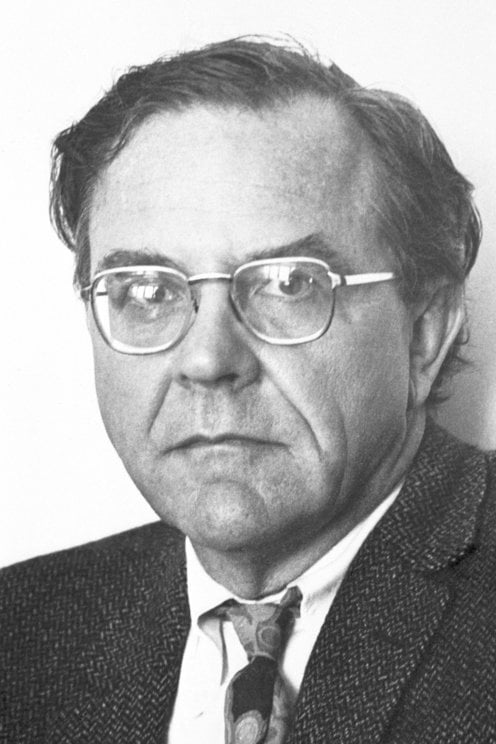

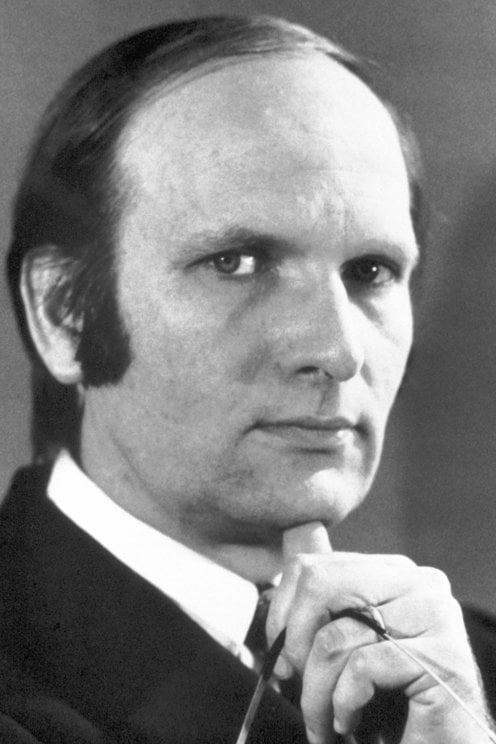

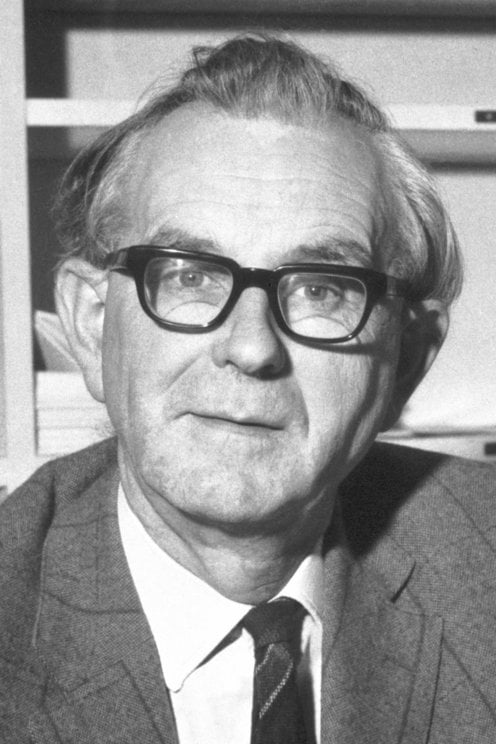

2341) Paul Flory

Gist:

Work

Plastic material is composed of polymers—very large molecules that take the form of long chains of smaller molecules. In the mid-1930s Paul Flory found that a polymer dissolved in a solvent becomes somewhat outstretched because of forces between the polymer’s and the solvent’s parts. When the temperature is lowered, the polymer contracts. Flory established a temperature at which the forces balance one another. The polymer’s length is then similar to its length in an undissolved state. He also defined a constant that summarizes the polymer solution’s properties.

Summary

Paul J. Flory (born June 19, 1910, Sterling, Ill., U.S.—died Sept. 8, 1985, Big Sur, Calif.) was an American polymer chemist who was awarded the 1974 Nobel Prize for Chemistry “for his fundamental achievements, both theoretical and experimental, in the physical chemistry of macromolecules.”

Background and education

Flory was born of Huguenot-German parentage. His father, Ezra Flory, was a Brethren clergyman-educator. His mother, née Martha Brumbaugh, had been a schoolteacher. Flory attended Elgin High School in Elgin, Ill., before enrolling in Manchester College, a Brethren liberal arts college in North Manchester, Ind., in 1927. There, his interest in science was kindled by chemistry professor Carl W. Holl, who encouraged him to apply for graduate school at Ohio State University in Columbus, which had one of the largest chemistry departments in the country. A shy young man, Flory enrolled in 1930 and completed a master’s degree in organic chemistry because he was too insecure about his abilities in mathematics and physics to pursue his main interest, physical chemistry. For his doctorate he did dare to switch to physical chemistry, however, and he defended his thesis, supervised by Herrick L. Johnston, on the photochemistry of nitric oxide in 1934.

Scientific career and achievements

Flory’s professional career included many positions, almost equally divided between industrial and academic institutions. In July 1934, he started to work in the Central Research Department of E.I. du Pont de Nemours and Company under American chemist Wallace Hume Carothers. Carothers had just completed his pathbreaking studies of condensation polymerization, which were widely regarded as definitive proof of the existence of the gigantic long-chain molecules that had been proposed by the German chemist Hermann Staudinger in the 1920s. It was Flory’s task to study the physical chemistry of such macromolecules (or polymers), a subject that would grow into his lifelong occupation. A year after Carothers’ untimely death in 1937, Flory moved to the University of Cincinnati in Ohio. In 1940 he went to work at the laboratories of the Standard Oil Company (New Jersey) in Linden, N.J.; work at the Goodyear Tire & Rubber Company in Akron, Ohio, followed in 1943. In 1948 Flory accepted a lectureship in chemistry at Cornell University in Ithaca, N.Y., a position that turned into a full professorship the same year. After several productive years at Cornell, Flory became executive director of research at the Mellon Institute in Pittsburgh in 1957, a post that he left four years later for Stanford University in California. Flory became emeritus in 1975.

Carothers was the first to show that polymeric substances (such as rubber, cellulose, proteins, plastics, and nylon) could be treated in terms of ordinary chemistry—an approach that inspired Flory. In his first year at DuPont, Flory came up with the “principle of equal reactivity,” which states that chains do not lose their propensity to grow when they get longer, as had been assumed before. On the basis of this principle, Flory calculated a chain length distribution curve, which was experimentally confirmed later. Also during his DuPont years, Flory developed his idea of “chain transfer,” which indicated that a growing addition polymer can transfer its site of growth to a neighbouring molecule by taking over one of its atoms. This insight enabled chemists to control the average chain lengths of polymer products by adding growth-terminating substances—an ability that was exploited during World War II for the U.S. Synthetic Rubber Program, to which Flory contributed at Standard Oil and Goodyear.

Perhaps Flory’s most fundamental contribution was initiated at Standard Oil and elaborated during his Cornell years. Simultaneous with American chemist Maurice Huggins at the Eastman Kodak Company, Flory developed a theory of polymer solutions that accounted for the fact that a polymer chain claims many times the volume of a single chain segment. This phenomenon is expressed in the famous Flory-Huggins, or “volume-fraction,” formula, which gives the entropy of a mixture in a way similar to how the van der Waals equation expresses the behaviour of gases. Another milestone was his analysis of the swelling of a single coil in a good solvent. Flory realized that a chain will avoid intersection with itself and that this avoidance will cause it to swell significantly more than when it could form a random coil. Besides, different sections of the chain attract each other, which leads to a collapse of the coil in poor solvents and at low temperatures. Flory deduced that there would be a “theta state” in which the two effects balanced each other out, so as to make the solution behave ideally. In a polymer melt, he argued with success, all interactions are screened, and ideal random coil behaviour exists as well.

Public and private pursuits

Flory was an active educator of polymer chemistry. His lectures at Cornell laid the basis for Principles of Polymer Chemistry (1953), an introductory textbook that was the standard in the field for several decades. He was an ardent advocate for including the subject in undergraduate curricula, where many polymer chemists felt it continued to be underrepresented in spite of the field’s enormous practical importance. Flory was a consultant to International Business Machines and DuPont for many years and filed 20 patents. His scientific output included more than 300 publications, and he was bestowed with numerous scientific awards.

After receiving the Nobel Prize, he decided to mobilize his public visibility in the battle for the human rights of oppressed scientists, especially in the Soviet Union. Flory was a prime mover in Scientists for Sakharov, Orlov, and Shcharansky (SOS) and the Committee of Concerned Scientists. He often visited dissident scientists and spoke frequently on the Voice of America broadcast to the Soviet Union and Eastern Europe. Much of the background reading and preparation for these activities was done by his wife, née Emily Tabor, whom he had married in 1936. They had three children, all of whom majored in science.

Details

Paul John Flory (June 19, 1910 – September 9, 1985) was an American chemist and Nobel laureate who was known for his work in the field of polymers, or macromolecules. He was a pioneer in understanding the behavior of polymers in solution, and won the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 1974 "for his fundamental achievements, both theoretical and experimental, in the physical chemistry of macromolecules".

Biography:

Personal life

Flory was born in Sterling, Illinois, on June 19, 1910 to Ezra Flory and Martha Brumbaugh. His father worked as a clergyman-educator, and his mother was a school teacher. His ancestors were German Huguenots, who traced their roots back to Alsace. He first gained an interest in science from Carl W Holl, who was a chemistry professor at Manchester College. In 1936, he married Emily Catherine Tabor. They had three children together: Susan Springer, Melinda Groom and Paul John Flory, Jr. His first position was at DuPont with Wallace Carothers. He was posthumously inducted into the Alpha Chi Sigma Hall of Fame in 2002. Flory died on September 9, 1985, following a heart attack. His wife Emily died in 2006 aged 94.

Schooling

After graduating from Elgin High School in 1927, Flory received a bachelor's degree from Manchester College (now Manchester University (Indiana) in 1931 and a Ph.D. from the Ohio State University in 1934. He completed a years of master's study in organic chemistry under the supervision of Prof. Cecil E Boord, before moving into physical chemistry. Flory's doctoral thesis was on the photochemistry of nitric oxide, supervised by Prof. Herrick L. Johnston.

Work

In 1934 Flory joined the Central Department of Dupont and Company working with Wallace H. Carothers. After Carothers' death in 1937, Flory worked for two years at the Basic Research Laboratory located in the University of Cincinnati. During World War II, there was a need for research to develop synthetic rubber, so Flory joined the Esso Laboratories of the Standard Oil Development Company. From 1943 to 1948 Flory worked in the polymer research team of the Goodyear Tire and Rubber Company.

In 1948, Flory gave the George Fisher Baker lectures at Cornell University, and subsequently joined the university as a professor. In 1957, Flory and his family moved to Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, where Flory was executive director of research at the Mellon Institute of Industrial Research. In 1961, he took up a professorship at Stanford University in the department of chemistry. After retirement, Flory remained active in the world of chemistry, running research labs both in Stanford, and IBM.

Research:

Career and polymer science

Flory's earliest work in polymer science was in the area of polymerization kinetics at the DuPont Experimental Station. In condensation polymerization, he challenged the assumption that the reactivity of the end group decreased as the macromolecule grew, and by arguing that the reactivity was independent of the size, he was able to derive the result that the number of chains present decreased with size exponentially. In addition polymerization, he introduced the important concept of chain transfer to improve the kinetic equations and remove difficulties in understanding the polymer size distribution.

In 1938, after Carothers' death, Flory moved to the Basic Science Research Laboratory at the University of Cincinnati. There he developed a mathematical theory for the polymerization of compounds with more than two functional groups and the theory of polymer networks or gels. This led to the Flory-Stockmayer theory of gelation, which was equivalent to percolation on the Bethe lattice and represents the first paper in the percolation field.

In 1940 he joined the Linden, NJ laboratory of the Standard Oil Development Company where he developed a statistical mechanical theory for polymer mixtures. In 1943 he left to join the research laboratories of Goodyear as head of a group on polymer fundamentals. In the Spring of 1948 Peter Debye, then chairman of the chemistry department at Cornell University, invited Flory to give the annual Baker Lectures. He then was offered a position with the faculty in the Fall of the same year. He was initiated into the Tau chapter of Alpha Chi Sigma at Cornell in 1949. At Cornell he elaborated and refined his Baker Lectures into his magnum opus, Principles of Polymer Chemistry which was published in 1953 by Cornell University Press. This quickly became a standard text for all workers in the field of polymers, and is still widely used to this day.

Flory introduced the concept of excluded volume, coined by Werner Kuhn in 1934, to polymers. Excluded volume refers to the idea that one part of a long chain molecule can not occupy space that is already occupied by another part of the same molecule. Excluded volume causes the ends of a polymer chain in a solution to be further apart (on average) than they would be were there no excluded volume. The recognition that excluded volume was an important factor in analyzing long-chain molecules in solutions provided an important conceptual breakthrough, and led to the explanation of several puzzling experimental results of the day. It also led to the concept of the theta point, the set of conditions at which an experiment can be conducted that causes the excluded volume effect to be neutralized. At the theta point, the chain reverts to ideal chain characteristics – the long-range interactions arising from excluded volume are eliminated, allowing the experimenter to more easily measure short-range features such as structural geometry, bond rotation potentials, and steric interactions between near-neighboring groups. Flory correctly identified that the chain dimension in polymer melts would have the size computed for a chain in ideal solution if excluded volume interactions were neutralized by experimenting at the theta point.

Among his accomplishments are an original method for computing the probable size of a polymer in good solution, the Flory-Huggins Solution Theory, the extension of polymer physics concepts to the field of liquid crystals, and the derivation of the Flory exponent, which helps characterize the movement of polymers in solution.

The Flory convention

In modeling the position vectors of atoms in macromolecules it is often necessary to convert from Cartesian coordinates (x,y,z) to generalized coordinates. The Flory convention for defining the variables involved is usually employed. For an example, a peptide bond can be described by the x,y,z positions of every atom in this bond or the Flory convention can be used. [b

Awards and honors

Flory was elected to the United States National Academy of Sciences in 1953 and the American Academy of Arts and Sciences in 1957. In 1968, he received the Charles Goodyear Medal. He also received the Priestley Medal and the Golden Plate Award of the American Academy of Achievement in 1974. He received the Carl-Dietrich-Harries-Medal for commendable scientific achievements in 1977. Flory received the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 1974 "for his fundamental achievements both theoretical and experimental, in the physical chemistry of the macromolecules." Additionally in 1974 Flory was awarded the National Medal of Science in Physical Sciences. The medal was presented to him by President Gerald Ford. This award was given to him because of his research on the "formation and structure of polymeric substances".

It appears to me that if one wants to make progress in mathematics, one should study the masters and not the pupils. - Niels Henrik Abel.

Nothing is better than reading and gaining more and more knowledge - Stephen William Hawking.

Offline

#1779 2025-09-21 20:07:12

- Jai Ganesh

- Administrator

- Registered: 2005-06-28

- Posts: 53,025

Re: crème de la crème

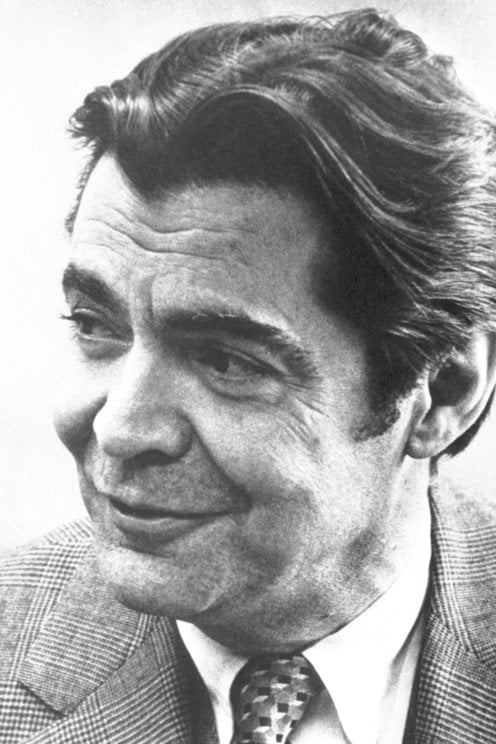

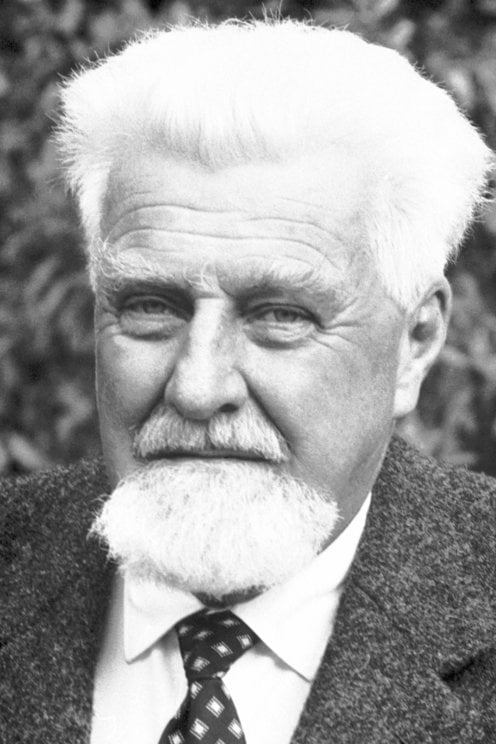

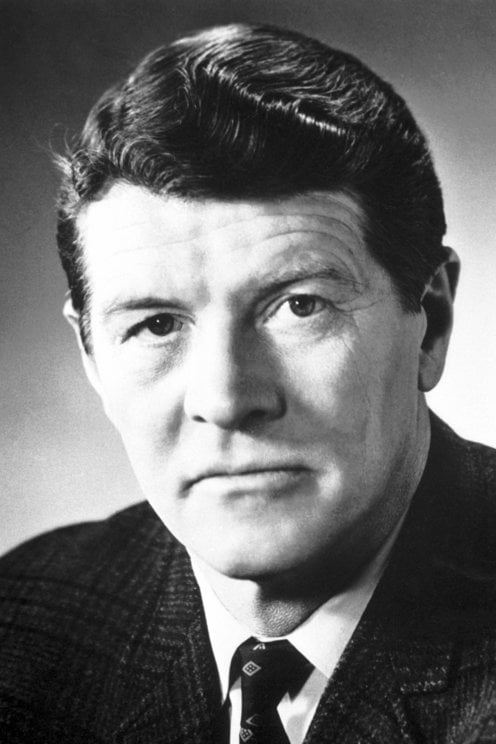

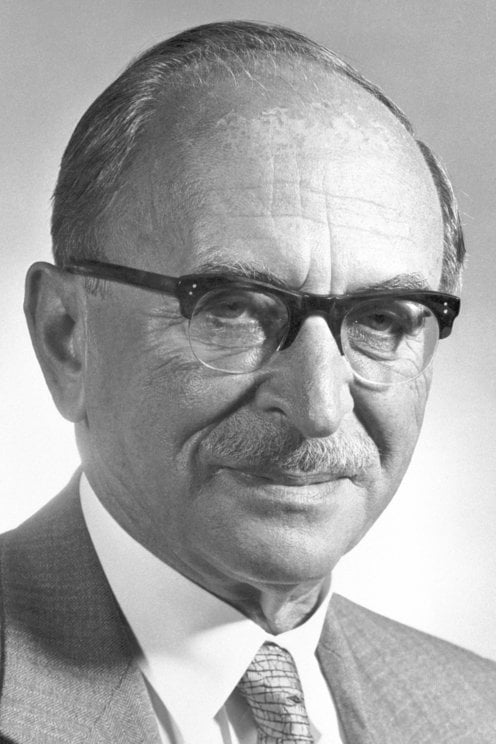

2342) Albert Claude

Gist:

Work

Our bodies are made up of cells that contain organelles, components with various functions. Around 1945 Albert Claude conducted a number of trailblazing studies of cellular components. He made use of the newly developed electron microscope, which enabled him to capture images with a level of detail not previously available. Claude also developed methods for separating the various parts of pulverized cells with a centrifuge so they could be better studied. This also became a breakthrough for cell biology.

Summary

Albert Claude (born August 24, 1898, Longlier, Belgium—died May 22, 1983, Brussels) was a Belgian-American cytologist who developed the principal methods of separating and analyzing components of the living cell. For this work, on which modern cell biology is partly based, Claude, his student George Palade, and Christian de Duve shared the Nobel Prize for Physiology or Medicine in 1974.

Upon obtaining his M.D. at Liège University, Belgium, in 1928, Claude began research at the Rockefeller Institute for Medical Research (now Rockefeller University) in New York City. In attempting to isolate the Rous sarcoma virus from chicken tumours, he spun cell extracts containing the virus in centrifuges that concentrated heavier particles in the bottom of the test tube; lighter particles settled in layers above. For comparison, he began centrifuging normal cells. This centrifugal separation of the cell components made possible a biochemical analysis of them that confirmed that the separated particles consisted of distinct organelles. Such analysis enabled Claude to discover the endoplasmic reticulum (a membranous network within cells) and to clarify the function of the mitochondria (see Figure) as the centres of respiratory activity.

Claude turned in 1942 to the electron microscope—an instrument that had not been used in biological research—looking first at separated components, then at whole cells. His demonstration of the instrument’s usefulness in this regard eventually helped scientists to correlate the biological activity of each cellular component with its structure and its place in the cell.

Claude, who became a citizen of the United States in 1941, returned in 1949 to Belgium; through a legal process, he held dual citizenship in the two countries from 1949. While holding professorships at Rockefeller University (to 1972) and the Université Libre in Brussels (to 1969), he served as director (1948–71) of the Jules Bordet Institute.

Details

Albert Claude (24 August 1899 – 22 May 1983) was a Belgian-American cell biologist and medical doctor who shared the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1974 with Christian de Duve and George Emil Palade. His elementary education started in a comprehensive primary school at Longlier, his birthplace. He served in the British Intelligence Service during the First World War, and got imprisoned in concentration camps twice. In recognition of his service, he was granted enrolment at the University of Liège in Belgium to study medicine without any formal education required for the course. He earned his Doctor of Medicine degree in 1928. Devoted to medical research, he initially joined German institutes in Berlin. In 1929 he found an opportunity to join the Rockefeller Institute in New York. At Rockefeller University he made his most groundbreaking achievements in cell biology. In 1930 he developed the technique of cell fractionation, by which he discovered the agent of the Rous sarcoma, as well as components of cell organelles such as the mitochondrion, chloroplast, endoplasmic reticulum, Golgi apparatus, ribosome, and lysosome. He was the first to employ the electron microscope in the field of biology. In 1945 he published the first detailed structure of cell. His collective works established the complex functional and structural properties of cells.

Claude served as director at Jules Bordet Institute for Cancer Research and Treatment and Laboratoire de Biologie Cellulaire et Cancérologie in Louvain-la-Neuve ; Professor at the Free University of Brussels, the University of Louvain, and Rockefeller University. For his pioneering works he received the Louisa Gross Horwitz Prize in 1970, together with his student George Palade and Keith Porter, the Paul Ehrlich and Ludwig Darmstaedter Prize in 1971, and the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1974 with Palade and his friend Christian de Duve.

Early life and education

Albert Claude was born in 1899 (but according to civil register 1898) in Longlier, a hamlet in Neufchâteau, Belgium, to Florentin Joseph Claude and Marie-Glaudice Watriquant Claude. He was the youngest among three brothers and one sister. His father was a Paris-trained baker and ran a bakery-cum-general store at Longlier valley near railroad station. His mother, who developed breast cancer in 1902, died when he was seven years old. He spent his pre-school life with his ailing mother. He started education in Longlier Primary School, a pluralistic school of single room, mixed grades, and all under one teacher. In spite of the inconveniences, he remarked the education system as "excellent." He served as a bell boy, ringing the church bell every morning at 6. Due to economic depression the family moved to Athus, a prosperous region with steel mills, in 1907. He entered German-speaking school. After two years he was asked to look after his uncle who was disabled with cerebral haemorrhage in Longlier. He dropped out of school and practically nursed his uncle for several years. At the outbreak of the First World War he was apprenticed to steel mills and worked as an industrial designer. Inspired by Winston Churchill, then British Minister of War, he joined the resistance and volunteered in British Intelligence Service in which he served during the whole war. At the end of the war he was decorated with the Interallied Medal along with veteran status. He then wanted to continue education. Since he had no formal secondary education, particularly required for medicine course, such as in Greek and Latin, he tried to join School of Mining in Liège. By that time Marcel Florkin became head of the Direction of Higher Education in Belgium's Ministry of Public Instruction, and under his administration passed the law that enabled war veterans to pursue higher education without diploma or other examinations. As an honour to his war service, he was given admission to the University of Liège in 1922 to study medicine. He obtained his degree of Doctor of Medicine in 1928.

Career

Claude received travel grants from Belgian government for his doctoral thesis on the transplantation of mouse cancers into rats. With this he worked his postdoctoral research in Berlin during the winter of 1928–1929, first at the Institut für Krebsforschung, and then at the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute for Biology, Dahlem, in the laboratory of tissues culture of Prof. Albert Fischer. Back in Belgium he received fellowship in 1929 from the Belgian American Educational Foundation (Commission for Relief in Belgium, CRB) for research in the United States. He applied for the Rockefeller Institute (now the Rockefeller University) in New York, USA. Simon Flexner, then Director, accepted his proposal to work on the isolation and identification of the Rous sarcoma virus. In September 1929 he joined the Rockefeller Institute. In 1930, he discovered the process of cell fractionation, which was groundbreaking in his time. The process consists of grinding up cells to break the membrane and release the cell's contents. He then filtered out the cell membranes and placed the remaining cell contents in a centrifuge to separate them according to mass. He divided the centrifuged contents into fractions, each of a specific mass, and discovered that particular fractions were responsible for particular cell functions. In 1938 he identified and purified for the first time component of Rous sarcoma virus, the causal agent of carcinoma, as "ribose nucleoprotein" (eventually named RNA). He was the first to use electron microscope to study biological cells. Earlier electron microscopes were used only in physical researches. His first electron microscopic study was on the structure of mitochondria in 1945. He was given American citizenship in 1941. He discovered that mitochondria are the "power houses" of all cells. He also discovered cytoplasmic granules full of RNA and named them "microsomes", which were later renamed ribosomes, the protein synthesizing machineries of cell. With his associate, Keith Porter, he found a "lace-work" structure that was eventually proven to be the major structural feature of the interior of all eukaryotic cells. This was the discovery of endoplasmic reticulum (a Latin for "fishnet").

In 1949, he became Director of the Jules Bordet Institute for Cancer Research and Treatment (Institut Jules Bordet) and Professor at the Faculty of Medicine of the Free University of Brussels, where he was Emeritus in 1971.

In the mid sixties during an Electron Microscopy symposium in (Bratislava)-(Czechoslovakia) organized by the (UNESCO) at the Czechoslovak Academy of Sciences, he meets young scientist Dr. Emil Mrena who was at that time head of the Electron Microscopy department. He invited him to come and work with him in Brussels, making it possible for Dr. Mrena's family to escape the communist regime. Their close collaboration gave fruition to 5 publications from 1969 to 1974. With the support of his colleague and friend Christian de Duve, he became in 1972 Professor at the University of Louvain (Université catholique de Louvain) and Director of the "Laboratoire de Biologie Cellulaire et Cancérologie" in Louvain-la-Neuve where he moved with Dr. Emil Mrena as sole collaborator. At the same time, he was appointed Professor at the Rockefeller University, an institution with which he had remained connected, in different degrees, since 1929.

Personal life

He married Julia Gilder in 1935, with whom he had a daughter, Philippa. They were divorced while he was at Rockefeller. Philippa became a neuroscientist and married Antony Stretton.

Claude was known to be a bit of an eccentric and had close friendship with painters, including Diego Rivera and Paul Delvaux, and musicians such as Edgard Varèse.

After his retirement in 1971 from the Université libre de Bruxelles and from the directorship of the Institut Jules Bordet, he continued his research at the University of Louvain with his collaborator Dr. Emil Mrena, who ended up resigning in 1977 due to decreasing activity of the Laboratory, moving to other research works. It is said that he continued his research in seclusion until he died of natural causes, at his home in Brussels, on Sunday night on 22 May 1983, but he had stopped visiting his own laboratory in Louvain already in 1976 due to his weak health.

It appears to me that if one wants to make progress in mathematics, one should study the masters and not the pupils. - Niels Henrik Abel.

Nothing is better than reading and gaining more and more knowledge - Stephen William Hawking.

Offline

#1780 2025-09-22 20:26:32

- Jai Ganesh

- Administrator

- Registered: 2005-06-28

- Posts: 53,025

Re: crème de la crème

2343) Christian de Duve

Gist:

Work

Our bodies are made up of cells that contain organelles, components with various functions. Albert Claude’s research with the newly developed electron microscope and his methods for separating the various parts of pulverized cells using a centrifuge opened up new opportunities for studying cells in detail. In 1955 Christian de Duve discovered previously unknown organelles in the cell, lysosomes. These have important functions in decomposing different types of materials, such as bacteria and parts of cells that have worn out.

Summary

Christian René de Duve (born October 2, 1917, Thames Ditton, Surrey, England—died May 4, 2013, Nethen, Belgium) was a Belgian cytologist and biochemist who discovered lysosomes (the digestive organelles of the cell) and peroxisomes (organelles that are the site of metabolic processes involving hydrogen peroxide). For this work he shared the Nobel Prize for Physiology or Medicine in 1974 with Albert Claude and George Palade.

De Duve’s discovery of lysosomes arose out of his research on the enzymes involved in the metabolism of carbohydrates by the liver. While using Claude’s technique of separating the components of cells by spinning them in a centrifuge, he noticed that the cells’ release of an enzyme called acid phosphatase increased in proportion to the amount of damage done to the cells during centrifugation. De Duve reasoned that the acid phosphatase was enclosed within the cell in some kind of membranous envelope that formed a self-contained organelle. He calculated the probable size of this organelle, christened it the lysosome, and later identified it in electron microscope pictures. De Duve’s discovery of lysosomes answered the question of how the powerful enzymes used by cells to digest nutrients are kept separate from other cell components.

In 1947 de Duve joined the faculty of the Catholic University of Leuven (Louvain) in Belgium, where he had received an M.D. in 1941 and a master’s degree in chemistry in 1946. From 1962 he simultaneously headed research laboratories at Leuven, where he became emeritus professor in 1985, and at Rockefeller University, New York City, where he was named emeritus professor in 1988. De Duve also founded the International Institute of Cellular and Molecular Pathology (ICP) in 1974, which was renamed the Christian de Duve Institute of Cellular Pathology in 1997.

Details

Christian René Marie Joseph, Viscount de Duve (2 October 1917 – 4 May 2013) was a Nobel Prize-winning Belgian cytologist and biochemist. He made serendipitous discoveries of two cell organelles, peroxisomes and lysosomes, for which he shared the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1974 with Albert Claude and George E. Palade ("for their discoveries concerning the structural and functional organization of the cell"). In addition to peroxisome and lysosome, he invented scientific names such as autophagy, endocytosis, and exocytosis on a single occasion.

The son of Belgian refugees during the First World War, de Duve was born in Thames Ditton, Surrey, England. His family returned to Belgium in 1920. He was educated by the Jesuits at Our Lady College, Antwerp, and studied medicine at the Catholic University of Louvain. Upon earning his MD in 1941, he joined research in chemistry, working on insulin and its role in diabetes mellitus. His thesis earned him the highest university degree agrégation de l'enseignement supérieur (equivalent to PhD) in 1945.

With his work on the purification of penicillin, he obtained an MSc degree in 1946. He went for further training under later Nobel Prize winners Hugo Theorell at the Karolinska Institutet in Stockholm, and Carl and Gerti Cori at the Washington University in St. Louis. He joined the faculty of medicine at Leuven in 1947. In 1960 he was invited to the Rockfeller Institute (now Rockefeller University). With mutual arrangement with Leuven, he became professor in both universities from 1962, dividing his time between Leuven and New York. In 1974, the same year he received his Nobel Prize, he founded the ICP, which would later be renamed the de Duve Institute. He became emeritus professor of the University of Louvain in 1985, and of Rockefeller in 1988.

De Duve was granted the rank of Viscount in 1989 by King Baudouin of Belgium. He was also a recipient of Francqui Prize, Gairdner Foundation International Award, Heineken Prize, and E.B. Wilson Medal. In 1974, he founded the International Institute of Cellular and Molecular Pathology in Brussels, eventually renamed the de Duve Institute in 2005. He was the founding President of the L'Oréal-UNESCO For Women in Science Awards. He died by legal euthanasia after long suffering from cancer and atrial fibrillation.

Early life and education

De Duve was born of an estate agent Alphonse de Duve and wife Madeleine Pungs in the village of Thames Ditton, near London. His parents fled Belgium at the outbreak of the First World War. After the war in 1920, at age three, he and his family returned to Belgium. He was a precocious boy, always the best student (primus perpetuus as he recalled) in school, except for one year when he was pronounced "out of competition" to give chance to other students.

He was educated by the Jesuits at Onze-Lieve-Vrouwinstituut in Antwerp, before studying at the Catholic University of Louvain in 1934. He wanted to specialize in endocrinology and joined the laboratory of the Belgian physiologist Joseph P. Bouckaert, whose primary interest was one insulin. During his last year at medical school in 1940, the Germans invaded Belgium. He was drafted to the Belgian army, and posted in southern France as medical officer. There, he was almost immediately taken as prisoner of war by Germans. His ability to speak fluent German and Flemish helped him outwit his captors. He escaped back to Belgium in an adventure he later described as "more comical than heroic".

He immediately continued his medical course, and obtained his MD in 1941 from Leuven. After graduation, de Duve continued his primary research on insulin and its role in glucose metabolism. He (with Earl Sutherland) made an initial discovery that a commercial preparation of insulin was contaminated with another pancreatic hormone, the insulin antagonist glucagon. However, laboratory supplies at Leuven were in shortage, therefore he enrolled in a programme to earn a degree in chemistry at the Cancer Institute. His research on insulin was summed up in a 400-page book titled Glucose, Insuline et Diabète (Glucose, Insulin and Diabetes) published in 1945, simultaneously in Brussels and Paris. The book was condensed into a technical dissertation which earned him the most advanced degree at the university level agrégation de l'enseignement supérieur (an equivalent of a doctorate – he called it "a sort of glorified PhD") in 1945. His thesis was followed by a number of scientific publications. He subsequently obtained a MSc in chemistry in 1946, for which he worked on the purification of penicillin.

To enhance his skill in biochemistry, he trained in the laboratory of Hugo Theorell (who later won The Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1955) at the Nobel Medical Institute in Stockholm for 18 months during 1946–47. In 1947, he received a financial assistance as Rockefeller Foundation fellow and worked for six months with Carl and Gerti Cori at Washington University in St. Louis (the husband and wife were joint winners of The Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1947).

Career and research

In March 1947 de Duve joined the faculty of the medical school of the Catholic University of Leuven teaching physiological chemistry. In 1951 he became full professor. In 1960, Detlev Bronk, the then president of the Rockfeller Institute (what is now Rockefeller University) of New York City, met him at Brussels and offered him professorship and a laboratory. The rector of Leuven, afraid of entirely losing de Duve, made a compromise over dinner that de Duve would still be under part-time appointment with a relief from teaching and conducting examinations. The rector and Bronk made an agreement which would initially last for five years. The official implementation was in 1962, and de Duve simultaneously headed the research laboratories at Leuven and at Rockefeller University, dividing his time between New York and Leuven.

In 1969, the Catholic University of Leuven was contentiously split into two separate universities along linguistic lines. De Duve chose to join the French-speaking side, Université catholique de Louvain. He took emeritus status at the University of Louvain in 1985 and at Rockefeller in 1988, though he continued to conduct research. Among other subjects, he studied the distribution of enzymes in rat liver cells using rate-zonal centrifugation. His work on cell fractionation provided an insight into the function of cell structures. He specialized in subcellular biochemistry and cell biology and discovered new cell organelles.

Rediscovery of glucagon

The hormone glucagon was discovered by C.P. Kimball and John R. Murlin in 1923 as a hyperglycaemic (blood-sugar elevating) substance among the pancreatic extracts. The biological importance of glucagon was not known and the name itself was essentially forgotten. It was a still a mystery at the time de Duve joined Bouckaert at Leuven University to work on insulin. Since 1921, insulin was the first commercial hormonal drug originally produced by the Eli Lilly and Company, but their extraction methods introduced an impurity that caused mild hyperglycaemia, the very opposite of what was expected or desired. In May 1944 de Duve realised that crystallisation could remove the impurity. He demonstrated that Lilly's insulin process was contaminated, showing that, when injected into rats, the Lilly insulin caused initial hyperglycaemia and the Danish Novo insulin did not. Following his research published in 1947, Lilly upgraded its methods to eliminate the impurity. By then de Duve had joined Carl Cori and Gerty Cori at Washington University in St. Louis, where he worked with a fellow researcher Earl Wilbur Sutherland, Jr., who later won the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1971.

Sutherland had been working on the puzzle of the insulin-impurity substance, which he had named hyperglycemic-glycogenolytic (HG) factor. He and de Duve soon discovered that the HG factor was synthesised not only by the pancreas but also by the gastric mucosa and certain other parts of the digestive tract. Further, they found that the hormone was produced from pancreatic islets by cells differing from the insulin-producing beta cells; presumably these were alpha cells. It was de Duve who realised that Sutherland's HG factor was in fact the same as glucagon; this rediscovery led to its permanent name, which de Duve reintroduced it in 1951. The pair's work showed that glucagon was the major hormone influencing the breakdown of glycogen in the liver—the process known as glycogenolysis—by which more sugars are produced and released into the blood.

De Duve's original hypothesis that glucagon was produced by pancreatic alpha cells was proven correct when he demonstrated that selectively cobalt-damaged alpha cells stopped producing glucagon in guinea pigs; he finally isolated the purified hormone in 1953, including those from birds.

De Duve was first to hypothesise that the production of insulin (which decreased blood sugar levels), stimulated the uptake of glucose in the liver; he also proposed that a mechanism was in-place to balance the productions of insulin and glucagon in order to maintain normal blood sugar level, (see homeostasis). This idea was much disputed at the time, but his rediscovery of glucagon confirmed his theses. In 1953 he experimentally demonstrated that glucagon did influence the production (and thus the uptake) of glucose.

Discovery of lysosome

Christian de Duve and his team continued studying the insulin mechanism-of-action in liver cells, focusing on the enzyme glucose 6-phosphatase, the key enzyme in sugar metabolism (glycolysis) and the target of insulin. They found that G6P was the principal enzyme in regulating blood sugar levels, but, they could not, even after repeated experiments, purify and isolate the enzyme from the cellular extracts. So they tried the more laborious procedure of cell fractionation to detect the enzyme activity.

This was the moment of serendipitous discovery. To estimate the exact enzyme activity, the team adopted a procedure using a standardised enzyme acid phosphatase; but they were finding the activity was unexpectedly low—quite low, i.e., some 10% of the expected value. Then one day they measured the enzyme activity of some purified cell fractions that had been stored for five days. To their surprise the enzyme activity was increased back to that of the fresh sample; and similar results were replicated every time the procedure was repeated. This led to the hypothesis that some sort of barrier restricted rapid access of the enzyme to its substrate, so that the enzymes were able to diffuse only after a period of time. They described the barrier as membrane-like—a "saclike structure surrounded by a membrane and containing acid phosphatase."

An unrelated enzyme (of the cell fractionation procedure) had come from membranous fractions that were known to be cell organelles. In 1955, de Duve named them "lysosomes" to reflect their digestive properties. That same year, Alex B. Novikoff from the University of Vermont visited de Duve's laboratory, and, using electron microscopy, successfully produced the first visual evidence of the lysosome organelle. Using a staining method for acid phosphatase, de Duve and Novikoff further confirmed the location of the hydrolytic enzymes (acid hydrolases) of lysosomes.

Discovery of peroxisome

Serendipity followed de Duve for another major discovery. After the confirmation of lysosome, de Duve's team was troubled by the presence (in the rat liver cell fraction) of the enzyme urate oxidase. De Duve thought it was not a lysosome because it is not an acid hydrolase, typical of lysosomal enzymes; still, it had similar distribution as the enzyme acid phosphatase. Further, in 1960 he found other enzymes (such as catalase and D-amino acid oxidase), that were similarly distributed in the cell fraction—and it was then thought that these were mitochondrial enzymes. (W. Bernhard and C. Rouillier had described such extra-mitochondrial organelles as microbodies, and believed that they were precursors to mitochondria.) de Duve noted the three enzymes exhibited similar chemical properties and were similar to those of other peroxide-producing oxidases.

De Duve was skeptical of referring to the new-found enzymes as microbodies because, as he noted, "too little is known of their enzyme complement and of their role in the physiology of the liver cells to substantiate a proposal at the present time". He suggested that these enzymes belonged to the same cell organelle, but one different from previously known organelles. But, as strong evidences were still lacking, he did not publish his hypothesis. In 1955 his team demonstrated similar cell fractions with same biochemical properties from the ciliated protozoan Tetrahymena pyriformis; thus, it was indicated that the particles were undescribed cell organelles unrelated to mitochondria. He presented his discovery at a meeting of the American Society for Cell Biology in 1955, and formally published in 1966, creating the name peroxisomes for the organelles as they are involved in peroxidase reactions. In 1968 he achieved the first large-scale preparation of peroxisomes, confirming that l-α hydroxyacid oxidase, d-amino acid oxidase, and catalase were all the unique enzymes of peroxisomes.

De Duve and his team went on to show that peroxisomes play important metabolic roles, including the β-oxidation of very long-chain fatty acids by a pathway different from that in mitochondria; and that they are members of a large family of evolutionarily related organelles present in diverse cells including plants and protozoa, where they carry out distinct functions. (And have been given specific names, such as glyoxysomes and glycosomes.)

Origin of cells

De Duve's work has contributed to the emerging consensus towards accepting the endosymbiotic theory; which idea proposes that organelles in eukaryotic cells originated as certain prokaryotic cells that came to live inside eukaryotic cells as endosymbionts. According to de Duve's version, eukaryotic cells with their structures and properties, including their ability to capture food by endocytosis and digest it intracellularly, developed first. Later, prokaryotic cells were incorporated to form more organelles.

De Duve proposed that peroxisomes, which allowed cells to withstand the growing amounts of free molecular oxygen in the early-Earth atmosphere, may have been the first endosymbionts. Because peroxisomes have no DNA of their own, this proposal has much less evidence than similar claims for mitochondria and chloroplasts. His later years were mostly devoted to origin of life studies, which he admitted was still a speculative field.

It appears to me that if one wants to make progress in mathematics, one should study the masters and not the pupils. - Niels Henrik Abel.

Nothing is better than reading and gaining more and more knowledge - Stephen William Hawking.

Offline

#1781 2025-09-23 19:09:46

- Jai Ganesh

- Administrator

- Registered: 2005-06-28

- Posts: 53,025

Re: crème de la crème

2344) George Emil Palade

Gist:

Work

Our bodies are made up of cells that contain organelles, components with various functions. Albert Claude’s research with the newly developed electron microscope and his methods for separating the various parts of pulverized cells using a centrifuge opened up new opportunities for studying cells in detail. In 1955 George Palade discovered previously unknown organelles in the cell, ribosomes, where the cell’s formation of proteins takes place. He also identified the paths proteins take through the cell.

Summary

George E. Palade (born Nov. 19, 1912, Iaşi, Rom.—died Oct. 7, 2008, Del Mar, Calif., U.S.) was a Romanian-born American cell biologist who developed tissue-preparation methods, advanced centrifuging techniques, and conducted electron microscopy studies that resulted in the discovery of several cellular structures. With Albert Claude and Christian de Duve he was awarded the Nobel Prize for Physiology or Medicine in 1974.

Palade received a degree in medicine from the University of Bucharest in 1940 and remained there as a professor until after World War II. He immigrated to the United States in 1946 and began work at the Rockefeller Institute in New York. Palade performed many studies on the internal organization of such cell structures as mitochondria, chloroplasts, the Golgi apparatus, and others. His most important discovery was that microsomes, bodies formerly thought to be fragments of mitochondria, are actually parts of the endoplasmic reticulum (internal cellular transport system) and have a high ribonucleic acid (RNA) content. They were subsequently named ribosomes.

Palade became a naturalized citizen of the United States in 1952 and in 1958 a professor of cytology at Rockefeller Institute, which he left in 1972 to direct studies in cell biology at Yale University Medical School. In 1990 Palade moved to the University of California, San Diego (UCSD) School of Medicine, where he acted as dean for scientific affairs, served as professor of medicine, and established an exceptional cell biology program. Palade retired in 2001, becoming professor emeritus of medicine at UCSD. In addition to the Nobel Prize, Palade received the Albert Lasker Award for Basic Medical Research (1966) and the National Medal of Science (1986).

Details

George Emil Palade (November 19, 1912 – October 7, 2008) was a Romanian-American cell biologist. In 1974 he was awarded the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine along with Albert Claude and Christian de Duve. The prize was granted for his innovations in electron microscopy and cell fractionation which together laid the foundations of modern molecular cell biology, the most notable discovery being the ribosomes of the endoplasmic reticulum – which he first described in 1955.

Palade also received the U.S. National Medal of Science in Biological Sciences for "pioneering discoveries of a host of fundamental, highly organized structures in living cells" in 1986, and was previously elected a Member of the U.S. National Academy of Sciences in 1961. In 1968 he was elected as an Honorary Fellow of the Royal Microscopical Society (HonFRMS) and in 1984 he became a Foreign Member of the Royal Society (ForMemRS).

Education and early life

George Emil Palade was born on November 19, 1912, in Iași, Romania. Palade's father was a professor of philosophy at the University of Iași and his mother was a high school teacher. Palade received his M.D. in 1940 from the Carol Davila School of Medicine in Bucharest.

Career and research

Palade was a member of the faculty at University of Bucharest until 1946, when he went to the United States to do postdoctoral research. While assisting Robert Chambers in the Biology Laboratory of New York University, he met Professor Albert Claude. He later joined Claude at the Rockefeller Institute for Medical Research.

In 1952, Palade became a naturalized citizen of the United States. He worked at the Rockefeller Institute (1958–1973), and was a professor at Yale University Medical School (1973–1990), and University of California, San Diego (1990–2008). At UCSD, Palade was Professor of Medicine in Residence (Emeritus) in the Department of Cellular & Molecular Medicine, as well as a Dean for Scientific Affairs (Emeritus), in the School of Medicine at La Jolla, California.

In 1970, he was awarded the Louisa Gross Horwitz Prize from Columbia University, together with Renato Dulbecco (winner of the 1975 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine) "for discoveries concerning the functional organization of the cell that were seminal events in the development of modern cell biology", related to his previous research carried out at the Rockefeller Institute for Medical Research. His Nobel lecture, delivered on December 12, 1974, was entitled: "Intracellular Aspects of the Process of Protein Secretion", published in 1992 by the Nobel Prize Foundation, He was elected an Honorary member of the Romanian Academy in 1975. He received the Golden Plate Award of the American Academy of Achievement in 1975. In 1981, Palade became a founding member of the World Cultural Council. In 1985, he became the founding editor of the Annual Review of Cell and Developmental Biology. In 1988 he was also elected an Honorary Member of the American-Romanian Academy of Arts and Sciences (ARA).

Palade was the first Chairman of the Department of Cell Biology at Yale University. Presently, the Chair of Cell Biology at Yale is named the "George Palade Professorship".

At the Rockefeller Institute for Medical Research, Palade used electron microscopy to study the internal organization of such cell structures as ribosomes, mitochondria, chloroplasts, the Golgi apparatus, and others. His most important discovery was made while using an experimental strategy known as a pulse-chase analysis. In the experiment Palade and his colleagues were able to confirm an existing hypothesis that a secretory pathway exists and that the Rough ER and the Golgi apparatus function together.

He focused on Weibel-Palade bodies (a storage organelle unique to the endothelium, containing von Willebrand factor and various proteins) which he described together with the Swiss anatomist Ewald R. Weibel.

He was a member of the American Association for Anatomy.

Palade's coworkers and approach in the 1960s

The following is a concise excerpt from Palade's Autobiography appearing in the Nobel Award documents

In the 1960s, I continued the work on the secretory process using in parallel or in succession two different approaches. The first relied exclusively on cell fractionation, and was developed in collaboration with Philip Siekevitz, Lewis Joel Greene, Colvin Redman, David Sabatini, and Yutaka Tashiro; it led to the characterization of the zymogen granules and to the discovery of the segregation of secretory products in the cisternal space of the endoplasmic reticulum. The second approach relied primarily on radioautography, and involved experiments on intact animals or pancreatic slices which were carried out in collaboration with Lucien Caro and especially James Jamieson. This series of investigations produced a good part of our current ideas on the synthesis and intracellular processing of proteins for export. A critical review of this line of research is presented in the Nobel Lecture.

One notes also that the Nobel Prize in Chemistry was awarded in 2009 to Venkatraman Ramakrishnan, Thomas A. Steitz, and Ada E. Yonath "for studies of the structure and function of the ribosome", discovered by George Emil Palade.

Personal life

He married Irina Malaxa (born in 1919, the daughter of industrialist Nicolae Malaxa) on June 12, 1941. The couple had two children: Georgia (born in 1943) and Theodore (born in 1949). After his wife died in 1969, Palade married Marilyn Farquhar, a cell biologist at the University of California, San Diego.

It appears to me that if one wants to make progress in mathematics, one should study the masters and not the pupils. - Niels Henrik Abel.

Nothing is better than reading and gaining more and more knowledge - Stephen William Hawking.

Offline

#1782 2025-09-24 20:42:00

- Jai Ganesh

- Administrator

- Registered: 2005-06-28

- Posts: 53,025

Re: crème de la crème

2345) Leo Esaki

Gist:

Work

In quantum physics matter is described as both waves and particles. One result of this is the tunneling phenomenon, which means that particles can pass through barriers that they should not be able to squeeze through according to classic physics. Through a seemingly simple experiment in 1958, Leo Esaki demonstrated a previously unknown type of tunneling in semiconductor material, material that is a cross between electrical conductors and insulators. The discovery is utilized in semiconductors known as tunnel diodes. It also led to further research on semiconductors.

Summary

Leo Esaki (born March 12, 1925, Ōsaka, Japan) is a Japanese solid-state physicist and researcher in superconductivity who shared the Nobel Prize for Physics in 1973 with Ivar Giaever and Brian Josephson.

Esaki was a 1947 graduate in physics from Tokyo University and immediately joined the Kobe Kogyo company. In 1956 he became chief physicist of the Sony Corporation, where he conducted the experimentation that led to the Nobel Prize. In 1959 he received a Ph.D. from Tokyo University.

Esaki’s work at Sony was in the field of quantum mechanics and concentrated on the phenomenon of tunneling, in which the wavelike character of matter enables electrons to pass through barriers that the laws of classical mechanics say are impenetrable. He devised ways to modify the behaviour of solid-state semiconductors by adding impurities, or “doping” them. This work led to his invention of the double diode, which became known as the Esaki diode. It also opened new possibilities for solid-state developments that his corecipients of the 1973 prize exploited separately. In 1960 Esaki was awarded an IBM (International Business Machines) fellowship for further research in the United States, and he subsequently joined IBM’s research laboratories in Yorktown, New York.

Esaki, who retained his Japanese citizenship, later returned to his home country. There he served as president of several institutions, including the University of Tsukuba (1992–98) and Yokohama College of Pharmacy (2006– ).

Details

Leo Esaki (born March 12, 1925) is a Japanese solid-state physicist who shared the 1973 Nobel Prize in Physics with Ivar Giaever and Brian Josephson for his work on tunneling in semiconductors, which led to his invention of the tunnel diode that exploits this phenomenon. His research was done when he was with Sony. He has also contributed in being a pioneer of the semiconductor superlattices.

Education and career

Leo Esaki was born on March 12, 1925, in Osaka, Japan, and grew up in Kyoto, where he attended the Third Higher School. He then went on to study physics at Tokyo Imperial University (now the University of Tokyo).

After graduating from UTokyo in 1947, Esaki joined the Kobe Kogyo company. In 1956, he became chief physicist at Tokyo Tsushin Kogyo (now Sony).

In 1960, Esaki moved to the United States and joined the IBM Thomas J. Watson Research Center, where he was appointed an IBM Fellow in 1967.

Research:

Tunnel diode

In 1957, Esaki recognized that when the p-n junction width of germanium is thinned, the current-voltage characteristic is dominated by the influence of the tunnel effect and, as a result, he discovered that as the voltage is increased, the current decreases inversely, indicating negative resistance. This discovery was the first demonstration of solid tunneling effects in physics, and it was the birth of a new electronic device called the tunnel diode (or Esaki diode), the first quantum electronic device in history. He received a Ph.D. from UTokyo due to this breakthrough invention in 1959.

In 1973, Esaki was awarded the Nobel Prize in Physics for this work. He became the first Nobel laureate to receive the prize from King Carl XVI Gustaf of Sweden.

Semiconductor superlattice

In 1969, Esaki predicted that semiconductor superlattices will be formed to induce a differential negative-resistance effect via an artificially one-dimensional periodic structural changes in semiconductor crystals. His unique "molecular beam epitaxy" thin-film crystal growth method can be regulated quite precisely in ultrahigh vacuum. His first paper on the semiconductor superlattice was published in 1970. A 1987 comment by Esaki regarding the original paper notes:

"The original version of the paper was rejected for publication by Physical Review on the referee's unimaginative assertion that it was 'too speculative' and involved 'no new physics.' However, this proposal was quickly accepted by the Army Research Office..."

In 1972, Esaki realized his concept of superlattices in III-V group semiconductors, later the concept influenced many fields like metals and magnetic materials. He was elected a member of the National Academy of Engineering for contributions to the engineering of semiconductor devices in 1977. He was also awarded the IEEE Medal of Honor "for contributions to and leadership in tunneling, semiconductor superlattices, and quantum wells" in 1991, and the Japan Prize "for the creation and realization of the concept of man-made superlattice crystals which lead to generation of new materials with useful applications" in 1998.

Later life

Esaki moved back to Japan in 1992. Subsequently, he served as president of the University of Tsukuba and Shibaura Institute of Technology. Since 2006, he is the president of Yokohama College of Pharmacy. Esaki is also the recipient of The International Center in New York's Award of Excellence, the Order of Culture (1974) and the Grand Cordon of the Order of the Rising Sun (1998).

Since the death of Yoichiro Nambu in 2015, Esaki is the oldest Japanese Nobel laureate.

Recognition

In recognition of three Nobel laureates' contributions, the bronze statues of Shin'ichirō Tomonaga, Leo Esaki, and Makoto Kobayashi were set up in the Central Park of Azuma 2 in Tsukuba City in 2015.

It appears to me that if one wants to make progress in mathematics, one should study the masters and not the pupils. - Niels Henrik Abel.

Nothing is better than reading and gaining more and more knowledge - Stephen William Hawking.

Offline

#1783 2025-09-25 21:13:32

- Jai Ganesh

- Administrator

- Registered: 2005-06-28

- Posts: 53,025

Re: crème de la crème

2346) Ivar Glaever

Gist:

Work

In quantum physics matter is described as both waves and particles. One result of this is the tunneling phenomenon, which means that particles can pass through barriers that they should not be able to squeeze through according to classic physics. In 1960 Ivar Giaever demonstrated a tunnel effect through a thin layer of oxide placed between metal in normal or superconducting conditions. Superconducting means that certain materials completely lack electrical resistance at low temperatures. Giaver’s discovery contributed to knowledge about the phenomenon in several ways.

Summary

Ivar Giaever (born April 5, 1929, Bergen, Norway—died June 20, 2025, Schenectady, New York, U.S.) was a Norwegian-born American physicist who shared the Nobel Prize for Physics in 1973 with Leo Esaki and Brian Josephson for work in solid-state physics.

Giaever received an engineering degree at the Norwegian Institute of Technology in Trondheim in 1952 and became a patent examiner for the Norwegian government. In 1954 he migrated to Canada, where he worked as a mechanical engineer with the General Electric Company in Ontario. In 1956 he was transferred to General Electric’s Development Center in Schenectady, New York. There he shifted his interest to physics and did graduate work at the Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute in Troy, New York, receiving a Ph.D. in 1964.

Giaever conducted most of his work in solid-state physics and particularly in superconductivity. He pursued the possible applications to superconductor technology of Esaki’s work in tunneling, eventually “marrying,” as he put it, the two concepts to produce superconductor devices that flouted previously accepted limitations and allowed electrons to pass like waves of radiation through “holes” in solid-state devices. Using a sandwich consisting of an insulated piece of superconducting metal and a normal one, he achieved new tunneling effects that led to greater understanding of superconductivity and that provided support for the BCS theory of superconductivity, for which John Bardeen (B), Leon Cooper (C), and John Robert Schrieffer (S) had won the Nobel Prize for Physics in 1972. It was for this work—based in part on Esaki’s and further developed by Josephson—that Giaever shared the 1973 Nobel Prize with Esaki and Josephson.

Details

Ivar Giaever (April 5, 1929 – June 20, 2025) was a Norwegian-American physicist who shared the 1973 Nobel Prize in Physics with Leo Esaki and Brian Josephson. One half of the prize was awarded jointly to Giaever and Esaki "for their experimental discoveries regarding tunneling phenomena in semiconductors and superconductors, respectively".

Education and career

Ivar Giaever was born on April 5, 1929, in Bergen, Norway. He studied mechanical engineering at the Norwegian Institute of Technology, and graduated in 1952. In 1954, he emigrated from Norway to Canada, where he was employed by the Canadian division of General Electric. He moved to the United States four years later, joining General Electric's Corporate Research and Development Center in Schenectady, New York, in 1958. He lived in Niskayuna, New York, since then, taking up US citizenship in 1964. While working for General Electric, Giaever earned a Ph.D. at the Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute in 1964. In 1988, he left General Electric to become a professor at the Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute. He also became a professor at the University of Oslo, sponsored by Statoil.

Giaever's research later in his career was mainly in the field of biophysics. In 1969, he studied biophysics for a year at the University of Cambridge through a Guggenheim Fellowship. He continued to work in this area after he returned to the US, founding the company Applied BioPhysics, Inc. in 1993.

The Nobel Prize