Math Is Fun Forum

You are not logged in.

- Topics: Active | Unanswered

#1801 2025-10-13 17:55:37

- Jai Ganesh

- Administrator

- Registered: 2005-06-28

- Posts: 52,126

Re: crème de la crème

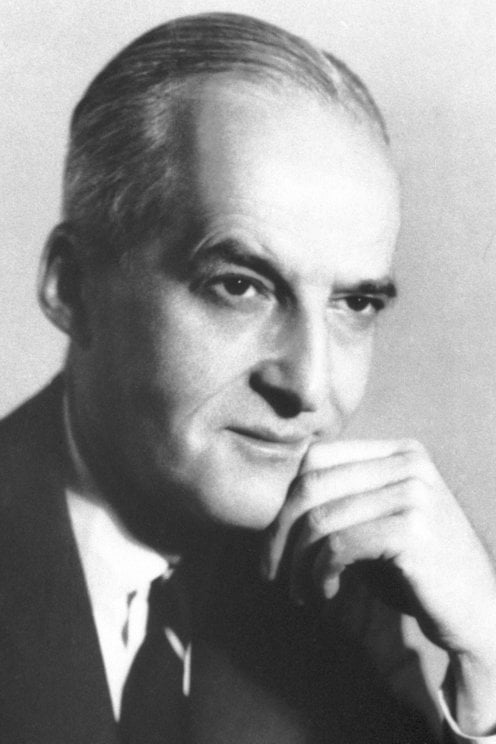

2364) Hannes Alfvén

Gist:

Work

The phenomenon of aurora borealis occurs when bursts of charged particles from the sun collide with the earth’s magnetic field. These jets of particles are an example of a special state of matter—plasma. Plasma is a gas comprised of electrons and ions (electrically charged atoms) that forms at high temperatures. From the late 1930s onward, Hannes Alfvén developed a theory about aurora borealis, which led to magneto-hydrodynamics; the theory of the relationships between a plasma’s movements, electric currents and fields, and magnetic fields.

Summary

Hannes Alfvén (born May 30, 1908, Norrköping, Sweden—died April 2, 1995, Djursholm) was an astrophysicist and winner, with Louis Néel of France, of the Nobel Prize for Physics in 1970 for his essential contributions in founding plasma physics—the study of plasmas (ionized gases).

Alfvén was educated at Uppsala University and in 1940 joined the staff of the Royal Institute of Technology, Stockholm. During the late 1930s and early ’40s he made remarkable contributions to space physics, including the theorem of frozen-in flux, according to which under certain conditions a plasma is bound to the magnetic lines of flux that pass through it. Alfvén later used the concept to explain the origin of cosmic rays.

In 1939 Alfvén published his theory of magnetic storms and auroral displays in the atmosphere, which immensely influenced the modern theory of the magnetosphere (the region of Earth’s magnetic field). He discovered a widely used mathematical approximation by which the complex spiral motion of a charged particle in a magnetic field can be easily calculated. Magnetohydrodynamics (MHD), the study of plasmas in magnetic fields, was largely pioneered by Alfvén, and his work has been acknowledged as fundamental to attempts to control nuclear fusion.

After numerous disagreements with the Swedish government, Alfvén obtained a position (1967) with the University of California, San Diego. Later he divided his teaching time between the Royal Institute of Technology in Stockholm and the University of California.

Alfvén devised “plasma cosmology,” a concept that challenged the big-bang model of the origin of the universe. The theory posited that the universe had no beginning (and has no foreseeable end) and that plasma—with its electric and magnetic forces—has done more to organize matter in the universe into star systems and other large observed structures than has the force of gravity. Much of Alfvén’s early research was included in his Cosmical Electrodynamics (1950). He also wrote On the Origin of the Solar System (1954), Worlds-Antiworlds (1966), and Cosmic Plasma (1981).

Details

Hannes Olof Gösta Alfvén (30 May 1908 – 2 April 1995) was a Swedish electrical engineer, plasma physicist and winner of the 1970 Nobel Prize in Physics for his work on magnetohydrodynamics (MHD). He described the class of MHD waves now known as Alfvén waves. He was originally trained as an electrical power engineer and later moved to research and teaching in the fields of plasma physics and electrical engineering. Alfvén made many contributions to plasma physics, including theories describing the behavior of aurorae, the Van Allen radiation belts, the effect of magnetic storms on the Earth's magnetic field, the terrestrial magnetosphere, and the dynamics of plasmas in the Milky Way galaxy.

Education

Alfvén received his PhD from the University of Uppsala in 1934. His thesis was titled "Investigations of High-frequency Electromagnetic Waves."

Early years

In 1934, Alfvén taught physics at both the University of Uppsala and the Nobel Institute for Physics (later renamed the Manne Siegbahn Institute of Physics) in Stockholm, Sweden. In 1940, he became professor of electromagnetic theory and electrical measurements at the Royal Institute of Technology in Stockholm. In 1945, he acquired the nonappointive position of Chair of Electronics. His title was changed to Chair of Plasma Physics in 1963. From 1954 to 1955, Alfvén was a Fulbright Scholar at the University of Maryland, College Park. In 1967, after leaving Sweden and spending time in the Soviet Union, he moved to the United States. Alfvén worked in the departments of electrical engineering at both the University of California, San Diego and the University of Southern California.

Later years

In 1991, Alfvén retired as professor of electrical engineering at the University of California, San Diego and professor of plasma physics at the Royal Institute of Technology in Stockholm.

Alfvén spent his later adult life alternating between California and Sweden. He died at the age of 86.

Personal life

Alfvén was married for 67 years to his wife Kerstin (1910–1992). They raised five children, one boy and four girls. Their son became a physician, while one daughter became a writer and another a lawyer in Sweden. The writer was Inger Alfvén and is well known for her work in Sweden. The composer Hugo Alfvén was Hannes Alfvén's uncle.

Alfvén studied the history of science, oriental philosophy, and religion. On his religious views, Alfven was irreligious and critical of religion. He spoke Swedish, English, German, French, and Russian, and some Spanish and Chinese. He expressed great concern about the difficulties of permanent high-level radioactive waste management." Alfvén was also interested in problems in cosmology and all aspects of auroral physics, and used Schröder's well known book on aurora, Das Phänomen des Polarlichts. Letters of Alfvén, Treder, and Schröder were published on the occasion of Treder's 70th birthday. The relationships between Hans-Jürgen Treder, Hannes Alfvén and Wilfried Schröder were discussed in detail by Schröder in his publications.

Alfvén died on 2 April, 1995 at Djursholm aged 86.

It appears to me that if one wants to make progress in mathematics, one should study the masters and not the pupils. - Niels Henrik Abel.

Nothing is better than reading and gaining more and more knowledge - Stephen William Hawking.

Offline

#1802 2025-10-15 18:13:16

- Jai Ganesh

- Administrator

- Registered: 2005-06-28

- Posts: 52,126

Re: crème de la crème

2365) Louis Néel

Gist:

Work

Magnetism takes different forms, some stemming from the magnetic moments of atoms of different materials. In ferromagnetic material the magnetic moments are oriented in the same direction. In 1932 Louis Néel described the antiferromagnetism phenomenon, where nearby magnetic moments in a material are oriented in opposite directions. In 1947 he also described the ferrimagnetism phenomenon, where the magnetic moments are aligned in opposite directions but of different magnitudes. The findings became an important factor in the development of computer memory and other applications.

Summary

Louis-Eugène-Félix Néel (born November 22, 1904, Lyon, France—died November 17, 2000, Brive-Corrèze) was a French physicist who was corecipient, with the Swedish astrophysicist Hannes Alfvén, of the Nobel Prize for Physics in 1970 for his pioneering studies of the magnetic properties of solids. His contributions to solid-state physics have found numerous useful applications, particularly in the development of improved computer memory units.

Néel attended the École Normale Supérieure in Paris and the University of Strasbourg (Ph.D., 1932), where he studied under Pierre-Ernest Weiss and first began researching magnetism. He was a professor at the universities of Strasbourg (1937–45) and Grenoble (1945–76), and in 1956 he founded the Center for Nuclear Studies in Grenoble, serving as its director until 1971. Néel also was director (1971–76) of the Polytechnic Institute in Grenoble.

During the early 1930s Néel studied, on the molecular level, forms of magnetism that differ from ferromagnetism. In ferromagnetism, the most common variety of magnetism, the electrons line up (or spin) in the same direction at low temperatures. He discovered that, in some substances, alternating groups of atoms align their electrons in opposite directions (much as when two identical magnets are placed together with opposite poles aligned), thus neutralizing the net magnetic effect. This magnetic property is called antiferromagnetism. Néel’s studies of fine-grain ferromagnetics provided an explanation for the unusual magnetic memory of certain mineral deposits that has provided information on changes in the direction and strength of the Earth’s magnetic field.

Néel wrote more than 200 works on various aspects of magnetism. Mainly because of his contributions, ferromagnetic materials can be manufactured to almost any specifications for technical applications, and a flood of new synthetic ferrite materials has revolutionized microwave electronics.

Details

Louis Eugène Félix Néel (22 November 1904 – 17 November 2000) was a French physicist born in Lyon who received the Nobel Prize for Physics in 1970 for his studies of the magnetic properties of solids.

Biography

Néel studied at the Lycée du Parc in Lyon and was accepted at the École Normale Supérieure in Paris. He obtained the degree of Doctor of Science at the University of Strasbourg. He was corecipient (with the Swedish astrophysicist Hannes Alfvén) of the Nobel Prize for Physics in 1970 for his pioneering studies of the magnetic properties of solids. His contributions to solid state physics have found numerous useful applications, particularly in the development of improved computer memory units. About 1930 he suggested that a new form of magnetic behavior might exist; called antiferromagnetism, as opposed to ferromagnetism. Above a certain temperature (the Néel temperature) this behaviour stops. Néel pointed out (1948) that materials could also exist showing ferrimagnetism. Néel has also given an explanation of the weak magnetism of certain rocks, making possible the study of the history of Earth's magnetic field.

He is the instigator of the Polygone Scientifique in Grenoble.

The Louis Néel Medal, awarded annually by the European Geophysical Society, is named in Néel's honour.

Néel died at Brive-la-Gaillarde on 17 November 2000 at the age 95, just 5 days short of his 96th birthday.

It appears to me that if one wants to make progress in mathematics, one should study the masters and not the pupils. - Niels Henrik Abel.

Nothing is better than reading and gaining more and more knowledge - Stephen William Hawking.

Offline

#1803 Yesterday 17:29:43

- Jai Ganesh

- Administrator

- Registered: 2005-06-28

- Posts: 52,126

Re: crème de la crème

2366) Luis Federico Leloir

Gist:

Work

Carbohydrates, including sugars and starches, are of paramount importance to the life processes of organisms. Luis Leloir demonstrated that nucleotides—molecules that also constitute the building blocks of DNA molecules—are crucial when carbohydrates are generated and converted. In 1949 Leloir discovered that one type of sugar’s conversion to another depends on a molecule that consists of a nucleotide and a type of sugar. He later showed that the generation of carbohydrates is not an inversion of metabolism, as had been assumed previously, but processes with other steps.

Summary

Luis Federico Leloir (born Sept. 6, 1906, Paris, France—died Dec. 2, 1987, Buenos Aires, Arg.) was an Argentine biochemist who won the Nobel Prize for Chemistry in 1970 for his investigations of the processes by which carbohydrates are converted into energy in the body.

After serving as an assistant at the Institute of Physiology, University of Buenos Aires, from 1934 to 1935, Leloir worked a year at the biochemical laboratory at the University of Cambridge and in 1937 returned to the Institute of Physiology, where he undertook investigations of the oxidation of fatty acids. In 1947 he obtained financial support to set up the Institute for Biochemical Research, Buenos Aires, where he began research on the formation and breakdown of lactose, or milk sugar, in the body. That work ultimately led to his discovery of sugar nucleotides, which are key elements in the processes by which sugars stored in the body are converted into energy. He also investigated the formation and utilization of glycogen and discovered certain liver enzymes that are involved in its synthesis from glucose.

Details

Luis Federico Leloir (September 6, 1906 – December 2, 1987) was an Argentine physician and biochemist who received the 1970 Nobel Prize in Chemistry for his discovery of the metabolic pathways by which carbohydrates are synthesized and converted into energy in the body. Although born in France, Leloir received the majority of his education at the University of Buenos Aires and was director of the private research group Fundación Instituto Campomar until his death in 1987. His research into sugar nucleotides, carbohydrate metabolism, and renal hypertension garnered international attention and led to significant progress in understanding, diagnosing and treating the congenital disease galactosemia. Leloir is buried in La Recoleta Cemetery, Buenos Aires.

Biography:

Early years

Leloir's parents, Federico Augusto Rufino and Hortencia Aguirre de Leloir, traveled from Buenos Aires to Paris in the middle of 1906 with the intention of treating Federico's illness. However, Federico died in late August, and a week later Luis was born in an old house at 81 Víctor Hugo Road in Paris, a few blocks away from the Arc de Triomphe. After returning to Argentina in 1908, Leloir lived together with his eight siblings on their family's extensive property El Tuyú that his grandparents had purchased after their immigration from the Basque Country of northern Spain: El Tuyú comprises 400 {km}^{2} of sandy land along the coastline from San Clemente del Tuyú to Mar de Ajó which has since become a popular tourist attraction.

During his childhood, the future Nobel Prize winner found himself observing natural phenomena with particular interest; his schoolwork and readings highlighted the connections between the natural sciences and biology. His education was divided between Escuela General San Martín (primary school), Colegio Lacordaire (secondary school), and for a few months at Beaumont College in England. His grades were unspectacular, and his first stint in college ended quickly when he abandoned his architectural studies that he had begun in Paris' École Polytechnique.

It was during the 1920s that Leloir invented salsa golf (golf sauce). After being served prawns with the usual sauce during lunch with a group of friends at the Ocean Club in Mar del Plata, Leloir came up with a peculiar combination of ketchup and mayonnaise to spice up his meal. With the financial difficulties that later plagued Leloir's laboratories and research, he would joke, "If I had patented that sauce, we'd have a lot more money for research right now.

Nobel Prize

On December 2, 1970, Leloir received the Nobel Prize for Chemistry from the King of Sweden for his discovery of the metabolic pathways in lactose, becoming only the third Argentine to receive the prestigious honor in any field at the time. In his acceptance speech at Stockholm, he borrowed from Winston Churchill's famous 1940 speech to the House of Commons and remarked, "never have I received so much for so little". Leloir and his team reportedly celebrated by drinking champagne from test tubes, a rare departure from the humility and frugality that characterized the atmosphere of Fundación Instituto Campomar under Leloir's direction. The $80,000 prize money was spent directly on research, and when asked about the significance of his achievement, Leloir responded:

"This is only one step in a much larger project. I discovered (no, not me: my team) the function of sugar nucleotides in cell metabolism. I want others to understand this, but it is not easy to explain: this is not a very noteworthy deed, and we hardly know even a little."

It appears to me that if one wants to make progress in mathematics, one should study the masters and not the pupils. - Niels Henrik Abel.

Nothing is better than reading and gaining more and more knowledge - Stephen William Hawking.

Offline