Math Is Fun Forum

You are not logged in.

- Topics: Active | Unanswered

#2651 2025-11-19 16:39:14

- Jai Ganesh

- Administrator

- Registered: 2005-06-28

- Posts: 53,507

Re: Miscellany

2451) Ozone

Gist

Ozone (O3) is a gas with a distinct odor that exists in two layers of the atmosphere: the protective stratospheric ozone layer and the harmful ground-level ozone. While stratospheric ozone is beneficial because it shields the Earth from the sun's harmful ultraviolet (UV) radiation, ground-level ozone is a major air pollutant and a key component of smog that can cause serious health problems. Ground-level ozone forms when pollutants from sources like car exhaust and industrial emissions react with sunlight.

Ozone (O3) is a gas with a chemical formula of O3, meaning it has three oxygen atoms instead of the two in the oxygen we breathe (O2). It can be "good" or "bad" depending on its location in the atmosphere: "good" stratospheric ozone forms a protective layer that shields Earth from the sun's harmful ultraviolet (UV) radiation, while "bad" ground-level ozone is a pollutant that can damage lungs and crops.

Summary

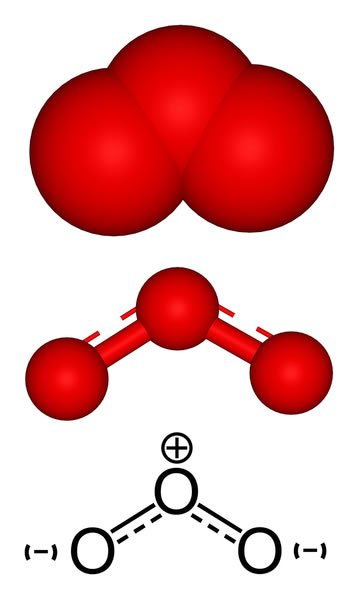

Ozone, also called trioxygen, is an inorganic molecule with the chemical formula O3. It is a pale-blue gas with a distinctively pungent odour. It is an allotrope of oxygen that is much less stable than the diatomic allotrope O2, breaking down in the lower atmosphere to O2 (dioxygen). Ozone is formed from dioxygen by the action of ultraviolet (UV) light and electrical discharges within the Earth's atmosphere. It is present in very low concentrations throughout the atmosphere, with its highest concentration high in the ozone layer of the stratosphere, which absorbs most of the Sun's ultraviolet (UV) radiation.

Ozone's odour is reminiscent of chlorine, and detectable by many people at concentrations of as little as 0.1 ppm in air. Ozone's O3 structure was determined in 1865. The molecule was later proven to have a bent structure and to be weakly diamagnetic. At standard temperature and pressure, ozone is a pale blue gas that condenses at cryogenic temperatures to a dark blue liquid and finally a violet-black solid. Ozone's instability with regard to more common dioxygen is such that both concentrated gas and liquid ozone may decompose explosively at elevated temperatures, physical shock, or fast warming to the boiling point. It is therefore used commercially only in low concentrations.

Ozone is a powerful oxidising agent (far more so than dioxygen) and has many industrial and consumer applications related to oxidation. This same high oxidising potential, however, causes ozone to damage mucous and respiratory tissues in animals, and also tissues in plants, above concentrations of about 0.1 ppm. While this makes ozone a potent respiratory hazard and pollutant near ground level, a higher concentration in the ozone layer (from two to eight ppm) is beneficial, preventing damaging UV light from reaching the Earth's surface.

Details

Ozone, (O3), triatomic allotrope of oxygen (a form of oxygen in which the molecule contains three atoms instead of two as in the common form) that accounts for the distinctive odor of the air after a thunderstorm or around electrical equipment. The odor of ozone around electrical machines was reported as early as 1785; ozone’s chemical constitution was established in 1872. Ozone is an irritating pale blue gas that is explosive and toxic, even at low concentrations. It occurs naturally in small amounts in Earth’s stratosphere, where it absorbs solar ultraviolet radiation, which otherwise could cause severe damage to living organisms on Earth’s surface. Under certain conditions, photochemical reactions between nitrogen oxides and hydrocarbons in the lower atmosphere can produce ozone in concentrations high enough to cause irritation of the eyes and mucous membranes. Such ground-level ozone is considered a major air pollutant.

Ozone usually is manufactured by passing an electric discharge through a current of oxygen or dry air. The resulting mixtures of ozone and original gases are suitable for most industrial purposes, although purer ozone may be obtained from them by various methods; for example, upon liquefaction, an oxygen-ozone mixture separates into two layers, of which the denser one contains about 75 percent ozone. The extreme instability and reactivity of concentrated ozone makes its preparation both difficult and hazardous.

Ozone is 1.5 times as dense as oxygen; at −112 °C (−170 °F) it condenses to a dark blue liquid, which freezes at −251.4 °C (−420 °F). The gas decomposes rapidly at temperatures above 100 °C (212 °F) or, in the presence of certain catalysts, at room temperatures. Although it resembles oxygen in many respects, ozone is much more reactive; hence, it is an extremely powerful oxidizing agent, particularly useful in converting olefins into aldehydes, ketones, or carboxylic acids. Because it can decolorize many substances, it is used commercially as a bleaching agent for organic compounds; as a strong germicide it is used to sterilize drinking water as well as to remove objectionable odors and flavors.

Additional Information

Ozone (O3) is a highly reactive gas composed of three oxygen atoms. It is both a natural and a man-made product that occurs in the Earth's upper atmosphere (the stratosphere) and lower atmosphere (the troposphere). Depending on where it is in the atmosphere, ozone affects life on Earth in either good or bad ways.

Stratospheric ozone is formed naturally through the interaction of solar ultraviolet (UV) radiation with molecular oxygen (O2). The "ozone layer," approximately 6 through 30 miles above the Earth's surface, reduces the amount of harmful UV radiation reaching the Earth's surface.

Tropospheric or ground-level ozone – what we breathe – is formed primarily from photochemical reactions between two major classes of air pollutants, volatile organic compounds (VOC) and nitrogen oxides (NOx). These reactions have traditionally been viewed as depending upon the presence of heat and sunlight, resulting in higher ambient ozone concentrations in summer months. Within the last decade, however, high ozone concentrations have also been observed under specific circumstances in cold months, where a few high elevation areas in the Western U.S. with high levels of local VOC and NOx emissions have formed ozone when snow is on the ground and temperatures are near or below freezing. Ozone contributes to what we typically experience as "smog" or haze, which still occurs most frequently in the summertime, but can occur throughout the year in some southern and mountain regions.

Although some stratospheric ozone is transported into the troposphere, and some VOC and NOx occur naturally, the majority of ground-level ozone is the result of reactions of man-made VOC and NOx. Significant sources of VOC are chemical plants, gasoline pumps, oil-based paints, autobody shops, and print shops. Nitrogen oxides result primarily from high temperature combustion. Significant sources are power plants, industrial furnaces and boilers, and motor vehicles.

Ozone has two properties of interest to human health. First, it absorbs UV light, reducing human exposure to harmful UV radiation that causes skin cancer and cataracts. Second, when inhaled, it reacts chemically with many biological molecules in the respiratory tract, leading to a number of adverse health effects. This course addresses this second property.

Ozone (O3) is a gas molecule composed of three oxygen atoms which occur both in the Earth's upper atmosphere and at ground level. There is both a "good" and "bad" Ozone.

Bad Ozone - Ground-level Ozone is an air pollutant that is harmful to breathe and damages crops, trees, and other vegetation. It is the main ingredient of urban smog. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) states that breathing ground-level ozone can be harmful to your health.

Good Ozone - Ozone is produced naturally in the stratosphere. But this "good" ozone layer is gradually being destroyed by man-made chemicals referred to as ozone-depleting substances (ODS). Essentially, Ozone is only good for our stratosphere, which is a layer of the earth's protective barrier.

It appears to me that if one wants to make progress in mathematics, one should study the masters and not the pupils. - Niels Henrik Abel.

Nothing is better than reading and gaining more and more knowledge - Stephen William Hawking.

Offline

#2652 2025-11-27 22:27:18

- Jai Ganesh

- Administrator

- Registered: 2005-06-28

- Posts: 53,507

Re: Miscellany

2452) Seebeck Effect

Gist

Seebeck effect, production of an electromotive force (emf) and consequently an electric current in a loop of material consisting of at least two dissimilar conductors when two junctions are maintained at different temperatures. The conductors are commonly metals, though they need not even be solids. The German physicist Thomas Johann Seebeck discovered (1821) the effect. The Seebeck effect is used to measure temperature with great sensitivity and accuracy and to generate electric power for special applications.

Summary

The Seebeck effect is the direct conversion of temperature differences into electrical voltage, generated when two different conductors or semiconductors are joined to form a loop. This phenomenon creates a small voltage, called the Seebeck voltage, which can be used for practical applications like generating electricity from heat using thermoelectric generators or measuring temperature with thermocouples.

The Seebeck effect is the phenomenon where a temperature difference between two different conductors or semiconductors creates an electrical voltage. This direct conversion of thermal energy to electrical energy is the principle behind thermoelectric devices like thermocouples, which use a temperature gradient to generate a measurable voltage.

Details:

Key learnings:

Seebeck Effect Definition: The Seebeck effect is defined as the conversion of temperature differences into electric voltage, enabling various practical applications.

Temperature to Electricity: This effect generates electricity when there is a temperature difference across the junctions of two different materials.

Key Applications: Thermocouples and thermoelectric generators are primary applications, used for temperature measurement and converting waste heat into power.

Material Requirements: Effective materials for the Seebeck effect include metals with low Seebeck coefficients and semiconductors with higher coefficients for better performance.

Advantages and Challenges: While the Seebeck effect is reliable and can harness low-grade heat, finding materials with the right properties remains a significant challenge.

The Seebeck effect is a phenomenon that converts temperature differences into electric voltage and vice versa. It is named after Thomas Johann Seebeck, a German physicist who discovered it in 1821. The Seebeck effect is the basis of thermocouples, thermoelectric generators, and spin caloritronics.

Thomas Seebeck:

What is the Seebeck Effect?

The Seebeck effect is defined as the generation of an electric potential (or voltage) across two different conductors or semiconductors that are connected in a loop and have a temperature difference between their junctions. The voltage is proportional to the temperature difference and depends on the materials used.

For example, a thermocouple is a device that uses the Seebeck effect to measure temperature. It consists of two wires made of different metals (such as copper and iron) that are joined at both ends. One end is exposed to a hot source (such as a flame) and the other end is kept cold (such as in ice water). The temperature difference between the ends creates a voltage across the wires, which can be measured by a voltmeter.

The Seebeck effect also enables the generation of electricity from waste heat. In a thermoelectric generator, multiple thermocouples are linked either in series or parallel. These thermocouples have one side connected to a heat source—like an engine or furnace—and the other to a heat sink, such as air or water. This temperature differential generates a voltage capable of powering electrical devices, such as lights or fans.

How Does the Seebeck Effect Work?

Electrons, which are negatively charged and move freely in conductors and semiconductors, drive the Seebeck effect. When these materials are heated, the electrons gain energy and move from the hot area to the cooler one, generating an electric current as they travel.

However, different materials have different numbers and types of electrons available for conduction. Some materials have more electrons than others, and some have electrons with different spin orientations. Spin is a quantum property of electrons that makes them act like tiny magnets. When two materials with different electron characteristics are joined together, they form an interface where electrons can exchange energy and spin.

The Seebeck effect occurs when two such interfaces are subjected to a temperature difference. The electrons at the hot interface gain more energy and spin from the heat source and transfer them to the electrons at the cold interface through the loop. This creates an imbalance of charge and spin between the interfaces, resulting in an electric potential and a magnetic field. The electric potential drives an electric current through the loop, while the magnetic field deflects a compass needle placed near it.

What are the Applications of the Seebeck Effect?

The Seebeck effect has many applications in science, engineering, and technology. Some of them are:

* Thermocouples: These are devices that use the Seebeck effect to measure temperature with high accuracy and sensitivity. They are widely used in industries, laboratories, and households for various purposes, such as controlling ovens, monitoring engines, measuring body temperature, etc.

* Thermoelectric generators: These are devices that use the Seebeck effect to convert waste heat into electricity for special applications, such as powering spacecraft, remote sensors, medical implants, etc.

* Spin caloritronics: This is a branch of physics that studies how heat and spin interact in magnetic materials. The Seebeck effect plays an important role in this field, as it can create spin currents and voltages from temperature gradients. This can lead to novel devices for information processing and storage, such as spin batteries, spin transistors, spin valves, etc.

What are the Advantages and Limitations of the Seebeck Effect?

The Seebeck effect has some advantages and limitations that affect its performance and efficiency. Some of them are:

Advantages: The Seebeck effect is simple, reliable, and versatile. It does not require any moving parts or external power sources. It can operate over a wide range of temperatures and materials. It can generate electricity from low-grade heat sources that would otherwise be wasted.

Limitations: The Seebeck effect is limited by the availability and compatibility of materials. It requires materials with high electrical conductivity and low thermal conductivity to achieve high voltage and low heat loss. It also requires materials with different Seebeck coefficients to create a voltage difference. The Seebeck coefficient is a property that measures how much voltage is generated per unit temperature difference for a given material. The Seebeck coefficient depends on the type and concentration of charge carriers, their energy levels, and their interactions with the lattice. The Seebeck coefficient can vary with temperature, composition, and magnetic field. Finding materials with high and stable Seebeck coefficients is a challenge for thermoelectric applications.

What are the Types of Materials Used for the Seebeck Effect?

The materials used for the Seebeck effect can be classified into three categories: metals, semiconductors, and superconductors.

* Metals: Metals are good conductors of both electricity and heat. They have low Seebeck coefficients and high thermal conductivity, which makes them inefficient for thermoelectric applications. However, metals are easy to fabricate and connect, and they have high mechanical strength and stability. Metals are commonly used for thermocouples, where accuracy and durability are more important than efficiency. Some examples of metal pairs used for thermocouples are copper-constantan, iron-constantan, chromel-alumel, etc.

* Semiconductors: Semiconductors are materials that have an intermediate electrical conductivity that can be controlled by doping or applying an electric field. They have higher Seebeck coefficients and lower thermal conductivity than metals, which makes them more suitable for thermoelectric applications. However, semiconductors are more difficult to fabricate and connect, and they have lower mechanical strength and stability than metals. Semiconductors are commonly used for thermoelectric generators and coolers, where efficiency and performance are more important than accuracy and durability. Some examples of semiconductor pairs used for thermoelectric devices are bismuth telluride-antimony telluride, lead telluride-silicon germanium, etc.

* Superconductors: Superconductors are materials that have zero electrical resistance below a critical temperature. They have very high Seebeck coefficients and very low thermal conductivity, which makes them ideal for thermoelectric applications. However, superconductors are very rare and expensive, and they require very low temperatures to operate, which limits their practical use. Superconductors are mainly used for research purposes, such as studying the spin Seebeck effect, which is a phenomenon that involves the generation of a spin voltage from a temperature gradient in a magnetic material.

Conclusion

The Seebeck effect, which transforms temperature differences into electrical voltage, plays a crucial role in devices like thermocouples and thermoelectric generators. Its efficiency hinges on the materials used—specifically their conductivity and Seebeck coefficients. Despite challenges in material selection, its potential in various fields remains substantial.

Additional Information

The Seebeck effect is a phenomenon in which a temperature difference between two dissimilar electrical conductors or semiconductors produces a voltage difference between the two substances.

When heat is applied to one of the two conductors or semiconductors, heated electrons flow toward the cooler conductor or semiconductor. If the pair is connected through an electrical circuit, direct current (DC) flows through that circuit.

Seebeck effect: Key findings

The Seebeck effect refers to the buildup of electric potential which happens when there is a temperature gradient between different electrical conductors or semiconductors.

Here are some key findings of this phenomenon:

* The voltages produced by the Seebeck effect are small, usually only a few microvolts (millionths of a volt) per kelvin of temperature difference at the junction between the conductors or semiconductors.

* If the temperature difference is large enough, some Seebeck-effect devices can produce a few millivolts (thousandths of a volt).

* Numerous such devices can be connected in series to increase the output voltage or in parallel to increase the maximum deliverable current.

* Large arrays of Seebeck-effect devices can provide useful, small-scale electrical power if a large temperature difference is maintained across the junctions.

Seebeck effect: Explanation

In 1821, German physicist Thomas Seebeck discovered that when two wires made from dissimilar metals are joined at two ends to form a loop, and if the two junctions are maintained at different temperatures, a voltage develops in the circuit. This phenomenon is therefore named after him.

When heat is applied to one of the two conductors or semiconductors, that metal heats up. Consequently, the valence electrons present in this metal flow toward the cooler metal. This happens because electrons move to where energy (in this case, heat) is lower. If the metals are connected through an electrical circuit, direct current flows through the circuit.

However, this voltage is just a few microvolts per kelvin temperature difference. Thermal energy is continuously transferred from the warmer metal to the cooler metal until eventually, temperature equilibrium is obtained.

The Seebeck effect and its resultant thermoelectric effect is a reversible process. If the hot and cold junctions are interchanged, valence electrons will flow in the other direction, and also change the direction of the DC current.

Seebeck effect and thermocouples

The pair of metal wires forming the electrical circuit is known as a thermocouple. On a larger scale and due to the Seebeck effect, thermocouples are used to approximately measure temperature differences. They are also used to actuate electronic switches that can turn large systems on and off, a capability that is employed in thermoelectric cooling technology.

Seebeck used copper and bismuth in his experiment. Other common thermocouple metal combinations that are used today include the following:

* constantan and copper

* constantan and iron

* constantan and chromel

* constantan and alumel

Applications of Seebeck effect

There are many applications of the Seebeck effect. In addition to its use in thermocouples to measure temperature differences, the phenomenon is also used in the following ways:

* in thermopiles (that is, in a setting where a number of thermocouples are connected in series);

* in thermoelectric generators that function as heat engines;

* in power plants to convert waste heat into (extra) power;

* in automobiles as automotive thermoelectric generators, to increase fuel efficiency;

* in high-frequency electrical power sensors;

* to verify material degradation and radiation level, and to perform strength testing of radioactive materials (which vary with temperature over a given time period); and

* to actuate security alarms or switches.

Spin Seebeck effect

In 2008, physicists discovered the Spin Seebeck effect (SSE). This effect refers to the generation of a spin voltage caused by a temperature gradient in a ferromagnet. This gradient enables the thermal injection of spin currents from the ferromagnet into a nonmagnetic metal. This injection happens over a macroscopic scale of several millimeters.

SSE is seen when heat is applied to a magnetized metal. As a result, electrons rearrange themselves according to their spin. Unlike ordinary electron movement, this rearrangement does not create heat as a waste product.

The effect could lead to the development of smaller, faster and more energy-efficient microchips or switches, as well as spintronics devices.

Seebeck effect vs. Peltier effect

In 1834, Jean Peltier, a French watchmaker, discovered another second thermoelectric effect that was later named the Peltier effect. Peltier observed that when a current flows through a circuit containing a junction of two dissimilar metals -- similar to the setup in the Seebeck effect -- heat is either absorbed or liberated at the junction. This absorption or liberation depends on the pair of metals used and the direction of the current.

The Seebeck effect and Peltier effect both involve circuits made from dissimilar metals, as well as heat and electricity. Both are also reversible processes. But despite these similarities, there are some differences between these effects as well.

The Seebeck effect occurs when the two ends of a thermocouple are at different temperatures, which results in electricity flowing from the hot metal to the cold metal.

In the Peltier effect, a temperature difference is created between the junctions when electrical current flows across the terminals. In a copper-constantan thermocouple in which the current at the junction is flowing from copper (+) to constantan (-), heat will be absorbed. But if the direction of the current is reversed -- i.e., from constantan (-) to copper (+) -- it will result in heat liberation.

It appears to me that if one wants to make progress in mathematics, one should study the masters and not the pupils. - Niels Henrik Abel.

Nothing is better than reading and gaining more and more knowledge - Stephen William Hawking.

Offline

#2653 2025-12-03 14:05:57

- Jai Ganesh

- Administrator

- Registered: 2005-06-28

- Posts: 53,507

Re: Miscellany

2453) Parsec

Gist

A parsec is a unit of distance used in astronomy, equivalent to approximately 3.26 light-years. It is defined as the distance at which one astronomical unit (the average distance between the Earth and the Sun) subtends an angle of one arcsecond.

A parsec can be defined as the length of the right triangle side adjacent to the vertex occupied by a star whose parallax angle is one arcsecond.

Summary

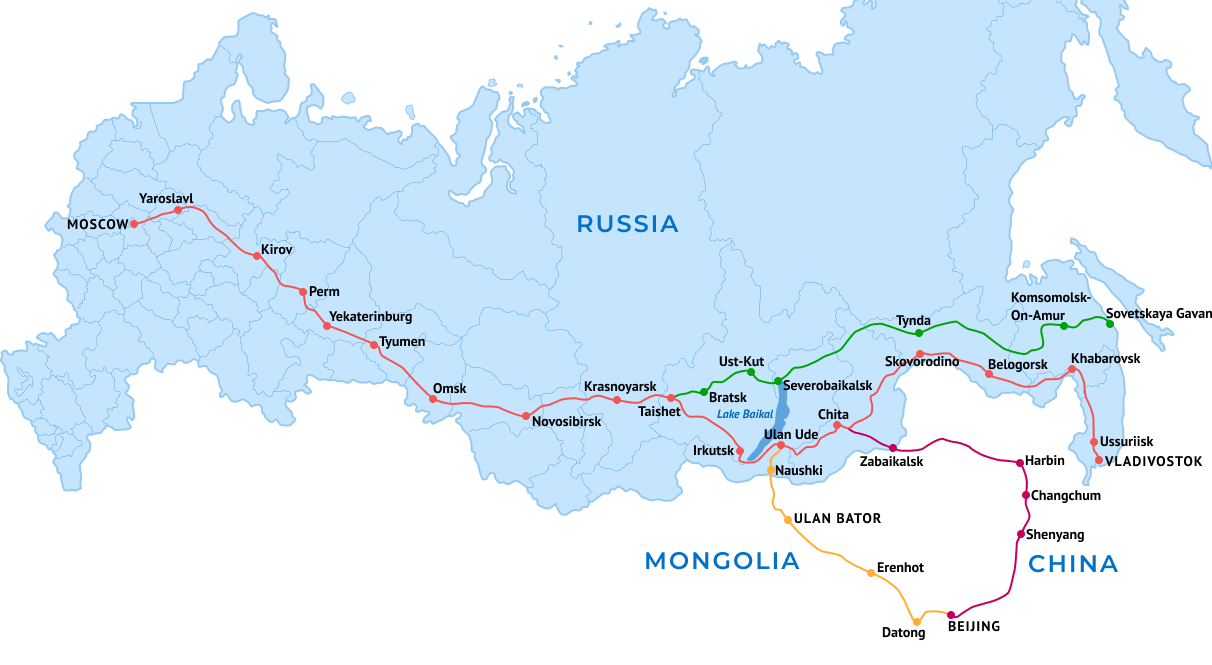

The parsec (symbol: pc) is a unit of length used to measure the large distances to astronomical objects outside the Solar System, approximately equal to 3.26 light-years or 206,265 astronomical units (AU), i.e. 30.9 trillion kilometres (19.2 trillion miles).[a] The parsec unit is obtained by the use of parallax and trigonometry, and is defined as the distance at which 1 AU subtends an angle of one arcsecond (1/3600 of a degree). The nearest star, Proxima Centauri, is about 1.3 parsecs (4.2 light-years) from the Sun: from that distance, the gap between the Earth and the Sun spans slightly less than one arcsecond. Most stars visible to the naked eye are within a few hundred parsecs of the Sun, with the most distant at a few thousand parsecs, and the Andromeda Galaxy at over 700,000 parsecs.

The word parsec is a shortened form of a distance corresponding to a parallax of one second, coined by the British astronomer Herbert Hall Turner in 1913. The unit was introduced to simplify the calculation of astronomical distances from raw observational data. Partly for this reason, it is the unit preferred in astronomy and astrophysics, though in popular science texts and common usage the light-year remains prominent. Although parsecs are used for the shorter distances within the Milky Way, multiples of parsecs are required for the larger scales in the universe, including kiloparsecs (kpc) for the more distant objects within and around the Milky Way, megaparsecs (Mpc) for mid-distance galaxies, and gigaparsecs (Gpc) for many quasars and the most distant galaxies.

In August 2015, the International Astronomical Union (IAU) passed Resolution B2 which, as part of the definition of a standardized absolute and apparent bolometric magnitude scale, mentioned an existing explicit definition of the parsec as exactly 648000/{pi} au, or approximately 30856775814913673 metres, given the IAU 2012 exact definition of the astronomical unit in metres. This corresponds to the small-angle definition of the parsec found in many astronomical references.

Details

A parsec is a unit for expressing distances to stars and galaxies, used by professional astronomers. It represents the distance at which the radius of Earth’s orbit subtends an angle of one second of arc. Thus, a star at a distance of one parsec would have a parallax of one second, and the distance of an object in parsecs is the reciprocal of its parallax in seconds of arc. For example, the nearest star, Proxima Centauri, which is part of the Alpha Centauri triple-star system, has a parallax of 0.769 second of arc, and, hence, its distance from the Sun and Earth is 1.30 parsec. One parsec equals 3.26 light-years, which is equivalent to 3.09 × {10}^{13} km (1.92 × {10}^{13} miles).

In the Milky Way Galaxy, wherein Earth is located, distances to remote stars are measured in terms of kiloparsecs (1 kiloparsec = 1,000 parsecs). The Sun is at a distance of 8.3 kiloparsecs from the centre of the Milky Way system. When dealing with other galaxies or clusters of galaxies, the convenient unit is the megaparsec (1 megaparsec = 1,000,000 parsecs). The distance to the Andromeda Galaxy (Messier 31) is about 0.76 megaparsec. The farthest galaxies and quasars have distances on the order of about 4,000 megaparsecs, or 13,000,000,000 light-years.

Additional Information

If you ever heard professional astronomers talking among themselves, you wouldn’t hear much talk of light-years. The concept of a light-year – the distance light travels in a single earthly year, or about 6 trillion miles (nearly 10 trillion km) – is a great way to think about distance scales in the universe. But light-years aren’t as useful as parsecs when it comes to measuring those distances. A parsec – a unit of distance equal to about 19 trillion miles (more than 30 trillion km) – is more closely related to how astronomers go about the business of figuring out the size of the universe.

To find the distance to a nearby star, astronomers use triangulation. You can try it for yourself, right now. Hold your finger in front of your face, focus on something in the distance, and close first one eye, then the other eye. As you alternate eyes, you’ll notice your finger appears to dance back and forth in front of your face. The motion is, of course, an illusion. Your finger isn’t moving. Each eye sees your finger from a slightly different angle. So the finger’s location, relative to stuff in the background, looks different. This apparent shift is called parallax, from a Greek word meaning alternation.

These angles are miniscule. They’re too small for degrees to be a practical unit of measurement. That’s why parallax angles are typically measured in arcseconds – a unit of measurement equivalent to the width of an average human hair seen from 65 feet (20 meters) away – not degrees. There are 3,600 arcseconds in one degree.

And here’s how we arrive at parsecs as a unit of distance: one parsec is the distance to an object whose parallax angle is one arcsecond.

The term parsec is just over 100 years old. It first appeared in a 1913 paper by English astronomer Sir Frank Watson Dyson, and the term stuck. If you see a star with 1/2 arcsecond of parallax, it is two parsecs away. At 1/3 arcsecond, it is three parsecs away. And so on.

Basically, astronomers liked it because it made the math easier!

One parsec is approximately 19 trillion miles (30 trillion km). That’s a bit over three light-years. The Voyager 1 probe, launched in 1977, is the most distant manmade object from Earth. It is a mere six ten-thousandths of a parsec away. The nearest star to the sun, a small red dwarf named Proxima Centauri, is just over one parsec from us.

That is actually fairly typical in our neck of the galaxy – one star for every cubic parsec – but it’s not typical everywhere. In the cores of globular clusters, the density can reach well over a hundred stars per cubic parsec!

The center of the galaxy lies just over 8,000 parsecs from us in the direction of the constellation Sagittarius.

The Andromeda Galaxy, the closest spiral galaxy to our own, is nearly 800 kiloparsecs away. A kiloparsec is one thousand parsecs.

At larger scales, astronomers start to talk of megaparsecs and even gigaparsecs. That’s one million and one billion parsecs, respectively. These are generally reserved for the largest structures in existence. The Virgo Cluster, a conglomeration of thousands of galaxies towards which our own Local Group is falling, lies 16 megaparsecs from home. It would take 54 million years to reach it traveling at the speed of light.

It appears to me that if one wants to make progress in mathematics, one should study the masters and not the pupils. - Niels Henrik Abel.

Nothing is better than reading and gaining more and more knowledge - Stephen William Hawking.

Offline

#2654 2025-12-04 17:31:01

- Jai Ganesh

- Administrator

- Registered: 2005-06-28

- Posts: 53,507

Re: Miscellany

2454) Electric Bell

Gist

An electric bell is a device that uses an electromagnet to create a repetitive ringing sound. When the switch is pressed, an electric current flows, making the electromagnet attract an armature with a hammer. The hammer strikes the bell, but this action breaks the circuit, deactivates the electromagnet, and allows a spring to pull the armature back. The circuit is re-established, and the cycle repeats until the switch is released.

Principle: The electric bell works on the principle of electromagnetism — when an electric current flows through a coil, it behaves like a magnet and attracts a piece of iron. Working: When the switch is pressed, current flows through the electromagnet. The electromagnet pulls the iron armature towards it.

Summary

The electric bell contains an electromagnet, consisting of coils of insulated wire wound around iron rods. When an electric current flows through the coils, the rods become magnetic and attract a piece of iron attached to a clapper. The clapper hits the bell and makes it ring.

Working of an electric bell

Electric current flows through the coil when the switch is ON, and the iron core acts as an electromagnet. The iron core attracts the hammer towards it. The hammer hits the bell and produces a sound. The circuit breaks at the screw contact when the hammer moves towards the iron core. At this point, the iron core ceases to be an electromagnet. The hammer is pulled back to its original position due to the spring action of the steel rod and then touches the contact again to complete the circuit. The circuit is completed and current flows through the coil again, and the hammer strikes the bell again. The process repeats itself and you hear a ringing sound since the hammer keeps hitting the bell until the switch is released.

Details

An electric bell is a mechanical or electronic bell that functions by means of an electromagnet. When an electric current is applied, it produces a repetitive buzzing, clanging or ringing sound. Electromechanical bells have been widely used at railroad crossings, in telephones, fire and burglar alarms, as school bells, doorbells, and alarms in industrial areas, since the late 1800s, but they are now being widely replaced with electronic sounders. An electric bell consists of one or more electromagnets, made of a coil of insulated wire around an iron bar, which attract an iron strip armature with a clapper.

Types:

Interrupter bells

How they work

The most widely used form is the interrupter bell, which is a mechanical bell that produces a continuous sound when current is applied. See animation, above. The bell or gong (B), which is often in the shape of a cup or half-sphere, is struck by a spring-loaded arm (A) with a metal ball on the end called a clapper, actuated by an electromagnet (E). In its rest position the clapper is held away from the bell a short distance by its springy arm. When the switch (K) is closed, an electric current passes from the battery (U) through the winding of the electromagnet. It creates a magnetic field that attracts the iron arm of the clapper, pulling it over to give the bell a tap. This opens a pair of electrical contacts (T) attached to the clapper arm, interrupting the current to the electromagnet. The magnetic field of the electromagnet collapses, and the clapper springs away from the bell. This closes the contacts again, allowing the current to flow to the electromagnet again, so the magnet pulls the clapper over to strike the bell again. This cycle repeats rapidly, many times per second, resulting in a continuous ringing.

The tone of the sound generated depends on the shape and size of the bell or gong resonator. Where several bells are installed together, they may be given distinctive rings by using different size or shapes of gong, even though the strike mechanisms are identical.

Another type, the single-stroke bell, has no interrupting contacts. The hammer strikes the gong once each time the circuit is closed. These are used to signal brief notifications, such as a shop door opening for a customer, rather than continuous warnings.

Buzzers

An electric buzzer uses a similar mechanism to an interrupter bell, but without the resonant bell. They are quieter than bells, but adequate for a warning tone over a small distance, such as across a desktop.

A buzzer or beeper is an audio signalling device, which may be mechanical, electromechanical, or piezoelectric. Typical uses of buzzers and beepers include alarm devices, timers and confirmation of user input such as a mouse click or keystroke.

With the development of low cost electronics from the 1970s onwards, most buzzers have now been replaced by electronic 'sounders'. These replace the electromechanical striker of a bell with an electronic oscillator and a loudspeaker, often a piezoelectric transducer.

Single-stroke bells

The first commercial electric bells were used for railway signalling, between signal boxes. Complex bell codes were used to indicate the types of train passing between signal boxes, and the destinations to which they should be routed.

These were single-stroke bells: applying current to an electromagnet pulled the bell's clapper against the bell or gong and gave one chime. The bell did not ring continuously, but only with a single ring, until current was applied again. To sustain the tone, these bells were usually much larger than are used today with interrupter bells. Bells, gongs and spiral chimes could all be used, giving a distinct tone for each instrument.

A simple development of the single-stroke bell was the sprung bell. This had previously been used, mechanically actuated, for servant-call bells in large houses. Instead of working a clapper, the electromagnet shook the whole bell, which was mounted on a flexible spiral spring. The inertia of the heavy bell on the light spring would continue ringing for some seconds after the stroke. Although the sound would rapidly die away, the visible trembling of the bell could indicate which bell had been rung, amongst a panel of several.

Telephones

Landline telephone bells were powered by 60 to 500 volts RMS at between 16 and 25 Hertz AC. and a different design, the polarised bell, was used. These have an armature containing a permanent magnet, so that this is alternately attracted and repelled by each half-phase and different polarity of the supply. In practice, the armature is arranged symmetrically with two poles of opposite polarity facing each end of the coil, so that each may be attracted in turn. No contact breaker is required, so such bells are reliable for long service. In some countries, notably the UK, the clapper struck two different sized bells in turn giving a very distinctive ring.

Fire alarms

Fire alarm bells are divided into two categories: vibrating, and single-stroke. On a vibrating bell, the bell will ring continuously until the power is cut off. When power is supplied to a single-stroke bell, the bell will ring once and then stop. It will not ring again until power is turned off and on again. These were frequently used with coded pull stations.

Power sources

Electric bells are typically designed to operate on low voltages of from 5 to 24 V AC or DC. Before widespread distribution of electric power, bells were necessarily powered by batteries, either wet-cell or dry-cell type. Bells used in early telephone systems derived current by a magneto generator cranked by the subscriber. In residential applications, a small bell-ringing transformer is usually used to power the doorbell circuit. So that bell circuits can be made with low-cost wiring methods, bell signal circuits are limited in voltage and power rating. Bells for industrial purposes may operate on other, higher, AC or DC voltages to match plant voltages or available standby battery systems.

History

The interrupter bell evolved from various oscillating electromechanical mechanisms which were devised following the invention of the electromagnet by William Sturgeon in 1823. One of the first was the oscillating electric wire invented by James Marsh in 1824. This consisted of a wire pendulum dipping into a mercury trough, suspended between the poles of an electromagnet. When current was passed through the wire, the force of the magnet made the wire swing sideways, out of the mercury, which broke the current to the magnet, so the wire fell back. The modern electric bell mechanism had its origin in vibrating "contact breaker" or interrupter mechanisms devised to break the primary current in induction coils. Vibrating "hammer" interrupters were invented by Johann Philipp Wagner (1839) and Christian Ernst Neeff (1847), and was developed into a buzzer by Froment (1847). John Mirand around 1850 added a clapper and gong to make the standard electric bell for use as a telegraph sounder. Other types were invented around that time by Siemens and Halske and by Lippens. The polarized (permanent magnet) bell used in telephones, which appeared about 1860, had its beginning in the polarized relay and telegraph developed by Werner Siemens around 1850.

Additional Information:

Electric bell

An electric bell is an electromechanical device that works with the help of an electromagnet. When an electric current is applied to a traditional bell, the to and fro movement of a small hammer on a gong produces the sound of a bell. As a result, an electric bell is a device that is used to signal the presence of a guest or visitor.

When the electric bells are rung these days, they can even play songs or tunes. These mechanical-electric bells have been widely used in schools, burglar alarms, railway crossings, telephones, and industries since the 19th century. The electric bell, a first-of-its-kind invention, is widely used as an electronic sounder around the world. An electric bell is made up of an electromagnet attached to a strip of iron that causes the hammer to strike the gong, causing it to ring.

Working principle of electric bell

The principle of electromagnetism, or the magnetic effect of current, governs the operation of an electric bell. Magnetic fields are associated with moving electric charges, according to the electromagnetism phenomenon. A magnetic field is created whenever an electric current flows through a conductor. The right-hand-thumb rule can be used to determine the direction of this magnetic field. This principle is used to make electromagnets. Electromagnets can be found in a variety of electronic devices, including televisions, radios, speakers, and even an electric bell.

Electromagnets

An electromagnet is a man-made magnet that generates a magnetic field when current flows through it. A wire wound in a coil makes up an electromagnet. When an electric current flows through a wire, it creates a magnetic field around it, making the wire act like an electromagnet. The magnetic field created by an electromagnet lasts as long as current flows through it. Increase the number of turns in the coil, increase the current through the coil, and wind the coil around a magnetic material like soft iron to strengthen the magnetic field of an electromagnet. As long as there is electric power across its ends, an electromagnet behaves similarly to a regular magnet. The magnetic field around the electromagnet vanishes when the electric power is turned off.

It appears to me that if one wants to make progress in mathematics, one should study the masters and not the pupils. - Niels Henrik Abel.

Nothing is better than reading and gaining more and more knowledge - Stephen William Hawking.

Offline

#2655 2025-12-06 17:03:02

- Jai Ganesh

- Administrator

- Registered: 2005-06-28

- Posts: 53,507

Re: Miscellany

2455) Marsupials

Gist

Marsupials are the group of mammals commonly thought of as pouched mammals (like the wallaby and kangaroo at left). They give live birth, but they do not have long gestation times like placental mammals.

A marsupial is a mammal known for giving birth to underdeveloped young that continue to develop in a pouch (marsupium) on the mother's belly, feeding from teats inside. Key examples include kangaroos, koalas, opossums, and wombats, primarily found in Australia, though opossums are the only native U.S. species. Their young, called joeys, are born tiny and crawl into the pouch to nurse and grow, and they often have unique features like strong hind legs for hopping or specialized teeth.

Summary

Marsupials are a diverse group of mammals belonging to the infraclass Marsupialia. They are natively found in Australasia, Wallacea, and the Americas. One of marsupials' unique features is their reproductive strategy: the young are born in a relatively undeveloped state and then nurtured within a pouch on their mother's abdomen.

Extant marsupials encompass many species, including kangaroos, koalas, opossums, possums, Tasmanian devils, wombats, wallabies, and bandicoots.

Marsupials constitute a clade stemming from the last common ancestor of extant Metatheria, which encompasses all mammals more closely related to marsupials than to placentals. The evolutionary split between placentals and marsupials occurred 125–160 million years ago in the Middle Jurassic–Early Cretaceous period.

Presently, close to 70% of the 334 extant marsupial species are concentrated on the Australian continent, including mainland Australia, Tasmania, New Guinea, and nearby islands. The remaining 30% are distributed across the Americas, primarily in South America, with thirteen species in Central America and a single species, the Virginia opossum, inhabiting North America north of Mexico.

Marsupial sizes range from a few grams in the long-tailed planigale, to several tons in the extinct Diprotodon.

The word marsupial comes from marsupium, the technical term for the abdominal pouch. It, in turn, is borrowed from the Latin marsupium and ultimately from the ancient Greek mársippos, meaning "pouch".

Details

A marsupial is any of more than 250 species belonging to the infraclass Metatheria (sometimes called Marsupialia), a mammalian group characterized by premature birth and continued development of the newborn while attached to the nipples on the mother’s lower belly. The pouch—or marsupium, from which the group takes its name—is a flap of skin covering the nipples. Although prominent in many species, it is not a universal feature. In some species the nipples are fully exposed or are bounded by mere remnants of a pouch. The young remain firmly attached to the milk-giving teats for a period corresponding roughly to the latter part of development of the fetus in the womb of a placental mammal (eutherian).

The largest and most-varied assortment of marsupials—some 200 species—is found in Australia, New Guinea, and neighbouring islands, where they make up most of the native mammals found there. In addition to larger species such as kangaroos, wallabies, wombats, and the koala (Phascolarctos cinereus), there are numerous smaller forms, many of which are carnivorous, with the Tasmanian devil (Sarcophilus harrisii) being the largest of this group (family Dasyuridae). About 70 species live in the Americas, mainly in South and Central America, but one, the Virginia opossum (Didelphis virginiana), ranges through the United States into Canada. The largest living marsupial is the red kangaroo (Macropus rufus), males of which can grow to about 2 metres (6.6 feet) in height, 3 metres (10 feet) from muzzle to tail tip, and a weight of up to 90 kg (about 200 pounds). The smallest are the planigales (see marsupial mouse), especially the long-tailed planigale (Planigale ingrami), measuring barely 12 cm (4.7 inches) in total length. Most marsupials range from the size of a squirrel to that of a medium-size dog.

The structural and behavioral parallels with placental mammals are sometimes quite striking. Such resemblances are examples of convergent evolution—a tendency for organisms to adapt in similar ways to similar habitats. Thus, there are marsupials that look remarkably like moles, shrews, squirrels, mice, dogs, and hyenas. Others are the ecological counterparts, less in structure than in habits, of cats, small bears, and rabbits. Even the larger grazing marsupials (such as kangaroos), which resemble no placental mammals, can be thought of as filling the same ecological role (niche) as the deer and antelope found elsewhere.

The niches that marsupials fill are closely associated with structure. The burrowing species, such as the marsupial moles (Notoryctes typhlops and N. caurinus) and the wombats, have powerful foreclaws with which they can tunnel into the ground for food and shelter. Terrestrial forms, such as kangaroos and wallabies, possess well-developed hind limbs that serve both as formidable weapons and as catapults by which they can bound over the plains. The gliders have a membrane along either flank, attached to the forelegs and hind legs, that enables these arboreal animals to glide down from a high perch. A few marsupials—such as tree kangaroos, koalas, and some cuscuses—spend most of their lives in trees. The water opossum, or yapok (Chironectes minimus), of Central and South America is semiaquatic.

The diets of marsupials are as varied as the niches they occupy. Many dasyurids live chiefly on insects and other small animals. Dunnarts (Sminthopsis) are so hyperactive—like shrews—that, in order to supply their high energy needs, they must devour their own weight in food (chiefly insects) each day. The numbat uses its remarkable wormlike tongue to lap up termites and ants. Many Australian possums, bandicoots, and American opossums have a mixed diet of plants and insects. Wombats and many other marsupials are strictly vegetarian. The small honey possum (Tarsipes rostratus) is specialized to feed on the nectar of flowers, and other marsupials also may serve as important pollinators in that way. Few large carnivores have ever evolved in Australia, because of the low productivity of its environment. The most-recent large carnivorous marsupials to evolve—the Tasmanian devil and the now-extinct thylacine, or Tasmanian wolf (Thylacinus cynocephalus)—were both displaced on the mainland by the dingo.

Marsupials are notably less intelligent than placental mammals, partly because of their simpler brains. Compared with that of placentals, the brain of marsupials differs markedly in both structure and bulk. Most notably, it lacks a corpus callosum, the part of the placental brain that connects the two cerebral halves. The marsupial brain is also smaller relative to overall body size; for example, a quoll has about half as much brain tissue as a placental cat of similar skull size. It is not surprising, therefore, to find that marsupial behaviour differs somewhat from that of placentals. One peculiarity that may stem from that underdevelopment is restricted vocal ability. Although marsupials are not entirely silent, few emit loud sounds of excitement or distress; apparently, none utters grunts of contentment or even cries of hunger when young. Their vocalizing is more limited and less variable than that of placentals. The ferocious-sounding rutting roars of male koalas are a dramatic and unexpected exception.

There seems to be little permanent social organization among most marsupials beyond short-lived pair bonds during mating. Many of the grazing marsupials, such as kangaroos and wallabies, move in feeding groups called mobs, but those associations are not true social groups, as there is no attention paid to any leaders or elders. Only the lesser gliders (Petaurus) have permanent cohesive social groupings.

The life cycle of marsupials exhibits peculiarities that have long been considered primitive compared with those of placental mammals but are more likely adaptations to low-productivity environments. The uterine cycle of the female marsupial has no secretory phase, and the uterine wall is not specialized for embryo implantation, although a transitory placenta does exist in the bandicoots. The period of intrauterine development in marsupials ranges from about 12 days in the bilby (Macrotis lagotis) to 38 days in the swamp wallaby (Wallabia bicolor).

The young, born in a vulnerable embryonic condition, make their own way to the shelter, warmth, and nourishment of the pouch; in pouchless marsupials the young simply cling to the teats. Those fortunate enough to survive that arduous journey may succeed in attaching themselves to the mother’s nipples, which then swell and become firmly fastened—almost physically fused—to the mouth tissues of the young. In that condition the young continue their development for weeks or months, after which they are weaned and begin to look after themselves. Frequently, the partially developed young outnumber the available teats, and the excess individuals perish.

Additional Information

There are over 330 species of marsupials. Around two-thirds of them live in Australia. The other third live mostly in South America

A marsupial is born in a very incomplete state. They are minute, blond, hairless and with hindlimbs only partially formed. The forelimbs however are developed, and the toes are armed with sharp, curved claws. They use these claws to make the journey to the pouch, many times the body length of the one month old foetus.

Marsupials have a short-lived placenta that nourishes their young for just a few days before they’re born, the rest of their nutrition coming from the mother’s teats inside the pouch. Instead of the placenta, the mother’s milk nourishes the young and allows it to grow and develop.

Although the word ‘marsupial’ comes from the Latin word ‘marsupium’, which means pouch, not all marsupials have pouches. The pouch is designed to protect the offspring while they suckle on the nipples, however some in some species this is just a fold, not something the young can fit inside for their joey stage of development.

Marsupials have an extra pubic bone, the epipubic bone, to support their pouch.

The toes of many marsupials appear conjoined with webbing, a mutation known as syndactyly. The koala is a perfect example.

Australian marsupials can be categorised by what they eat into 3 groups:

Dasyurids - these are the meat-eating marsupials: quolls, the tamanian devil, tasmanian tiger, numbats, dunnarts, antechinus.

Peramelemorphs - these are the omnivorous marsupials: bilbies and bandicoots.

Diprotodonts - these are the largely herbivorous marsupials: kangaroos, wallabies, possums, koalas, wombats.

It appears to me that if one wants to make progress in mathematics, one should study the masters and not the pupils. - Niels Henrik Abel.

Nothing is better than reading and gaining more and more knowledge - Stephen William Hawking.

Offline

#2656 2025-12-07 17:55:14

- Jai Ganesh

- Administrator

- Registered: 2005-06-28

- Posts: 53,507

Re: Miscellany

2456) Electric Eel

Gist

Electric eels produce electricity using thousands of stacked, disc-like cells called electrocytes, modified muscle cells that act like tiny batteries, creating a voltage difference. When triggered by the nervous system, these cells discharge simultaneously, sending a strong electrical pulse through the water for stunning prey or defense, similar to a biological battery pack.

They are known for their ability to stun their prey by generating electricity, delivering shocks at up to 860 volts. Their electrical capabilities were first studied in 1775, contributing to the invention of the electric battery in 1800.

Summary

The electric eel gets its name from its shocking abilities! Special organs in the eel’s body release powerful electric charges of up to 650 volts—that’s more than five times the power of a standard United States wall socket!

Physical Description

The electric eel has a slender, snake-like body and flattened head. Its thick, scaleless skin is generally dark gray to brown, and its underside is a yellow-orange color.

Similar to other eel shaped fish, the electric eel lacks pelvic fins. It has a small, or reduced, caudal fin and also lacks dorsal fins. Instead, an elongated anal fin helps it maneuver through the water, where it can swim forward, backward or hover, as it searches for prey.

Three specialized electric organs—the main electrical organ, the Hunter’s organ and the Sachs’ organ—make up about 80 percent of this fish’s body. Its remaining vital organs are tightly packed within the anterior, or front, part of its body.

The electric organs create strong and weak electric charges, which are utilized for defense, hunting, communication and navigation. Stronger electric charges can be energetically exhausting for this fish. Its strongest electric pulses are produced by the main electrical organ, as well as two-thirds of the Hunter’s organ. The remainder of the Hunter’s organ and the Sachs’ organ produce the weaker electric discharges.

Size

Electric eels grow to lengths of 6 to 8 feet (2 to 2.5 meters).

Native Habitat

This species is widely distributed across northern South America. Its range spans across Brazil, the Guianas, Suriname, Venezuela, Colombia, Ecuador and Peru. Electric eels inhabit the quiet, slow-moving waters of ox-bow lakes, streams, pools and flooded forests of the Amazon and Orinoco Rivers, preferring side channels but also living further inland.

Both of the rivers these fish inhabit are subject to a natural fluctuation of water driven by precipitation patterns, which results in two distinct seasons: wet and dry. The two seasons bring about drastic changes in available habitat for electric eels.

During the rainy season, the rivers swell, re-connecting lakes and ponds as the forests flood. Juvenile electric eels disperse and expand into new territories. As water recedes in the dry season, large groups of fish become isolated in the pools and smaller streams that remain.

The water in these areas is poorly oxygenated, but electric eels are specially adapted to thrive in this environment. They are obligate air-breathers, which means they surface for air periodically. Their mouths are heavily vascularized with folds that increase the surface area, allowing them to breathe air, rather than trying to meet their respiration needs through gills in warm, anoxic waters.

Throughout the dry season, the electric eel is also at greater risk from predators, such as large mammals, that hunt from outside the shallow waters it inhabits. Because there is little space to retreat, the fish is often forced to defend itself.

Water efficiently conducts electricity, providing a wide surface area for the electric eel’s shock to be applied. This means that an electric pulse delivered through the water may not be as painful for a large predator as one delivered outside of the water. As such, an electric eel can instead jump out of the water, sliding its body up against a partially submerged predator to directly target its shock. The eel then delivers its electric pulses in increasing voltages.

Lifespan

The average lifespan of electric eels in the wild is still unknown. In human care, males typically live 10 to 15 years, and females generally live 12 to 22 years.

Communication

Electric eels communicate using low electric organ discharges. This electricity is produced in pulses, and the duration of a pulse is much shorter than the time that lapses between each pulse. The frequency at which weaker electric pulses are produced varies between males and females, as well as across individuals.

Electric eels can detect these signals and interpret information about other individuals in the water. They can even convey information about their sex and sexual receptivity, which is important during the breeding season.

Electric eels are not the only fish to communicate using electric organ discharges. More than 220 species of South American knifefish in the electric eel's lineage use this highly advanced method of communication and detection.

Food/Eating Habits

Adult electric eels are generalist carnivores, eating fish, crustaceans, insects and small vertebrates, such as amphibians, reptiles and mammals. Juveniles feed primarily on invertebrates, and newly hatched electric eels will eat remaining, unhatched eggs.

In addition to defense, electric eels use their shocking power to hunt. In the dark and murky waters they inhabit, prey can be difficult to spot. To aid its hunt, the electric eel has motion-sensitive hairs along its body (the lateral line system) that detect any slight pressure change in the surrounding water. When the eel suspects a prey item is nearby, it emits two rapid electric pulses, called a doublet.

This doublet affects the muscles of the prey, causing it to twitch involuntarily and alerting the electric eel to its presence. With a series of high-voltage pulses (as many as 400 per second), it then paralyzes and consumes its prey. This entire process happens so quickly that it can be difficult for the human eye to observe in detail.

Reproduction and Development

Female electric eels lay between 1,200 and 1,700 eggs during the dry season. Males construct nests made of saliva and guard the larvae until the rainy season begins. This parental care may be the result of increased food competition and potential for predation during the dry season.

More research on the reproductive cycle and behavior of electric eels is needed to determine exactly how spawning takes place. Some researchers posit that spawning occurs in successive batches throughout the dry season, while other accounts document that all eggs are deposited at once.

Details

The electric eels are a genus, Electrophorus, of neotropical freshwater fish from South America in the family Gymnotidae, of which they are the only members of the subfamily Electrophorinae. They are known for their ability to stun their prey by generating electricity, delivering shocks at up to 860 volts. Their electrical capabilities were first studied in 1775, contributing to the invention of the electric battery in 1800.

Despite their name, electric eels are not closely related to the true eels (Anguilliformes) but are members of the electroreceptive knifefish order Gymnotiformes. This order is more closely related to catfish. In 2019, electric eels were split into three species: for more than two centuries before that, the genus was believed to be monotypic, containing only Electrophorus electricus.

They are nocturnal, obligate air-breathing animals, with poor vision complemented by electrolocation; they mainly eat fish. Electric eels grow for as long as they live, adding more vertebrae to their spinal column. Males are larger than females. Some captive specimens have lived for over 20 years.

Evolution:

Taxonomy

When electric eels were described by Carl Linnaeus in 1766, based on early field research by Europeans in South America and specimens sent back to Europe for study, he used the name Gymnotus electricus, placing it in the same genus as Gymnotus carapo (the banded knifefish). He noted that the fish is from the rivers of Surinam, that it causes painful shocks, and that it had small pits around the head.

In 1864, Theodore Gill moved the electric eel to its own genus, Electrophorus. The name is from the Greek (ḗlektron 'amber, a substance able to hold static electricity'), and (phérō 'I carry'), giving the meaning 'electricity bearer'. In 1872, Gill decided that the electric eel was sufficiently distinct to have its own family, Electrophoridae. In 1998, Albert and Campos-da-Paz lumped the Electrophorus genus with the family Gymnotidae, alongside Gymnotus, as did Ferraris and colleagues in 2017.

In 2019, C. David de Santana and colleagues divided E. electricus into three species based on DNA divergence, ecology and habitat, anatomy and physiology, and electrical ability. The three species are E. electricus (now in a narrower sense than before), and the two new species E. voltai and E. varii. However, this revision did not address Electrophorus multivalvulus, which was described from the Peruvian Amazon by Nakashima in 1941. Therefore, E. varii (described from the same region) may be a junior synonym of E. multivalvulus and has been regarded as such by some biologists.

Phylogeny

Electric eels form a clade of strongly electric fishes within the order Gymnotiformes, the South American knifefishes. Electric eels are thus not closely related to the true eels (Anguilliformes). The lineage of the Electrophorus genus is estimated to have split from its sister taxon Gymnotus sometime in the Cretaceous. Most knifefishes are weakly electric, capable of active electrolocation but not of delivering shocks. Their relationships, as shown in the cladogram, were analysed by sequencing their mitochondrial DNA in 2019. Actively electrolocating fish are marked with a small yellow lightning flash symbol for electrolocating fish. Fish able to deliver electric shocks are marked with a red lightning flash.

Additional Information

Electric eel, (genus Electrophorus), is any of three species of elongated South American knifefishes that produce powerful electric shocks to stun prey, usually other fish. All three species—the electric eel (Electrophorus electricus), Vari’s electric eel (E. varii), and Volta’s electric eel (E. voltai)—are found in the Amazon River or its tributaries.

Prey capture and electrical discharge

Electric eels have three electric organs—the main organ, Hunter’s organ, and Sach’s organ—which are made up of modified muscle cells. The main electric organ is located on the dorsal side; it spans the middle half of the body from just behind the head to the middle of the tail. Hunter’s organ parallels the main organ but on the ventral side. Those organs generate the high-voltage pulses that stun prey and deter predators. The rear quarter of the electric eel contains Sach’s organ, which produces lower-voltage pulses that allow the electric eel to communicate and navigate murky waters. Sach’s organ also contains the electric eel’s negative pole.

An electric eel can deliver a shock because its nervous system contains a number of disc-shaped electrogenic (electricity-producing) cells called electrocytes. Each electrocyte carries a net negative electric charge; the electrocyte’s inner periphery is negatively charged and has a potential difference of just under 100 millivolts relative to the deeper parts of the cell’s interior (which has a high concentration of positively charged potassium ions). When the shock command is delivered to these cells by the neurotransmitter acetylcholine, a path of low electrical resistance develops between one side of the cell and the interior. Through active transport (see cell: transport across the membrane), potassium ions outside the cell rush inward on that side, which causes some of the potassium ions inside the cell to exit the other side to maintain the cell’s equilibrium. With this process about 50 millivolts of electricity is released from the cell. Since the electrogenic cells are stacked next to one another, the activity of one cell firing sets off others around it, creating a cascade of current. The collective discharge of electricity from each electrocyte in the chain allows the electric eel to release up to 860 volts. Studies have shown that shocks from juvenile electric eels making leaping attacks can discharge more than 120 volts, which, after other factors are considered, can impart 40–50 milliamps of current on its victim, an amount large enough to cause intense pain in humans.

The electric eel’s penchant for shocking its prey may have evolved to protect its sensitive mouth from injury from often spiny struggling fish. The shocked prey is stunned long enough to be sucked through the mouth directly to the stomach. Sometimes the electric eel does not bother to stun prey but simply gulps faster than the prey can react. The electrical discharges also may be used to keep prey from escaping or to induce a twitching response in hidden prey that causes the prey to reveal its position. Such prey-capture tactics are commonly employed by single eels; however, at least one species also engages in social predation (pack hunting). Volta’s electric eels (E. voltai) coordinate their movements and the timing and strength of their electrical discharges to ambush or corral schools of fish before stunning and capturing individual prey.

Electric eels have been shown to curl their bodies around larger or more elusive prey. That strategy has the effect of doubling the strength of the electric field between the electric eel’s positive pole (which is located near the head) and its negative pole (which is located near the tail). The electric eel then delivers a series of shocks that occur at one-millisecond intervals. Each shock forces involuntary muscle contractions that fatigue the prey’s muscles, which allows the electric eel to better manipulate it for consumption.

Electric eels may also use their ability to shock other animals to defend themselves against predators and perceived threats. While an electric eel is fully submerged, its electrical discharge is weaker because the shock is distributed throughout the surrounding water. Stronger shocks, however, may be delivered by leaping out of the water or by extending the head up and out of the water to place the chin against a partially submerged animal. The strength of the electric current delivered in this fashion is not dampened by the watery medium. The electric current enters the animal’s body directly before traveling through the submerged parts of its body and back into the water to the tail of the electric eel, thereby completing the electric circuit.

Physical features

Long, cylindrical, scaleless, and usually gray-brown (sometimes with a red underside), electric eels can grow to 2.75 metres (9 feet) and weigh 22 kg (48.5 pounds). The tail region constitutes about four-fifths of an electric eel’s total length, which is bordered along the underside by an undulating anal fin that is used to propel the fish. Despite its name, it is not a true eel but is related to the characin fishes, which include piranhas and neon tetras.

Electric eels are sluggish creatures that prefer slow-moving fresh water, where they surface every few minutes to gulp air. Their mouth is rich with blood vessels that allow use of the mouth as a lung. The vestigial gills are used only to eliminate carbon dioxide, not for oxygen uptake.

Electric eels are among the principal aquatic predators of the white-water flooded forest known as varzea. In one fish survey of a typical varzea, electric eels made up more than 70 percent of the fish biomass. Electric eels also eat fruit that falls from trees whose canopies hang over rivers. Consequently, they aid in seed dispersal via defecation.

It appears to me that if one wants to make progress in mathematics, one should study the masters and not the pupils. - Niels Henrik Abel.

Nothing is better than reading and gaining more and more knowledge - Stephen William Hawking.

Offline

#2657 2025-12-08 16:22:02

- Jai Ganesh

- Administrator

- Registered: 2005-06-28

- Posts: 53,507

Re: Miscellany

2457) Snow Leopard

Gist

The snow leopard is also known as the ounce, from an old French word, and locally by names like "Shan" (Ladakhi) or "Bars" (Kazakh), but its most famous nickname is the "ghost of the mountains" due to its elusive nature. Its scientific name, Panthera uncia, reflects its connection to big cats, though it was once classified separately as Uncia uncia.

The snow leopard (Panthera uncia) is a species of large cat in the genus Panthera of the family Felidae.

Summary

The snow leopard (Panthera uncia) is a species of large cat in the genus Panthera of the family Felidae. The species is native to the mountain ranges of Central and South Asia. It is listed as Vulnerable on the IUCN Red List because the global population is estimated to number fewer than 10,000 mature individuals and is expected to decline about 10% by 2040. It is mainly threatened by poaching and habitat destruction following infrastructural developments. It inhabits alpine and subalpine zones at elevations of 3,000–4,500 m (9,800–14,800 ft), ranging from eastern Afghanistan, the Himalayas and the Tibetan Plateau to southern Siberia, Mongolia and western China. In the northern part of its range, it also lives at lower elevations.

Taxonomically, the snow leopard was long classified in the monotypic genus Uncia. Since phylogenetic studies revealed the relationships among Panthera species, it has since been considered a member of that genus. Two subspecies were described based on morphological differences, but genetic differences between the two have not yet been confirmed. It is therefore regarded as a monotypic species. The species is widely depicted in Kyrgyz culture.

(IUCN: International Union for Conservation of Nature ).

Details

Snow leopards have evolved to live in some of the harshest conditions on Earth. Their thick white-gray coat, spotted with large black rosettes, blends in perfectly with Asia’s steep and rocky, high mountains. Because of their incredible natural camouflage, rendering them almost invisible in their surroundings, snow leopards are often referred to as the “ghost of the mountains.”

The snow leopard’s powerful build allows it to scale great, steep slopes with ease. Its hind legs give the snow leopard the ability to leap six times the length of its body. A long tail enables agility, provides balance, and wraps around the resting snow leopard as protection from the cold.

For millennia, this magnificent cat was the king of the mountains. The mountains were rich with their prey, such as blue sheep, Argali wild sheep, ibex, marmots, pikas and hares. The snow leopard’s habitat range extends across the mountainous regions of 12 countries across Asia: Afghanistan, Bhutan, China, India, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyz Republic, Mongolia, Nepal, Pakistan, Russia, Tajikistan, and Uzbekistan. The total range covers an area of close to 772,204 square miles, with 60% of the habitat found in China. However, more than 70% of snow leopard habitat remains unexplored. Home range sizes can vary from 4.6-15.4 square miles in Nepal to over 193 square miles in Mongolia. And population density can range from <0.1 to 10 or more individuals per 38.6 square miles, depending on prey densities and habitat quality. Nevertheless, the snow leopard population is very likely declining.

Additional Information

A snow leopard is a large long-haired Asian cat, classified as either Panthera uncia or Uncia uncia in the family Felidae. The snow leopard inhabits the mountains of central Asia and the Indian subcontinent, ranging from an elevation of about 1,800 metres (about 6,000 feet) in the winter to about 5,500 metres (18,000 feet) in the summer.

Its soft coat, consisting of a dense insulating undercoat and a thick outercoat of hairs about 5 cm (2 inches) long, is pale grayish with dark rosettes and a dark streak along the spine. The underparts, on which the fur may be 10 cm (4 inches) long, are uniformly whitish. The snow leopard attains a length of about 2.1 metres (7 feet), including the 0.9-metre- (3-foot-) long tail. It stands about 0.6 metre (2 feet) high at the shoulder and weighs 23–41 kg (50–90 pounds). It hunts at night and preys on various animals, such as marmots, wild sheep, ibex (Capra), and domestic livestock. Its litters of two to four young are born after a gestation period of approximately 93 days.

Formerly classified as Leo uncia, the snow leopard has been placed—with the lion, tiger, and other big cats—in the genus Panthera. Because of the presence of certain skeletal features, such as having a shorter skull and having more-rounded eye orbits than other big cats, the snow leopard has also been classified by some authorities as the sole member of the genus Uncia. Genetic studies show that the common ancestor of snow leopards and tigers diverged from the lineage of big cats about 3.9 million years ago and that snow leopards branched from tigers about 3.2 million years ago.

Between 1986 and 2017 the snow leopard was listed as an endangered species on the Red List of Threatened Species from the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN). However, in 2017 the species’ status was changed to “vulnerable” after a population calculation error was discovered in the species’ 2008 population assessment. Between 2,500 to 10,000 adult snow leopards remain in the wild, but the species continues to face daunting threats to its survival.

Several factors have contributed to their decline. Their wild prey has decreased as herding and ranching activities have expanded throughout their geographic range. They are often killed by herders and ranchers whose livestock they have taken, and their bones and hides are sought after by hunters and poachers for the illegal animal trade.

It appears to me that if one wants to make progress in mathematics, one should study the masters and not the pupils. - Niels Henrik Abel.

Nothing is better than reading and gaining more and more knowledge - Stephen William Hawking.

Offline

#2658 2025-12-09 17:20:40

- Jai Ganesh

- Administrator

- Registered: 2005-06-28

- Posts: 53,507

Re: Miscellany

2458) RADAR

Gist

RADAR stands for Radio Detection And Ranging, a system that uses radio waves to detect, locate, and track objects by sending out signals and analyzing the returning echoes to determine distance, speed, and direction, effective even in poor visibility for things like aircraft, ships, weather, and vehicles. It's crucial in aviation, shipping, meteorology, and traffic control.

The principle of Radar (Radio Detection And Ranging) is to detect objects by sending out electromagnetic waves (radio waves) and analyzing the returning echoes, much like SONAR uses sound. A transmitter sends pulses, an antenna radiates them, and the signal reflects off targets, returning as weak echoes. By measuring the time delay and direction of these returning signals, the radar system calculates an object's distance, bearing (direction), and velocity (using Doppler shift), displaying the information visually.

Summary