Math Is Fun Forum

You are not logged in.

- Topics: Active | Unanswered

#1851 2026-01-19 21:46:13

- Jai Ganesh

- Administrator

- Registered: 2005-06-28

- Posts: 52,897

Re: crème de la crème

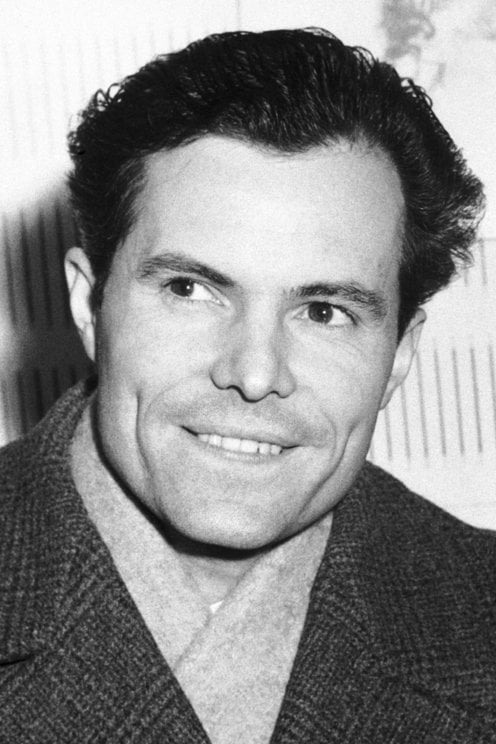

2414) Rudolf Mössbauer

Gist:

Work

According to the principles of quantum physics, the atomic nucleus and surrounding electrons can have only fixed energy levels. When there are transitions among energy levels in the atomic nucleus, high-energy photons known as gamma rays are emitted and absorbed. In a gas a recoil effect occurs when an atom emits a photon. In 1958 Rudolf Mössbauer discovered that the recoil can be eliminated if the atoms are embedded in a crystal structure. This opened up opportunities to study energy levels in atomic nuclei and how these are affected by their surroundings and various phenomena.

Summary

Rudolf Ludwig Mössbauer (born January 31, 1929, Munich, Germany—died September 14, 2011, Grünwald) was a German physicist and winner, with Robert Hofstadter of the United States, of the Nobel Prize for Physics in 1961 for his discovery of the Mössbauer effect.

Mössbauer discovered the effect in 1957, one year before he received his doctorate from the Technical University in Munich. Under normal conditions, atomic nuclei recoil when they emit gamma rays, and the wavelength of the emission varies with the amount of recoil. Mössbauer found that at a low temperature a nucleus can be embedded in a crystal lattice that absorbs its recoil. The discovery of the Mössbauer effect made it possible to produce gamma rays at specific wavelengths, and this proved a useful tool because of the highly precise measurements it allowed. The sharply defined gamma rays of the Mössbauer effect have been used to verify Albert Einstein’s general theory of relativity and to measure the magnetic fields of atomic nuclei.

Mössbauer became professor of physics at the California Institute of Technology, Pasadena, in 1961. Three years later he returned to Munich to become professor of physics at the Technical University, where he retired as professor emeritus in 1997.

Details

Rudolf Ludwig Mössbauer (31 January 1929 – 14 September 2011) was a German physicist who shared the 1961 Nobel Prize in Physics with Robert Hofstadter for his discovery of the Mössbauer effect, which is the basis for Mössbauer spectroscopy.

Career

Mössbauer was born in Munich, where he also studied physics at the Technical University of Munich. He prepared his Diplom thesis in the Laboratory of Applied Physics of Heinz Maier-Leibnitz and graduated in 1955. He then went to the Max Planck Institute for Medical Research in Heidelberg. Since this institute, not part of a university, had no right to award a doctorate, Mössbauer remained under the auspices of Maier-Leibnitz, his official thesis advisor, when he passed his PhD exam in Munich in 1958.

In his PhD, he discovered the recoilless nuclear fluorescence of gamma rays in 191 iridium, the Mössbauer effect. His fame grew immensely in 1960 when Robert Pound and Glen Rebka used this effect to prove the red shift of gamma radiation in the gravitational field of the Earth; this Pound–Rebka experiment was one of the first experimental precision tests of Albert Einstein's general theory of relativity. However, the long-term importance of the Mössbauer effect is its use in Mössbauer spectroscopy. Along with Robert Hofstadter, Rudolf Mössbauer was awarded the 1961 Nobel Prize in Physics.

On the suggestion of Richard Feynman, Mössbauer was invited in 1960 to Caltech in the USA, where he advanced rapidly from research fellow to senior research fellow; he was appointed a full professor of physics in early 1962. In 1964, his alma mater, the Technical University of Munich (TUM), convinced him to go back as a full professor. He retained this position until he became professor emeritus in 1997. As a condition for his return, the faculty of physics introduced a "department" system. This system, strongly influenced by Mössbauer's American experience, was in radical contrast to the traditional, hierarchical "faculty" system of German universities, and it gave the TUM an eminent position in German physics.

In 1972, Rudolf Mössbauer went to Grenoble to succeed Heinz Maier-Leibnitz as the director of the Institut Laue-Langevin just when its newly built high-flux research reactor went into operation. After serving a five-year term, Mössbauer returned to Munich, where he found his institutional reforms reversed by overarching legislation. Until the end of his career, he often expressed bitterness over this "destruction of the department." Meanwhile, his research interests shifted to neutrino physics.

Mössbauer was regarded as an excellent teacher. He gave highly specialized lectures on numerous courses, including Neutrino Physics, Neutrino Oscillations, The Unification of the Electromagnetic and Weak Interactions and The Interaction of Photons and Neutrons With Matter. In 1984, he gave undergraduate lectures to 350 people taking the physics course. He told his students: “Explain it! The most important thing is that you can explain it! You will have exams, there you have to explain it. Eventually, you pass them, you get your diploma and you think, that's it! – No, the whole life is an exam, you'll have to write applications, you'll have to discuss with peers... So learn to explain it! You can train this by explaining to another student, a colleague. If they are not available, explain it to your mother – or to your cat!”

Personal life

Mössbauer married Elizabeth Pritz in 1957. They had a son, Peter and two daughters Regine and Susi. They divorced in 1983, and he married his second wife Christel Braun in 1985.

Mössbauer died at Grünwald, Germany on 14 September 2011 at 82.

It appears to me that if one wants to make progress in mathematics, one should study the masters and not the pupils. - Niels Henrik Abel.

Nothing is better than reading and gaining more and more knowledge - Stephen William Hawking.

Offline

#1852 Yesterday 16:56:02

- Jai Ganesh

- Administrator

- Registered: 2005-06-28

- Posts: 52,897

Re: crème de la crème

2415) Melvin Calvin

Gist:

Work

One of the most fundamental processes of life is photosynthesis. Green plants use energy from sunlight to make carbohydrates out of water and carbon dioxide in the air. Through studies during the early 1950s, particularly of single-cell green algae, Melvin Calvin and his colleagues traced the path taken by carbon through different stages of photosynthesis. For this they made use of tools such as radioactive isotopes and chromatography. Their findings included insight into the important role played by phosphorous compounds during the composition of carbohydrates.

Summary

Melvin Ellis Calvin (April 8, 1911 – January 8, 1997) was an American biochemist known for discovering the Calvin cycle along with Andrew Benson and James Bassham, for which he was awarded the 1961 Nobel Prize in Chemistry. He spent most of his five-decade career at the University of California, Berkeley.

Early life and education

Melvin Calvin was born in St. Paul, Minnesota, the son of Elias Calvin and Rose Herwitz, Jewish immigrants from the Russian Empire (now known as Lithuania and Georgia).

At an early age, Melvin Calvin’s family moved to Detroit, Michigan where his parents ran a grocery store to earn their living. Melvin Calvin was often found exploring his curiosity by looking through all of the products that made up their shelves.

After he graduated from Central High School in 1928, he went on to study at Michigan College of Mining and Technology (now known as Michigan Technological University) where he received the school’s first Bachelors of Science in Chemistry. He went on to earn his PhD at the University of Minnesota in 1935. While under the mentorship of George Glocker, he studied and wrote his thesis on the electron affinity of halogens. He was invited to join the lab of Michael Polanyi as a Post Doctoral student at the University of Manchester. The two years he spent at the lab were focused on studying the structure and behavior of organic molecules. In 1942, He married Marie Genevieve Jemtegaard, and they had three daughters, Elin, Sowie, and Karole, and a son, Noel.

Career

On a visit to the University of Manchester, Joel Hildebrand, the director of UC Radiation Laboratory, invited Calvin to join the faculty at the University of California, Berkeley. This made him the first non-Berkeley graduate hired by the chemistry department in +25 years. He invited Calvin to push forward in radioactive carbon research because "now was the time". Calvin's original research at UC Berkeley was based on the discoveries of Martin Kamen and Sam Ruben in long-lived radioactive carbon-14 in 1940.

In 1947, he was promoted to a Professor of Chemistry and the director of the Bio-Organic Chemistry group in the Lawrence Radiation Laboratory. The team he formed included: Andrew Benson, James A. Bassham, and several others. Andrew Benson was tasked with setting up the photosynthesis laboratory. The purpose of this lab was to discover the path of carbon fixation through the process of photosynthesis. The greatest impact of the research was discovering the way that light energy converts into chemical energy. Using the carbon-14 isotope as a tracer, Calvin, Andrew Benson and James Bassham mapped the complete route that carbon travels through a plant during photosynthesis, starting from its absorption as atmospheric carbon dioxide to its conversion into carbohydrates and other organic compounds. The process is part of the photosynthesis cycle. It was given the name the Calvin–Benson–Bassham Cycle, named for the work of Melvin Calvin, Andrew Benson, and James Bassham. There were many people who contributed to this discovery but ultimately Melvin Calvin led the charge.

In 1963, Calvin was given the additional title of Professor of Molecular Biology. He was founder and Director of the Laboratory of Chemical Biodynamics, known as the “Roundhouse”, and simultaneously Associate Director of Berkeley Radiation Laboratory, where he conducted much of his research until his retirement in 1980. In his final years of active research, he studied the use of oil-producing plants as renewable sources of energy. He also spent many years testing the chemical evolution of life and wrote a book on the subject that was published in 1969.

Details

Melvin Calvin (born April 8, 1911, St. Paul, Minnesota, U.S.—died January 8, 1997, Berkeley, California) was an American biochemist who received the 1961 Nobel Prize for Chemistry for his discovery of the chemical pathways of photosynthesis.

Calvin was the son of immigrant parents. His father was from Kalvaria, Lithuania, so the Ellis Island immigration authorities renamed him Calvin; his mother was from Russian Georgia. Soon after his birth, the family moved to Detroit, Michigan, where Calvin showed an early interest in science, especially chemistry and physics. In 1927 he received a full scholarship from the Michigan College of Mining and Technology (now Michigan Technological University) in Houghton, where he was the school’s first chemistry major. Few chemistry courses were offered, so he enrolled in mineralogy, geology, paleontology, and civil engineering courses, all of which proved useful in his later interdisciplinary scientific research. Following his sophomore year, he interrupted his studies for a year, earning money as an analyst in a brass factory.

Calvin earned a bachelor’s degree in 1931, and then he attended the University of Minnesota in Minneapolis, from which he received a doctorate in 1935 with a dissertation on the electron affinity of halogen atoms. With a Rockefeller Foundation grant, he researched coordination catalysis, activation of molecular hydrogen, and metalloporphyrins (porphyrin and metal compounds) at the University of Manchester in England with Michael Polanyi, who introduced him to the interdisciplinary approach. In 1937 Calvin joined the faculty of the University of California, Berkeley, as an instructor. (He was the first chemist trained elsewhere to be hired by the school since 1912.) He rose through the ranks to become director (1946) of the bioorganic chemistry group at the school’s Lawrence Radiation Laboratory (now the Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory), director of the Laboratory of Chemical Biodynamics (1963), associate director of Lawrence Livermore (1967), and University Professor of Chemistry (1971).

At Berkeley, Calvin continued his work on hydrogen activation and began work on the colour of organic compounds, leading him to study the electronic structure of organic molecules. In the early 1940s, he worked on molecular genetics, proposing that hydrogen bonding is involved in the stacking of nucleic acid bases in chromosomes. During World War II, he worked on cobalt complexes that bond reversibly with oxygen to produce an oxygen-generating apparatus for submarines or destroyers. In the Manhattan Project, he employed chelation and solvent extraction to isolate and purify plutonium from other fission products of uranium that had been irradiated. Although not developed in time for wartime use, his technique was later used for laboratory separations.

In 1942 Calvin married Genevieve Jemtegaard, with later Nobel chemistry laureate Glenn T. Seaborg as best man. The married couple collaborated on an interdisciplinary project to investigate the chemical factors in the Rh blood group system. Genevieve was a juvenile probation officer, but, according to Calvin’s autobiography, “she spent a great deal of time actually in the laboratory working with the antigenic material. This was her first chemical laboratory experience but not her last by any means.” Together they helped to determine the structure of one of the Rh antigens, which they named elinin for their daughter Elin. Following the oil embargo after the 1973 Arab-Israeli War, they sought suitable plants, e.g., genus Euphorbia, to convert solar energy to hydrocarbons for fuel, but the project failed to be economically feasible.

In 1946 Calvin began his Nobel prize-winning work on photosynthesis. After adding carbon dioxide with trace amounts of radioactive carbon-14 to an illuminated suspension of the single-cell green alga Chlorella pyrenoidosa, he stopped the alga’s growth at different stages and used paper chromatography to isolate and identify the minute quantities of radioactive compounds. This enabled him to identify most of the chemical reactions in the intermediate steps of photosynthesis—the process in which carbon dioxide is converted into carbohydrates. He discovered the “Calvin cycle,” in which the “dark” photosynthetic reactions are impelled by compounds produced in the “light” reactions that occur on absorption of light by chlorophyll to yield oxygen. Also using isotopic tracer techniques, he followed the path of oxygen in photosynthesis. This was the first use of a carbon-14 tracer to explain a chemical pathway.

Calvin’s research also included work on electronic, photoelectronic, and photochemical behaviour of porphyrins; chemical evolution and organic geochemistry, including organic constituents of lunar rocks for the U.S. National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA); free radical reactions; the effect of deuterium (“heavy hydrogen”) on biochemical reactions; chemical and viral carcinogenesis; artificial photosynthesis (“synthetic chloroplasts”); radiation chemistry; the biochemistry of learning; brain chemistry; philosophy of science; and processes leading to the origin of life.

Calvin’s bioorganic group eventually required more space, so he designed the new Laboratory of Chemical Biodynamics (the “Roundhouse” or “Calvin Carousel”). This circular building contained open laboratories and numerous windows but few walls to encourage the interdisciplinary interaction that he had carried out with his photosynthesis group at the old Radiation Laboratory. He directed this laboratory until his mandatory age retirement in 1980, when it was renamed the Melvin Calvin Laboratory. Although officially retired, he continued to come to his office until 1996 to work with a small research group.

Calvin was the author of more than 600 articles and 7 books, and he was the recipient of several honorary degrees from U.S. and foreign universities. His numerous awards included the Priestley Medal (1978), the American Chemical Society’s highest award, and the U.S. National Medal of Science (1989), the highest U.S. civilian scientific award.

It appears to me that if one wants to make progress in mathematics, one should study the masters and not the pupils. - Niels Henrik Abel.

Nothing is better than reading and gaining more and more knowledge - Stephen William Hawking.

Offline