Math Is Fun Forum

You are not logged in.

- Topics: Active | Unanswered

#201 Re: Jai Ganesh's Puzzles » Doc, Doc! » 2025-11-04 14:58:06

Hi,

#2516. What does the medical term Leptomeningeal cancer mean?

#202 Jokes » Beverage Jokes - III » 2025-11-04 14:16:14

- Jai Ganesh

- Replies: 0

Q: What has eight arms and an IQ of 60?

A: Four guys drinking Bud Light and watching a football game!

* * *

Q: When do women drink alcohol?

A: Wine O'Clock.

* * *

Q: When does it rain money?

A: When there is "change" in the weather.

* * *

Q: What do you say when you're gonna drunk dial someone?

A: Al-cohol you.

* * *

Q: If H20 is water what is H204?

A: Drinking, bathing, washing, swimming. . .

* * *

#203 Re: Jai Ganesh's Puzzles » 10 second questions » 2025-11-04 14:07:43

Hi,

#9795.

#204 Re: Jai Ganesh's Puzzles » Oral puzzles » 2025-11-04 13:53:43

Hi,

#6290.

#205 Re: Exercises » Compute the solution: » 2025-11-04 13:41:19

Hi,

2638.

#206 This is Cool » Carbonic Acid » 2025-11-03 21:45:49

- Jai Ganesh

- Replies: 0

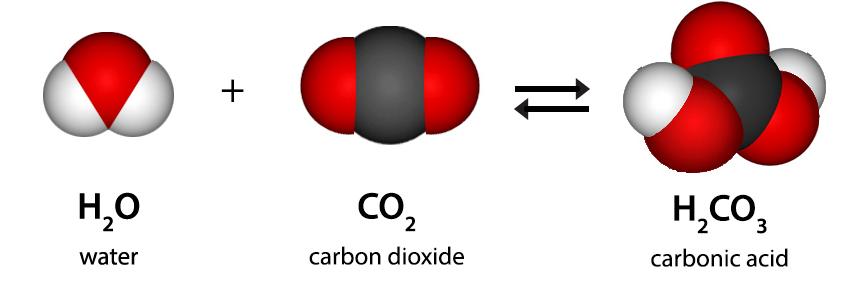

Carbonic Acid

Gist

Carbonic acid (H2CO3) is a weak acid formed when carbon dioxide (CO2)) dissolves in water. It is an unstable compound that can dissociate into a hydrogen ion (H+) and a bicarbonate ion (HCO3-), and it plays a critical role in regulating blood pH in the human body. Carbonic acid is also found in carbonated beverages and is responsible for weathering limestone.

Carbonic acid is used in the food and beverage industry for carbonating soft drinks, wine, and sparkling water; in medicine for its role as a blood buffer and for certain topical treatments; and in industrial applications for pH control in water treatment, as a cleaning agent, and in the production of other chemicals.

Summary

Carbonic acid is a chemical compound with the chemical formula H2CO3. The molecule rapidly converts to water and carbon dioxide in the presence of water. However, in the absence of water, it is quite stable at room temperature. The interconversion of carbon dioxide and carbonic acid is related to the breathing cycle of animals and the acidification of natural waters.

In biochemistry and physiology, the name "carbonic acid" is sometimes applied to aqueous solutions of carbon dioxide. These chemical species play an important role in the bicarbonate buffer system, used to maintain acid–base homeostasis.

Terminology in biochemical literature

In chemistry, the term "carbonic acid" strictly refers to the chemical compound with the formula H2CO3. Some biochemistry literature effaces the distinction between carbonic acid and carbon dioxide dissolved in extracellular fluid.

In physiology, carbon dioxide excreted by the lungs may be called volatile acid or respiratory acid.

Details

Carbonic acid, (H2CO3) is a compound of the elements hydrogen, carbon, and oxygen. It is formed in small amounts when its anhydride, carbon dioxide (CO2), dissolves in water.

The predominant species are simply loosely hydrated CO2 molecules. Carbonic acid can be considered to be a diprotic acid from which two series of salts can be formed—namely, hydrogen carbonates.

However, the acid-base behaviour of carbonic acid depends on the different rates of some of the reactions involved, as well as their dependence on the pH of the system.

Between pH values of 8 and 10, all the above equilibrium reactions are significant.

Carbonic acid plays a role in the assembly of caves and cave formations like stalactites and stalagmites. The largest and most common caves are those formed by dissolution of limestone or dolomite by the action of water rich in carbonic acid derived from recent rainfall. The calcite in stalactites and stalagmites is derived from the overlying limestone near the bedrock/soil interface. Rainwater infiltrating through the soil absorbs carbon dioxide from the carbon dioxide-rich soil and forms a dilute solution of carbonic acid. When this acid water reaches the base of the soil, it reacts with the calcite in the limestone bedrock and takes some of it into solution. The water continues its downward course through narrow joints and fractures in the unsaturated zone with little further chemical reaction. When the water emerges from the cave roof, carbon dioxide is lost into the cave atmosphere, and some of the calcium carbonate is precipitated. The infiltrating water acts as a calcite pump, removing it from the top of the bedrock and redepositing it in the cave below.

Carbonic acid is important in the transport of carbon dioxide in the blood. Carbon dioxide enters blood in the tissues because its local partial pressure is greater than its partial pressure in blood flowing through the tissues. As carbon dioxide enters the blood, it combines with water to form carbonic acid, which dissociates into hydrogen ions (H+) and bicarbonate ions (HCO3-). Blood acidity is minimally affected by the released hydrogen ions because blood proteins, especially hemoglobin, are effective buffering agents. (A buffer solution resists change in acidity by combining with added hydrogen ions and, essentially, inactivating them.) The natural conversion of carbon dioxide to carbonic acid is a relatively slow process; however, carbonic anhydrase, a protein enzyme present inside the red blood cell, catalyzes this reaction with sufficient rapidity that it is accomplished in only a fraction of a second. Because the enzyme is present only inside the red blood cell, bicarbonate accumulates to a much greater extent within the red cell than in the plasma. The capacity of blood to carry carbon dioxide as bicarbonate is enhanced by an ion transport system inside the red blood cell membrane that simultaneously moves a bicarbonate ion out of the cell and into the plasma in exchange for a chloride ion. The simultaneous exchange of these two ions, known as the chloride shift, permits the plasma to be used as a storage site for bicarbonate without changing the electrical charge of either the plasma or the red blood cell. Only 26 percent of the total carbon dioxide content of blood exists as bicarbonate inside the red blood cell, while 62 percent exists as bicarbonate in plasma; however, the bulk of bicarbonate ions is first produced inside the cell, then transported to the plasma. A reverse sequence of reactions occurs when blood reaches the lung, where the partial pressure of carbon dioxide is lower than in the blood.

Additional Information

Carbonic Acid is an inorganic, weak, and unstable acid. The molecule of Carbonic Acid consists of one carbon atom, two hydrogen atoms, and three oxygen atoms. Carbonic Acid is also referred to as a respiratory acid as it is the only acid that is exhaled in the gaseous state by human lungs.

Carbonic acid is studied majorly in various fields of science because of its vast applications and uses. It helps improve marine life due to its natural process of ocean acidification. It is essential for the human body as well.

What is Carbonic Acid?

Carbonic acid is a chemical compound made of carbon dioxide, oxygen, and hydrogen as its elements. It is a weak acid with the chemical formula H2CO3. It is formed when carbon dioxide is dissolved in water. Carbonic acid is a diprotic acid, which means it can form two types of salts: carbonate and bicarbonate. Carbonic Acid is also known as dihydrogen carbonate (because it is made of two hydrogen atoms and a carbonate ion), aerial acid (or acid of air), Oxidocarboxylic acid, Hydroxyformic acid, etc.

It was discovered by the French chemist Antoine Lavoisier in the late 18th century. He found that when carbon dioxide reacts with water an acidic solution is formed which he named as carbonic acid.

Formula of Carbonic Acid

The compound of carbonic acid consists of one carbon atom, two hydrogen atoms, and three oxygen atoms. It can also be represented as OC(OH)2 due to the presence of a carbon-oxygen double bond.

Structure of Carbonic Acid

Carbonic acid consists of a carboxyl functional group along with a hydroxyl group. The structure of carbonic acids consists of one carbon-oxygen double bond and further, this carbon is single bonded with two hydroxyl groups (OH).

Preparation of Carbonic Acid

When strong acid reacts with calcium carbonate, carbon dioxide gas is evolved which when dissolved in water, Carbonic acid is formed.

Properties of Carbonic Acid

Carbonic acid has a variety of properties which are classified into physical and chemical properties. The physical and chemical properties of carbonic acid are described below:

Physical Properties of Carbonic Acid

* State: Carbonic Acid generally occurs as a solution, but according to recent research it was found that Carbonic acid is also being prepared in a solid state by NASA scientists.

* Odor: Carbonic Acid are generally odorless.

* pKa value: The pKa value of Carbonic acid is 6.35. The pKa value is inversely proportional to the acidity of the compound. Hence, carbonic acid is termed under weak acid.

* Boiling Point: The boiling point of carbonic acid is around 127° Celsius.

* Melting Point: The melting point of carbonic acid is around -53° Celsius.

* Density: Carbonic acid has a density of around 1.668 grams per cubic centimeter.

* Molecular weight: The molecular weight of Carbonic acid is 62.024 g/mol.

* Conjugate base: The conjugate bases of Carbonic acid are bicarbonate and carbonate.

Chemical Properties of Carbonic Acid

* Stability: Carbonic acids are unstable under normal circumstances. However, they can be stabilized under high pressure and high temperatures.

* pH: Being a weak acidic, carbonic acid has a pH value of around 4.68

* Diprotic acid: It is a diprotic acid, i.e. it can form two types of salts namely carbonate and bicarbonate.

* Dissociation reaction: In the presence of water, Carbonic acid can partially dissociate into bicarbonate ions (HCO3-) and hydrogen ions (H+).

* Reaction with base: Carbonic acids form bicarbonate salt when reacted with a moderate amount of base and it form carbonate salts if reacted with excess amount of base.

* Decomposition reaction: Carbonic acid can easily decompose into carbon dioxide and water. However, this reaction is reversible under suitable conditions.

Uses of Carbonic Acid

* Carbonated Drinks: Carbonic acid provides the fizzy and bubbly taste in carbonated drinks like sparkling water, sodas, soft drinks, beer, champagne and other carbonated beverages

* Buffering System: Carbonic acid acts as a buffer system in human bodies which helps in maintaining the pH balance in the blood.

* pH regulation: Carbonic acid is also useful in regulating the pH level of water in swimming pools and in regulating pH balance in various other industrial processes.

* Medicinal uses: It is used in medications to balance acid-base levels in the body and in ointments to treat various fungal infections like ringworm. It is also consumed to induce vomiting (when required).

* pH indicator: Carbonic acid is used as a pH indicator to check whether the solution is acidic or basic.

* Precipitation: Carbonic acid is used as a solvent in the precipitation of various ammonium salts like ammonium persulfate.

Cleansing agent: Carbonic acid is also used as a cleaning agent to clean contact lenses.

#207 Science HQ » Chromosome » 2025-11-03 16:46:26

- Jai Ganesh

- Replies: 0

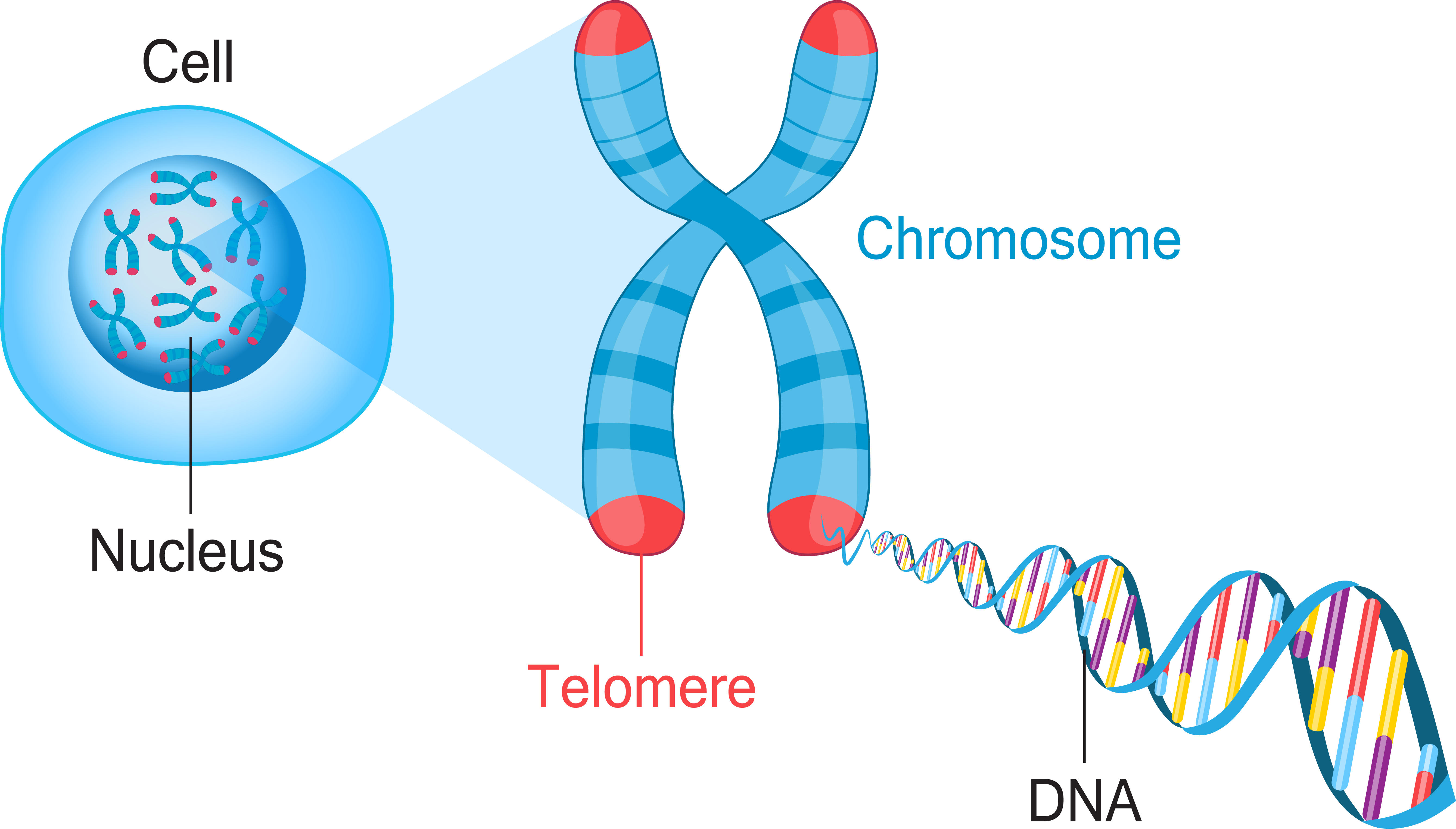

Chromosome

Gist

A chromosome is a thread-like structure made of proteins and a single molecule of DNA that carries the genetic information of an organism. Located in the nucleus of cells, chromosomes are a highly organized way to package the DNA, which is a very long molecule. Humans typically have 46 chromosomes in 23 pairs, with 22 pairs of autosomes and one pair of sex chromosomes (X and Y).

Chromosomes are long strings of DNA wrapped around proteins to make them compact. They're a way for cells to organize and store your DNA. Humans typically have 23 pairs of chromosomes for a total of 46 chromosomes. The first 22 are called autosomes and the last pair are sex chromosomes.

Summary

Chromosomes are threadlike structures made of protein and a single molecule of DNA that serve to carry the genomic information from cell to cell. In plants and animals (including humans), chromosomes reside in the nucleus of cells. Humans have 22 pairs of numbered chromosomes (autosomes) and one pair of sex chromosomes (XX or XY), for a total of 46. Each pair contains two chromosomes, one coming from each parent, which means that children inherit half of their chromosomes from their mother and half from their father. Chromosomes can be seen through a microscope when the nucleus dissolves during cell division.

Chromosomes vary in number and shape among living organisms. Most bacteria have one or two circular chromosomes. Humans, along with other animals and plants, have linear chromosomes . In fact, each species of plants and animals has a set number of chromosomes. A fruit fly, for example, has four pairs of chromosomes, while a rice plant has 12 and a dog, 39. In humans, the twenty-third pair is the sex chromosomes, while the first 22 pairs are called autosomes. Typically, biologically female individuals have two X chromosomes (XX) while those who are biologically male have one X and one Y chromosome (XY). However, there are exceptions to these rules. Chromosomes are also different sizes. The human X chromosome is about three times larger than the human Y chromosome, containing about 900 genes, while the Y chromosome has about 55 genes. The unique structure of chromosomes keeps DNA tightly wound around spool-like proteins, called histones. Without such packaging, DNA molecules would be too long to fit inside cells! For example, if all of the DNA molecules in a single human cell were unwound from their histones and placed end-to-end, they would stretch 6 feet.

Details

A chromosome is a package of DNA containing part or all of the genetic material of an organism. In most chromosomes, the very long thin DNA fibers are coated with nucleosome-forming packaging proteins; in eukaryotic cells, the most important of these proteins are the histones. Aided by chaperone proteins, the histones bind to and condense the DNA molecule to maintain its integrity. These eukaryotic chromosomes display a complex three-dimensional structure that has a significant role in transcriptional regulation.

Normally, chromosomes are visible under a light microscope only during the metaphase of cell division, where all chromosomes are aligned in the center of the cell in their condensed form. Before this stage occurs, each chromosome is duplicated (S phase), and the two copies are joined by a centromere—resulting in either an X-shaped structure if the centromere is located equatorially, or a two-armed structure if the centromere is located distally; the joined copies are called 'sister chromatids'. During metaphase, the duplicated structure (called a 'metaphase chromosome') is highly condensed and thus easiest to distinguish and study. In animal cells, chromosomes reach their highest compaction level in anaphase during chromosome segregation.

Chromosomal recombination during meiosis and subsequent sexual reproduction plays a crucial role in genetic diversity. If these structures are manipulated incorrectly, through processes known as chromosomal instability and translocation, the cell may undergo mitotic catastrophe. This will usually cause the cell to initiate apoptosis, leading to its own death, but the process is occasionally hampered by cell mutations that result in the progression of cancer.

The term 'chromosome' is sometimes used in a wider sense to refer to the individualized portions of chromatin in cells, which may or may not be visible under light microscopy. In a narrower sense, 'chromosome' can be used to refer to the individualized portions of chromatin during cell division, which are visible under light microscopy due to high condensation.

Additional Information

A chromosome is a microscopic threadlike part of the cell that carries hereditary information in the form of genes. A defining feature of any chromosome is its compactness. For instance, the 46 chromosomes found in human cells have a combined length of 200 nm (1 nm = {10}^{-9} metre); if the chromosomes were to be unraveled, the genetic material they contain would measure roughly 2 metres (about 6.5 feet) in length. The compactness of chromosomes plays an important role in helping to organize genetic material during cell division and enabling it to fit inside structures such as the nucleus of a cell, the average diameter of which is about 5 to 10 μm (1 μm = 0.00l mm, or 0.000039 inch), or the polygonal head of a virus particle, which may be in the range of just 20 to 30 nm in diameter.

The structure and location of chromosomes are among the chief differences between viruses, prokaryotes, and eukaryotes. The nonliving viruses have chromosomes consisting of either DNA (deoxyribonucleic acid) or RNA (ribonucleic acid); this material is very tightly packed into the viral head. Among organisms with prokaryotic cells (i.e., bacteria and blue-green algae), chromosomes consist entirely of DNA. The single chromosome of a prokaryotic cell is not enclosed within a nuclear membrane. Among eukaryotes, the chromosomes are contained in a membrane-bound cell nucleus. The chromosomes of a eukaryotic cell consist primarily of DNA attached to a protein core. They also contain RNA. The remainder of this article pertains to eukaryotic chromosomes.

Every eukaryotic species has a characteristic number of chromosomes (chromosome number). In species that reproduce asexually, the chromosome number is the same in all the cells of the organism. Among sexually reproducing organisms, the number of chromosomes in the body (somatic) cells is diploid (2n; a pair of each chromosome), twice the haploid (1n) number found in the sex cells, or gametes. The haploid number is produced during meiosis. During fertilization, two gametes combine to produce a zygote, a single cell with a diploid set of chromosomes.

Somatic cells reproduce by dividing, a process called mitosis. Between cell divisions the chromosomes exist in an uncoiled state, producing a diffuse mass of genetic material known as chromatin. The uncoiling of chromosomes enables DNA synthesis to begin. During this phase, DNA duplicates itself in preparation for cell division.

Following replication, the DNA condenses into chromosomes. At this point, each chromosome actually consists of a set of duplicate chromatids that are held together by the centromere. The centromere is the point of attachment of the kinetochore, a protein structure that is connected to the spindle fibres (part of a structure that pulls the chromatids to opposite ends of the cell). During the middle stage in cell division, the centromere duplicates, and the chromatid pair separates; each chromatid becomes a separate chromosome at this point. The cell divides, and both of the daughter cells have a complete (diploid) set of chromosomes. The chromosomes uncoil in the new cells, again forming the diffuse network of chromatin.

Among many organisms that have separate sexes, there are two basic types of chromosomes: sex chromosomes and autosomes. Autosomes control the inheritance of all the characteristics except the sex-linked ones, which are controlled by the sex chromosomes. Humans have 22 pairs of autosomes and one pair of sex chromosomes. All act in the same way during cell division.

Chromosome breakage is the physical breakage of subunits of a chromosome. It is usually followed by reunion (frequently at a foreign site, resulting in a chromosome unlike the original). Breakage and reunion of homologous chromosomes during meiosis are the basis for the classical model of crossing over, which results in unexpected types of offspring of a mating.

#208 Re: Jai Ganesh's Puzzles » General Quiz » 2025-11-03 16:24:24

Hi,

#10645. What does the term in Geography Chorology mean?

#10646. What does the term in Geography Choropleth map mean?

#209 Re: Jai Ganesh's Puzzles » English language puzzles » 2025-11-03 16:09:42

Hi,

#5841. What does the noun foreword mean?

#5842. What does the verb (used with object) forfeit mean?

#210 Re: Dark Discussions at Cafe Infinity » crème de la crème » 2025-11-03 15:56:26

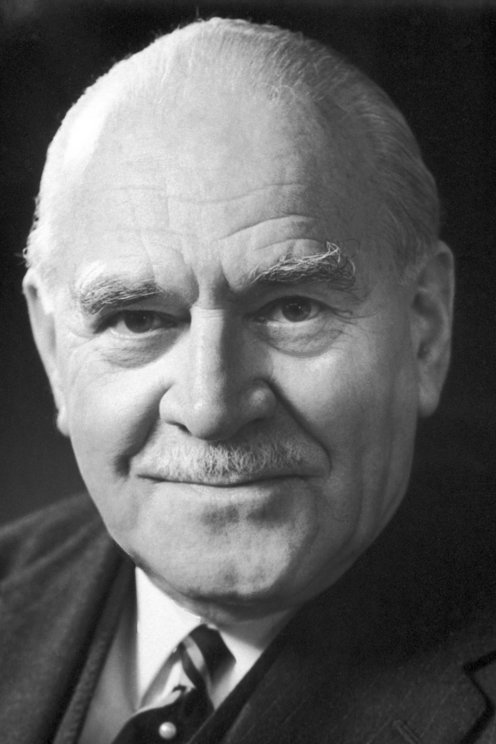

2383) Ronald George Wreyford Norrish

Gist:

Work

During chemical reactions, atoms and molecules regroup and form new constellations. Chemical reactions are affected by heat and light, among other things. The sequence of events can proceed very quickly. At the end of the 1940s, Ronald Norrish and George Porter built an extremely powerful lamp that emitted very short bursts of light. The light’s energy triggered reactions among the molecules or split them into parts that were inclined to react. By registering the light spectrums that are characteristic for different substances, the progress of the reaction could be monitored.

Summary

Ronald George Wreyford Norrish (born Nov. 9, 1897, Cambridge, Cambridgeshire, Eng.—died June 7, 1978, Cambridge) was a British chemist who was the corecipient, with fellow Englishman Sir George Porter and Manfred Eigen of West Germany, of the 1967 Nobel Prize for Chemistry. All three were honoured for their studies of very fast chemical reactions.

Norrish did his undergraduate and doctoral work at the University of Cambridge, served as research fellow at Emmanuel College, Cambridge, and directed the university’s physical chemistry department for 28 years. Norrish and Porter, who worked together between 1949 and 1965, used the new technique of flash photolysis to study the intermediate stages involved in extremely rapid chemical reactions. In this technique, a gaseous system in a state of equilibrium is subjected to an ultrashort burst of light that causes photochemical reactions in the gas. A second burst of light is then used to detect and record the changes taking place in the gas before equilibrium is reestablished. Norrish became a professor emeritus in 1963, though he continued to work with individual students and as an industrial consultant.

Details

Ronald George Wreyford Norrish FRS (9 November 1897 – 7 June 1978) was a British chemist who was awarded the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 1967.

Education and early life

Norrish was born in Cambridge and was educated at The Perse School and Emmanuel College, Cambridge. He was a former student of Eric Rideal. From an early age he was interested in chemistry, walking up and down Cambridge University chemical laboratory admiring all the equipment. His father encouraged him to construct and equip a small laboratory in his garden shed in his garden and supplied all the chemicals he needed to conduct experiments. This apparatus now forms part of the Science Museum collections - reference shows copper water tank. He used to enter competitions for the analysis of mixtures sent round by the Pharmaceutical Journal and often won prizes. In 1915 Norrish won a Foundation Scholarship to Emmanuel College, but by adding a little to his age joined the Royal Field Artillery and served as a Lieutenant, first in Ireland and then on the Western Front.

Career and research

Norrish was a prisoner in World War I and later commented, with sadness, that many of his contemporaries and potential competitors at Cambridge had not survived the War. Military records show that 2nd Lieutenant Norrish of the Royal Artillery went missing (captured) on 21 March 1918.

Norrish rejoined Emmanuel College as a Research Fellow in 1925 and later became Head of the Department of Physical Chemistry at the University of Cambridge.

The skill which Norrish displayed in his laboratory work problems marked him out amongst his contemporaries as an unusually gifted and energetic experimentalist, capable of making significant advances in photo-chemistry and gas kinetics.

Awards and honours

Norrish was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society (FRS) in 1936. As a result of the development of flash photolysis, Norrish was awarded the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 1967 along with Manfred Eigen and George Porter for their study of extremely fast chemical reactions. One of his accomplishments is the development of the Norrish reaction.

At Cambridge, Norrish supervised Rosalind Franklin, future DNA researcher and colleague of James Watson and Francis Crick, and experienced some conflict with her.

#211 Re: This is Cool » Miscellany » 2025-11-03 15:36:16

2435} Polyvinyl Chloride

Gist

Polyvinyl chloride (PVC) is a versatile synthetic plastic polymer produced from vinyl chloride monomers, widely used in applications from construction (pipes, window frames) to healthcare (IV bags, tubing) and everyday products. It can be made rigid or flexible by adding plasticizers, and is valued for its durability, low cost, and resistance to chemicals, corrosion, and fire.

Polyvinyl chloride (PVC) is used in a wide variety of products due to its versatility as a rigid or flexible material, including construction (pipes, window frames), electrical insulation, medical devices (IV bags, tubing), packaging, and consumer goods like flooring and raincoats. Its use in building and construction accounts for about three-quarters of all vinyl production, taking advantage of its durability, strength, and resistance to moisture and corrosion.

Summary

Polyvinyl chloride (alternatively: poly(vinyl chloride), colloquial: vinyl or polyvinyl; abbreviated: PVC) is the world's third-most widely produced synthetic polymer of plastic (after polyethylene and polypropylene). About 40 million tons of PVC are produced each year.

PVC comes in rigid (sometimes abbreviated as RPVC) and flexible forms. Rigid PVC is used in construction for pipes, doors and windows. It is also used in making plastic bottles, packaging, and bank or membership cards. Adding plasticizers makes PVC softer and more flexible. It is used in plumbing, electrical cable insulation, flooring, signage, phonograph records, inflatable products, and in rubber substitutes. With cotton or linen, it is used in the production of canvas.

Polyvinyl chloride is a white, brittle solid. It is soluble in ketones, chlorinated solvents, dimethylformamide, THF and DMAc.

Chlorinated PVC

PVC can be usefully modified by chlorination, which increases its chlorine content to or above 67%. Chlorinated polyvinyl chloride, (CPVC), as it is called, is produced by chlorination of aqueous solution of suspension PVC particles followed by exposure to UV light which initiates the free-radical chlorination.

Adhesives

Flexible plasticized PVC can be glued with special adhesives often referred to as solvent cement as solvents are the main ingredients. PVC or polyurethane resin may be added to increase viscosity, allow the adhesive to fill gaps, to accelerate setting and to reduce shrinkage and internal stresses. Viscosity can be further increased by adding fumed silica as a filler. As molecules are mobilized by the solvents and migrating PVC polymers are interlinking at the joint the process is also referred to as welding or cold welding. PVC can be made with a variety of plasticizers. Plasticizer migration from the vinyl part into the adhesive can degrade the strength of the joint. If this is of concern the adhesives should be tested for their resistance to the plasticizer. Nitrile rubber adhesives are often used with flexible PVC film as they are known to be resistant to plasticizers. Some epoxy adhesive formulations have provide good adhesion to flexible PVC substrate. Typical formulations of common solvent cement may contain 10–50% ethyl acetate, 8–16% acetone, 12–50% butanone (methyl ethyl ketone, MEK), 0–18% methyl acetate, 12–30% polyurethane and 0-10% toluene. Alternatively methyl isobutyl ketone or tetrahydrofuran may be added as solvents, tin organic compounds as stabilizer and dioctylphthalate as a plasticizer.

Details

PVC, a synthetic resin made from the polymerization of vinyl chloride. Second only to polyethylene among the plastics in production and consumption, PVC is used in an enormous range of domestic and industrial products, from raincoats and shower curtains to window frames and indoor plumbing. A lightweight, rigid plastic in its pure form, it is also manufactured in a flexible “plasticized” form.

Vinyl chloride (CH2=CHCl), also known as chloroethylene, is most often obtained by reacting ethylene with oxygen and hydrogen chloride over a copper catalyst. It is a toxic and carcinogenic gas that is handled under special protective procedures. PVC is made by subjecting vinyl chloride to highly reactive compounds known as free-radical initiators. Under the action of the initiators, the double bond in the vinyl chloride monomers (single-unit molecules) is opened, and one of the resultant single bonds is used to link together thousands of vinyl chloride monomers to form the repeating units of polymers (large, multiple-unit molecules).

PVC was prepared by the French chemist Henri Victor Regnault in 1835 and then by the German chemist Eugen Baumann in 1872, but it was not patented until 1912, when another German chemist, Friedrich Heinrich August Klatte, used sunlight to initiate the polymerization of vinyl chloride. Commercial application of the plastic was at first limited by its extreme rigidity; however, in 1926, while trying to dehydrohalogenate PVC in a high-boiling solvent in order to obtain an unsaturated polymer that might bond rubber to metal, Waldo Lunsbury Semon, working for the B.F. Goodrich Company in the United States, produced what is now called plasticized PVC. The discovery of this flexible, inert product was responsible for the commercial success of the polymer. Under the trademark Koroseal, Goodrich made the plastic into shock-absorber seals, electric-wire insulation, and coated cloth products. One of the best-known applications of the plastic was initiated in 1930, when the Union Carbide and Carbon Corporation (later the Union Carbide Corporation) introduced Vinylite, a copolymer of vinyl chloride and vinyl acetate that became the standard material of long-playing phonograph records.

Pure PVC finds application in the construction trades, where its rigidity, strength, and flame resistance are useful in pipes, conduits, siding, window frames, and door frames. It is also blow-molded into clear, transparent bottles. Because of its rigidity, it must be extruded or molded above 100 °C (212 °F)—a temperature high enough to initiate chemical decomposition (in particular, the emission of hydrogen chloride [HCl]). Decomposition can be reduced by the addition of stabilizers, which are mainly compounds of metals such as cadmium, zinc, tin, or lead.

In order to arrive at a product that remains flexible, especially at low temperatures, most PVC is heated and mixed with plasticizers, which are sometimes added in concentrations as high as 50 percent. The most commonly used plasticizer is the compound di-2-ethylhexyl phthalate (DEHP), also known as dioctyl phthalate (DOP). Plasticized PVC is familiar to consumers as floor tile, garden hose, imitation leather upholstery, and shower curtains.

Very fine particles of PVC can be dispersed in plasticizer in excess of the amount used to make plasticized PVC (e.g., 50 percent or more), and this suspension can be heated until the polymer particles dissolve. The resultant fluid, called a plastisol, will remain liquid even after cooling but will solidify into a gel upon reheating. Plastisols can be made into products by being spread on fabric or cast into molds. Flexible gloves can be made by dipping a hand-shaped form into plastisol, and hollow objects such as overshoes can be made by casting plastisol into a mold, pouring off the excess, and solidifying the material remaining on the walls of the mold.

PVC has been an occasional object of controversy since a link between vinyl chloride monomer and cancer was established in 1973. Environmentalists and health advocates raised concerns over the possible ill effects of exposure to substances such as residual vinyl chloride monomer, hydrogen chloride, organometallic stabilizers, and phthalate plasticizers. Industry officials maintain that these substances are scrupulously controlled and are released from PVC in trace amounts that have not been proved harmful.

Rigid PVC is typically made into durable structural products such as window casings and home siding, which are not frequently recycled. PVC bottles and containers, however, can be recycled into products such as drainage pipe and traffic cones. The recycling code number of PVC is #3.

Additional Information

Polyvinyl chloride is one of the cheapest and most widely used plastics globally. It is a thermoplastic having good resistance to alkalis, salts, and highly polar solvents, and it is flame retardant due to the presence of chlorine in the structure. The presence of chlorine makes it flame retardant. But PVC is not thermally stable at higher temperatures. Plasticizers are added to PVC for safe processing due to its thermal instability at high temperature . In automobile industry, it is used for the fabrication of internal lining, protective covering of bottom flooring cars, and coating of electric cables in vehicles. It has excellent properties like good flexibility, flame retardancy, good thermal stability and high gloss and low lead content, diversity of manufacturing procedures, and easy to paste, print and weld . It is used for the large scale production of cable insulations, equipment parts, pipes, laminated materials, and in fiber manufacture. The PVC polymer can be blow molded, calendared, injection molded, and compression molded to form a large varieties of products. Depending upon the amount and type of plasticizers used, the product formed from the PVC is either rigid or flexible. Its vinyl content that gives good tensile strength. It has good resistant to chemical and solvent attack. Colored or transparent material is also available. It is used in automobile instrument panels and sheathing of electrical cables.

#212 Re: Jai Ganesh's Puzzles » Doc, Doc! » 2025-11-03 14:52:23

Hi,

#2515. What does the medical term Apraxia mean?

#213 Dark Discussions at Cafe Infinity » Code Quotes - I » 2025-11-03 14:44:25

- Jai Ganesh

- Replies: 0

Code Quotes - I

1. Our heritage and ideals, our code and standards - the things we live by and teach our children - are preserved or diminished by how freely we exchange ideas and feelings. - Walt Disney

2. With genetic engineering, we will be able to increase the complexity of our DNA, and improve the human race. But it will be a slow process, because one will have to wait about 18 years to see the effect of changes to the genetic code. - Stephen Hawking

3. Ought we not to ask the media to agree among themselves a voluntary code of conduct, under which they would not say or show anything which could assist the terrorists' morale or their cause while the hijack lasted. - Margaret Thatcher

4. When I launched the development of the GNU system, I explicitly said the purpose of developing this system is so we can use our computers and have freedom, thus if you use some other free system instead but you have freedom, then it's a success. It's not popularity for our code but it's success for our goal. - Richard Stallman

5. Beware of bugs in the above code; I have only proved it correct, not tried it. - Donald Knuth

6. If we're trying to build a world-class News Feed and a world-class messaging product and a world-class search product and a world-class ad system, and invent virtual reality and build drones, I can't write every line of code. I can't write any lines of code. - Mark Zuckerberg

7. Every aspect of Western culture needs a new code of ethics - a rational ethics - as a precondition of rebirth. - Ayn Rand

8. I basically wrote the code and the specs and documentation for how the client and server talked to each other. - Tim Berners-Lee.

#214 Jokes » Beverage Jokes - II » 2025-11-03 14:22:03

- Jai Ganesh

- Replies: 0

Q: What's the new Pepsi ad slogan?

A: "Cause sometimes they don't have Coke"!

* * *

Q: What's the difference between Amy Winehouse and Captain Morgan?

A: Captain Morgan comes alive when you add coke!

* * *'

Q: What did one water bottle say to another?

A: Water you doing today?

* * *

Q: Did you hear about the guy who got hit in the head with a can of Coke?

A: He was lucky it was a soft drink.

* * *

Q: What did the man with slab of asphalt under his arm order?

A: "A beer please, and one for the road."

* * *

#215 Re: Jai Ganesh's Puzzles » 10 second questions » 2025-11-03 14:07:09

Hi,

#9794.

#216 Re: Jai Ganesh's Puzzles » Oral puzzles » 2025-11-03 13:45:13

Hi,

#6289.

#217 Re: Exercises » Compute the solution: » 2025-11-03 13:39:44

Hi,

2637.

#218 Science HQ » Mitosis » 2025-11-02 20:27:52

- Jai Ganesh

- Replies: 0

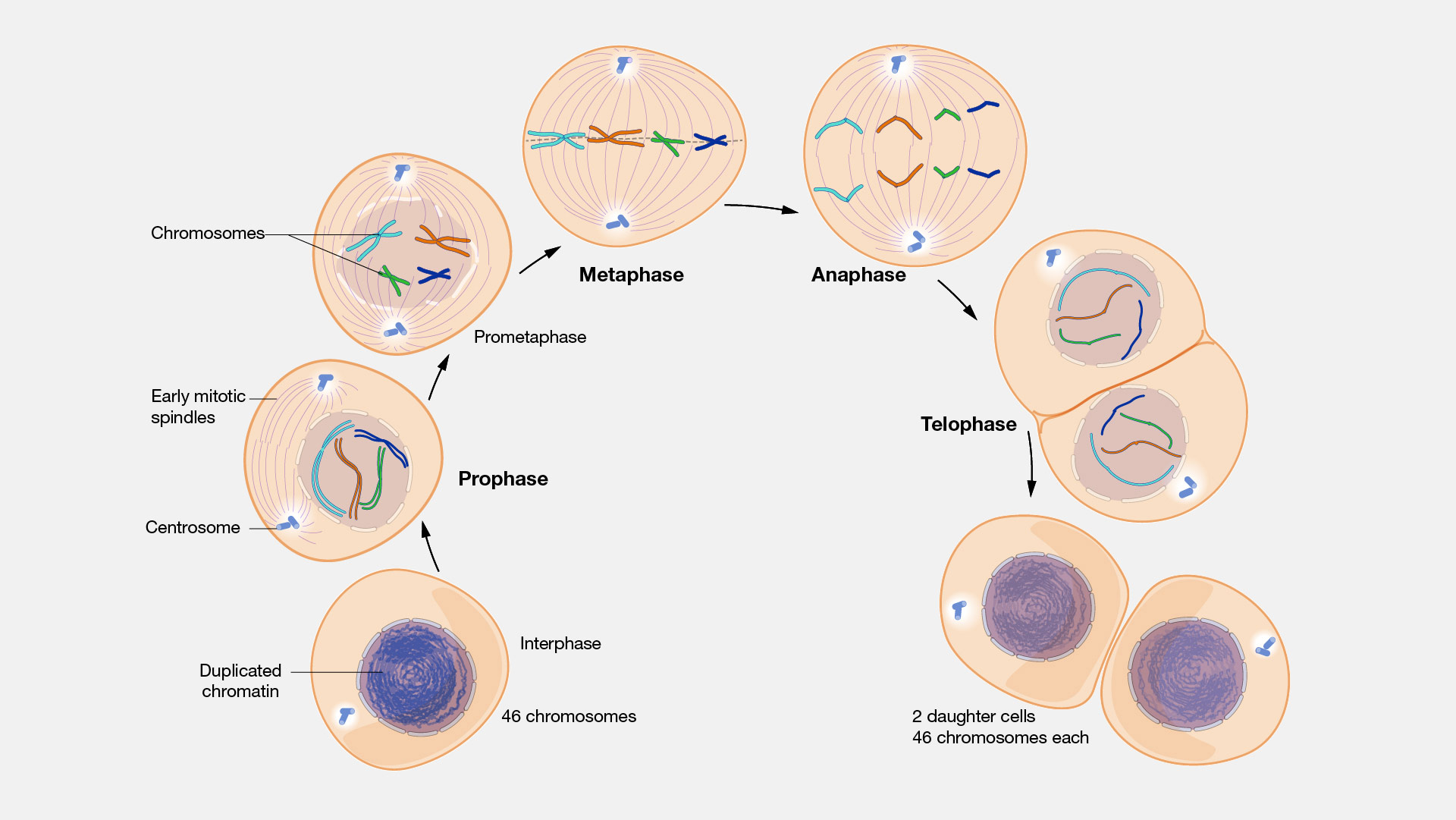

Mitosis

Gist

Mitosis is the process of cell division where a parent cell duplicates its chromosomes and divides to form two genetically identical daughter cells. It involves five main phases—prophase, prometaphase, metaphase, anaphase, and telophase—and is crucial for growth, repair, and asexual reproduction. This process ensures that each new cell receives the same number of chromosomes as the original cell.

Mitosis is important for growth, repair, and reproduction, as it creates genetically identical cells. It is the process by which organisms grow from a single cell into a multicellular being, replaces old or damaged cells (like skin cells), and allows single-celled organisms to reproduce asexually. This ensures that new cells have the exact same genetic information as the parent cell, which is crucial for maintaining the integrity of tissues and the organism as a whole.

Summary

Mitosis is a part of the cell cycle in eukaryotic cells in which replicated chromosomes are separated into two new nuclei. Cell division by mitosis is an equational division which gives rise to genetically identical cells in which the total number of chromosomes is maintained. Mitosis is preceded by the S phase of interphase (during which DNA replication occurs) and is followed by telophase and cytokinesis, which divide the cytoplasm, organelles, and cell membrane of one cell into two new cells containing roughly equal shares of these cellular components. This process ensures that each daughter cell receives an identical set of chromosomes, maintaining genetic stability across cell generations. The different stages of mitosis altogether define the mitotic phase (M phase) of a cell cycle—the division of the mother cell into two daughter cells genetically identical to each other.

The process of mitosis is divided into stages corresponding to the completion of one set of activities and the start of the next. These stages are preprophase (specific to plant cells), prophase, prometaphase, metaphase, anaphase, and telophase. During mitosis, the chromosomes, which have already duplicated during interphase, condense and attach to spindle fibers that pull one copy of each chromosome to opposite sides of the cell. The result is two genetically identical daughter nuclei. The rest of the cell may then continue to divide by cytokinesis to produce two daughter cells. The different phases of mitosis can be visualized in real time, using live cell imaging.

An error in mitosis can result in the production of three or more daughter cells instead of the normal two. This is called tripolar mitosis and multipolar mitosis, respectively. These errors can be the cause of non-viable embryos that fail to implant. Other errors during mitosis can induce mitotic catastrophe, apoptosis (programmed cell death) or cause mutations. Certain types of cancers can arise from such mutations.

Mitosis varies between organisms. For example, animal cells generally undergo an open mitosis, where the nuclear envelope breaks down before the chromosomes separate, whereas fungal cells generally undergo a closed mitosis, where chromosomes divide within an intact cell nucleus. Most animal cells undergo a shape change, known as mitotic cell rounding, to adopt a near spherical morphology at the start of mitosis. Most human cells are produced by mitotic cell division. Important exceptions include the gametes – sperm and egg cells – which are produced by meiosis. Prokaryotes, bacteria and archaea which lack a true nucleus, divide by a different process called binary fission.

Details

Mitosis is a process of cell duplication, or reproduction, during which one cell gives rise to two genetically identical daughter cells. Strictly applied, the term mitosis is used to describe the duplication and distribution of chromosomes, the structures that carry the genetic information.

A brief treatment of mitosis follows.

Prior to the onset of mitosis, the chromosomes have replicated and the proteins that will form the mitotic spindle have been synthesized. Mitosis begins at prophase with the thickening and coiling of the chromosomes. The nucleolus, a rounded structure, shrinks and disappears. The end of prophase is marked by the beginning of the organization of a group of fibres to form a spindle and the disintegration of the nuclear membrane.

The chromosomes, each of which is a double structure consisting of duplicate chromatids, line up along the midline of the cell at metaphase. In anaphase each chromatid pair separates into two identical chromosomes that are pulled to opposite ends of the cell by the spindle fibres. During telophase, the chromosomes begin to decondense, the spindle breaks down, and the nuclear membranes and nucleoli re-form. The cytoplasm of the mother cell divides to form two daughter cells, each containing the same number and kind of chromosomes as the mother cell. The stage, or phase, after the completion of mitosis is called interphase.

Mitosis is absolutely essential to life because it provides new cells for growth and for replacement of worn-out cells. Mitosis may take minutes or hours, depending upon the kind of cells and species of organisms. It is influenced by time of day, temperature, and chemicals.

Additional Information

Mitosis is the process by which a cell replicates its chromosomes and then segregates them, producing two identical nuclei in preparation for cell division. Mitosis is generally followed by equal division of the cell’s content into two daughter cells that have identical genomes.

We can think about mitosis like making a copy of an instruction manual. Copy each page, then give one copy to each of two people. In mitosis, a cell copies each chromosome, then gives one copy to each of two daughter cells. With our instruction manual example, it is really important that each person gets one copy of every page. We don't want to accidentally give one person two copies of page four and one person zero copies of page four. And the copies need to be perfect. No misspellings, no deletions. Otherwise, we might not be able to follow the instructions and things could go wrong. This is also true with mitosis. We need each of our cells to receive exactly one copy of each chromosome, and each copy needs to be perfect, no mistakes, or the cells may have trouble following the genetic instructions. Fortunately, our cells have amazing systems to copy chromosomes almost perfectly and to make sure that one copy goes to each daughter cell. Still, very rarely mistakes in copying or dividing chromosomes are made, and these mistakes can have negative consequences for cells and for people.

#219 Re: Dark Discussions at Cafe Infinity » crème de la crème » 2025-11-02 17:32:54

2382) Manfred Eigen

Gist:

Work

During chemical reactions, atoms and molecules regroup and form new constellations. Chemical reactions are affected by heat and light, among other things. The sequence of events can proceed very quickly. In 1953 Manfred Eigen introduced high-frequency sound waves as a way of bringing about rapid chemical reactions and processes, such as the dissolving of a salt in a solvent. The speed of the reaction could be calculated based the sound waves’ energy. He also studied how electrical voltage affects chemical processes.

Summary

Manfred Eigen (born May 9, 1927, Bochum, Germany—died February 6, 2019) was a German physicist who was corecipient, with Ronald George Wreyford Norrish and George Porter, of the 1967 Nobel Prize for Chemistry for work on extremely rapid chemical reactions.

Eigen was educated in physics and chemistry at the University of Göttingen (Ph.D., 1951). He worked at the university’s Institute of Physical Chemistry from 1951 to 1953, when he joined the Max Planck Institute for Physical Chemistry in Göttingen, where he became director of the Department of Biochemical Kinetics in 1958. In that post he initiated the merger of the institutes for physical chemistry and spectroscopy to form the Max Planck Institute for Biophysical Chemistry in 1971. He served as its director until 1995.

Eigen was able to study many extremely fast chemical reactions by a variety of methods that he introduced and which are called relaxation techniques. These involve the application of bursts of energy to a solution that briefly destroy its equilibrium before a new equilibrium is reached. Eigen studied what happened to the solution in the extremely brief interval between the two equilibria by means of absorption spectroscopy. Among specific topics thus investigated were the rate of hydrogen ion formation through dissociation in water, diffusion-controlled protolytic reactions, and the kinetics of keto-enol tautomerism.

Details

Manfred Eigen (9 May 1927 – 6 February 2019) was a German biophysical chemist who won the 1967 Nobel Prize in Chemistry for work on measuring fast chemical reactions.

Eigen's research helped solve major problems in physical chemistry and aided in the understanding of chemical processes that occur in living organisms.

In later years, he explored the biochemical roots of life and evolution. He worked to install a multidisciplinary program at the Max Planck Institute to study the underpinnings of life at the molecular level. His work was hailed for creating a new scientific and technological discipline: evolutionary biotechnology.

Education and early life

Eigen was born on 9 May 1927 in Bochum, the son of Ernst and Hedwig (Feld) Eigen, a chamber musician. As a child he developed a deep passion for music, and studied piano.

World War II interrupted his formal education. At age fifteen he was drafted into service in a German antiaircraft unit. He was captured by the Americans toward the end of the war. He managed to escape (he said later that escape was relatively easy), and walked hundreds of miles across defeated Germany, arriving in Göttingen in 1945. He lacked the necessary documentation for acceptance to university, but was admitted after he demonstrated his knowledge in an exam. He entered the university's first postwar class.

Eigen desired to study physics, but since returning soldiers who were enrolled previously received priority, he enrolled in Geophysics. He earned an undergraduate degree and began graduate study in natural sciences. One of his advisors was Werner Heisenberg, the noted proponent of the uncertainty principle. He received his doctorate in 1951.

Career and research

Eigen received his Ph.D. at the University of Göttingen in 1951 under supervision of Arnold Eucken. In 1964 he presented the results of his research at a meeting of the Faraday Society in London. His findings demonstrated for the first time that it was possible to determine the rates of chemical reactions that occurred during time intervals as brief as a nanosecond.

Beginning in 1953 Eigen worked at the Max Planck Institute for Physical Chemistry in Göttingen, becoming its director in 1964 and joining it with the Max Planck Institute for Spectroscopy to become the Max Planck Institute for Biophysical Chemistry. He was an honorary professor of the Braunschweig University of Technology. From 1982 to 1993, Eigen was president of the German National Merit Foundation. Eigen was a member of the Board of Sponsors of The Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists.

In 1967, Eigen was awarded, along with Ronald George Wreyford Norrish and George Porter, the Nobel Prize in Chemistry. They were cited for their studies of extremely fast chemical reactions induced in response to very short pulses of energy.

In addition, Eigen's name is linked with the theory of quasispecies, the error threshold, error catastrophe, Eigen's paradox, and the chemical hypercycle, the cyclic linkage of reaction cycles as an explanation for the self-organization of prebiotic systems, which he described with Peter Schuster in 1977.

Eigen founded two biotechnology companies, Evotec and Direvo.

In 1981, Eigen became a founding member of the World Cultural Council.

Eigen was a member of the Pontifical Academy of Sciences even though he was an atheist. He died on 6 February 2019 at the age of 91.

Personal life

Eigen was married to Elfriede Müller. The union produced two children, a boy and a girl.[8] He later married Ruthild Winkler-Oswatitsch, a longtime scientific partner.

#220 Re: This is Cool » Miscellany » 2025-11-02 16:39:05

2434) Polyethylene terephthalate

Gist

Polyethylene terephthalate (PET or PETE) is a strong, lightweight, and clear thermoplastic polymer used for everything from food and beverage bottles to clothing fibers. It is made by combining ethylene glycol and terephthalic acid and is valued for its strength, barrier properties, and recyclability.

Polyethylene terephthalate which is also abbreviated as PET / PETE is mainly used to manufacture the packaging material for food products such as fruit and drinks containers. It is lightweight, transparent and also available in some colour.

Summary

Polyethylene terephthalate (or poly(ethylene terephthalate), PET, PETE, or the obsolete PETP or PET-P), is the most common thermoplastic polymer resin of the polyester family and is used in fibres for clothing, containers for liquids and foods, and thermoforming for manufacturing, and in combination with glass fibre for engineering resins.

In 2013, annual production of PET was 56 million tons. The biggest application is in fibres (in excess of 60%), with bottle production accounting for about 30% of global demand. In the context of textile applications, PET is referred to by its common name, polyester, whereas the acronym PET is generally used in relation to packaging. PET used in non-fiber applications (i.e. for packaging) makes up about 6% of world polymer production by mass. Accounting for the >60% fraction of polyethylene terephthalate produced for use as polyester fibers, PET is the fourth-most-produced polymer after polyethylene (PE), polypropylene (PP) and polyvinyl chloride (PVC).

PET consists of repeating (C10H8O4) units. PET is commonly recycled, and has the digit 1 as its resin identification code (RIC). The National Association for PET Container Resources (NAPCOR) defines PET as: "Polyethylene terephthalate items referenced are derived from terephthalic acid (or dimethyl terephthalate) and mono ethylene glycol, wherein the sum of terephthalic acid (or dimethyl terephthalate) and mono ethylene glycol reacted constitutes at least 90 percent of the mass of monomer reacted to form the polymer, and must exhibit a melting peak temperature between 225 °C and 255 °C, as identified during the second thermal scan in procedure 10.1 in ASTM D3418, when heating the sample at a rate of 10 °C/minute."

Depending on its processing and thermal history, polyethylene terephthalate may exist both as an amorphous (transparent) and as a semi-crystalline polymer. The semicrystalline material might appear transparent (particle size less than 500 nm) or opaque and white (particle size up to a few micrometers) depending on its crystal structure and particle size.

One process for making PET uses bis(2-hydroxyethyl) terephthalate, which can be synthesized by the esterification reaction between terephthalic acid and ethylene glycol with water as a byproduct (this is also known as a condensation reaction), or by transesterification reaction between ethylene glycol and dimethyl terephthalate (DMT) with methanol as a byproduct. It can also be obtained by recycling of PET itself.[10] Polymerization is through a polycondensation reaction of the monomers (done immediately after esterification/transesterification) with water as the byproduct.

Details

Polyethylene terephthalate (PET or PETE) is a strong, stiff synthetic fibre and resin and a member of the polyester family of polymers. PET is spun into fibres for permanent-press fabrics and blow-molded into disposable beverage bottles.

PET is produced by the polymerization of ethylene glycol and terephthalic acid. Ethylene glycol is a colourless liquid obtained from ethylene, and terephthalic acid is a crystalline solid obtained from xylene. When heated together under the influence of chemical catalysts, ethylene glycol and terephthalic acid produce PET in the form of a molten, viscous mass that can be spun directly to fibres or solidified for later processing as a plastic. In chemical terms, ethylene glycol is a diol, an alcohol with a molecular structure that contains two hydroxyl (OH) groups, and terephthalic acid is a dicarboxylic aromatic acid, an acid with a molecular structure that contains a large six-sided carbon (or aromatic) ring and two carboxyl (CO2H) groups. Under the influence of heat and catalysts, the hydroxyl and carboxyl groups react to form ester (CO-O) groups, which serve as the chemical links joining multiple PET units together into long-chain polymers. Water is also produced as a by-product.

The presence of a large aromatic ring in the PET repeating units gives the polymer notable stiffness and strength, especially when the polymer chains are aligned with one another in an orderly arrangement by drawing (stretching). In this semicrystalline form, PET is made into a high-strength textile fibre marketed under the trademarked name Dacron by the American company Invista. The stiffness of PET fibres makes them highly resistant to deformation, so they impart excellent resistance to wrinkling in fabrics. They are often used in durable-press blends with other fibres such as rayon, wool, and cotton, reinforcing the inherent properties of those fibres while contributing to the ability of the fabric to recover from wrinkling.

PET is also made into fibre filling for insulated clothing and for furniture and pillows. When made in very fine filaments, it is used in artificial silk, and in large-diameter filaments it is used in carpets. Among the industrial applications of PET are automobile tire yarns, conveyor belts and drive belts, reinforcement for fire hoses and garden hoses, seat belts (an application in which it has largely replaced nylon), nonwoven fabrics for stabilizing drainage ditches, culverts, and railroad beds, and nonwovens for use as diaper topsheets and disposable medical garments. PET is the most important of the synthetic fibres in weight produced and in value.

At a slightly higher molecular weight, PET is made into a high-strength plastic that can be shaped by all the common methods employed with other thermoplastics. PET films (often sold under the trademarks Mylar and Melinex) are produced by extrusion. Molten PET can be blow-molded into transparent containers of high strength and rigidity that are also virtually impermeable to gas and liquid. In this form, PET has become widely used in carbonated-beverage bottles and in jars for food processed at low temperatures. The low softening temperature of PET—approximately 70 °C (160 °F)—prevents it from being used as a container for hot foods.

PET is the most widely recycled plastic. In the United States, however, only about 20 percent of PET material is recycled. PET bottles and containers are commonly melted down and spun into fibres for fibrefill or carpets. When collected in a suitably pure state, PET can be recycled into its original uses, and methods have been devised for breaking the polymer down into its chemical precursors for resynthesizing into PET. The recycling code number for PET is 1.

PET was first prepared in England by J. Rex Whinfield and James T. Dickinson of the Calico Printers Association during a study of phthalic acid begun in 1940. Because of wartime restrictions, patent specifications for the new material were not immediately published. Production by Imperial Chemical of its Terylene-brand PET fibre did not begin until 1954. Meanwhile, by 1945 DuPont had independently developed a practical preparation process from terephthalic acid, and in 1953 the company began to produce Dacron fibre. PET soon became the most widely produced synthetic fibre in the world. In the 1970s, improved stretch-molding procedures were devised that allowed PET to be made into durable crystal-clear beverage bottles—an application that soon became second in importance only to fibre production.

Additional Information

Polyethylene terephthalate is one of the most common plastics. It’s used in a variety of items from water bottles and product packaging to baby wipes, clothing, bedding and mattresses. You’ll find polyethylene terephthalate written as PET or PETE, or the recycling code #1. On clothing and textile labels, you’ll find it listed as polyester.

The Problem

Making PET is an energy-intensive process. When used in the form of polyester for textiles, it uses far more energy than the manufacturing of other textiles like conventional or organic hemp and cotton, but it’s sold less expensively. In the production process, emissions can severely contaminate water sources with a number of pollutants.

PET does not readily break down in the environment. So, all of those wipes, water bottles, or product packs headed to the landfill will stick around – essentially – forever.

In addition to its issues with biodegradability, PET may pose some toxicity risks. Antimony trioxide is commonly used as a catalyst in the production process. Antimony trioxide is classified as possibly carcinogenic, and some forms are potentially endocrine disrupting.

Researchers have found antimony at detectable levels in polyester textiles. Even at low temperatures, antimony can migrate from polyester to saliva and sweat. One study concluded that exposure to antimony through polyester could result in potential health impacts for groups who wear polyester often and for prolonged period of times. Keep in mind that polyester is often used in active apparel and worn at times when the wearer is sweating.

This research also raises some unanswered questions about our exposure to antimony through polyester bedding while we sleep. Given that we spend about a third of our lives in bed, is it possible that this is prolonged and frequent enough exposure to experience associated health impacts from antimony? No research is available on this subject, so more study is needed.

A number of researchers have also confirmed that other estrogenic compounds are capable of migrating from PET water bottles into its contents.

PET and Plastic Pollution

Because PET doesn’t readily break down, it contributes to plastic pollution. Plastics like PET can break down into tiny pieces called microplastics, which are pervasive in our oceans – as well as our bays, lakes, and even drinking water. Plastics break down into tiny pieces, but they essentially never go away, as petroleum-derived plastic is typically not biodegradable.

Microplastics are often consumed by aquatic life, both large and small. And as the web of life goes, small aquatic animals that have eaten plastic are then consumed by predators. Those predators are consumed by even larger predators. The circle of life – predator becoming prey – allows microplastics to progressively build up with each successive level of the food chain. The largest predator of all? Humans.

Plastic particles have been found in seafood. What this means is that when we consume ocean animals, we may be unknowingly swallowing microplastics.

Unknown Impact

Researchers don’t yet understand how ingesting microplastics – whether from seafood or our drinking water – will impact humans. More study is needed to understand the risks. However, as mentioned above, researchers do know that plastics are capable of leaching toxic substances. Researchers also know that plastic can break down in animals’ stomachs. So it’s very possible that plastic can break down in our stomachs too and that it could be leaching harmful substances in the process.

The problem with plastic pollution isn’t just about humans. Building evidence suggests that marine animals may be threatened by consuming microplastics. And the plastic issue extends beyond consumption; animals can be entangled or smothered by debris, which can injure, debilitate, or even kill them. Some estimates say that if our use of plastic continues at this rate, there will be more plastic than fish in the ocean by 2050!

Finally, the overwhelming majority of plastic is not recycled. About 50 percent of plastic is used for single-use products – those designed to be used once (like a wipe, a to-go container, a water bottle, or a straw) and then thrown away. Less than 10 percent of plastic is actually recycled! That means that while recycling is indeed important, it’s even more important for each of us to refuse the use of single-use plastics.

#221 Dark Discussions at Cafe Infinity » Coat Quotes » 2025-11-02 15:52:23

- Jai Ganesh

- Replies: 0

Coat Quotes

1. I met in the street a very poor young man who was in love. His hat was old, his coat worn, his cloak was out at the elbows, the water passed through his shoes, - and the stars through his soul. - Victor Hugo

2. Whenever nature leaves a hole in a person's mind, she generally plasters it over with a thick coat of self-conceit. - Henry Wadsworth Longfellow

3. An aged man is but a paltry thing, a tattered coat upon a stick, unless soul clap its hands and sing, and louder sing for every tatter in its mortal dress. - William Butler Yeats

4. He that respects himself is safe from others. He wears a coat of mail that none can pierce. - Henry Wadsworth Longfellow

5. I thought I would dress in baggy pants, big shoes, a cane and a derby hat. everything a contradiction: the pants baggy, the coat tight, the hat small and the shoes large. - Charlie Chaplin

6. My dad used to say, 'Just because you dress up in a coat and tie, it doesn't influence your intelligence.' - Tiger Woods

7. Sometimes, wearing a scarf and a polo coat and no makeup and with a certain attitude of walking, I go shopping or just look at people living. But then, you know, there will be a few teenagers who are kind of sharp, and they'll say, 'Hey, just a minute. You know who I think that is?' And they'll start tailing me. And I don't mind. - Marilyn Monroe.

#222 Re: Jai Ganesh's Puzzles » General Quiz » 2025-11-02 15:24:23

Hi,

#10643. What does the term in Geography Chinook wind mean?

#10644. What does the term in Geography Chorography mean?

#223 Re: Jai Ganesh's Puzzles » English language puzzles » 2025-11-02 15:10:25

Hi,

#5839. What does the noun deniability mean?

#5840. What does the adjective desirous mean?

#224 Re: Jai Ganesh's Puzzles » Doc, Doc! » 2025-11-02 14:38:22

Hi,

#2514. Which part of the body is associated with Femoral nerve?

#225 Jokes » Beverage Jokes - I » 2025-11-02 14:30:35

- Jai Ganesh

- Replies: 0

Q:A man walked into a bar and drank ten cokes, then you know what happened?

A: He burped 7up.

* * *

Q: Why was the fly dancing on the top of the Pepsi bottle?

A: Because it said "Twist to open."

* * *

Q: Why did the man lose his job at the orange juice factory?

A: He couldn't concentrate!

* * *

Q: Why did the worker at the Pepsi bottling factory get fired?

A: He tested positive for Coke!

* * *

Q: Why did the orange stop rolling down the hill?

A: Because it ran out of juice!

* * *