Math Is Fun Forum

You are not logged in.

- Topics: Active | Unanswered

#1801 2025-10-13 17:55:37

- Jai Ganesh

- Administrator

- Registered: 2005-06-28

- Posts: 52,142

Re: crème de la crème

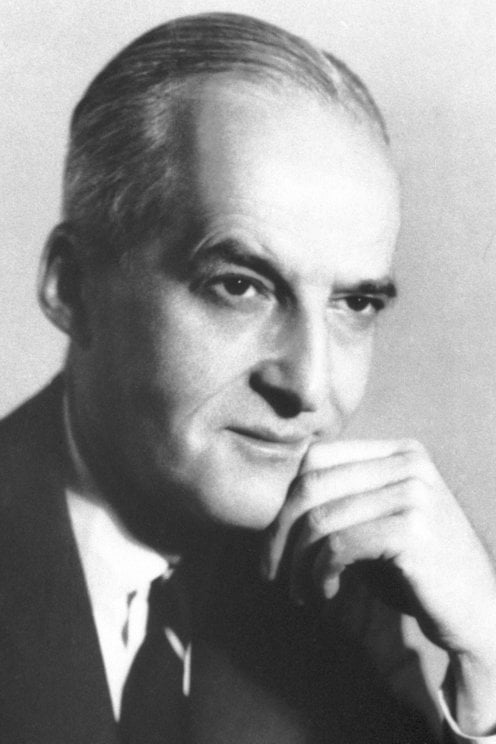

2364) Hannes Alfvén

Gist:

Work

The phenomenon of aurora borealis occurs when bursts of charged particles from the sun collide with the earth’s magnetic field. These jets of particles are an example of a special state of matter—plasma. Plasma is a gas comprised of electrons and ions (electrically charged atoms) that forms at high temperatures. From the late 1930s onward, Hannes Alfvén developed a theory about aurora borealis, which led to magneto-hydrodynamics; the theory of the relationships between a plasma’s movements, electric currents and fields, and magnetic fields.

Summary

Hannes Alfvén (born May 30, 1908, Norrköping, Sweden—died April 2, 1995, Djursholm) was an astrophysicist and winner, with Louis Néel of France, of the Nobel Prize for Physics in 1970 for his essential contributions in founding plasma physics—the study of plasmas (ionized gases).

Alfvén was educated at Uppsala University and in 1940 joined the staff of the Royal Institute of Technology, Stockholm. During the late 1930s and early ’40s he made remarkable contributions to space physics, including the theorem of frozen-in flux, according to which under certain conditions a plasma is bound to the magnetic lines of flux that pass through it. Alfvén later used the concept to explain the origin of cosmic rays.

In 1939 Alfvén published his theory of magnetic storms and auroral displays in the atmosphere, which immensely influenced the modern theory of the magnetosphere (the region of Earth’s magnetic field). He discovered a widely used mathematical approximation by which the complex spiral motion of a charged particle in a magnetic field can be easily calculated. Magnetohydrodynamics (MHD), the study of plasmas in magnetic fields, was largely pioneered by Alfvén, and his work has been acknowledged as fundamental to attempts to control nuclear fusion.

After numerous disagreements with the Swedish government, Alfvén obtained a position (1967) with the University of California, San Diego. Later he divided his teaching time between the Royal Institute of Technology in Stockholm and the University of California.

Alfvén devised “plasma cosmology,” a concept that challenged the big-bang model of the origin of the universe. The theory posited that the universe had no beginning (and has no foreseeable end) and that plasma—with its electric and magnetic forces—has done more to organize matter in the universe into star systems and other large observed structures than has the force of gravity. Much of Alfvén’s early research was included in his Cosmical Electrodynamics (1950). He also wrote On the Origin of the Solar System (1954), Worlds-Antiworlds (1966), and Cosmic Plasma (1981).

Details

Hannes Olof Gösta Alfvén (30 May 1908 – 2 April 1995) was a Swedish electrical engineer, plasma physicist and winner of the 1970 Nobel Prize in Physics for his work on magnetohydrodynamics (MHD). He described the class of MHD waves now known as Alfvén waves. He was originally trained as an electrical power engineer and later moved to research and teaching in the fields of plasma physics and electrical engineering. Alfvén made many contributions to plasma physics, including theories describing the behavior of aurorae, the Van Allen radiation belts, the effect of magnetic storms on the Earth's magnetic field, the terrestrial magnetosphere, and the dynamics of plasmas in the Milky Way galaxy.

Education

Alfvén received his PhD from the University of Uppsala in 1934. His thesis was titled "Investigations of High-frequency Electromagnetic Waves."

Early years

In 1934, Alfvén taught physics at both the University of Uppsala and the Nobel Institute for Physics (later renamed the Manne Siegbahn Institute of Physics) in Stockholm, Sweden. In 1940, he became professor of electromagnetic theory and electrical measurements at the Royal Institute of Technology in Stockholm. In 1945, he acquired the nonappointive position of Chair of Electronics. His title was changed to Chair of Plasma Physics in 1963. From 1954 to 1955, Alfvén was a Fulbright Scholar at the University of Maryland, College Park. In 1967, after leaving Sweden and spending time in the Soviet Union, he moved to the United States. Alfvén worked in the departments of electrical engineering at both the University of California, San Diego and the University of Southern California.

Later years

In 1991, Alfvén retired as professor of electrical engineering at the University of California, San Diego and professor of plasma physics at the Royal Institute of Technology in Stockholm.

Alfvén spent his later adult life alternating between California and Sweden. He died at the age of 86.

Personal life

Alfvén was married for 67 years to his wife Kerstin (1910–1992). They raised five children, one boy and four girls. Their son became a physician, while one daughter became a writer and another a lawyer in Sweden. The writer was Inger Alfvén and is well known for her work in Sweden. The composer Hugo Alfvén was Hannes Alfvén's uncle.

Alfvén studied the history of science, oriental philosophy, and religion. On his religious views, Alfven was irreligious and critical of religion. He spoke Swedish, English, German, French, and Russian, and some Spanish and Chinese. He expressed great concern about the difficulties of permanent high-level radioactive waste management." Alfvén was also interested in problems in cosmology and all aspects of auroral physics, and used Schröder's well known book on aurora, Das Phänomen des Polarlichts. Letters of Alfvén, Treder, and Schröder were published on the occasion of Treder's 70th birthday. The relationships between Hans-Jürgen Treder, Hannes Alfvén and Wilfried Schröder were discussed in detail by Schröder in his publications.

Alfvén died on 2 April, 1995 at Djursholm aged 86.

It appears to me that if one wants to make progress in mathematics, one should study the masters and not the pupils. - Niels Henrik Abel.

Nothing is better than reading and gaining more and more knowledge - Stephen William Hawking.

Offline

#1802 2025-10-15 18:13:16

- Jai Ganesh

- Administrator

- Registered: 2005-06-28

- Posts: 52,142

Re: crème de la crème

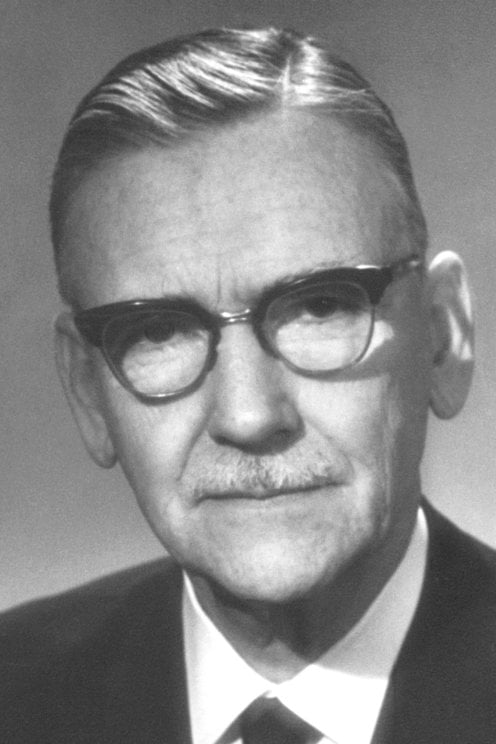

2365) Louis Néel

Gist:

Work

Magnetism takes different forms, some stemming from the magnetic moments of atoms of different materials. In ferromagnetic material the magnetic moments are oriented in the same direction. In 1932 Louis Néel described the antiferromagnetism phenomenon, where nearby magnetic moments in a material are oriented in opposite directions. In 1947 he also described the ferrimagnetism phenomenon, where the magnetic moments are aligned in opposite directions but of different magnitudes. The findings became an important factor in the development of computer memory and other applications.

Summary

Louis-Eugène-Félix Néel (born November 22, 1904, Lyon, France—died November 17, 2000, Brive-Corrèze) was a French physicist who was corecipient, with the Swedish astrophysicist Hannes Alfvén, of the Nobel Prize for Physics in 1970 for his pioneering studies of the magnetic properties of solids. His contributions to solid-state physics have found numerous useful applications, particularly in the development of improved computer memory units.

Néel attended the École Normale Supérieure in Paris and the University of Strasbourg (Ph.D., 1932), where he studied under Pierre-Ernest Weiss and first began researching magnetism. He was a professor at the universities of Strasbourg (1937–45) and Grenoble (1945–76), and in 1956 he founded the Center for Nuclear Studies in Grenoble, serving as its director until 1971. Néel also was director (1971–76) of the Polytechnic Institute in Grenoble.

During the early 1930s Néel studied, on the molecular level, forms of magnetism that differ from ferromagnetism. In ferromagnetism, the most common variety of magnetism, the electrons line up (or spin) in the same direction at low temperatures. He discovered that, in some substances, alternating groups of atoms align their electrons in opposite directions (much as when two identical magnets are placed together with opposite poles aligned), thus neutralizing the net magnetic effect. This magnetic property is called antiferromagnetism. Néel’s studies of fine-grain ferromagnetics provided an explanation for the unusual magnetic memory of certain mineral deposits that has provided information on changes in the direction and strength of the Earth’s magnetic field.

Néel wrote more than 200 works on various aspects of magnetism. Mainly because of his contributions, ferromagnetic materials can be manufactured to almost any specifications for technical applications, and a flood of new synthetic ferrite materials has revolutionized microwave electronics.

Details

Louis Eugène Félix Néel (22 November 1904 – 17 November 2000) was a French physicist born in Lyon who received the Nobel Prize for Physics in 1970 for his studies of the magnetic properties of solids.

Biography

Néel studied at the Lycée du Parc in Lyon and was accepted at the École Normale Supérieure in Paris. He obtained the degree of Doctor of Science at the University of Strasbourg. He was corecipient (with the Swedish astrophysicist Hannes Alfvén) of the Nobel Prize for Physics in 1970 for his pioneering studies of the magnetic properties of solids. His contributions to solid state physics have found numerous useful applications, particularly in the development of improved computer memory units. About 1930 he suggested that a new form of magnetic behavior might exist; called antiferromagnetism, as opposed to ferromagnetism. Above a certain temperature (the Néel temperature) this behaviour stops. Néel pointed out (1948) that materials could also exist showing ferrimagnetism. Néel has also given an explanation of the weak magnetism of certain rocks, making possible the study of the history of Earth's magnetic field.

He is the instigator of the Polygone Scientifique in Grenoble.

The Louis Néel Medal, awarded annually by the European Geophysical Society, is named in Néel's honour.

Néel died at Brive-la-Gaillarde on 17 November 2000 at the age 95, just 5 days short of his 96th birthday.

It appears to me that if one wants to make progress in mathematics, one should study the masters and not the pupils. - Niels Henrik Abel.

Nothing is better than reading and gaining more and more knowledge - Stephen William Hawking.

Offline

#1803 2025-10-16 17:29:43

- Jai Ganesh

- Administrator

- Registered: 2005-06-28

- Posts: 52,142

Re: crème de la crème

2366) Luis Federico Leloir

Gist:

Work

Carbohydrates, including sugars and starches, are of paramount importance to the life processes of organisms. Luis Leloir demonstrated that nucleotides—molecules that also constitute the building blocks of DNA molecules—are crucial when carbohydrates are generated and converted. In 1949 Leloir discovered that one type of sugar’s conversion to another depends on a molecule that consists of a nucleotide and a type of sugar. He later showed that the generation of carbohydrates is not an inversion of metabolism, as had been assumed previously, but processes with other steps.

Summary

Luis Federico Leloir (born Sept. 6, 1906, Paris, France—died Dec. 2, 1987, Buenos Aires, Arg.) was an Argentine biochemist who won the Nobel Prize for Chemistry in 1970 for his investigations of the processes by which carbohydrates are converted into energy in the body.

After serving as an assistant at the Institute of Physiology, University of Buenos Aires, from 1934 to 1935, Leloir worked a year at the biochemical laboratory at the University of Cambridge and in 1937 returned to the Institute of Physiology, where he undertook investigations of the oxidation of fatty acids. In 1947 he obtained financial support to set up the Institute for Biochemical Research, Buenos Aires, where he began research on the formation and breakdown of lactose, or milk sugar, in the body. That work ultimately led to his discovery of sugar nucleotides, which are key elements in the processes by which sugars stored in the body are converted into energy. He also investigated the formation and utilization of glycogen and discovered certain liver enzymes that are involved in its synthesis from glucose.

Details

Luis Federico Leloir (September 6, 1906 – December 2, 1987) was an Argentine physician and biochemist who received the 1970 Nobel Prize in Chemistry for his discovery of the metabolic pathways by which carbohydrates are synthesized and converted into energy in the body. Although born in France, Leloir received the majority of his education at the University of Buenos Aires and was director of the private research group Fundación Instituto Campomar until his death in 1987. His research into sugar nucleotides, carbohydrate metabolism, and renal hypertension garnered international attention and led to significant progress in understanding, diagnosing and treating the congenital disease galactosemia. Leloir is buried in La Recoleta Cemetery, Buenos Aires.

Biography:

Early years

Leloir's parents, Federico Augusto Rufino and Hortencia Aguirre de Leloir, traveled from Buenos Aires to Paris in the middle of 1906 with the intention of treating Federico's illness. However, Federico died in late August, and a week later Luis was born in an old house at 81 Víctor Hugo Road in Paris, a few blocks away from the Arc de Triomphe. After returning to Argentina in 1908, Leloir lived together with his eight siblings on their family's extensive property El Tuyú that his grandparents had purchased after their immigration from the Basque Country of northern Spain: El Tuyú comprises 400 {km}^{2} of sandy land along the coastline from San Clemente del Tuyú to Mar de Ajó which has since become a popular tourist attraction.

During his childhood, the future Nobel Prize winner found himself observing natural phenomena with particular interest; his schoolwork and readings highlighted the connections between the natural sciences and biology. His education was divided between Escuela General San Martín (primary school), Colegio Lacordaire (secondary school), and for a few months at Beaumont College in England. His grades were unspectacular, and his first stint in college ended quickly when he abandoned his architectural studies that he had begun in Paris' École Polytechnique.

It was during the 1920s that Leloir invented salsa golf (golf sauce). After being served prawns with the usual sauce during lunch with a group of friends at the Ocean Club in Mar del Plata, Leloir came up with a peculiar combination of ketchup and mayonnaise to spice up his meal. With the financial difficulties that later plagued Leloir's laboratories and research, he would joke, "If I had patented that sauce, we'd have a lot more money for research right now.

Nobel Prize

On December 2, 1970, Leloir received the Nobel Prize for Chemistry from the King of Sweden for his discovery of the metabolic pathways in lactose, becoming only the third Argentine to receive the prestigious honor in any field at the time. In his acceptance speech at Stockholm, he borrowed from Winston Churchill's famous 1940 speech to the House of Commons and remarked, "never have I received so much for so little". Leloir and his team reportedly celebrated by drinking champagne from test tubes, a rare departure from the humility and frugality that characterized the atmosphere of Fundación Instituto Campomar under Leloir's direction. The $80,000 prize money was spent directly on research, and when asked about the significance of his achievement, Leloir responded:

"This is only one step in a much larger project. I discovered (no, not me: my team) the function of sugar nucleotides in cell metabolism. I want others to understand this, but it is not easy to explain: this is not a very noteworthy deed, and we hardly know even a little."

It appears to me that if one wants to make progress in mathematics, one should study the masters and not the pupils. - Niels Henrik Abel.

Nothing is better than reading and gaining more and more knowledge - Stephen William Hawking.

Offline

#1804 Yesterday 23:10:37

- Jai Ganesh

- Administrator

- Registered: 2005-06-28

- Posts: 52,142

Re: crème de la crème

2367) Julius Axelrod

Gist:

Work

The nervous systems of people and animals consist of many nerve cells with long extensions, or nerve fibers. Signals are conveyed between cells by small electrical currents and by special substances known as signal substances. The transfers occur via contacts, or synapses. Julius Axelrod studied noradrenaline, a signal substance that provides signals to increase activity in the case of aggression or danger. Among other things, in 1957 he showed how an excess of noradrenaline is released in response to nerve impulses and then returns to the place were it is stored after the signal is implemented.

Summary

Julius Axelrod (born May 30, 1912, New York, New York, U.S.—died December 29, 2004, Rockville, Maryland) was an American biochemist and pharmacologist who, along with the British biophysicist Sir Bernard Katz and the Swedish physiologist Ulf von Euler, was awarded the Nobel Prize for Physiology or Medicine in 1970. Axelrod’s contribution was his identification of an enzyme that degrades chemical neurotransmitters within the nervous system after they are no longer needed to transmit nerve impulses.

A graduate of the College of the City of New York (B.S., 1933), New York University (M.S., 1941), and George Washington University (Ph.D., 1955), Axelrod worked as a chemist in the Laboratory of Industrial Hygiene at New York City’s Health Department (1935–46) and then joined the research division of Goldwater Memorial Hospital (1946), where his studies on analgesic medications helped identify acetaminophen as the chemical responsible for relieving pain. Marketed under such trade names as Tylenol and Panadol, acetaminophen became one of the most widely used painkillers in the world. In 1949 Axelrod left the hospital to join the staff of the section on chemical pharmacology at the National Heart Institute in Bethesda, Maryland. In 1955 he moved to the staff of the National Institute of Mental Health, where he became chief of the pharmacology section of the Laboratory of Clinical Sciences. He remained at the institute until his retirement in 1984.

Axelrod’s Nobel Prize-winning research grew out of work done by Euler, specifically Euler’s discovery of noradrenaline (norepinephrine), a chemical substance that transmits nerve impulses. Axelrod, in turn, discovered that noradrenaline could be neutralized by an enzyme, catechol-O-methyltransferase, which he isolated and named. This enzyme proved critical to an understanding of the entire nervous system. The enzyme was shown to be useful in dealing with the effects of certain psychotropic drugs and in research on hypertension and schizophrenia.

Details

Julius Axelrod (May 30, 1912 – December 29, 2004) was an American biochemist. He won a share of the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1970 along with Bernard Katz and Ulf von Euler. The Nobel Committee honored him for his work on the release and reuptake of catecholamine neurotransmitters, a class of chemicals in the brain that include epinephrine, norepinephrine, and, as was later discovered, dopamine. Axelrod also made major contributions to the understanding of the pineal gland and how it is regulated during the sleep-wake cycle.

Education and early life

Axelrod was born in New York City, the son of Jewish immigrants from Poland, Molly (née Leichtling) and Isadore Axelrod, a basket weaver.[9] He received his bachelor's degree in biology from the College of the City of New York in 1933. Axelrod wanted to become a physician, but was rejected from every medical school to which he applied. He worked briefly as a laboratory technician at New York University, then in 1935 he got a job with the New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene testing vitamin supplements added to food. While working at the Department of Health, he attended night school and received his master's in sciences degree from New York University in 1941.

Research:

Analgesic research

In 1946, Axelrod took a position working under Bernard Brodie at Goldwater Memorial Hospital. The research experience and mentorship Axelrod received from Brodie would launch him on his research career. Brodie and Axelrod's research focused on how analgesics (pain-killers) work. During the 1940s, users of non-aspirin analgesics were developing a blood condition known as methemoglobinemia. Axelrod and Brodie discovered that acetanilide, the main ingredient of these pain-killers, was to blame. They found that one of the metabolites also was an analgesic. They recommended that this metabolite, acetaminophen (paracetamol, Tylenol), be used instead.

Catecholamine research

In 1949, Axelrod began work at the National Heart Institute, forerunner of the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI), part of the National Institutes of Health (NIH). He examined the mechanisms and effects of caffeine, which led him to an interest in the sympathetic nervous system and its main neurotransmitters, epinephrine and norepinephrine. During this time, Axelrod also conducted research on codeine, morphine, methamphetamine, and ephedrine and performed some of the first experiments on LSD. Realizing that he could not advance his career without a PhD, he took a leave of absence from the NIH in 1954 to attend George Washington University Medical School. Allowed to submit some of his previous research toward his degree, he graduated one year later, in 1955. Axelrod then returned to the NIH and began some of the key research of his career.

Axelrod received his Nobel Prize for his work on the release, reuptake, and storage of the neurotransmitters epinephrine and norepinephrine, also known as adrenaline and noradrenaline. Working on monoamine oxidase (MAO) inhibitors in 1957, Axelrod showed that catecholamine neurotransmitters do not merely stop working after they are released into the synapse. Instead, neurotransmitters are recaptured ("reuptake") by the pre-synaptic nerve ending, and recycled for later transmissions. He theorized that epinephrine is held in tissues in an inactive form and is liberated by the nervous system when needed. This research laid the groundwork for later selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), such as Prozac, which block the reuptake of another neurotransmitter, serotonin.

In 1958, Axelrod also discovered and characterized the enzyme catechol-O-methyl transferase, which is involved in the breakdown of catecholamines.

Pineal gland research

Some of Axelrod's later research focused on the pineal gland. He and his colleagues showed that the hormone melatonin is generated from tryptophan, as is the neurotransmitter serotonin. The rates of synthesis and release follows the body's circadian rhythm driven by the suprachiasmatic nucleus within the hypothalamus. Axelrod and colleagues went on to show that melatonin had wide-ranging effects throughout the central nervous system, allowing the pineal gland to function as a biological clock. He was elected a Fellow of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences in 1971. He continued to work at the National Institute of Mental Health at the NIH until his death in 2004.

Many of his papers and awards are held at the National Library of Medicine.

Awards and honors

Axelrod was awarded the Gairdner Foundation International Award in 1967 and the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1970. He was elected a Foreign Member of the Royal Society in 1979 In 1992, he was awarded the Ralph W. Gerard Prize in Neuroscience. He was elected to the American Philosophical Society in 1995.

Research trainees

Solomon Snyder, Irwin Kopin, Ronald W. Holz, Rudi Schmid, Bruce R. Conklin, Ron M. Burch, Juan M. Saavedra, Marty Zatz, Richard M. Weinshilboum, Michael Brownstein, Chris Felder, Lewis Landsberg, Robert Kanterman, Richard J. Wurtman.

Personal life

Axelrod injured his left eye when an ammonia bottle in the lab exploded; he would wear an eyepatch for the rest of his life. Although he became an atheist early in life and resented the strict upbringing of his parents' religion, he identified with Jewish culture and joined several international fights against anti-Semitism. His wife of 53 years, Sally Taub Axelrod, died in 1992. At his death, on December 29, 2004, he was survived by two sons, Paul and Alfred, and three grandchildren.

Political views

After receiving the Nobel Prize in 1970, Axelrod used his visibility to advocate several science policy issues. In 1973 U.S. President Richard Nixon created an agency with the specific goal of curing cancer. Axelrod, along with fellow Nobel-laureates Marshall W. Nirenberg and Christian Anfinsen, organized a petition by scientists opposed to the new agency, arguing that by focusing solely on cancer, public funding would not be available for research into other, more solvable, medical problems. Axelrod also lent his name to several protests against the imprisonment of scientists in the Soviet Union. Axelrod was a member of the Board of Sponsors of the Federation of American Scientists and the International Academy of Science, Munich.

It appears to me that if one wants to make progress in mathematics, one should study the masters and not the pupils. - Niels Henrik Abel.

Nothing is better than reading and gaining more and more knowledge - Stephen William Hawking.

Offline

#1805 Today 17:02:23

- Jai Ganesh

- Administrator

- Registered: 2005-06-28

- Posts: 52,142

Re: crème de la crème

2368) Ulf von Euler

Gist:

Work

Human and animal nervous systems consist of a large variety of cells with long nerve fibers. Small electrical currents and special chemical substances (neurotransmitters) are passed between cells through contacts (synapses). In 1947 Ulf von Euler discovered the neurotransmitter norepinephrine, which plays an important role in producing fight-or-flight signals. He subsequently showed that norepinephrine is formed and stored in packages, or vesicles, sent between neurons via synapses.

Summary

Ulf von Euler (born Feb. 7, 1905, Stockholm, Sweden—died March 9, 1983, Stockholm) was a Swedish physiologist who, with British biophysicist Sir Bernard Katz and American biochemist Julius Axelrod, received the 1970 Nobel Prize for Physiology or Medicine. All three were honoured for their independent study of the mechanics of nerve impulses.

Euler was the son of 1929 Nobel laureate Hans von Euler-Chelpin. After his graduation from the Karolinska Institute in Stockholm, Euler served on the faculty of the institute from 1930 to 1971. He joined the Nobel Committee for Physiology and Medicine in 1953 and was president of the Nobel Foundation for 10 years (1966–75).

Euler’s outstanding achievement was his identification of noradrenaline (norepinephrine), the key neurotransmitter (or impulse carrier) in the sympathetic nervous system. He also found that norepinephrine is stored within nerve fibres themselves. These discoveries laid the foundation for Axelrod’s determination of the role of the enzyme that inhibits its action, and the method of norepinephrine’s reabsorption by nerve tissues. Euler also discovered the hormones known as prostaglandins, which play active roles in stimulating human muscle contraction and in the regulation of the cardiovascular and nervous systems.

Details

Ulf Svante von Euler (7 February 1905 – 9 March 1983) was a Swedish physiologist and pharmacologist. He shared the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1970 for his work on neurotransmitters.

Life

Ulf Svante von Euler-Chelpin was born in Stockholm, the son of two noted scientists, Hans von Euler-Chelpin, a professor of chemistry, and Astrid Cleve, a professor of botany and geology. His father was German and the recipient of Nobel Prize for Chemistry in 1929, and his maternal grandfather was Per Teodor Cleve, Professor of Chemistry at the Uppsala University, and the discoverer of the chemical elements thulium and holmium. Von Euler-Chelpin studied medicine at the Karolinska Institute in 1922. At Karolinska, he worked under Robin Fåhraeus in blood sedimentation and rheology and did research work on the pathophysiology of vasoconstriction. He presented his doctoral thesis in 1930, and was appointed as assistant professor in pharmacology in the same year, with the support of G. Liljestrand. From 1930 to 1931, von Euler-Chelpin got a Rochester Fellowship to do his post-doctoral studies abroad. He studied in England with Sir Henry Dale in London and with I. de Burgh Daly in Birmingham, and then proceeded to the continent, studying with Corneille Heymans in Ghent, Belgium and with Gustav Embden in Frankfurt, Germany. Von Euler liked to travel, so he also worked and learned biophysics with Archibald Vivian Hill, again in London in 1934, and neuromuscular transmission with G. L. Brown in 1938. From 1946 to 1947, he worked with Eduardo Braun-Menéndez in the Instituto de Biología y Medicina Experimental in Buenos Aires, which was founded by Bernardo Houssay. His unerring instinct to work with important scientific leaders and fields was to be proved by the fact that Dale, Heymans, Hill and Houssay went to receive the Nobel prize in physiology or medicine.

In 1981, von Euler became a founding member of the World Cultural Council.

From 1930 to 1957, von Euler was married to Jane Anna Margarethe Sodenstierna (1905–2004). They had four children: Hans Leo, scientist administrator at the National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, Maryland, U.S.A.; Johan Christopher, anesthesiologist, Serafimer Hospital, Stockholm; Ursula Katarina, Ph.D., curator at The Royal Collections, The Royal Court, Stockholm, Sweden; and Marie Jane, Chemical Engineer, Melbourne, Australia. In 1958, von Euler married countess Dagmar Cronstedt, a radio broadcaster who had during the Second World War worked at Radio Königsberg, broadcasting German propaganda to neutral Sweden.

Research

His short stay as a postdoctoral student in Dale's laboratory was very fruitful: in 1931 he discovered with John H. Gaddum an important autopharmacological principle, substance P. After returning to Stockholm, von Euler pursued further this line of research, and successively discovered four other important endogenous active substances, prostaglandin, vesiglandin (1935), piperidine (1942) and noradrenaline (1946).

In 1939 von Euler was appointed full professor of physiology at the Karolinska Institute, where he remained until 1971. His early collaboration with Liljestrand had led to an important discovery, which was named the Euler–Liljestrand mechanism (a physiological arterial shunt in response to the decrease in local oxygenation of the lungs).

From 1946 on, however, when noradrenaline (abbreviated NA or NAd) was discovered, von Euler devoted most of his research work to this area. He and his group studied thoroughly its distribution and fate in biological tissues and in the nervous system in physiological and pathological conditions, and found that noradrenaline was produced and stored in nerve synaptic terminals in intracellular vesicles, a key discovery which changed dramatically the course of many researches in the field. In 1970 he was distinguished with the Nobel Prize for his work, jointly with Sir Bernard Katz and Julius Axelrod. Since 1953 he was very active in the Nobel Foundation, being a member of the Nobel Committee for Physiology or Medicine and chairman of the board since 1965. He also served as vice-president of the International Union of Physiological Sciences from 1965 to 1971. Among the many honorary titles and prizes he received in addition to the Nobel, were the Gairdner Prize (1961), the Jahre Prize (1965), the Stouffer Prize (1967), the Carl Ludwig Medaille (1953), the Schmiedeberg Plaquette (1969), La Madonnina (1970), many honorary doctorates from universities around the world, and the membership to several erudite, medical and scientific societies. He was elected a member of the American Philosophical Society in 1970, a member of both the American Academy of Arts and Sciences and the United States National Academy of Sciences in 1972, and a Foreign Member of the Royal Society (ForMemRS) in 1973.

It appears to me that if one wants to make progress in mathematics, one should study the masters and not the pupils. - Niels Henrik Abel.

Nothing is better than reading and gaining more and more knowledge - Stephen William Hawking.

Offline