Math Is Fun Forum

You are not logged in.

- Topics: Active | Unanswered

#1 Re: Dark Discussions at Cafe Infinity » crème de la crème » Today 18:00:01

2439) Cyril N. Hinshelwood

Gist:

Work

During chemical reactions, atoms and molecules regroup and form new constellations. When molecules formed during a reaction readily react with molecules present from the beginning, a chain reaction can occur. Explosions and fire are examples of chain reactions. During the 1930s Cyril Hinshelwood analyzed conditions and sequences of events involved in chain reactions from a theoretical standpoint. Among other things, he found that the theoretical results corresponded with observations of the reaction between hydrogen and oxygen.

Summary

Sir Cyril Norman Hinshelwood (born June 19, 1897, London, Eng.—died Oct. 9, 1967, London) was a British chemist who worked on reaction rates and reaction mechanisms, particularly that of the combination of hydrogen and oxygen to form water, one of the most fundamental combining reactions in chemistry. For this work he shared the 1956 Nobel Prize for Chemistry with the Soviet scientist Nikolay Semyonov.

Hinshelwood obtained his doctorate at the University of Oxford in 1924 and became professor of chemistry there in 1937. After retiring from Oxford in 1964 he became a senior research fellow at Imperial College, London.

About 1930 Hinshelwood began investigating the complex reaction in which hydrogen and oxygen atoms combine to form water. He showed that the products of this reaction help to spread the reaction further in what is essentially a chain reaction.

He next sought to explore molecular kinetics within the bacterial cell. Upon observing the biological responses of bacteria to changes in environment, he concluded that more or less permanent changes in a cell’s resistance to a drug could be induced. This finding was important in regard to bacterial resistance to antibiotic and other chemotherapeutic agents. Hinshelwood was knighted in 1948. His publications include The Kinetics of Chemical Change in Gaseous Systems (1926) and The Chemical Kinetics of the Bacterial Cell (1946).

Details

Sir Cyril Norman Hinshelwood (19 June 1897 – 9 October 1967) was a British physical chemist and expert in chemical kinetics. His work in reaction mechanisms earned the 1956 Nobel Prize in chemistry.

Education

Born in London, his parents were Norman Macmillan Hinshelwood, a chartered accountant, and Ethel Frances née Smith. He was educated first in Canada, returning in 1905 on the death of his father to a small flat in Chelsea where he lived for the rest of his life. He then studied at Westminster City School and Balliol College, Oxford.

Career

During the First World War, Hinshelwood was a chemist in an explosives factory. He was a tutor at Trinity College, Oxford, from 1921 to 1937 and was Dr Lee's Professor of Chemistry at the University of Oxford from 1937. He served on several advisory councils on scientific matters to the British Government.

His early studies of molecular kinetics led to the publication of Thermodynamics for Students of Chemistry and The Kinetics of Chemical Change in 1926. With Harold Warris Thompson he studied the explosive reaction of hydrogen and oxygen and described the phenomenon of chain reaction. His subsequent work on chemical changes in the bacterial cell proved to be of great importance in later research work on antibiotics and therapeutic agents, and his book, The Chemical Kinetics of the Bacterial Cell was published in 1946, followed by Growth, Function and Regulation in Bacterial Cells in 1966. In 1951 he published The Structure of Physical Chemistry. It was republished as an Oxford Classic Texts in the Physical Sciences by Oxford University Press in 2005.

The Langmuir-Hinshelwood process in heterogeneous catalysis, in which the adsorption of the reactants on the surface is the rate-limiting step, is named after him. He was a senior research fellow at Imperial College London from 1964 to 1967.

Awards and honours

In addition to being named the second Dr. Lee's Professor of Chemistry at Oxford, Hinshelwood was elected Fellow of the Royal Society (FRS) in 1929, serving as president from 1955 to 1960. He was knighted in 1948 and appointed to the Order of Merit in 1960. With Nikolay Semenov of the USSR, Hinshelwood was jointly awarded the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 1956 for his researches into the mechanism of chemical reactions. He was also an elected member of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, the United States National Academy of Sciences, and the American Philosophical Society.

Hinshelwood was president of the Chemical Society, the Royal Society, the Classical Association, and the Faraday Society, and received numerous awards and honorary degrees. He was elected on 1 January 1960 to honorary membership of the Manchester Literary and Philosophical Society who awarded him its Dalton medal in 1966.

Personal life

Hinshelwood never married. He was fluent in seven classical and modern languages and his main hobbies were painting, collecting Chinese pottery, and foreign literature. As an artist, Hinshelwood painted scenes in Oxford, as well as portraits of Oxford University people including Harold Hartley, his doctoral supervisor, and Herbert Blakiston, the President of Trinity College. The portrait of Hartley is now owned by the Royal Society, and that of Blakiston is owned by Trinity College, as are a number of Hinshelwood's other paintings.

He died, at home, on 9 October 1967. In 1968, his Nobel Prize medal was sold by his estate to a collector, who then sold it in 1976 for $15,000. In 2017, his Nobel Prize medal was sold at auction for $128,000.

#2 Re: This is Cool » Miscellany » Today 17:31:14

2502) Maglev Train

Gist

Maglev (magnetic levitation) trains are high-speed vehicles that use electromagnetic forces to float, guide, and propel themselves 10 cm (approx. 4 inches) above a guideway instead of using wheels, axles, or traditional engines. By eliminating friction, they achieve speeds exceeding 600 km/h (373 mph), offering a quiet, low-maintenance, and energy-efficient alternative to traditional rail.

Maglev trains are significantly faster than traditional bullet trains because they use magnetic levitation to float above the tracks, eliminating friction and allowing for much higher speeds, with operational speeds over 500 km/h compared to bullet trains' 320 km/h, and test records exceeding 600 km/h.

Summary

Maglev is a a floating vehicle for land transportation that is supported by either electromagnetic attraction or repulsion. Maglevs were conceptualized during the early 1900s by American professor and inventor Robert Goddard and French-born American engineer Emile Bachelet and have been in commercial use since 1984, with several operating at present and extensive networks proposed for the future.

Maglevs incorporate a basic fact about magnetic forces—like magnetic poles repel each other, and opposite magnetic poles attract each other—to lift, propel, and guide a vehicle over a track (or guideway). Maglev propulsion and levitation may involve the use of superconducting materials, electromagnets, diamagnets, and rare-earth magnets.

Electromagnetic suspension (EMS) and electrodynamic suspension (EDS)

Two types of maglevs are in service. Electromagnetic suspension (EMS) uses the attractive force between magnets present on the train’s sides and underside and on the guideway to levitate the train. A variation on EMS, called Transrapid, employs an electromagnet to lift the train off the guideway. The attraction from magnets present on the underside of the vehicle that wrap around the iron rails of the guideway keep the train about 1.3 cm (0.5 inch) above the guideway.

Electrodynamic suspension (EDS) systems are similar to EMS in several respects, but the magnets are used to repel the train from the guideway rather than attract them. These magnets are supercooled and superconducting and have the ability to conduct electricity for a short time after power has been cut. (In EMS systems a loss of power shuts down the electromagnets.) Also, unlike EMS, the charge of the magnetized coils of the guideway in EDS systems repels the charge of magnets on the undercarriage of the train so that it levitates higher (typically in the range of 1–10 cm [0.4–3.9 inches]) above the guideway. EDS trains are slow to lift off, so they have wheels that must be deployed below approximately 100 km (62 miles) per hour. Once levitated, however, the train is moved forward by propulsion provided by the guideway coils, which are constantly changing polarity owing to alternating electrical current that powers the system.

Maglevs eliminate a key source of friction—that of train wheels on the rails—although they must still overcome air resistance. This lack of friction means that they can reach higher speeds than conventional trains. At present maglev technology has produced trains that can travel in excess of 500 km (310 miles) per hour. This speed is twice as fast as a conventional commuter train and comparable to the TGV (Train à Grande Vitesse) in use in France, which travels between 300 and 320 km (186 and 199 miles) per hour. Because of air resistance, however, maglevs are only slightly more energy efficient than conventional trains.

Benefits and costs

Maglevs have several other advantages compared with conventional trains. They are less expensive to operate and maintain, because the absence of rolling friction means that parts do not wear out quickly (as do, for instance, the wheels on a conventional railcar). This means that fewer materials are consumed by the train’s operation, because parts do not constantly have to be replaced. The design of the maglev cars and railway makes derailment highly unlikely, and maglev railcars can be built wider than conventional railcars, offering more options for using the interior space and making them more comfortable to ride in. Maglevs produce little to no air pollution during operation, because no fuel is being burned, and the absence of friction makes the trains very quiet (both within and outside the cars) and provides a very smooth ride for passengers. Finally, maglev systems can operate on higher ascending grades (up to 10 percent) than traditional railroads (limited to about 4 percent or less), reducing the need to excavate tunnels or level the landscape to accommodate the tracks.

The greatest obstacle to the development of maglev systems is that they require entirely new infrastructure that cannot be integrated with existing railroads and that would also compete with existing highways, railroads, and air routes. Besides the costs of construction, one factor to be considered in developing maglev rail systems is that they require the use of rare-earth elements (scandium, yttrium, and 15 lanthanides), which may be quite expensive to recover and refine. Magnets made from rare-earth elements, however, produce a stronger magnetic field than ferrite (iron compounds) or alnico (alloys of iron, aluminum, nickel, cobalt, and copper) magnets to lift and guide the train cars over a guideway.

Maglev systems

Several train systems using maglev have been developed over the years, with most operating over relatively short distances. Between 1984 and 1995 the first commercial maglev system was developed in Great Britain as a shuttle between the Birmingham airport and a nearby rail station, some 600 meters (about 1,970 feet) away. Germany constructed a maglev in Berlin (the M-Bahn) that began operation in 1991 to overcome a gap in the city’s public transportation system caused by the Berlin Wall; however, the M-Bahn was dismantled in 1992, shortly after the wall was taken down. The 1986 World’s Fair (Expo 86) in Vancouver included a short section of a maglev system within the fairgrounds.

Six commercial maglev systems are currently in operation around the world. One is located in Japan, two in South Korea, and three in China. In Aichi, Japan, near Nagoya, a system built for the 2005 World’s Fair, the Linimo, is still in operation. It is about 9 km (5.6 miles) long, with nine station stops over that distance, and reaches speeds of about 100 km (62 miles) per hour. The Korean Rotem Maglev runs in the city of Taejeŏn between the Taejeŏn Expo Park and the National Science Museum, a distance of 1 km (0.6 mile). The Inch’ŏn Airport Maglev has six stations and runs from Inch’ŏn International Airport to the Yongyu station, 6.1 km (3.8 miles) away. The longest commercial maglev system is in Shanghai; it covers about 30 km (18.6 miles) and runs from downtown Shanghai to Pudong International Airport. The line is the first high-speed commercial maglev, operating at a maximum speed of 430 km (267 miles) per hour. China also has two low-speed maglev system operating at speeds of 100 km (62 miles) per hour. The Changsha Maglev connects that city’s airport to a station 18.5 km (11.5 miles) away, and the S1 line of the Beijing subway system has seven stops over a distance of 9 km (6 miles).

Japan has plans to create a long-distance high-speed maglev system, the Chuo Shinkansen, which would connect Nagoya to Tokyo, a distance of 286 km (178 miles), with an extension to Osaka (438 km [272 miles] from Tokyo) planned for 2037. However, the project was delayed past its original deadline in 2027 when the governor of Shizuoka Prefecture opposed the geological survey necessary to accommodate the high-speed train, citing impacts on biodiversity and water supply (though many surmised that it was because Shizuoka was the one prefecture with no station on the line). The governor’s resignation in 2024 effectively resumed the project, with new estimates placing the Nagoya-Tokyo line’s completion in 2034. The Chuo Shinkansen is planned to travel at 500 km (310 miles) per hour and make the Tokyo-Osaka trip in 67 minutes.

Details

Maglev (derived from magnetic levitation) is a system of rail transport whose rolling stock is levitated by electromagnets rather than rolled on wheels, eliminating rolling resistance.

Compared to conventional railways, maglev trains have higher top speeds, superior acceleration and deceleration, lower maintenance costs, improved gradient handling, and lower noise. However, they are more expensive to build, cannot use existing infrastructure, and use more energy at high speeds.

Maglev trains have set several speed records. The train speed record of 603 km/h (375 mph) was set by the experimental Japanese L0 Series maglev in 2015. From 2002 until 2021, the record for the highest operational speed of a passenger train of 431 kilometres per hour (268 mph) was held by the Shanghai maglev train, which uses German Transrapid technology. The service connects Shanghai Pudong International Airport and the outskirts of central Pudong, Shanghai. At its historical top speed, it covered the distance of 30.5 kilometres (19 mi) in just over 8 minutes (average speed: 228.75 km/h).

Different maglev systems achieve levitation in different ways, which broadly fall into two categories: electromagnetic suspension (EMS) and electrodynamic suspension (EDS). Propulsion is typically provided by a linear motor. The power needed for levitation is typically not a large percentage of the overall energy consumption of a high-speed maglev system. Instead, overcoming drag takes the most energy. Vactrain technology has been proposed as a means to overcome this limitation.

Despite over a century of research and development, there are only seven operational maglev trains today — four in China, two in South Korea, and one in Japan.

Two inter-city maglev lines are currently under construction, the Chūō Shinkansen connecting Tokyo and Nagoya (with further connection to Osaka) and a line between Changsha and Liuyang in Hunan Province, China.

Additional Information

The evolution of mass transportation has fundamentally shifted human civilization. In the 1860s, a transcontinental railroad turned the months-long slog across America into a week-long journey. Just a few decades later, passenger automobiles made it possible to bounce across the countryside much faster than on horseback. And of course, during the World War I era, the first commercial flights began transforming our travels all over again, making coast-to-coast journeys a matter of hours. But rail trips in the U.S. aren't much faster today than they were a century ago. For engineers looking for the next big breakthrough, perhaps "magical" floating trains are just the ticket.

In the 21st century there are a few countries using powerful electromagnets to develop high-speed trains, called maglev trains. These trains float over guideways using the basic principles of magnets to replace the old steel wheel and track trains. There's no rail friction to speak of, meaning these trains can hit speeds of hundreds of miles per hour.

Yet high speed is just one major benefit of maglev trains. Because the trains rarely (if ever) touch the track, there's far less noise and vibration than typical, earth-shaking trains. Less vibration and friction results in fewer mechanical breakdowns, meaning that maglev trains are less likely to encounter weather-related delays.

The first patents for magnetic levitation (maglev) technologies were filed by French-born American engineer Emile Bachelet all the way back in the early 1910s. Even before that, in 1904, American professor and inventor Robert Goddard had written a paper outlining the idea of maglev levitation [source: Witschge]. It wasn't long before engineers began planning train systems based on this futuristic vision. Soon, they believed, passengers would board magnetically propelled cars and zip from place to place at high speed, and without many of the maintenance and safety concerns of traditional railroads.

The big difference between a maglev train and a conventional train is that maglev trains do not have an engine — at least not the kind of engine used to pull typical train cars along steel tracks. The engine for maglev trains is rather inconspicuous. Instead of using fossil fuels, the magnetic field created by the electrified coils in the guideway walls and the track combine to propel the train.

If you've ever played with magnets, you know that opposite poles attract and like poles repel each other. This is the basic principle behind electromagnetic propulsion. Electromagnets are similar to other magnets in that they attract metal objects, but the magnetic pull is temporary. You can easily create a small electromagnet yourself by connecting the ends of a copper wire to the positive and negative ends of an AA, C or D-cell battery. This creates a small magnetic field. If you disconnect either end of the wire from the battery, the magnetic field is taken away.

The magnetic field created in this wire-and-battery experiment is the simple idea behind a maglev train rail system. There are three components to this system:

* A large electrical power source

* Metal coils lining a guideway or track

* Large guidance magnets attached to the underside of the train.

#3 This is Cool » Peregrine Falcon » Today 17:08:07

- Jai Ganesh

- Replies: 0

Peregrine Falcon

Gist

As swift as a speeding arrow and more rapid than a cheetah, the peregrine falcon is the fastest member of the animal kingdom, with a diving speed of more than 200 miles per hour.

The Peregrine Falcon (Falco peregrinus) is the fastest bird, and indeed the fastest animal, in the world, reaching incredible speeds of over 320 km/h (200 mph) during its hunting dive, known as a stoop, with some recorded at nearly 390 km/h (242 mph). Its aerodynamic body and specialized nostrils allow it to achieve these speeds to catch prey mid-air.

Summary

Powerful and fast-flying, the Peregrine Falcon hunts medium-sized birds, dropping down on them from high above in a spectacular stoop. They were virtually eradicated from eastern North America by pesticide poisoning in the middle 20th century. After significant recovery efforts, Peregrine Falcons have made an incredible rebound and are now regularly seen in many large cities and coastal areas.

Cool Facts:

* People have trained falcons for hunting for over a thousand years, and the Peregrine Falcon was always one of the most prized birds. Efforts to breed the Peregrine in captivity and reestablish populations depleted during the DDT years were greatly assisted by the existence of methods of handling captive falcons developed by falconers.

* The Peregrine Falcon is a very fast flier, averaging 40-55 km/h (25-34 mph) in traveling flight, and reaching speeds up to 112 km/h (69 mph) in direct pursuit of prey. During its spectacular hunting stoop from heights of over 1 km (0.62 mi), the peregrine may reach speeds of 320 km/h (200 mph) as it drops toward its prey.

* The Peregrine Falcon is one of the most widespread birds in the world. It is found on all continents except Antarctica, and on many oceanic islands.

* The oldest recorded Peregrine Falcon was at least 19 years, 9 months old, when it was identified by its band in Minnesota in 2012, the same state where it had been banded in 1992.

Details

The peregrine falcon (Falco peregrinus), also referred to simply as the peregrine, is a bird of prey (raptor) in the family Falconidae known for its speed. A large, crow-sized falcon, it has a blue-grey back, barred white underparts and a black head. As is typical for bird-eating (avivore) raptors, peregrine falcons are sexually dimorphic, with females being considerably larger than males. Historically, the bird has also been known as the "black-cheeked falcon" in Australia, and the "duck hawk" in North America.

The breeding range includes land regions from the Arctic tundra to the tropics. It can be found nearly everywhere on Earth, except extreme polar regions, very high mountains, and most tropical rainforests. The only major ice-free landmass from which it is entirely absent is New Zealand. That makes it the world's most widespread raptor and one of the most widely found wild bird species. In fact, the only land-based bird species found over a larger geographic area, domestic and feral pigeons, owe their success to human-led introduction. Both are domesticated forms of the rock dove, and are a major prey species for peregrine populations. Due to their greater abundance in cities than most other birds, feral pigeons support many peregrine populations as a staple food source, especially in urban settings.

The peregrine is a highly successful example of urban wildlife in much of its range, taking advantage of tall buildings as nest sites, and an abundance of prey such as pigeons and ducks. Both the English and scientific names of the species mean "wandering falcon", referring to the migratory habits of many northern populations. A total of 18 or 19 regional subspecies are accepted, which vary in appearance. Disagreement existed in the past over whether the distinctive Barbary falcon was represented by two subspecies of Falco peregrinus or was a separate species, F. pelegrinoides, and several of the other subspecies were originally described as species. However, the difference in their appearance is very small, as is their genetic difference, being only about 0.6–0.8% genetically differentiated. That indicates the divergence is relatively recent, occurring during the Last Ice Age, and all major ornithological authorities now treat the Barbary falcon as a subspecies.

Although its diet consists almost exclusively of medium-sized birds, the peregrine will sometimes hunt small mammals, small reptiles, or even insects. Reaching sexual maturity at one year, it mates for life and nests in a scrape, normally on cliff edges or, in recent times, on tall human-made structures. The peregrine falcon became an endangered species in many areas because of the widespread use of various pesticides, especially DDT. Since the ban on DDT from the early 1970s, populations have recovered, supported by large-scale protection of nesting places and releases to the wild.

The peregrine falcon is a well-respected falconry bird due to its strong hunting ability, high trainability, versatility, and availability via captive breeding. It is effective on most game bird species, from small to large. It has also been used as a religious, royal, or national symbol across many eras and civilizations.

Description

The peregrine falcon has a body length of 34 to 58 cm (13–23 in) and a wingspan from 74 to 120 cm (29–47 in). The male and female have similar markings and plumage but, as with many birds of prey, the peregrine falcon displays marked sexual dimorphism in size, with the female measuring up to 30% larger than the male. Males weigh 330 to 1,000 g (12–35 oz) and the noticeably larger females weigh 700 to 1,500 g (25–53 oz). In most subspecies, males weigh less than 700 g (25 oz) and females weigh more than 800 g (28 oz), and cases of females weighing about 50% more than their male breeding mates are not uncommon. The standard linear measurements of peregrines are: the wing chord measures 26.5 to 39 cm (10.4–15.4 in), the tail measures 13 to 19 cm (5.1–7.5 in) and the tarsus measures 4.5 to 5.6 cm (1.8–2.2 in).

The back and the long pointed wings of the adult are usually bluish black to slate grey with indistinct darker barring; the wingtips are black. The white to rusty underparts are barred with thin clean bands of dark brown or black. The tail, coloured like the back but with thin clean bars, is long, narrow, and rounded at the end with a black tip and a white band at the very end. The top of the head and a "moustache" along the cheeks are black, contrasting sharply with the pale sides of the neck and white throat. The cere is yellow, as are the feet, and the beak and claws are black. The upper beak is notched near the tip, an adaptation which enables falcons to kill prey by severing the spinal column at the neck. An immature bird is much browner, with streaked, rather than barred, underparts, and has a pale bluish cere and orbital ring.

The patch of black feathers below the falcon's eyes is called the malar stripe. A 2021 study of photos from around the world showed that the malar stripe is larger in areas that receive more sunlight, and concluded that the stripe serves to improve the falcon's vision by reducing glare.

Additional Information

Peregrine falcon, (Falco peregrinus) is the most widely distributed species of bird of prey, with breeding populations on every continent except Antarctica and many oceanic islands. Sixteen subspecies are recognized. The peregrine falcon is best known for its diving speed during flight—which can reach more than 300 km (186 miles) per hour—making it not only the world’s fastest bird but also the world’s fastest animal.

Coloration is a bluish gray above, with black bars on the white to yellowish white underparts. Adult peregrines range from about 36 to 49 cm (14.2 to 19.3 inches) in length. Strong and fast, they hunt by flying high and then diving at their prey. Attaining tremendous speeds of more than 320 km (200 miles) per hour, they strike with clenched talons and kill by impact. Their prey includes ducks and a wide variety of songbirds and shorebirds. Peregrines inhabit rocky open country near water where birds are plentiful. The usual nest is a mere scrape on a ledge high on a cliff, but a few populations use city skyscrapers or tree nests built by other bird species. The clutch is three or four reddish brown eggs, and incubation lasts about a month. The young fledge in five to six weeks.

Captive peregrine falcons have long been used in the sport of falconry. After World War II the peregrine falcon suffered a precipitous population decline throughout most of its global range. In most regions, including North America, the chief cause of the decline was traced to the pesticide DDT, which the birds had obtained from their avian prey. The chemical had become concentrated in the peregrine’s tissues and interfered with the deposition of calcium in the eggshells, causing them to be abnormally thin and prone to breakage. In the British Isles, direct mortality from another pesticide, dieldrin, was the most important cause of the decline. Following the banning or great reduction in the use of most organochlorine pesticides, populations have rebounded in virtually every part of the world and now exceed historical levels in many regions.

The American peregrine falcon (F. peregrinus anatum), which once bred from Hudson Bay to the southern United States, was formerly an endangered species. It had completely vanished from the eastern United States and eastern boreal Canada by the late 1960s. After Canada had banned DDT use by 1969 and the United States by 1972, vigorous captive breeding and reintroduction programs were initiated in both countries. Over the next 30 years, more than 6,000 captive progeny were released to the wild. North American populations recovered completely, and since 1999 the peregrine has not been listed as endangered. The peregrine has been listed as a species of least concern by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) since 2015.

#4 Science HQ » Tonsils » Today 16:37:20

- Jai Ganesh

- Replies: 0

Tonsils

Gist

Tonsils are two oval-shaped, immune-system tissue pads located at the back of the throat that act as a first line of defense against ingested or inhaled pathogens. They commonly become inflamed (tonsillitis) due to viruses or bacteria, causing sore throat, swelling, and difficulty swallowing. Treatments include antibiotics for bacterial infections, rest, and sometimes surgical removal (tonsillectomy).

Causes of tonsil issues (tonsillitis) are primarily viral or bacterial infections, like the cold, flu, or strep throat, but can also involve tonsil stones (tonsilloliths) from trapped debris, or more rarely, tonsil cancer, linked to HPV, tobacco, and alcohol. Tonsils, as part of the immune system, often get inflamed fighting germs, especially in children, leading to symptoms like sore throat, fever, and difficulty swallowing.

(HPV: human papillomavirus)

Summary

The tonsils are a set of lymphoid organs facing into the aerodigestive tract, which is known as Waldeyer's tonsillar ring and consists of the adenoid tonsil (or pharyngeal tonsil), two tubal tonsils, two palatine tonsils, and the lingual tonsils. These organs play an important role in the immune system.

When used unqualified, the term most commonly refers specifically to the palatine tonsils, which are two lymphoid organs situated at either side of the back of the human throat. The palatine tonsils and the adenoid tonsil are organs consisting of lymphoepithelial tissue located near the oropharynx and nasopharynx (parts of the throat).

Function

Tonsils are key components of the immune system, acting as the body's first line of defense against inhaled or ingested pathogens. Located at the entrance of the respiratory and digestive tracts, they monitor and respond to microbes by initiating immune responses. The tonsils contain a dense network of immune cells including B lymphocytes, T lymphocytes, macrophages, and dendritic cells. These cells interact within specialized regions called germinal centers, which become especially active during infections. Within these centers, B cells undergo activation, class switching (changing the type of antibody they produce), and somatic hypermutation of their antibody genes to better recognize and neutralize pathogens. Tonsils have a unique lymphoepithelial structure, with immune cells embedded within epithelial tissue, creating a direct interface with the external environment. This architecture facilitates efficient sampling of incoming bacteria and viruses through specialized M cells in the epithelium. The crypts in palatine tonsils significantly increase the surface area for antigen sampling, enhancing immune surveillance. The tonsillar immune response produces various antibodies—particularly immunoglobulins like IgA, IgG, and IgM—which contribute to both local and systemic immunity. Secretory IgA is especially important as it provides mucosal protection against pathogens before they can establish infection. In essence, the tonsils serve as immune surveillance stations, training grounds for antibody-producing cells, and barriers against infection at the body's entry points.

Details

Your tonsils, located in the back of your throat, are part of your immune system. They help fight infection and disease. Sometimes, you can develop issues with your tonsils, such as pain, swelling and infection. If these issues are chronic, your healthcare provider might recommend a tonsillectomy (tonsil removal).

Overview:

What are tonsils?

Your tonsils are two round, fleshy masses in the back of your throat (pharynx). Part of your immune system, your tonsils are like lymph nodes. They help filter out germs that enter through your nose or mouth to protect the rest of your body from infection. Tonsils are also called palatine tonsils or faucial tonsils.

Sometimes tonsils can become red, swollen or infected. If this issue becomes chronic or doesn’t get better, your healthcare provider might recommend a tonsillectomy (tonsil removal). Typically, people who have their tonsils removed can still fight off infection without any problems. Your body can find other ways to combat germs.

Function:

What’s the purpose of tonsils?

The main function of tonsils is fighting infection. Your tonsils contain a lot of white blood cells, which help kill germs. As your tonsils are in the back of your throat, they can “catch” germs that enter your body through your nose or mouth.

Anatomy:

Where are your tonsils?

Your tonsils are near the back of your throat, just behind your soft palate. There are two of them — one on each side.

What do my tonsils look like?

If you still have your tonsils, you can see them when you open your mouth wide and look in the mirror. They’re oval-shaped, pinkish mounds of tissue located on each side of your throat.

What color are my tonsils?

Healthy, normal tonsils are pinkish in color. But your tonsils can appear red and swollen if they’re inflamed or infected.

How big are the average tonsils?

Tonsil size varies significantly from person to person. But based on one research study:

* The average overall tonsil size is 42.81 cubic centimeters (cu cm).

* The average tonsil size in women is 37.65 {cm}^{3}.

* The average tonsil size in men is 52.4 {cm}^{3}.

To put this into perspective, each of your tonsils is slightly larger than a marshmallow.

Conditions and Disorders:

What are some conditions that affect tonsils?

There are a few different conditions that can affect your tonsils. The most common is tonsillitis — an infection of the tonsils. Bacteria and viruses can cause tonsillitis, and the infection can be short-term (acute) or long-term (chronic). The most common tonsillitis symptoms include a sore throat and swollen tonsils.

Other conditions that can affect your tonsils include:

* Strep throat. Caused by a bacterium known as Streptococcus, strep throat can cause sore throat, neck pain and fever.

* Tonsil stones. Also called tonsilloliths, tonsil stones are small white or yellow lumps in your tonsils. They can lead to tonsil pain, bad breath or bad taste.

* Peritonsillar abscess. A pocket of infection that pushes your tonsil to the other side of your throat, a peritonsillar abscess can cause difficulty swallowing or breathing. (If this happens, contact your healthcare provider immediately. Prompt treatment is essential.)

* Mononucleosis. Caused by a herpes virus called Epstein-Barr, mononucleosis can result in swollen tonsils, sore throat, fatigue and skin rash.

* Enlarged (hypertrophic) tonsils. Larger-than-normal tonsils can block your airway, leading to snoring or sleep apnea.

* Tonsil cancer. The most common form of oropharyngeal cancer, tonsil cancer is often linked to the human papillomavirus (HPV). Symptoms include tonsil pain, a lump in your neck and blood in your saliva (spit).

Are there tests to check the health of my tonsils?

Yes. If your healthcare provider suspects an issue with your tonsils, they may recommend:

* A bacterial culture test. Your provider rubs a cotton swab on your throat and tonsils. Then, they send the sample to a lab for analysis. A throat culture can check for different bacterial infections, including tonsillitis, strep throat and pneumonia.

* Blood tests. If your provider thinks your tonsil pain is due to mononucleosis, they can request a monospot test. This blood test detects certain antibodies, which can help confirm your diagnosis. (If the monospot test comes back negative, they can check for Epstein-Barr antibodies in your blood. This can also help determine whether you have mononucleosis.)

Additional Information

The tonsils are part of the body’s immune system. Because of their location at the throat and palate, they can stop germs entering the body through the mouth or the nose. The tonsils also contain a lot of white blood cells, which are responsible for killing germs.

There are different types of tonsils:

* Palatine tonsils (tonsilla palatina)

* The adenoids (pharyngeal tonsil or tonsilla pharyngealis)

* Lingual tonsil (tonsilla lingualis)

The two palatine tonsils are found on the right and left of the back of the throat, and are the only tonsils that can be seen unaided when you open your mouth. The adenoids are found high up in the throat, behind the nose, and can only be seen through rhinoscopy (an examination of the inside of the nose). The lingual tonsil is located far back at the base of the tongue, on its back surface.

All of these tonsillar structures together are sometimes called Waldeyer's ring since they form a ring around the opening to the throat from the mouth and nose. This position allows them to prevent germs like viruses or bacteria from entering the body through the mouth or the nose. There are also more immune system cells located behind Waldeyer's ring on the sides of the throat. These cells can take on the function of the adenoids if they have been removed.

The palatine tonsils can become inflamed. Known as tonsillitis, this makes them swell up and turn very red. They often have yellowish spots on them as well. The most common symptoms are a sore throat and fever.

The palatine tonsils and the adenoids may become enlarged, especially in children. That makes it harder to breathe and causes sleep problems. Because of these problems, tonsil surgery is sometimes recommended.

#5 Re: Jai Ganesh's Puzzles » General Quiz » Today 16:06:57

Hi,

#10761. What does the term in Geography Dam mean?

#10762. What does the term in Geography Dasymetric map mean?

#6 Re: Jai Ganesh's Puzzles » English language puzzles » Today 15:43:34

Hi,

#5957. What does the adjective gratifying mean?

#5958. What does the adjective au gratin mean?

#7 Re: Jai Ganesh's Puzzles » Doc, Doc! » Today 15:32:04

Hi,

#2575. What does the medical term Prostate cancer mean?

#8 Dark Discussions at Cafe Infinity » Come Quotes - XI » Today 15:26:03

- Jai Ganesh

- Replies: 0

Come Quotes - XI

1. You cannot mandate philanthropy. It has to come from within, and when it does, it is deeply satisfying. - Azim Premji

2. Liberty has never come from Government. Liberty has always come from the subjects of it. The history of liberty is a history of limitations of governmental power, not the increase of it. - Woodrow Wilson

3. This is my 20th year in the sport. I've known swimming and that's it. I don't want to swim past age 30; if I continue after this Olympics, and come back in 2016, I'll be 31. I'm looking forward to being able to see the other side of the fence. - Michael Phelps

4. For many, Christmas is also a time for coming together. But for others, service will come first. - Queen Elizabeth II

5. Gliders, sail planes, they're wonderful flying machines. It's the closest you can come to being a bird. - Neil Armstrong

6. Change will come slowly, across generations, because old beliefs die hard even when demonstrably false. - E. O. Wilson

7. I come from - I came from Wales, and it's a strong, butch society. We were in the war and all that. People didn't waste time feeling sorry for themselves. You had to get on with it. So my credo is get on with it. I don't waste time being soft. I'm not cold, but I don't like being, wasting my time with - life's too short. - Anthony Hopkins

8. Author: A fool who, not content with having bored those who have lived with him, insists on tormenting generations to come. - Montesquieu.

#9 Jokes » Ice cream Jokes - III » Today 15:13:53

- Jai Ganesh

- Replies: 0

Q: Why did the ice cream truck break down?

A: Because of the Rocky Road.

* * *

Q: How do you learn how to make ice cream?

A: In Sunday (Sundae) School.

* * *

Q: What happened when rockers couldn't get their favorite dessert?

A: Rage against the Broken Ice Cream Machine.

* * *

Who's there?

Ice cream!

Ice cream who?

Ice cream if you throw me in the cold, cold water!

* * *

There are two types of people in this world: People who love ice cream and liars.

* * *

#10 Re: Jai Ganesh's Puzzles » 10 second questions » Today 14:51:08

Hi,

#9861.

#11 Re: Jai Ganesh's Puzzles » Oral puzzles » Today 14:37:51

Hi,

#6355.

#12 Re: Exercises » Compute the solution: » Today 14:26:39

Hi,

2715.

#13 Re: Jai Ganesh's Puzzles » General Quiz » Today 00:33:51

Hi,

#10759. What does the term in Geography Cyclopean stairs mean?

#10760. What does the term in Geography Dale (landform) mean?

#14 Re: Jai Ganesh's Puzzles » English language puzzles » Today 00:21:48

Hi,

#5955. What does the noun dereliction mean?

#5956. What does the verd (used with object) derive mean?

#15 Re: Jai Ganesh's Puzzles » Doc, Doc! » Today 00:09:02

Hi,

#2574. What does the medical term Diphyllobothriasis mean?

#16 Dark Discussions at Cafe Infinity » Come Jokes - X » Today 00:00:29

- Jai Ganesh

- Replies: 0

Come Jokes - X

1. The American People will come first once again. My plan will begin with safety at home - which means safe neighborhoods, secure borders, and protection from terrorism. There can be no prosperity without law and order. - Donald Trump

2. I don't give up. I'm a plodder. People come and go, but I stay the course. - Kevin Costner

3. I don't believe in pessimism. If something doesn't come up the way you want, forge ahead. If you think it's going to rain, it will. - Clint Eastwood

4. If you come to fame not understanding who you are, it will define who you are. - Oprah Winfrey

5. Change is never easy, and it often creates discord, but when people come together for the good of humanity and the Earth, we can accomplish great things. - David Suzuki

6. There is only one difference between a long life and a good dinner: that, in the dinner, the sweets come last. - Robert Louis Stevenson

7. I would like to tell the young men and women before me not to lose hope and courage. Success can only come to you by courageous devotion to the task lying in front of you. - C. V. Raman

8. I'm most comfortable with the Southern dialects, really. It's easy, for example, for me to do Irish because we've got Irish heritage where I come from. - Brad Pitt.

#17 Jokes » Ice cream Jokes - II » Yesterday 23:24:42

- Jai Ganesh

- Replies: 0

Q: When does Oliver Stone eat ice cream?

A: Any Given Sundae.

* * *

Q: Where is the best place to get an ice cream?

A: IN A SUNDAY SCHOOL.

* * *

Q: What do you call a rapper working at Cold Stone?

A: Scoop Dogg.

* * *

Q: What do you call a metalhead working at Cold Stone?

A: Alice Scooper.

* * *

Q: What did the newspaper say to the ice cream?

A: What's the scoop?

* * *

#18 Re: Jai Ganesh's Puzzles » 10 second questions » Yesterday 23:08:32

Hi,

#9860.

#19 Re: Jai Ganesh's Puzzles » Oral puzzles » Yesterday 22:56:16

Hi,

#6354.

#20 Re: Exercises » Compute the solution: » Yesterday 22:19:46

Hi,

2714.

#21 This is Cool » Tower Bridge, London » Yesterday 18:24:25

- Jai Ganesh

- Replies: 0

Tower Bridge

Gist

The modern concrete and steel structure we know today was opened to traffic in 1973. Tower Bridge, on the other hand, has never fallen down. It stands today as it was built in 1894. It is known as London's defining landmark - representing London as an iconic structure that is recognised the world-over.

Tower Bridge is one of the most iconic London attractions and it's also very easy to visit. You can walk across the bridge for free or for a slight fee you can walk up inside the bridge, take in the breathtaking skyline and walk across the glass bottom walkway.

Summary

Tower Bridge is a movable bridge of the double-leaf bascule (drawbridge) type that spans the River Thames between the Greater London boroughs of Tower Hamlets and Southwark. It is a distinct landmark that aesthetically complements the Tower of London, which it adjoins.

The bridge was completed in 1894. It is about 240 meters (800 feet) in length and provides an opening 76 meters (250 feet) wide. Its twin towers rise 61 meters (200 feet) above the Thames. Between the towers stretch a pair of glass-covered walkways that are popular among tourists. The walkways were originally designed to allow pedestrians to cross even while the bridge was raised, but they became hangouts for sex workers and thieves and so were closed from 1909 to 1982.

The Tower Bridge was operated by hydraulic pumps driven by steam until 1976, when electric motors were put into operation; the steam power system is still kept (in good repair) as a tourist display. Because of the reduction in shipping at the London Docklands, however, the leaves are raised less frequently. The modern bridge raises the leaves about 800 times a year, down from more than 6,000 times a year in 1894.

Details

Tower Bridge is a Grade I listed combined bascule, suspension, and, until 1960, cantilever bridge in London, built between 1886 and 1894, designed by Horace Jones and engineered by John Wolfe Barry with the help of Henry Marc Brunel. It crosses the River Thames close to the Tower of London and is one of five London bridges owned and maintained by the City Bridge Foundation, a charitable trust founded in 1282.

The bridge was constructed to connect the 39% of London's population that lived east of London Bridge, equivalent to the populations of "Manchester on the one side, and Liverpool on the other", while allowing shipping to access the Pool of London between the Tower of London and London Bridge. The bridge was opened by Edward, Prince of Wales, and Alexandra, Princess of Wales, on 30 June 1894.

The bridge is 940 feet (290 m) in length including the abutments and consists of two 213-foot (65 m) bridge towers connected at the upper level by two horizontal walkways, and a central pair of bascules that can open to allow shipping. Originally hydraulically powered, the operating mechanism was converted to an electro-hydraulic system in 1972. The bridge is part of the London Inner Ring Road and thus the boundary of the London congestion charge zone, and remains an important traffic route with 40,000 crossings every day. The bridge deck is freely accessible to both vehicles and pedestrians, whereas the bridge's twin towers, high-level walkways, and Victorian engine rooms form part of the Tower Bridge Exhibition.

Tower Bridge has become a recognisable London landmark. It is sometimes confused with London Bridge, about 0.5 miles (800 m) upstream, which has led to a persistent urban legend about an American purchasing the wrong bridge.

Touring the bridge

The Tower Bridge attraction is a display housed inside the bridge's towers, the high-level walkways, and the Victorian engine rooms. It uses films, photos, and interactive displays to explain why and how Tower Bridge was built. Visitors can access the original steam engines that once powered the bridge bascules, housed in Engine Rooms, underneath the south end of the bridge.

The attraction charges an admission fee. The entrance is from the ticket office on the west side of the North Tower, from where visitors can climb the stairs (or take a lift) to the high-level Walkways to cross to the South Tower. In the Towers and Walkways is interpretation about the history of the bridge. The Walkways also provide views over the city, the Tower of London and the Pool of London, and include two Glass Floors, where you can look down to see the road and River Thames below. From the South Tower, visitors can visit exit and follow the Blue Line to the Victorian Engine Rooms, with the original steam engines, which are situated in a separate building underneath the southern approach to the bridge.

Of the 1,114 English visitor attractions tracked by Visit England, in 2019 Tower Bridge had 889,338 visitors and was the 34th most visited attraction in England, and the 17th most visited attraction that charged an admission fee. It is one of only three bridges in England tracked as a visitor attraction alongside the Clifton Suspension Bridge in Bristol and The Iron Bridge in Shropshire.

Additional Information

Opened on 30 June 1894, Tower Bridge was built by and is owned and managed by the charity City Bridge Foundation - historically known as Bridge House Estates. It was founded around 900 years ago to maintain the old London Bridge, using income from bridge tolls, rents and bequests. Today, it owns and maintains Tower Bridge and London, Southwark, Millennium and Blackfriars bridges - at no cost to the taxpayer.

Tower Bridge was built to ease road traffic while maintaining river access to the busy Pool of London docks. Built with giant movable roadways that lift up for passing ships, it is to this day considered an engineering marvel and beyond being one of London’s favourite icons.

#22 Science HQ » Vertigo » Yesterday 17:57:45

- Jai Ganesh

- Replies: 0

Vertigo

Gist

Vertigo is a sensation of spinning, swaying, or tilting, usually caused by inner ear problems (peripheral) or brain issues (central). Common causes include BPPV, vestibular neuritis, and migraines. Symptoms include nausea, vomiting, sweating, and loss of balance, typically lasting from a few seconds to several days. (BPPV: Benign Paroxysmal Positional Vertigo).

Is vertigo a permanent condition?

No, vertigo is not always permanent; it depends on the underlying cause, with many cases being temporary, curable with specific maneuvers like for BPPV, or manageable with treatment, though some conditions like Ménière's disease can cause recurring or chronic episodes. Proper diagnosis is key, as treatments range from simple repositioning exercises to medications or therapies, often resolving symptoms or significantly reducing their impact.

Summary

Vertigo is a sensation of feeling off balance. If you have these dizzy spells, you might feel like you are spinning or that the world around you is spinning.

Vertigo is a sensation that you or the world around you is spinning. It's usually a symptom of a problem with the part of your inner ear or brain that keeps you balanced. Treating a connected health issue may help to relieve vertigo.

Vertigo Causes

Vertigo often happens because of an inner ear problem. Some of the most common causes include:

Benign paroxysmal positional vertigo (BPPV). This inner ear disorder happens when tiny calcium particles (canaliths) get dislodged from their normal location and collect in the inner ear. The inner ear sends signals to the brain about your head and body movements to help you keep your balance.

BPPV can occur for no known reason and may worsen as you get older.

* Meniere's disease. This inner ear disorder may be caused by a buildup of fluid and changing pressure in the ear. It can cause episodes of vertigo along with ringing in the ears (tinnitus) and hearing loss.

* Vestibular neuritis or labyrinthitis. This inner ear problem is usually related to a viral infection such as chickenpox, measles, or hepatitis. The infection inflames nerves that help your brain keep you balanced.

Details

Vertigo causes dizziness and makes you feel like you’re spinning when you’re not. It most commonly occurs when there’s an issue with your inner ear. But you can also develop it if you have a condition affecting your brain, like a tumor or stroke. Treatments vary and can include medication, repositioning maneuvers or surgery.

Overview:

What is vertigo?

Vertigo is a sensation that the environment around you is spinning in circles. It can make you feel dizzy and off-balance. Vertigo is a symptom of lots of health conditions rather than a disease itself, but it can occur along with other symptoms.

Other symptoms you might experience when you have vertigo include:

* Nausea and vomiting.

* Dizziness.

* Balance issues.

* Hearing loss in one or both ears.

* Tinnitus (ringing in your ears).

* Headaches.

* Motion sickness.

* A feeling of fullness in your ear.

* Nystagmus (a condition that causes your eyes to move from side to side rapidly and uncontrollably).

Types of vertigo

There are two main types of vertigo: peripheral and central.

* Peripheral vertigo is the most common type. It happens when there’s an issue with your inner ear or vestibular nerve. (Both help with your sense of balance.)

Subtypes of peripheral vertigo include:

** Benign paroxysmal positional vertigo (BPPV).

** Labyrinthitis.

** Vestibular neuritis.

** Ménière’s disease.

* Central vertigo is less common. It occurs when you have a condition affecting your brain, like an infection, stroke or traumatic brain injury. People with central vertigo usually have more severe symptoms like severe instability or difficulty walking.

Possible Causes:

What causes vertigo?

Vertigo causes vary from person to person and may include:

* Migraine headaches.

* Certain medications, including some antibiotics, anti-inflammatories and cardiovascular drugs.

* Stroke.

* Arrhythmia.

* Diabetes.

* Head injuries.

* Prolonged bed rest.

* Shingles in or near your ear.

* Ear surgery.

* Perilymphatic fistula (when inner ear fluid leaks into your middle ear).

* Hyperventilation (rapid breathing).

* Low blood pressure (your blood pressure decreases when you stand up).

* Ataxia (muscle weakness).

* Syphilis.

* Otosclerosis (a bone growth issue affecting your middle ear).

* Brain diseases.

* Multiple sclerosis (MS).

* Acoustic neuroma.

What are the possible complications of vertigo?

Vertigo can cause falls, which may result in bone fractures (broken bones) or other injuries. Vertigo can also interfere with your quality of life and hinder your ability to drive or go to work.

Care and Treatment:

How do healthcare providers diagnose vertigo?

A healthcare provider will perform a physical exam and ask questions about your vertigo symptoms. They may also recommend one or more tests to confirm your diagnosis.

Vertigo diagnostic tests

Healthcare providers may perform some tests to diagnose vertigo. These tests can include:

* Fukuda-Unterberger test. Your healthcare provider will ask you to march in place for 30 seconds with your eyes closed. If you rotate or lean to one side, it could mean that you have an issue with your inner ear labyrinth. This could cause vertigo.

* Romberg’s test. During this assessment, your provider will ask you to close your eyes while standing with your feet together and your arms to your side. If you feel unbalanced or unsteady, it could mean that you have an issue with your central nervous system (your brain or spinal cord).

* Head impulse test. For this test, your provider will gently move your head to each side while you focus your eyes on a stationary target (for example a spot on the wall or your provider’s nose). As they move your head, they’ll pay close attention to your eye movements. This can tell them if there’s an issue with the balance system in your inner ear.

* Vestibular test battery. This includes several different tests to check the vestibular portion of your inner ear system. A vestibular test battery can help determine whether your symptoms are a result of an inner ear issue or a brain issue.

* Imaging tests: These may include CT (computed tomography) scans or MRI (magnetic resonance imaging).

How do healthcare providers treat vertigo?

Vertigo treatment depends on the underlying cause. Healthcare providers use a variety of treatments, which may include:

* Repositioning maneuvers.

* Vertigo medication.

* Vestibular rehabilitation therapy (vertigo exercises).

* Surgery.

Repositioning maneuvers

Benign paroxysmal positional vertigo (BPPV) occurs when tiny calcium carbonate crystals (canaliths) move out of the utricle in your inner ear (where they belong) into your semicircular canals. This can cause vertigo symptoms, especially when you change your head position.

Canalith repositioning procedures, like the Epley maneuver, can help shift the crystals out of your semicircular canals back into your utricle. These maneuvers consist of a series of specific head movements. A healthcare provider can perform a canalith repositioning procedure during an office visit. They can also teach you how to do it at home.

Vertigo medication

Medication may help in some cases of acute (sudden onset, short duration) vertigo. Healthcare providers may recommend motion sickness medications (like meclizine or dimenhydrinate) or antihistamines (like cyclizine) to ease vertigo symptoms.

Vestibular rehabilitation therapy (vertigo exercises)

Vestibular rehabilitation therapy usually involves a range of exercises to improve common vertigo symptoms like dizziness, unstable vision and balance issues. A healthcare provider will tailor your treatment according to your unique needs. Exercises may include stretching, strengthening, eye movement control and marching in place. Your provider can teach you how to do these exercises at home so you can manage your symptoms whenever you have a vertigo episode.

Surgery

It’s rare, but you might need surgery when a serious underlying health issue — like a brain tumor or neck injury — causes vertigo. Providers typically only recommend surgery when other treatments don’t work. Your provider or surgeon will tell you which type of procedure you need and what to expect.

How do you get vertigo to go away on its own?

It’s not always possible to get rid of vertigo without the help of a healthcare provider. But here are some things you can try at home to ease your symptoms:

* Move slowly when standing up, turning your head or performing other triggering movements.

* Sleep with your head elevated on two pillows.

* Lie in a dark, quiet room to reduce the spinning sensation.

* Sit down as soon as you feel dizzy.

* Squat down instead of bending over at the waist when picking something up.

* Turn on the lights if you get up during the night.

* Use a cane or walking stick if you feel like you might fall.

How to cure vertigo permanently

Unfortunately, there’s no surefire way to get rid of vertigo permanently and keep it from coming back. Some people have vertigo once and never have it again. Others experience recurring (returning) episodes.

If you have severe or frequent vertigo, talk to your healthcare provider about ways to manage your symptoms and improve your quality of life.

Additional Information

Vertigo is a symptom, rather than a condition itself. It’s the feeling that you, or the environment around you, is moving or spinning.

This feeling may be barely noticeable, or it may be so severe that you find it difficult to keep your balance and do everyday tasks.

Vertigo can develop suddenly and last for a few seconds or much longer. If you have severe vertigo, your symptoms may be constant and last for several days, making daily life very difficult.

Symptoms of vertigo may include:

* loss of balance – which can make it difficult to stand or walk

* feeling sick or being sick

* dizziness

When to get medical advice

Speak to your GP practice if:

* your vertigo comes on suddenly

* you have vertigo that will not go away

* you have vertigo that keeps coming back

* vertigo is affecting your daily life

Diagnosing vertigo

Your GP will ask about your symptoms and can carry out an examination to help determine some types of vertigo. They may also refer you for further tests.

What causes vertigo?

Inner ear problems, which affect balance, are the most common causes of vertigo. It can also be caused by problems in certain parts of the brain.

Common causes of vertigo may include:

* benign paroxysmal positional vertigo (BPPV) – where certain head movements trigger vertigo

* migraine

* labyrinthitis or vestibular neuronitis – an inner ear infection

* persistent postural-perceptual dizziness (PPPD)

* Ménière’s disease

Less commonly, vertigo can sometimes be caused by conditions that affect certain parts of the brain. This can include:

* a stroke

* multiple sclerosis

* brain tumours

Depending on the condition causing vertigo, you may have other symptoms, such as:

* a high temperature

* ringing in your ears (tinnitus)

* hearing loss

Treatment for vertigo

Treatment will depend on the cause. Gentle movement is encouraged as soon as you are able to. This will help the balance systems in your body reset.

Medicines (such as prochlorperazine and some antihistamines) may help in most cases of vertigo. These should only be used for a short amount of time (3-5 days). Long term use may slow the recovery process.

Many people with vertigo get better without treatment. If you’re still experiencing vertigo or balance problems after 6 weeks, you may be referred to a Vestibular (balance) Physiotherapist or an ENT (Ear, nose & throat) consultant.

#23 Science HQ » Galvanometer » 2026-02-20 23:41:35

- Jai Ganesh

- Replies: 0

Galvanometer

Gist

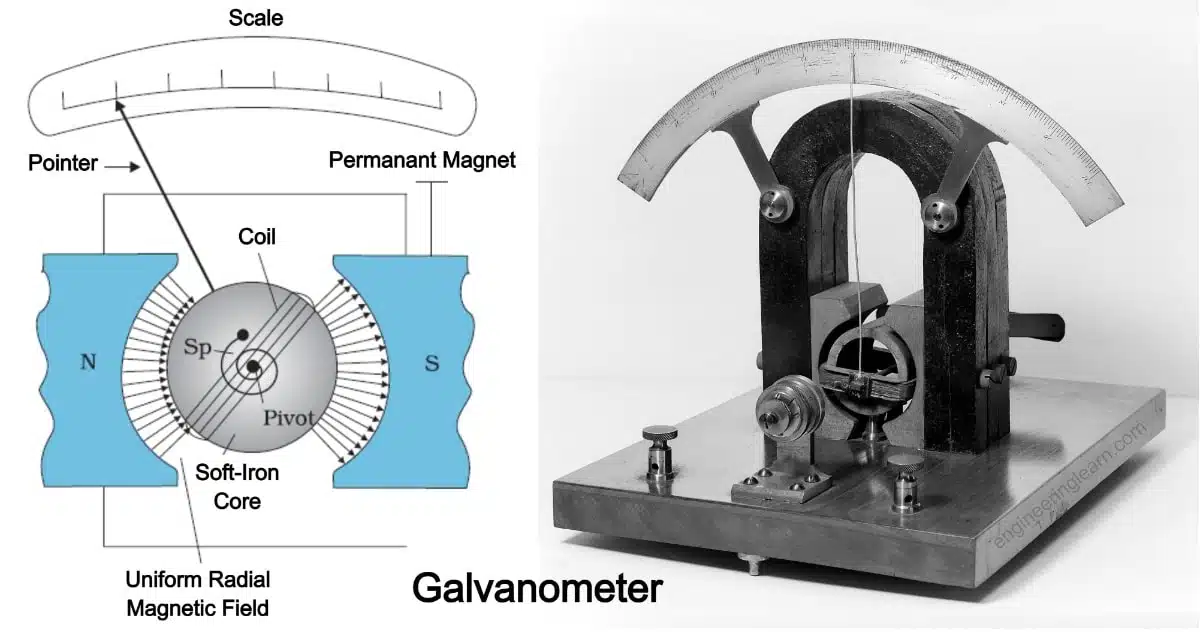

A galvanometer is a highly sensitive electromechanical instrument used to detect and measure small electric currents, primarily in DC circuits. It operates on the principle that a current-carrying coil placed in a magnetic field experiences a torque, causing a pointer to deflect across a scale proportional to the current.

A galvanometer is used to detect the presence, direction, and magnitude of small electric currents in a circuit, acting as a highly sensitive measuring instrument that shows current flow by deflecting a pointer or mirror, often serving as the core component in analog meters like ammeters and voltmeters.

Summary

Galvanometer is the historical name given to a moving coil electric current detector. When a current is passed through a coil in a magnetic field, the coil experiences a torque proportional to the current. If the coil's movement is opposed by a coil spring, then the amount of deflection of a needle attached to the coil may be proportional to the current passing through the coil. Such "meter movements" were at the heart of the moving coil meters such as voltmeters and ammeters until they were largely replaced with solid state meters.

The accuracy of moving coil meters is dependent upon having a uniform and constant magnetic field. The illustration shows one configuration of permanent magnet which was widely used in such meters.

Details

Galvanometers are instruments that measure the electrical potential difference between two points in an electric circuit. The word “galvanometer” comes from the Italian scientist Luigi Galvani, who discovered the principle of bioelectricity in the 18th century.

The earliest galvanometers were simple compasses that were used to detect the presence of an electric current. Over time, these devices became more sophisticated, incorporating coils of wire that could detect very small changes in the electrical current.

In the 19th century, the invention of the tangent galvanometer by William Thomson (later known as Lord Kelvin) revolutionized the field of electricity. This device used a magnet and a coil of wire to measure the strength and direction of an electric current. It was used to develop the first accurate measurements of electrical resistance and to study the behaviour of electric currents in different materials.

Today, galvanometers are used in a wide range of scientific and industrial applications, from measuring the electrical activity of the brain to detecting the presence of magnetic fields. They are also used in a variety of medical devices, such as electrocardiograms (ECGs) and electroencephalograms (EEGs).

The significance of these in modern science cannot be overstated. They have enabled scientists to make accurate measurements of electrical and magnetic fields, paving the way for advances in fields such as physics, chemistry, and engineering. They have also played a crucial role in developing new technologies that have transformed the way we live and work.

Additional Information

A galvanometer is an electromechanical measuring instrument for electric current. Early galvanometers were uncalibrated, but improved versions, called ammeters, were calibrated and could measure the flow of current more precisely. Galvanometers work by deflecting a pointer in response to an electric current flowing through a coil in a constant magnetic field. The mechanism is also used as an actuator in applications such as hard disks.

Galvanometers came from the observation, first noted by Hans Christian Ørsted in 1820, that a magnetic compass's needle deflects when near a wire having electric current. They were the first instruments used to detect and measure small amounts of current. André-Marie Ampère, who gave mathematical expression to Ørsted's discovery, named the instrument after the Italian electricity researcher Luigi Galvani, who in 1791 discovered the principle of the frog galvanoscope – that electric current would make the legs of a dead frog jerk.

Galvanometers have been essential for the development of science and technology in many fields. For example, in the 1800s they enabled long-range communication through submarine cables, such as the earliest transatlantic telegraph cables, and were essential to discovering the electrical activity of the heart and brain, by their fine measurements of current.

Galvanometers have also been used as the display components of other kinds of analog meters (e.g., light meters and VU meters), capturing the outputs of these meters' sensors. Today, the main type of galvanometer still in use is the D'Arsonval/Weston type.

Operation

Modern galvanometers, of the D'Arsonval/Weston type, are constructed with a small pivoting coil of wire, called a spindle, in the field of a permanent magnet. The coil is attached to a thin pointer that traverses a calibrated scale. A tiny torsion spring pulls the coil and pointer to the zero position.

When a direct current (DC) flows through the coil, the coil generates a magnetic field. This field acts against the permanent magnet. The coil twists, pushing against the spring, and moves the pointer. The hand points at a scale indicating the electric current. Careful design of the pole pieces ensures that the magnetic field is uniform so that the angular deflection of the pointer is proportional to the current. A useful meter generally contains a provision for damping the mechanical resonance of the moving coil and pointer, so that the pointer settles quickly to its position without oscillation.

The basic sensitivity of a meter might be, for instance, 100 microamperes full scale (with a voltage drop of, say, 50 millivolts at full current). Such meters are often calibrated to read some other quantity that can be converted to a current of that magnitude. The use of current dividers, often called shunts, allows a meter to be calibrated to measure larger currents. A meter can be calibrated as a DC voltmeter if the resistance of the coil is known by calculating the voltage required to generate a full-scale current. A meter can be configured to read other voltages by putting it in a voltage divider circuit. This is generally done by placing a resistor in series with the meter coil. A meter can be used to read resistance by placing it in series with a known voltage (a battery) and an adjustable resistor. In a preparatory step, the circuit is completed and the resistor adjusted to produce full-scale deflection. When an unknown resistor is placed in series in the circuit the current will be less than full scale and an appropriately calibrated scale can display the value of the previously unknown resistor.

These capabilities to translate different kinds of electric quantities into pointer movements make the galvanometer ideal for turning the output of other sensors that output electricity (in some form or another), into something that can be read by a human.

Because the pointer of the meter is usually a small distance above the scale of the meter, parallax error can occur when the operator attempts to read the scale line that "lines up" with the pointer. To counter this, some meters include a mirror along with the markings of the principal scale. The accuracy of the reading from a mirrored scale is improved by positioning one's head while reading the scale so that the pointer and the reflection of the pointer are aligned; at this point, the operator's eye must be directly above the pointer and any parallax error has been minimized.

Uses

Probably the largest use of galvanometers was of the D'Arsonval/Weston type used in analog meters in electronic equipment. Since the 1980s, galvanometer-type analog meter movements have been displaced by analog-to-digital converters (ADCs) for many uses. A digital panel meter (DPM) contains an ADC and numeric display. The advantages of a digital instrument are higher precision and accuracy, but factors such as power consumption or cost may still favor the application of analog meter movements.

Modern uses

Most modern uses for the galvanometer mechanism are in positioning and control systems. Galvanometer mechanisms are divided into moving magnet and moving coil galvanometers; in addition, they are divided into closed-loop and open-loop - or resonant - types.

Mirror galvanometer systems are used as beam positioning or beam steering elements in laser scanning systems. For example, for material processing with high-power lasers, closed loop mirror galvanometer mechanisms are used with servo control systems. These are typically high power galvanometers and the newest galvanometers designed for beam steering applications can have frequency responses over 10 kHz with appropriate servo technology. Closed-loop mirror galvanometers are also used in similar ways in stereolithography, laser sintering, laser engraving, laser beam welding, laser TVs, laser displays and in imaging applications such as retinal scanning with Optical Coherence Tomography (OCT) and Scanning Laser Ophthalmoscopy (SLO). Almost all of these galvanometers are of the moving magnet type. The closed loop is obtained measuring the position of the rotating axis with an infrared emitter and 2 photodiodes. This feedback is an analog signal.

Open loop, or resonant mirror galvanometers, are mainly used in some types of laser-based bar-code scanners, printing machines, imaging applications, military applications and space systems. Their non-lubricated bearings are especially of interest in applications that require functioning in a high vacuum.

A galvanometer mechanism (center part), used in an automatic exposure unit of an 8 mm film camera, together with a photoresistor (seen in the hole on top of the leftpart).

Moving coil type galvanometer mechanisms (called 'voice coils' by hard disk manufacturers) are used for controlling the head positioning servos in hard disk drives and CD/DVD players, in order to keep mass (and thus access times), as low as possible.

Past uses

A major early use for galvanometers was for finding faults in telecommunications cables. They were superseded in this application late in the 20th century by time-domain reflectometers.

Galvanometer mechanisms were also used to get readings from photoresistors in the metering mechanisms of film cameras.

In analog strip chart recorders such as used in electrocardiographs, electroencephalographs and polygraphs, galvanometer mechanisms were used to position the pen. Strip chart recorders with galvanometer driven pens may have a full-scale frequency response of 100 Hz and several centimeters of deflection.

#24 This is Cool » Bronchoscopy » 2026-02-20 23:07:41

- Jai Ganesh

- Replies: 0

Bronchoscopy

Gist

A bronchoscopy is a minimally invasive medical procedure used to examine, diagnose, and treat airway and lung conditions by inserting a thin, flexible tube (bronchoscope) with a light and camera through the nose or mouth. It is commonly used to investigate persistent coughs, infections, or abnormalities found on chest X-rays, such as tumors or foreign bodies.

What is the purpose of doing a bronchoscopy?

Common reasons for needing bronchoscopy are a persistent cough, infection or something unusual seen on a chest X-ray or other test. Bronchoscopy can also be used to obtain samples of mucus or tissue, to remove foreign bodies or other blockages from the airways or lungs, or to provide treatment for lung problems.

Summary

A bronchoscopy is an essential tool for clinicians and health care providers treating patients with lung diseases. Since its introduction to clinical practice by Shigeto Ikeda in 1966, flexible bronchoscopy has become an essential tool in diagnosis and management of patients with lung diseases. Rigid bronchoscopy can be particularly helpful in therapeutic cases. This activity describes the indications, contraindications of bronchoscopy and highlights the role of the interprofessional team in managing patients with airway disorders.

Introduction

A bronchoscopy is an essential tool for clinicians and health care providers treating patients with lung diseases. Since its introduction to clinical practice by Shigeto Ikeda in 1966, flexible bronchoscopy has become an essential tool in diagnosis and management of patients with lung diseases. Rigid bronchoscopy can be particularly helpful in therapeutic cases.

Anatomy and Physiology

A flexible bronchoscope, equipped with fiber optics, camera, and light source, allows for real-time, direct visualization of the airways. It can be used to examine the respiratory tract starting from the oral or nasal cavity to the sub-segmental bronchi. Advanced bronchoscopic techniques such as endobronchial ultrasound enable ultrasonographic evaluation of mediastinal structures such as lymph nodes, as well as the periphery of the lung.

Details

Bronchoscopy is a procedure to look directly at the airways in the lungs using a thin, lighted tube (bronchoscope). The bronchoscope is put in the nose or mouth. It is moved down the throat and windpipe (trachea), and into the airways. A healthcare provider can then see the voice box (larynx), trachea, and large and medium-sized airways.

There are 2 types of bronchoscopes: flexible and rigid. Both types come in different widths.

A rigid bronchoscope is a straight tube. It’s only used to view the larger airways. It may be used within the bronchi to:

* Remove a large amount of secretions or blood

* Control bleeding

* Remove foreign objects

* Remove diseased tissue (lesions)

* Do procedures, such as stents and other treatments

A flexible bronchoscope is used more often. Unlike the rigid scope, it can be moved down into the smaller airways (bronchioles). The flexible bronchoscope may be used to:

* Place a breathing tube in the airway to help give oxygen

* Suction out secretions

* Take tissue samples (biopsy)

* Put medicine into the lungs

Why might I need bronchoscopy?

A bronchoscopy may be done to diagnose and treat lung problems such as:

* Tumors or bronchial cancer

* Airway blockage (obstruction)

* Narrowed areas in airways (strictures)

* Inflammation and infections such as tuberculosis (TB), pneumonia, and fungal or parasitic lung infections

* Interstitial pulmonary disease

* Causes of persistent cough

* Causes of coughing up blood

* Spots seen on chest X-rays

* Vocal cord paralysis

Diagnostic procedures or treatments that are done with bronchoscopy include:

* Biopsy of tissue

* Collection of sputum

* Fluid put into the lungs and then removed (bronchoalveolar lavage or BAL) to diagnose lung disorders

* Removal of secretions, blood, mucus plugs, or growths (polyps) to clear airways

* Control of bleeding in the bronchi

* Removing foreign objects or other blockages

* Laser therapy or radiation treatment for bronchial tumors

* Placement of a small tube (stent) to keep an airway open (stent placement)

* Draining an area of pus (abscess)

Your healthcare provider may also have other reasons to advise a bronchoscopy.

What are the risks of bronchoscopy?

In most cases, the flexible bronchoscope is used, not the rigid bronchoscope. This is because the flexible type has less risk of damaging the tissue. And it provides better access to smaller areas of the lung tissue.

All procedures have some risks. The risks of this procedure may include:

* Bleeding

* Infection

* Hole in the airway (bronchial perforation)

* Irritation of the airways (bronchospasm)

* Irritation of the vocal cords (laryngospasm)